A couple of months ago a new acquaintance asked me, “Hey, do you remember Bruno Lawrence?” I had to smile, just mention the name and I smile.

Bruno Lawrence was a New Zealand superstar, with one of the most recognisable faces and one of the most recognisable voices in this country’s history – a superb drummer, session musician, songwriter and band leader, adept in jazz, funk, pop and rock, who went on to a formidable acting career. Billy Kristian, who might know, has called him ‘the best Tamla Motown-type drummer to come out of New Zealand”; Jack Nicholson cited him as one of his favourite actors. Bruno’s career has been well-documented. These words, written on the 20th anniversary of his passing, aren’t about Bruno Lawrence, actor and musician, but about our friendship . . .

BLERTA, 1973 with Bruno on the right and Fane Flaws in the centre - The Dominion Post collection. National Library of New Zealand

In the immediate years following Bruno’s death, there was a published biography and a television documentary, both disappointing; the book fails to capture the excitement of Bruno’s presence (“like living on the edge of a volcano,” Max Merritt described it) and the doco, in Veronica Lawrence’s words, portrayed her husband as “an obnoxious drunk and sexual predator”.

I shared Veronica’s umbrage. Bruno preyed on nobody and those brown eyes flirted with all, a magnetic presence, and it’s easy to portray an obnoxious drunk when the interviewees are tee-totallers and reformed alcoholics. I’ve heard some of those stories of poor behaviour, including a few from Veronica, but not on my shift and I don’t know why I was largely exempt.

You can read this memoir and conclude that my relationship with Bruno was purely as party companion but there were countless evenings just hanging out, at home or at Bruno’s motel during film shoots, quiet nights huddled around the wood-burner at Waimarama. One evening after dining in Mt Eden, we drove up Maungawhau before midnight and stayed for sunrise, chatting throughout the night. And those are some of my most precious memories of Bruno, intimate times I can’t share with my nearest and dearest, much less anonymous readers, and who would want to read them anyway?

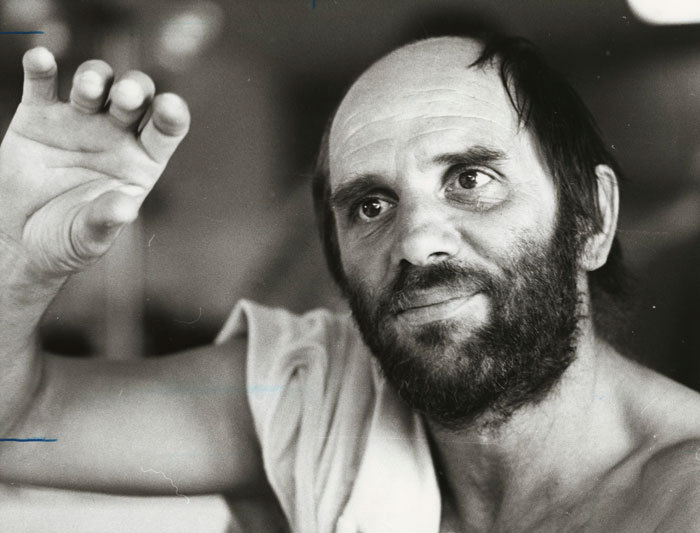

Bruno Lawrence, circa 1989 - Photo by Don Scott. National Library of New Zealand.

Bruno Lawrence was a hoon, make no mistake, and he would have been long-remembered as a “character” regardless of his occupation, but he was unique and inspirational. Fame was the price he paid for his achievements and he lived with it comfortably, always approachable, he’d talk to anyone, many fans became friends. I was a fan and I became a friend ...

I met Bruno in Sydney in the late-1960s, although we were little more than acquaintances until the mid-1970s. By then, 10 years my senior, he was a musical legend, if not the later national icon he was to become. He’d played with Claude Papesch, Ricky May and the mighty Max Merritt, and he was the leader of the generation-defining BLERTA. Between 1976 and 1981 I lived at Snoring Waters, the "BLERTA commune" at Waimarama, Hawke's Bay. My two children, Karenza and Dylan, were born at Hastings Hospital, Snoring Waters was their first home. Bruno and I had history and I call him my mate as casually as my kids refer to him as Uncle Bruno.

Going out for a coffee with Bruno could lead to all sorts of adventures. I travelled the length and breadth of Aotearoa with Bruno. We spent a whole day in Lawrence, Central Otago, “because it was there” and attended the Bay of Islands Jazz Festival without a change of clothes and stayed a week. We once took five days to cover the six-hour drive from Auckland to Waimarama. When the BLERTA bus took sick in southern Hawke's Bay, requiring parts to be delivered, we pub-crawled the rohe, spending a day apiece in Norsewood, Dannevirke and Woodville. On another occasion the bus, filled with kids, broke down on the Pahiatua Track. We didn’t see a vehicle for two hours so a young Matt Murphy and I walked and hitched to Palmerston North for assistance.

When Bruno received a development grant for his proposed directorial debut, Blowing It, he hauled me in as “advisor” to check out bands around the country. In turn, when Stranded In Paradise was released, Bruno was my companion for the book’s promo tour. We saw a lot of our great country together.

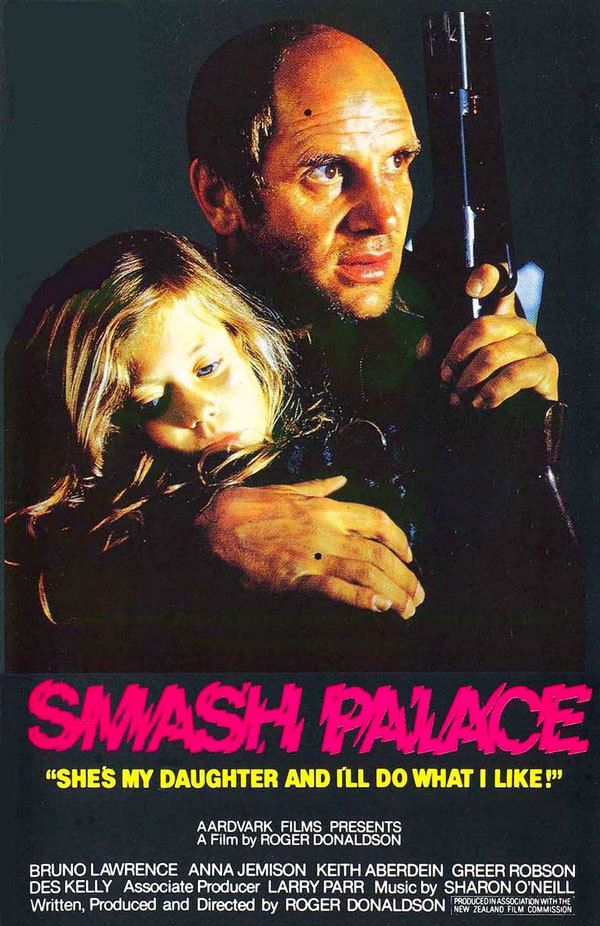

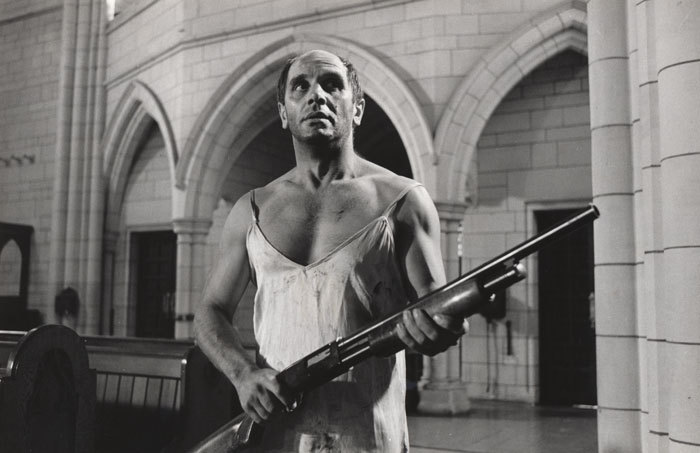

Bruno Lawrence in Smash Palace, 1981 - John Dix collection

Blowing It was centred around the NZ Symphony Orchestra and Bruno asked me to attend a rehearsal at the Town Hall in Wellington, where I was living at the time. Unfortunately, it clashed with a dental appointment but we agreed to meet after at the nearby Regent Tavern, where I found Bruno drinking with a musician friend. I couldn’t join in so the friend said, “Let’s retire to my place – I’ve got something to sort your pain, John.”

At home, he presented me with a vial of prescription liquid morphine. Bruno – “Actually, I’ve got a bit of a toothache too … no, I do, John, honest, don’t scoff, I do.” The thing is the incorrigible bugger was serious.

Bruno wanted to try everything. He carried a strict code of hedonism throughout his life. He could be very persuasive, often with consequences which didn’t affect him. When I told him about my sole experience with datura, which he’d never tried, it was as a cautionary tale, but Bruno said, “I want some of that,” ignoring my earnestly shaking head. A few months later he returned to Waimarama with a bottle of datura juice, using those powers of persuasion to coax me into participating. We immediately felt nauseous – I retired to my bedroom and levitated for 12 hours; Bruno spewed up most of his dose and was back to normal when I still had my nose pressed up against the ceiling.

The Crocodiles Mk.1: Tony Backhouse, Jenny Morris, Fane Flaws, Tina Matthews, Peter Dasent and Bruno Lawrence, 1979

Bruno loved the psychedelic drugs and he never subscribed to the hippie ethos that they were just stepping stones on life’s spiritual journey. He got as far as acid and stayed with it.

We tripped at concerts, the golf course, the movies (I can’t watch Glenda Jackson to this day without flashing back to the Lido in Wellington, where the usherette told us to be quiet, it was not a comedy). I don’t recall tripping at the racetrack but we did go to the Whanganui greyhounds, where I was convinced that a tumbling dog had been hit by a flying bottle (Bruno persuaded me not to report it). I accompanied him to an awards ceremony where everybody was so pissed no one noticed our increasingly aberrant behaviour. Bruno’s attempt to gee up the Members Stand at the Basin Reserve with a haka was a highlight; Bruno giving a bunch of rugger buggers in Lancaster Park a halftime discourse on the game was not – “Imagine the ball as a lump of shit and the players as flies.”

He would sometimes change the trip’s schedule at short notice. I said I’d pop in, we can always leave early. You’ve got to go where the action is. The “action” might include an art exhibition, book launch, fashion show, a mate’s BBQ. You wouldn’t want to invite Bruno to your party for him to leave early. Whatever else the night had in store would be shared with any number of friends, old and new, Bruno bringing the action with him, generally ending with music, nightclubs until dawn.

Bruno’s celebrity afforded access to the most prestigious events: courtside at the NZ Tennis Open (where he spent an inordinate amount of time adjusting the umbrella to improve the colours it cast) and one year we attended a swanky polo tournament on the Waimarama Road – we weren’t invited back.

There were other benefits for a celebrity. One day in Wellington he picked up a trifecta, a tidy little amount, enough to taxi around the known drug dealers and book into the Michael Fowler Hotel just to smoke some dope. We were stumbling around the foyer, no luggage, when the concierge swooped on us with what we assumed would be bad news. But it was yes sir no sir, full discount rate of course sir, happy to have your esteemed patronage, Mr Lawrence. We, the royal we, were upgraded to a two-bedroom suite. Rolling a joint, Bruno said, “Do you think we should stay here tonight, JD?”

At Athletic Park, sans acid, we witnessed Auckland trounce Wellington, largely as a result of their mastery of the rolling maul. Bruno, one-eyed Wellington supporter, was adamant that they had cheated. That evening he and Veronica went to dinner at The Settlement, where the victorious Auckland team was also dining. The team was chuffed to have Bruno Lawrence in their midst and, meal over, Bruno and Veronica were surrounded by admiring Auckland players. Until the third or fourth bottle of wine when Bruno called them a pack of cheats. Veronica placated them, “but they were very angry, John,” she told me later, “they wanted to punch him.”

I punched him myself once. He asked me to, nay – insisted. We’d had an issue and I was pissed off. “Go on, hit me, I know you want to.” “No, Bruno, I just want talk about this.” “You want to punch me, I can tell. Go on, hit me, get it out of your system.” On and on he went, avoiding the actual subject, proffering his jaw, a mistake. My hook landed flush, no damage but hard enough to dissuade from using this tactic again, with me or anyone else. He stumbled back, brown globes widened in disbelief. We went for a beer after, Bruno dramatically nursing his jaw every time I glanced at him.

Boxing wasn’t one of Bruno Lawrence’s sports but he competed in soccer and rugby in his younger days, played social cricket in his 40s, and ended with a zero handicap in golf (I caddied for him several times, most hilariously at a celebrity tournament in Rotorua).

Bruno Lawrence in Quiet Earth

You can read these words and conclude that Bruno Lawrence spent his life chasing the next high when, in truth, he was first and foremost a family man. Veronica, their five kids and the mokos when they came were Bruno’s anchors, his lifeblood. Waimarama, the isolated community 25km from Havelock North, was where Bruno spent most of his time and that image of Bruno as the archetypal Kiwi bloke was accurate.

David Blyth told me that during the filming of Death Warmed Up Bruno refused the drive across a particularly hairy section of Skippers Canyon, insisting on walking. I don’t dispute Dave’s yarn but it doesn’t fit in with my experiences and I recall an occasion when Bruno was concerned about an incoming storm and a cracked branch halfway up an ageing poplar in the Snoring Waters courtyard. He ascended, me 10 metres below, reluctantly assisting with the transfer of the chainsaw. He was up there for an hour, positioned uncomfortably, refusing to descend despite the increasing inclemency.

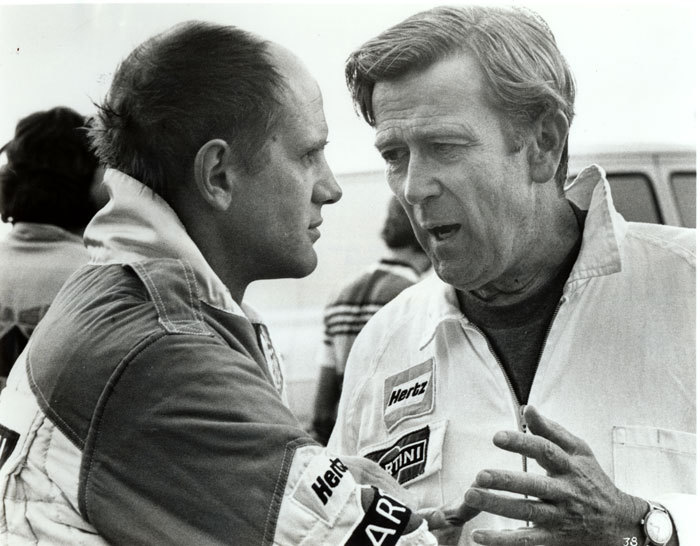

Bruno Lawrence and Anthony Hopkins in Spotswood, 1992

There was always a touch of bravado about Bruno. In 1974 he was filmed in Robin White’s Wellington studio, dressed as Superman for a BLERTA skit. Departing the building and locking themselves out, it was realised that something of import had been left inside, prompting Bruno to clamber up the drainpipe to an open window on the second floor. These suspicious activities were noticed and the police were interrogating the group when Bruno reappeared, still in costume. “And what is your name?” asked one of the plods. “You mean you don’t know?”

[20 years later he was still scaling drainpipes. At the 1994 Mountain Rock Festival, me working, Bruno kept an eye on Karenza and Dylan, driving them to our Woodville hotel in the early hours. They were locked out but had left open a window – no problem for Superman.]

Bruno had the Kiwi can-do attitude, even when he lacked the expertise. On one occasion, when we were the only adults present at Snoring Waters, Bruno had spotted a framed stained glass window in a Hastings demolition yard and wanted to surprise Veronica by installing it in their bedroom. It weighed around 150kg and it was a major effort getting it on and off the truck.

Three days later we were still farting around, half the bedroom wall had been taken out and there were pulleys, ropes and wedges, the window balanced precariously. Bruno slept in the spare room. Midway through Plan E, Bruno told me, “I’ve got an appointment in Wellington this afternoon … ” Hmm, l hope you’re back before Veronica, Bruno …

When the “commune” started, the influx of children enabled the Waimarama school to retain two teachers (husband-and-wife John and Kiri Moeke). In the early-1980s the kids wanted to participate in a team sport but, with different ages and genders, they didn’t have enough players without amalgamating with the Maraetotora school, which didn’t appeal. At Bruno’s suggestion, a mixed age and mixed gender soccer team was formed, the Waimarama Rangers. Bruno was coach; I was his offsider, filling in as required. John Moeke had no interest but allowed use of the school bus. With no home ground, all matches were played in Hastings or environs. A routine emerged – game over, ice cream at Rush Munro’s and leave the team slurping while parked outside the Havelock North TAB. We’d spend maybe $10 between us, a Saturday afternoon diversion.

There’s no doubt that Bruno developed a serious gambling problem in his later years and I’m not sure when that started. He’d always liked a day at the track but that was just twice or thrice yearly, no major. In 1985, spending a weekend with us in Foxton, he collected a $1500 trifecta and it was only the closing of the TAB which allowed him to retain half of those winnings, my first indication that he was no longer punting sensibly.

During a later visit to Waimarama, Bruno asked me to accompany him into town, he had a few things to do. On the road he confessed that our destination was Gisborne. Gisborne? “Yeah, I’ve been given tickets to the Members Stand at Makaraka. But don’t tell Veronica,” he said, compromising me.

[“Don’t tell Veronica” were words I became accustomed to – big winnings on the gee-gees flitted away in a day, flights missed, outrageous behaviour. Don’t tell Veronica.]

By then Bruno Lawrence was a movie star and I met some notable people with him, although that worked both ways – Bruno introduced me to Anthony Hopkins; I introduced him to Joe Cocker. Bruno didn’t get to meet Willie Nelson but he did meet Willie’s drummer, Paul English.

I passed through Queenstown with Paul English when Bruno was there filming Race For The Yankee Zephyr and, it turned out, the film crew had a day off. Paul, a good ole Texas boy and don’t forget it, wasn’t enthusiastic about hanging out with an actor. But he’s a drummer, I told him. “Does he play country?”

We arrived at the crew’s motel around 9am but Bruno had failed to surface as arranged. Hearing sounds from what had been the previous night’s party room, we entered to see English actor Donald Pleasence draining the dregs from left-over drinks. “My dear fellows,” said the slightly batty thespian, “could you possibly assist me in locating an alcoholic beverage which doesn’t contain cigarette butts?” Paul flashed me a look to kill. That’s not Bruno, I told him, relax.

As it turned out, we inherited Donald Pleasence anyway. Locating Bruno, we headed out for breakfast and Donald wasn’t missing out on the chance of alcohol in the mix. It was an interesting day – Paul didn’t drink, just dakked up; Donald didn’t dak but he sure as fuck drank. Paul, cold and surly until he’s approved you, lives on Texas time so it took him a while to warm to Bruno; he didn’t take to Donald at all. Donald seemed oblivious to everything except the next drink. In mid-afternoon Bruno challenged Paul, said he didn’t look comfortable. “You got that right. Ah’m not comfortable. Ah don’t like bar hopping without a gun and a knife.” “Goodness gracious me!” squealed Donald.

One day a friend said to me, “I’ve just watched a documentary on the Southern Alps and I swear I could see Bruno Lawrence’s features in the snowline.” I know what he meant, and so did Bruno. By 1990 he had appeared in over 20 feature films and television movies – he was everywhere! In danger of over-exposure, he made several trips to Hollywood, where many Kiwis were making their mark, but the USA never appealed, too far from home. The three-hour flight across the Tasman was more convenient and he was much in demand. In 1994 he was cast on the ABC series Frontline, prompting Veronica to join him in Melbourne. With the isolated Waimarama homestead lying vacant, I did a spell as kaitiaki, my longest period at Snoring Waters since uprooting in 1981.

David Gapes came down for a fortnight and one day during a clean-up he found a partly-buried statuette under the house. It was Bruno’s Best Actor Award for Smash Palace at the Manila Film Festival. When I told him, Bruno, feigning appreciation, said, “Oh, I was wondering where that got to.” Bruno Lawrence did not rest on laurels …

Stills from Smash Palace - Murray Cammick collection

Roger Donaldson has a great story about Bruno in Manila. They were guests-of-honour at a dinner given by Imelda Marcos but Bruno disappeared mid-meal. Upon investigation, he was found conducting the huge kitchen staff in a percussion symphony, banging pots and pans. There is much to understand about Bruno Lawrence in that tale.

[Bruno told me he befriended British actor Jeremy Irons in Manila and invited him to join the NZ table at the ceremony. Irons, frontrunner to collect the best actor award (for The French Lieutenant’s Woman) was taken aback when Bruno got the gong. Returning to the table, Bruno tripped, juggling the statuette. “Are you too heavy for that award, Bruno?” asked Irons drily.]

Not everyone liked Bruno, his politics, lifestyle and general demeanour alienated many. He could be blunt, rude even, particularly when music was concerned. In BLERTA, shortcomings could result in a drumstick thrown at the offender’s head. One Sunday evening at an Auckland restaurant, a hungover Bruno was so incensed with the inept pianist that he pulled out his wallet and said, “I’ll give you fifty bucks to stop playing.”

I know of several people claiming a Bruno friendship who he didn’t actually like, just endured. He could be downright disdainful to “personalities”. When I accompanied him to record a voice-over at TVNZ he was accosted by a television celebrity. They were casually acquainted but Bruno’s attitude was distant, almost rude, and I told him so as the hapless sycophant retreated. “So what? He’s a fucking wanker, he’s up himself. And he’s just a bloody television presenter!”

In 1990 Bruno and I were recruited to promote Rock The Quota, a campaign to increase NZ music on radio, both appearing on the promo video and then presenting copies of the single to Auckland breakfast jocks and programme directors. Our driver was a poor lass from Virgin Records who, around 7am, suggested breakfast because the next appointment was two hours’ away. Bruno coaxed her into driving to the Riverhead Forest to forage for magic mushrooms.

A weekend of concerts followed in Wellington, with Bruno and I as MCs. Prior to the main event, he fed me a tab of acid and then promptly disappeared, leaving me to carry the show. My mate Bill Payne reckoned I was the highlight of the night – “It was like watching Judy Garland at Carnegie Hall,” a reference to her onstage breakdown.

The quota video was shot at VidCom on a Monday morning, 8am start. Bruno had arrived the previous week for the Eden Park cricket test with India. We’d attended the weekend’s play together and it had been a fairly quiet visit by Bruno standards, mischief free. That was about to change.

He had intended to return to Eden Park for the final day’s play but catching up with all these musos changed the plan and we arranged to lunch at The Gluepot, where I was working, and watch the cricket on the big screen. By mid-afternoon, the match meandering to a draw, I had withdrawn to my office and our lunch companions had sloped off. Bruno was bored, always a danger. To his rescue came a group of film people, including Don Reynolds and Roy Billing.

It was around 5pm when the manager informed me that Bruno had emerged naked from the Corner Bar telephone booth. Oh, Superman again. An embarrassed bouncer was pleading with him to dress. Bruno, arms folded, was saying, “does my nakedness offend you?” It didn’t help that Bruno’s companions were in hysterics.

Anyone else would have been red-carded but Bruno’s presence was good for business and, clothed again, he was allowed to remain. There’s more, I won’t go into details, but suffice it to say that Bruno’s antics made a lengthy item on Metro magazine’s gossip page. Shortly after publication, Bruno flew in from Sydney; he hadn’t seen or heard about it. He read it at the airport magazine stand, muttering about suing the bastards. I told him that although it was filled with inaccuracies, the truth was actually worse. During the uncharacteristic silent drive into town, Bruno just sighed occasionally, wondering aloud whether Veronica had read the item.

Bruno Lawrence, obnoxious drunk? There were just two occasions over 20 years when I felt compelled to say the next day, “for fuck’s sake, Bruno, don’t ever do that again.” How blessed can a man be? A small price to pay for a hundred binges with the most sterling company.

Rick Bryant summed it up, succinctly as always. He said, “I don’t know whether Bruno Lawrence was a great man but he certainly had a great man’s funeral.” Bruno’s tangi at Waimarama’s Taupunga Marae was, indeed, an event. 1600 people meals were served at the hākari that evening. There were some fine tributes but the one that impressed me was a Māori guy who’d driven down from Gisborne – he’d never met Bruno but he spoke about the effect Bruno’s music and films had had on him. It was simple but heartfelt. No disrespect to Sam Neill and others who spoke but that kōrero brought home Bruno’s true importance in the cultural fabric of this country.

I can pinpoint the exact spot where I stood on Pompallier Terrace, cellphone in hand, when I fielded Rick Bryant’s call, succinct again, two words – “Bruno’s dead.” Karenza was in town for the weekend; we cried together. It was an awful day, an awful week. I felt later that I let myself down, let Bruno down, I just didn’t have it together, didn’t handle it very well at all. I was pissed most of the time.

Bruno is buried at the marae urupā, only the second pākehā to receive that honour. In 1996 came the hura kōhatu, the unveiling of the headstone. I arrived at Waimarama four days prior to spend time with the whānau but, it turned out, only Veronica and Bruno’s nephew Matthew Gordon were in residence. Matt was on a mission to construct Bruno’s headstone and had moulded a plinth on which a bronze Bruno “angel” fired by Liz Earth/ Sanderson was to be mounted; Fane Flaws provided ceramic tiles featuring the same words he had painted on Bruno’s coffin lid six feet below.

Matt constructed the gravestone over the next three days and I was his offsider, mixing and pouring the cement. I knew that I had unfinished business but I hadn’t anticipated blisters for Bruno. As others, more able-bodied than I, began arriving I declined to relinquish my duties or accept assistance. I started it, I’ll finish it, if only to go through life and be able to say, “I helped build Bruno Lawrence’s gravestone.”

Over the last 20 years many have dined out on Bruno stories, me included, even, if you like, composing these words right now, sharing his glory. But a lot of us have done that, eh, shared his glory? But what was that question?

“Do I remember Bruno Lawrence? Well I lived at … I dropped a lot of … I helped build … Yeah, I remember Bruno.”

Hei maumaharatanga ki te tino hoa, rangatira o pūoro …