A jazz player at heart, he had an ear for any style but his foray into rock and roll won him fame. His disarming sense of humour, including “blind jokes” and driving exploits, helped define the legend.

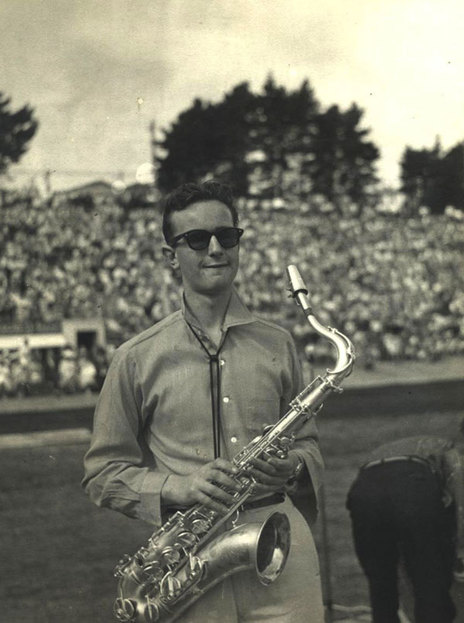

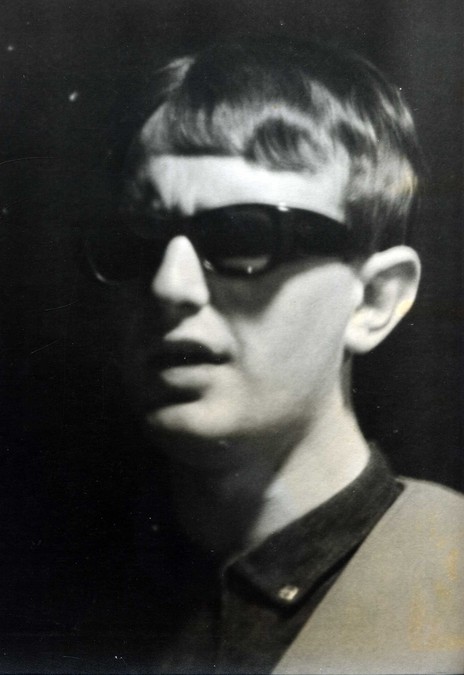

Claude Papesch moved to Auckland as a youngster. He was working at jazz clubs from the age of 16 and became a regular at the Point Chevalier Youth Club. It was there he first encountered up and coming rock and roll singer Johnny Devlin from Whanganui.

Devlin, the serial talent quest winner with his animated Elvis Presley covers, stunned the crowd at the Jive Centre in Auckland where he was offered a regular spot. His cover of Lloyd Price's ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ was a massive hit. Devlin’s team claimed they had sold 100,000 copies and it launched a long-term career.

Devlin was initially backed for smaller tours and his first two recording sessions by the Bob Paris Combo who played on a dozen recordings between August and October 1958.

Key to Devlin’s success was the masterful team who kept pushing his public profile: club owner and promoter Dave Dunningham, Prestige Records boss Phil Warren, and tour promotor and PR guru Graham Dent, who arranged to showcase Devlin across the nation’s network of movie theatres and concert halls owned by Dent’s employer Kerridge Odeon.

Dent milked every performance, ensuring maximum media coverage with pink Cadillacs, screaming teenage girls, torn shirts purposely sewn to fall apart when tugged and large royalty cheques signed for the cameras (and promptly ripped up afterwards).

After a lower North Island tour Devlin was back in Auckland recording 16 more tracks, allegedly in one night. The last of his previously recorded singles was hitting the airways just as the new batch were being drip-fed to meet the frenzied demand.

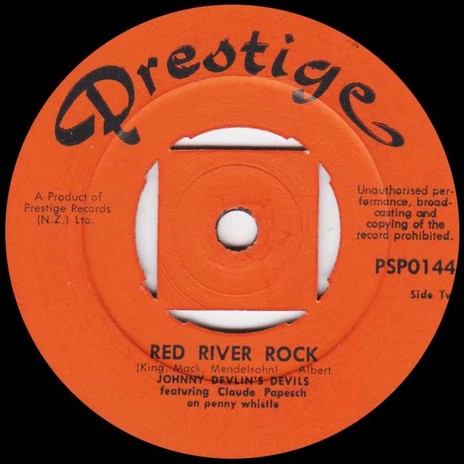

Devlin was preparing for a national tour in support of his recordings but the Bob Paris Combo weren’t keen. Dent asked his friend, piano player and saxophonist Claude Papesch, to come up with a replacement unit.

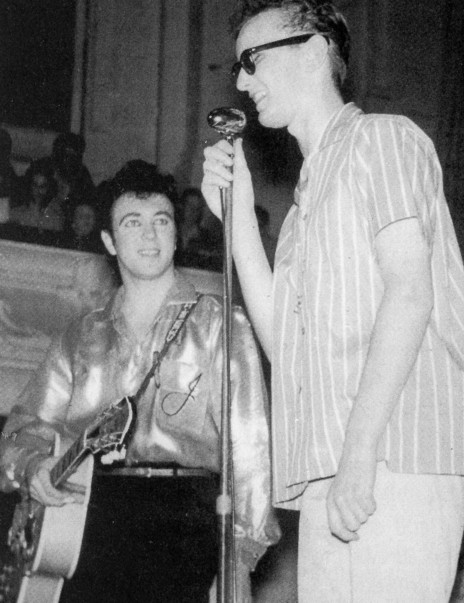

In early 1959, it was The Devils who laid down the sound for New Zealand’s king of rock & roll.

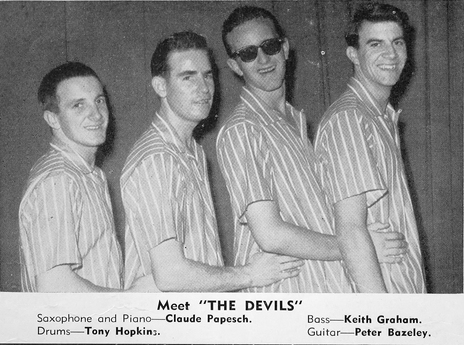

Papesch chose guitarist Peter Bazely, bassist Keith Graham and drummer Tony Hopkins to become The Devils. In early 1959, for Johnny Devlin’s third venture into the studio, it was The Devils who laid down the sound for New Zealand’s king of rock and roll.

Having won over the New Zealand market, the pressure was on in May 1959 to extend that success across the Tasman with Johnny Devlin & The Devils supporting The Everly Brothers on their Australasian tour.

Devlin and his band appeared on Australian TV shows Bandstand, Six O’Clock Rock, The Go!! Show and Teen Time and a Rock ‘n Roll Spectacular at Sydney Stadium alongside the best of Australian bands, which was filmed for a documentary.

In July 1959 they featured in the Battle of the Big Beat concert where Australian rock and rollers “challenged” their US counterparts including Lloyd Price and Conway Twitty.

Devlin quickly replicated his success across the Tasman with a string of hits. The Devils were now simply an option for Devlin who performed with a range of musicians, eventually returning to New Zealand, then expanding his career in both countries and making some inroads in the UK and USA.

Papesch remained in Australia alternating between solo gigs and joining other accomplished players in a variety of bands. Among his first outings was to join Devils guitarist Peter Bazley in The Leemen, backing Lonnie Lee, one of Australia’s top rock and roll and rockabilly exponents.

Bazley became known as one of Australia’s finest country music guitarists after winning accolades for his lead work on The Leemen album Johnny Guitar, the first No.1 record by an Australian rock band.

Devils drummer Tony Hopkins moved into the jazz idiom, initially teaming up with keyboardist Mike Nock in Kings Cross then moving on to contribute much to the New Zealand jazz scene over the next four decades.

In an interview with Chris Bourke for RNZ in 2001, Hopkins described Papesch as “a fantastic blind musician who played sax with the mouthpiece about as wide open as a door, and the reeds he used to use were almost strips cut off a bit of 4x2, and his sound was so harsh and rough. But he was a character, a great guy, we became very firm friends being on the road together all that time.

“In some ways he was a better keyboard player than a sax player, and he became known for his keyboard playing in later years after the Devlin show. He could emulate quite a few styles: Errol Garner, George Shearing – who was an inspiration to him of course being a blind pianist also – and he could play Ray Charles-style keyboard playing. He could play across the board, but he was always high energy, with a lot of enthusiasm.”

Papesch was planning to head back to New Zealand with fellow New Zealand saxophonist Brian Smith when they met up with Bob Gillett, a composer, arranger and saxophonist from California who’d been working with the ABC big band and in several jazz combos around Australia.

Gillett quickly found his niche, heading up Bernie Allen’s NZBC radio band; Smith went on to further his prominent jazz career and Papesch quickly settled into performing in Auckland jazz clubs and recording.

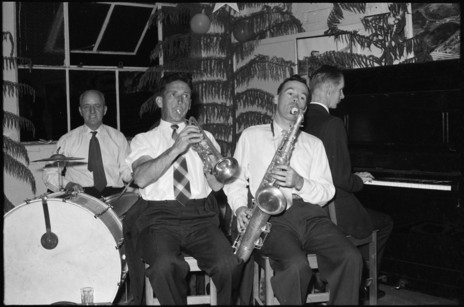

In 1960 he recorded the single ‘In Apple Blossom Time’ for Zodiac and the following year had a resident gig in Auckland with Kim Paterson on trumpet, former Devils sideman Tony Hopkins on drums, Andy Brown on bass, Australian saxophonist Bernie McGann and three blind female backup singers.

By the mid-60s, Wrote ‘PLAYDATE’, Papesch had become a “cool jazz exponent”

Papesch was in demand as a session player and appears on many recordings including those with singer Gene Pierson and the sessions for Peter Posa’s top selling instrumental, ‘White Rabbit’.

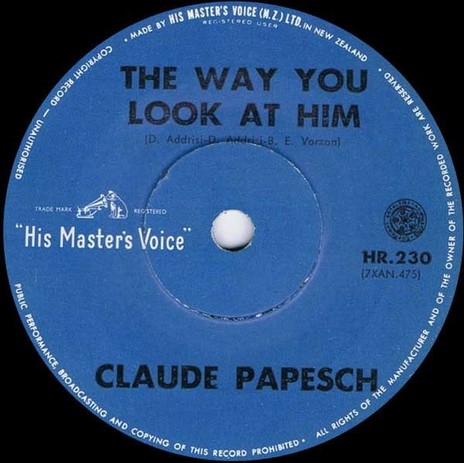

In 1964 he delivered two singles for Philips, ‘In The Chapel In The Moonlight’ and ‘Yoshiko’. In 1965 he recorded ‘The Way You Look At Him’ for HMV.

About 1965 Papesch was resident at the Auckland nightspot Copa Cabana, leading his own trio. He had evolved into a “cool jazz exponent,” reported Playdate. Papesch told the magazine, “It’s great to see that teenagers here are swinging over to jazz from rock’n’roll. I get terrific pleasure out of playing this music. My great interests are Negro blues and folk songs and this forms the basis for a lot of what I do. I’m a believer in jazz education in the schools – teenagers are ready for it, and would enjoy progressive even more than they do if they knew more about it. I intend approaching the Education Department about this.”

Murray Grindlay was with The Underdogs, resident at the Galaxie early in 1966, when he first became aware of Papesch. “Every night after the gig we’d head up the road to The Embers to hear the older than us musicians of which Claude was a mainstay. The blind guy playing the hell out of a Vox Continental was more than we could bear to miss … he sang pretty well too.”

He played with Doug Jerebine on guitar, Trix Willoughby or Bruno Lawrence on drums, Bob Gillett on sax and Yuk Harrison on bass and was more than happy to talk with the up and coming Underdogs, and even let them have a jam. “You can imagine how cool that was for us.”

Papesch then took Bruno to Sydney with him to back New Zealand entertainer Ricky May at the Latin Quarter in Kings Cross for a month or so but returned in May, performing and tutoring as the founder and head tutor of the New Zealand College of Entertainers.

Hi-Revving Tongues singer and bass player Chris Parfitt said he auditioned for a place and learned a lot from the master. “He spoke very deliberately, he taught us vocal harmonies, and the use of chords often using Beatles songs as a reference. I later saw him in 1969 with Electric Heap at the old Sydney Stadium playing Procol Harum’s ‘Quite Rightly So’ in a concert that included several Melbourne bands and Bon Scott singing with The Valentines.”

In January 1967, Papesch met with The La De Da’s at one of their rehearsals and heard their concerns about choosing the right song for their next release. The band had soared to success with ‘How Is The Air Up There’ but needed a boost after their second single failed to chart.

He sat down at Bruce Howard’s keyboard and played them Bruce Channel’s song ‘Hey Baby’ which they all agreed could be their next hit. Just as Papesch, predicted it took them back up the NZ Hit Parade, knocking The Beatles ‘Penny Lane’ off the top spot by March 1967.

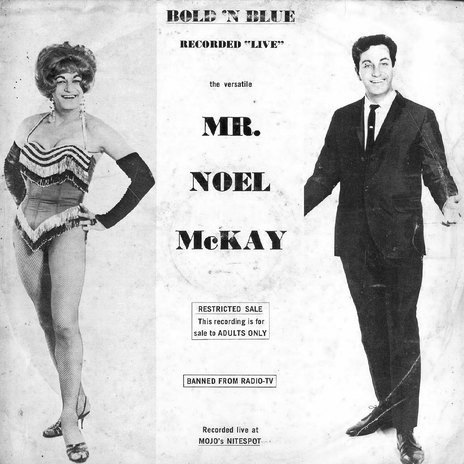

Former Hello Sailor guitarist and now-director of MAINZ (Music and Audio Institute of New Zealand), Harry Lyon, was a regular at Mojos, upstairs on the corner of Queen and Rutland Streets in Auckland around 1967-68 when Papesch’s CP Group had a residency.

“The band was Claude on Hammond, Jimmy Hill on drums, Doug Jerebine on guitar and Tommy Ferguson on vocals. Jerebine played bass when Claude wasn’t using the Hammond bass pedals. Sometimes The Chicks would show up after doing their round of floor shows in the burbs and help out with BVs. Just fabulous and inspiring.”

Papesch also had Electric Heap, a jazz trio with former Ray Columbus and The Invaders bassist Dave Russell and Bruno Lawrence, playing the Monaco and The Galaxie in Auckland. They headed across to Sydney, adding Tim Piper from Chants R&B and The Breakaways to replace Russell, who remained behind as a session player for producer and saxophonist Jimmie Sloggett.

Murray Grindlay recalls The Electric Heap gigs at the Galaxie. “The Underdogs had improved somewhat by this time and I noticed Claude would always listen to our set. When they moved across the ditch and were on the same circuit as Max Merritt and other leading Aussie bands the reports filtered back that they were holding their own.”

In August 1969, Papesch on organ and Piper on bass guitar joined New Zealand singer Glyn Mason (ex-The Rebels) and drummer Ace Follington (later with New Zealand band Bitch touring the UK) for a short stint in respected Australian blues band The Chain with blues guitarist Phil Manning.

The New Zealanders were in time to record the band’s first single, ‘Show Me Home’ on Festival Records, which according to the Milesago site, is regarded by many as the earliest example of the “OzRock” “progressive” style developing rapidly on the scene.

Grindlay says he decided to give Australia a go in 1969 but the band he joined didn’t work out so he was getting desperate for a gig. “Claude and I were both living at the Plaza Hotel. Electric Heap had just folded so we formed a band called Savage Rose. I hated the name so much I called it Claude’s Band.”

They enlisted the services of New Zealander Red McKelvie on guitar and Australian drummer Ace Follington, scoring the gig as the house band downstairs at the Whiskey a Go Go five nights a week, the Hawaiian Eye one night and The Electric Circus on the remaining afternoon.

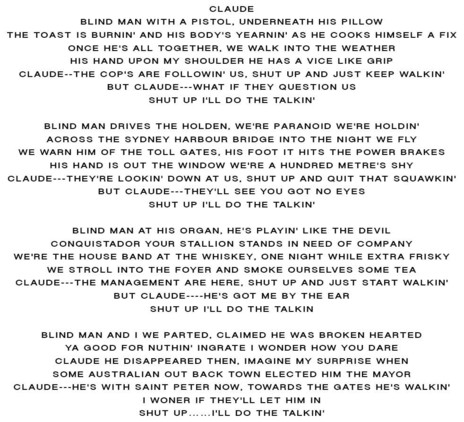

The unit was a covers band with Grindlay handling most of the vocals although Papesch also sang; his big number was Procol Harum’s ‘Conquistador’. “It never ceased to amaze me, him singing his heart out … hands flying round the double keyboard of the Hammond B3 we had to lug around … feet pounding out the bass line on the pedals. Even for a sighted person this would be incredible.”

But that, says Grindlay, was Claude. “He was bloody incredible. He would sometimes explain a musical question to me but, most of the time the lessons were learned on the bandstand. He played an enormous part in my musical education and for that I'll be forever grateful.”

In late 1970 Te Miringa “Milton” Hohaia (later an advocate for Māori land rights and Parihaka Peace Festival Director) replaced Grindlay as singer in the band, which still featured Piper on guitar and now had Trix Willoughby on drums. Music historian John Dix heard their last performance was at a big rock festival, presumably Wallacia, in January 1971. Hohaia later commented on Papesch’s sense of humour: “Claude told me he liked my dancing.”

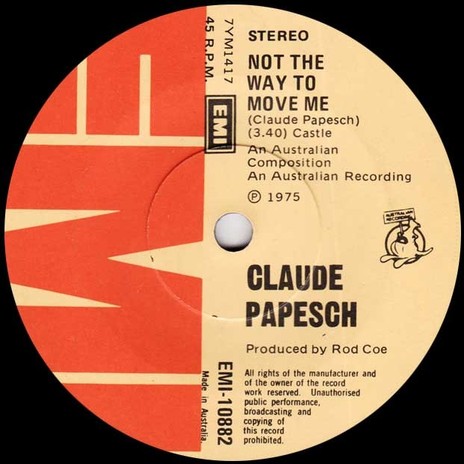

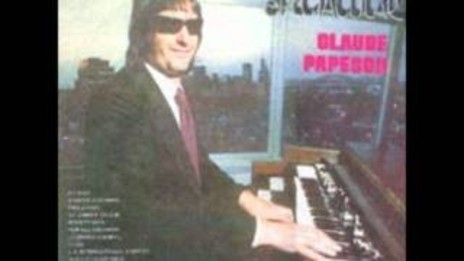

Papesch worked solo in the 1970s and recorded two albums of standards on the Hammond organ.

Papesch worked solo in the 1970s and recorded two albums of standards on the Hammond organ, on which he was a much respected master. The 1973 Hammond Spectacular on EMI had its sequel the following year, Hammond Electrique, which featured an early use of the Moog synthesiser. They were issued in New Zealand on the Zodiac label.

Papesch’s last known recording was a solo single in 1975 called ‘Petra’ for EMI, an early entry into what is today called the lounge genre. He eventually settled in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, continuing to play jazz but also out working his interest in civic service by standing for the Blue Mountains City Council.

Dix says the last time he saw Papesch they’d arranged to meet at the Sydney Musicians Club in Surry Hills. “Claude was living in the Blue Mountains. He caught a train and while not a regular, people greeted him more as a long lost friend. He chose to meet at the club because of its proximity to the central railway station.”

They didn’t stay long. “I’d picked up, perchance, Dave Russell and Jimmy Hill on my way there and we all taxied out west somewhere to catch Kevin Borich, who had Kerry Jacobson on drums. We partied into the night, Manzel Room at midnight, Benny’s at dawn and breakfast at Sweethearts, the whole bit and then Claude caught a train around 11am.”

Singer Tommy Ferguson says Papesch was “a magic man in every way.” He recalls an incident when working at Mojos with Papesch, Lawrence and Russell. “When I went to pick up Claude at the end of Dominion Road he said he wanted to drive. I said you’re joking. But no, he wasn’t.”

Ferguson said Papesch’s instructions were simply, “ ‘Just tell me whether the lights are green or red’. He drove to the top of the street and stopped when told it was red and we were off again when I said green. He drove all the way down Dominion Rd into Queen St and down into Mojos and never missed a beat.”

“Everyone’s got a Claude driving story,” says Dix. He recounts Yuk Harrison’s tale of Papesch driving the band over the Auckland Harbour Bridge for a “smoke” between sets.

“Bruno told me about Electric Heap heading back to Sydney from Adelaide; everyone was tired of driving, and Claude took the wheel along one of those 100km straight stretches, hugging the side of the road to keep on track. Everyone was dozing until it was noticed that the headlights hadn’t been switched on. ‘Who cares?’ said Claude.”

Another friend recalls dropping Papesch off at his place in Paddington after he played a gig supporting Renee Geyer in 1972. “You wouldn’t have thought he knew where we were but all of a sudden he said ‘pull up here for a minute’. So he gets out of the car, walks straight into a liquor store buys a bottle of plonk and then we’re on our way again. He knew exactly where we were.”

In 1984 Claude Papesch was elected Deputy Mayor of the Blue Mountains City Council. He also represented the Blue Mountains, Lithgow and Rylstone on Prospect County Council. His failing health due to cancer caused him to resign from public life. He died on 2 February 1987 aged 45-years.

The tribute in one of the local Blue Mountains newspapers was headlined “City Mourns Man Who Helped the Little Guy”. As a memorial to this much-respected musician and public servant, a commemorative tree was planted at the Wentworth School of Arts.