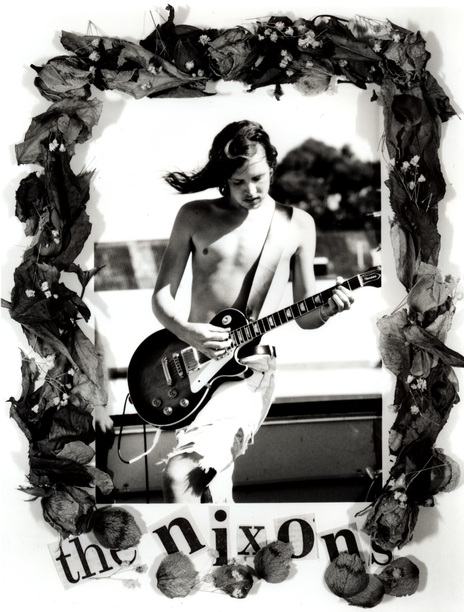

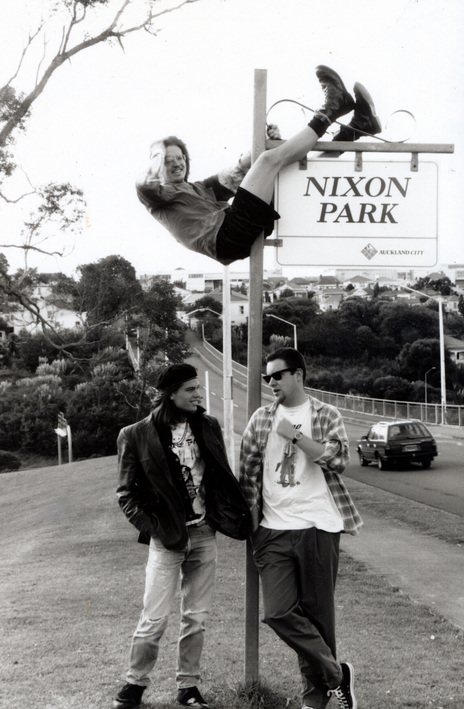

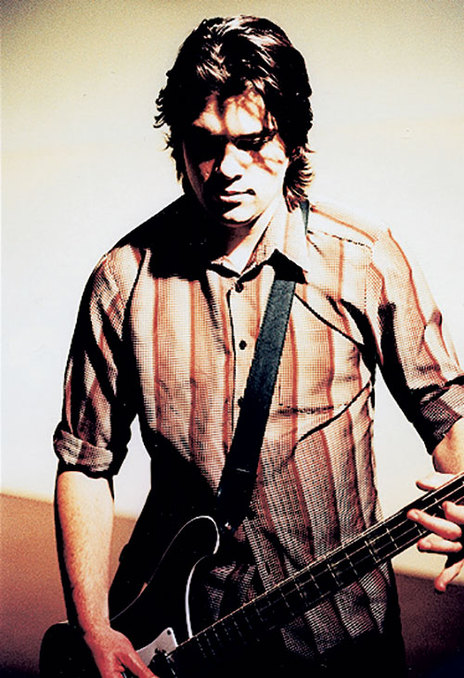

The Nixons started out as a loud indie rock trio in Auckland in 1990, a few years prior to the heyday of “alternative rock.” Frontman Sean Sturm had long, tangled black hair and played guitar through layers of effects, giving an electronic edge to his playing. The songs were given forward propulsion by the heavy hitting of drummer Mark Pollard, and the busy bass lines of Michael Scott, who cranked up the treble to cut through the fuzzy waves of guitar.

Sturm recalls wanting to emulate the propulsive rhythm sections and atmospherics of groups like Fugazi, Slint, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, and Jane’s Addiction: “It was a reaction against the Velvet-Underground-influenced Dunedin sound that dominated the local scene at the time. Our closest points of reference locally were Straitjacket Fits, Bailterspace and SPUD. Oddly though, people never seem to see these influences in our music.”

In the era of we-can’t-be-bothered-dressing-up Flying Nun bands, they came across a bit too earnest and well dressed for some (even applying a bit of gothy make-up for music videos). They also weren’t ashamed to admit they wanted to make a career out of music. What’s more, Sturm was studying English at university and had a side interest in philosophy so hence the band’s lyrics. He admitted in a RipItUp article, “we are pretentious!” On the track ‘Eye TV’, Sturm sounded more like a troubled existentialist than a rock singer – “How can I know? ... Nothing is quite as it seems.”

Their first release was a song, ‘Song To’, on the Freak The Sheep (1991) compilation put out by Flying Nun, but this was as far as their association with the label would go. Instead they surprised many by signing to Pagan Records, who were more known for pop acts like the Holidaymakers, Greg Johnson Set, and Tex Pistol or the roots music of The Warratahs and Chicago Smokeshop (though the label did also release early material by Shihad and Hallelujah Picassos). Sturm was nonetheless keen to work with label owner, Trevor Reekie: “We signed with Trevor because he seemed to understand what we wanted to do: complex pop music.”

The Nixons’ debut album, Eye TV (1993) was recorded at York Street Studio with Malcolm Welsford, who would soon become known for his ability to record massive sounding rock hits.

The Nixons’ debut album, Eye TV (1993) was recorded at York Street Studio with Malcolm Welsford, who would soon become known for his ability to record massive sounding rock hits (think: Shihad, The Feelers, etc). It was mastered by Welsford and Karl Steven from Supergroove – and the latter then took them out as a support act for a national tour. Student radio got behind the band and their music videos managed some play on late night television, giving them a solid base of fans throughout the country.

Pollard also arranged a fun way for the band to generate a bit of extra income by setting up a jam band on the side, which played a regular slot at Pelican Club on Elliott St. These sessions gave Sturm the opportunity to play Rhodes electric piano and saw the trio experimenting with soul grooves and classic R&B.

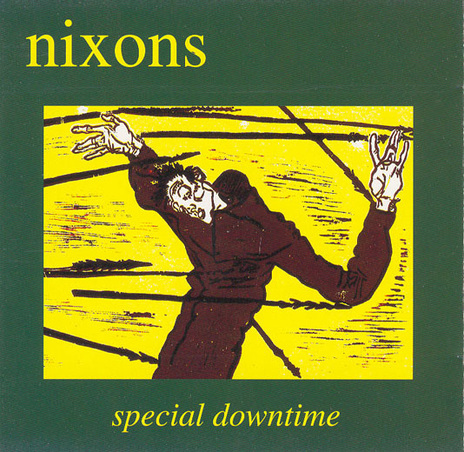

Just as The Nixons were preparing to return to the recording studio, they lost a vanload of gear to thieves – all their amps, guitars, and pedals were taken along with a full PA setup. Bought new, the haul would’ve amounted to over $50,000 of equipment. The Nixons went ahead with the recording anyway – borrowing gear for the rhythm section, adding Rhodes to the mix, and using an acoustic guitar to replace the electric. But rather than being a lightweight unplugged effort, the resulting eight song EP, Special Downtime (1995), was something far darker and atmospheric, with all the songs written by Sturm over an inspired two weeks leading up to the sessions. The title referred to the fact that it was recorded at York Street during the summer break, when the studio would usually be closed. The controls were manned by young engineer, Andrew “Tooth” Buckton, who allowed more room for the band to produce the work with him. The lyrics captured the band’s low periods (‘Down With A D’) and the feelings of self-doubt (‘Basement Static’), with Sturm asking, “may be the trapdoor to the attic? ... or is it only basement static?”

The strong, unexpected statement made by this EP coincided with other changes within the band. Reekie played their music to Ashli Lewis (who worked for the San Francisco-based management company representing Primus and The Melvins) and this this led to Lewis releasing the band on her own indie label, Incandescent, in the USA. The label packaged their first album and EP together as a debut release, then helped organise a tour to promote it with Buckton signing on as their soundman. They also inked a deal with small Australian label, Silent Echo.

There was only one catch – there was a grunge act over in the USA called The Nixons and they were signed to major label MCA, so the name was changed to avoid legal issues. The (NZ) Nixons now became Eye TV.

Unfortunately, it would start without Pollard, since he couldn’t commit to touring the USA. Scott knew the perfect replacement – Luke Casey, who had previously played with him in hardcore band Bygone Era. At the time, Casey was on a cabaret tour with Ted Clarke (of the Backdoor Blues Band) in Singapore, but he bravely chose to throw in his paying job for one that paid next to nothing and Eye TV was born.

The band drove across the USA in a Dodge van – after their $600 VW van blew up 100 miles in – and tried to promote their album show-by-show.

From October to December of 1995, the band drove across the USA in a Dodge van – after their $600 VW van blew up 100 miles in – and tried to promote their album show-by-show, sweet-talking their way onto air whenever they found a student radio station en route. They only had $10 per day to feed themselves and relied on taking any free sleeping space that was on offer. After one gig, they were told they could sleep in the venue, because the owner loved Kiwis and their passion for partying. He was very disappointed when the members of Eye TV didn’t want to drink all night and they were later woken by him having sex with a woman on a pool table in the same large room in which they were sleeping.

Then there was the stress of being constantly stopped by the local police just because they had out-of-state plates – Casey got out to show his licence to one officer and ended up staring down the barrel of a gun.

But there were upsides too, including a packed show supporting Mr Bungle and playing at the legendary New York venue CBGBs and opening for Tim Finn in ALT (with Andy White and Liam Ó Maonlaí) at the Great American Music Hall.

In 1996, they completed a month-long tour of Australia in May (including shows supporting Def FX) then in September they did another three-month tour of the USA.

However, driving from coast-to-coast in the years before GPS arrived wasn’t always easy. They got lost in one neighbourhood in San Francisco and phoned their label for directions, only to be told that they happened to have stopped in one of the most dangerous neighbourhoods in the USA and should get out of there immediately.

At one show in Nashville, an audience member threw a shower of $20 notes across the stage.

At one show in Nashville, an audience member threw a shower of $20 notes across the stage and then, after they’d finished playing, offered them a record deal on the spot. The man worked at SESAC (Society of European Stage Authors and Composers) and was seemingly well connected – but his offers came to nothing. They struggled onward, but their lucky break in the USA never came.

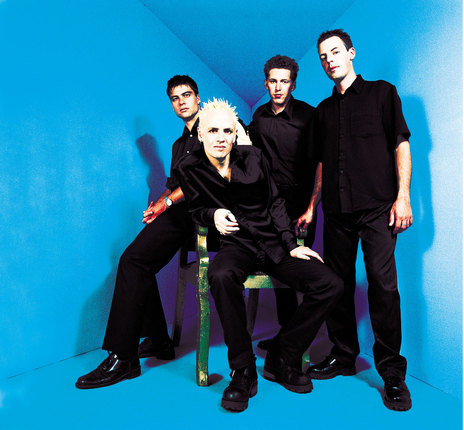

The music scene had slowly changed over the years since they started. Being the newest noisy, long-haired band was now beginning to seem a little passé. Sturm cut his hair short and spiked it up – dying it black and then red, before settling on peroxide blonde a couple of years later.

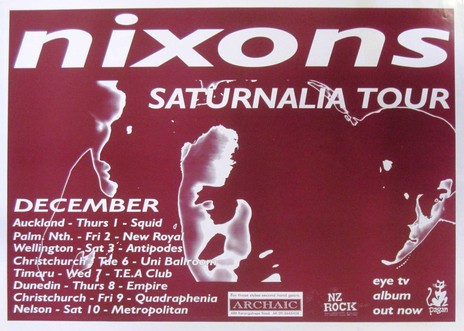

Their next album Birdy-O (1997) saw them reach a new, sharper level of production thanks to the work of rising young sound engineer, Chris van de Geer (who produced everyone from Greg Johnson to punk band, Muckhole, and whose skills would later push his own band, Stellar, to the top of the charts). Again, they negotiated studio rates by booking out Airforce Studios at an unpopular time of year – during the break between Christmas and New Year – then finished it off at The Lab. The first single, ‘Snakes and Ladders’ received great support form Auckland’s newly arrived music channel, Max TV, while the follow-up – ‘Wish It All Away’ even managed some airplay on local commercial radio.

Sturm felt the album did a good job of capturing the cohesiveness of the band at the time: “Luke had a broader range, which allowed us to experiment more with rhythms and arrangement. This allowed me to get much closer to Bad Brains, Jane’s Addiction, etc. The record also contained our best recorded performances because we had toured so much in the couple of years since Special Downtime. The record didn’t take off because it was rather too complex — and our golden run on bFM was over. As soon as we started being played on the new rock radio stations, they dropped us like a stone!”

Yet, trends from overseas suggested that an indie band could crossover into the mainstream without completely selling their soul and Eye TV seemed well placed to make this transition. Pagan Records had also reacted to the changing times by splitting off their more cutting-edge acts onto a new imprint – Antenna – and Eye TV were to be one of their key focus acts.

Radio lapped it up, pushing the single to No.13 and the group used this success to promote an anthology of their work.

After having a taste of radio play with their previous single, they decided to pursue this direction further by recording their next single at Beaver Studios with owner Simon Holloway, who was more well known for working with hip-hop and pop music acts. Drum parts were cut-up and looped and guitars were given a boost of compression to create a more cohesive sound, while Sturm’s vocals took on a more relaxed delivery (far from the strained passion of their debut album). Fortunately, the band had a song that was hooky-enough to make the transition to this pop-orientated sound. ‘Just the Way It Is’ had an addictively memorable chorus that was boosted by the soulful backing vocals of jazz singer Caitlin Smith. Radio lapped it up, pushing the single to No.13 and the group used this success to promote an anthology of their work to this point, As Far As The Eye TV (1999).

Working with Holloway pointed a new direction forward and, after 10 years in the music industry, it struck Sturm that it would be a good time to make some changes to the group’s sound: “The problem for us was that once we had outgrown bFM — and not really broken through in the USA — there was nothing for us to do in NZ but write for a broader audience. We didn’t have the luxury at that time of remaining underground, like most of the bands we followed in the USA. At the same time, we wanted to indulge our interest in late-60s soul music like Curtis Mayfield, Sly Stone, Bill Withers, and so on.”

They added a fourth member to the group – jazz keyboardist Grant Winterburn – who added a new melodic range to their tracks, recording parts on Wurlitzer, clavinet, and Rhodes. It some ways, it harked back to their days as a jam-band at Pelican Bar and their new tracks fused this soul sound with what they brought from their background in alternative rock.

the organ-heavy ballad ‘One Day Ahead’ reached No.9 on the charts and stuck around for an impressive 18 weeks, pushing the album to No.10.

The resulting album, Fire Down Below (2000), was an odd beast – moving from catchy rocks tracks (‘The Doo Song’) through to more dancey numbers (‘Déjà vu’ and ‘Fire Down Below’). Although Sturm enjoyed learning about digital recording, his focus was distracted by the task of completing his masters degree and the album ended up being a patchy effort. But the album did produce another remarkably successful single – the organ-heavy ballad ‘One Day Ahead’ reached No.9 on the charts and stuck around for an impressive 18 weeks, pushing the album to No.10.

If long-term fans of the band hadn’t been confused before, then they were completely befuddled by this stage. The result was that while Eye TV were great at finding new fans, they weren’t always able to take the old fans with them in the process. A year later, the effort of continuing to shed their skin and start over, finally wore them down and they folded.

Looking back, Sturm now believes that the band were limited by a number of different factors: “Firstly, we never played old stuff: once we had a new bunch of songs, we played those and ditched the old ones. Second, we were always too versatile for our own good: we didn’t have a style. Third, we were always perceived as an obscure mainstream band, when in fact we were a populist indie band.”

Sturm and Scott returned to academia after this. Scott eventually joined the Sociology Department of Flinders University in Australia and published the book, Making New Zealand's Pop Renaissance: State, Markets, Musicians (2013) and he continues to play music on the South Australian country and rock and roll circuit.

Sturm completed a PhD in English, which led him to become a lecturer in the Academic Development unit at Auckland University, though the desire to make music never quite left him. He teamed up with songwriter, Mahuia Bridgman-Cooper – a multi-instrumentalist (violin, keyboards, guitar) who works professionally as a composer for film and television (as well as writing string parts for Brooke Fraser, Lawrence Arabia, Paul McLaney, and his own string quartet Forvari). The Exiles’ debut single, ‘The One’, in 2006 made them the first local group to chart via downloads and radio play alone (it hit No. 29, promoted by an impressive CGI-enhanced live action video).

Luke Casey went on to jazz group Relaxomatic Project and formed his own group, Tinpot Guru. He now teaches drums and plays professionally around New Zealand.

Sturm and Bridgman-Cooper continue to make music as ‘School for Birds’. Of course, it sounds nothing like Eye TV (or The Nixons, for that matter) and Sturm continues his journey into new forms of music, always taking an unexpected path forward.