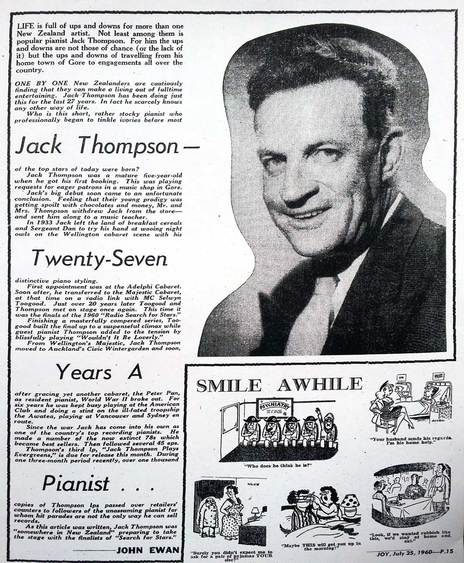

It’s very easy to take the mickey out of Thompson, but it’s also redundant; he never took himself seriously. He was born in Gore in 1908, and from the age of five he learnt classical piano. His first public appearance was also at five, playing the piano in the window of a Gore music shop. As a child he won piano competitions and music scholarships, but instead at 14 he became a dance-band pianist at the St Mary’s Ballroom in Invercargill.

By 1933 he began a long stint of playing for bands in the leading cabarets in the country.

Soon, his talents were noticed by visiting musicians, and by 1933 he began a long stint of playing for bands in the leading cabarets in the country: the Savoy in Dunedin, the Mayfair in Christchurch, the Majestic in Wellington, and the Peter Pan and Wintergarden in Auckland.

He married in 1933, and had a daughter, but led a peripatetic lifestyle. In 1936 the Australian Music Maker reported, “Jack has recently been initiated with the Peter Pan band and has settled down nicely, and apart from a few ultra-late nights and black eyes and things he is doing quite well.”

Before the war he had stints playing on board cruise ships, and in the US and Australia. Most of the country’s top band leaders hired him at some point – in the early 1940s alone he played for Chips Healy, Lauri Paddi, Theo Walters, Bert Peterson, Johnny Madden and Art Larkins – but he didn’t stay with any of these bands for long.

“Jack lacked confidence in himself and he lacked self-discipline,” Healy told the NZ Herald’s Owen Shaw. “He just wanted to play the piano,” wrote Shaw. “He liked his beer and it cost him a lot of jobs.” Madden, who played drums around Auckland from the 1920s till the early 1980s, said, “Jack was sacked many, many times. But he was always asked back. He was such a funny man.”

He put more time into placing bets than practising the piano – even pausing recording sessions to whip down to the TAB.

Besides his skill at the piano, Thompson was known as an authority on horse racing. He put more time into placing bets than practising the piano – even pausing recording sessions to whip down to the TAB – but never had the same success.

His casual approach to life and music meant that people were convinced he played only by ear. In fact, he studied classical piano to ATCL level. “I still read music all right – I’ve got to,” he said in 1969. “I’ve got to play each of the new pops about six times with the music so as to memorise.”

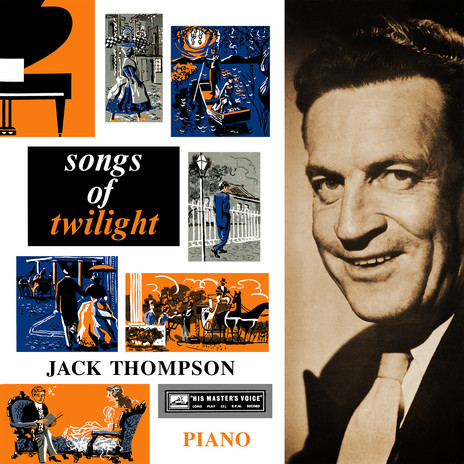

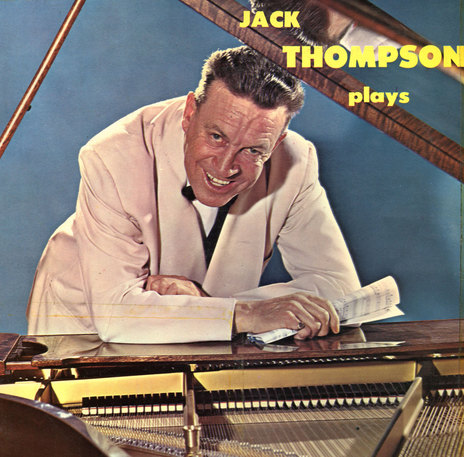

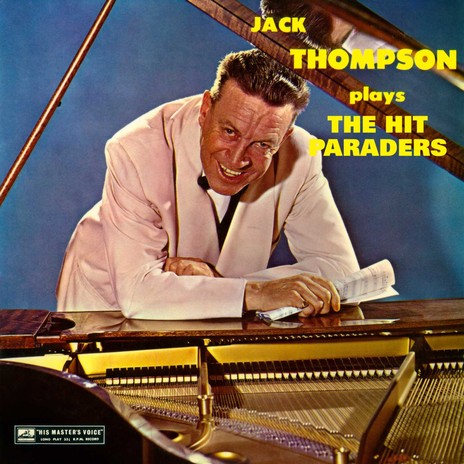

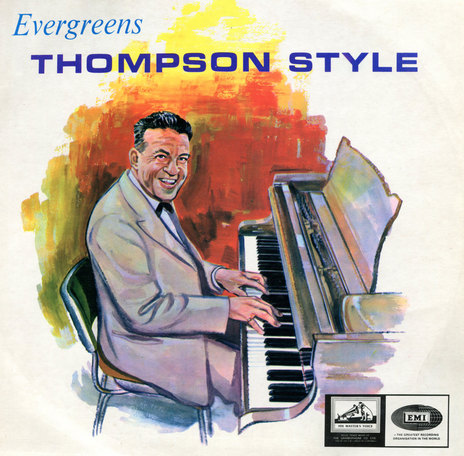

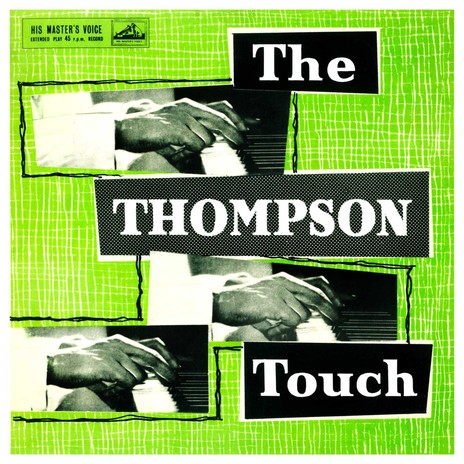

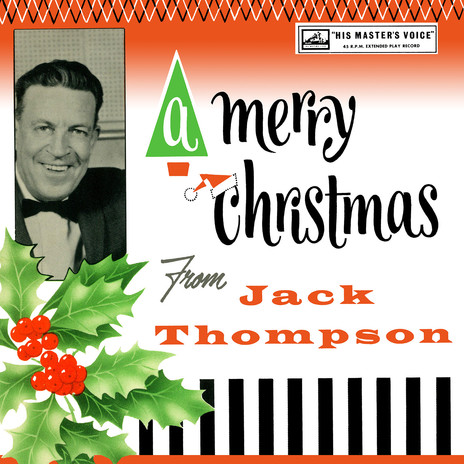

Having spent years playing small-town dance halls as well as the big, flash rooms, by the 1950s he had had enough and started recording medleys of popular favourites for release by HMV on 78rpm discs. These proved so popular that he eschewed playing with bands outside the studio. “I can’t stand dances,” he said in 1969. “Too hard-a work anyhow.”

He preferred performing in restaurants or studios or at weddings for a couple of hours. “I just like playing away in the background.” He just played what came to him, only preparing set-lists for recording sessions. “I like anything with a melody in it, jazz too with a rhythm. Some of these pop ones you hear would be all right, but in the jungle, wouldn’t they?”

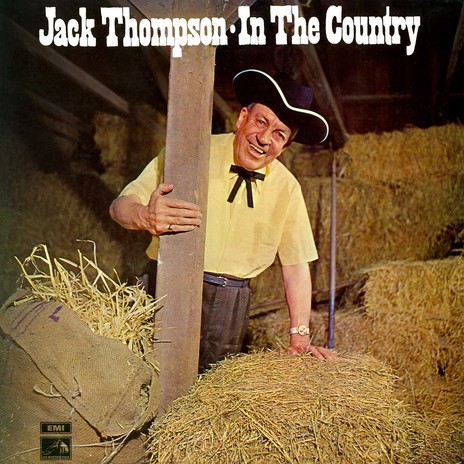

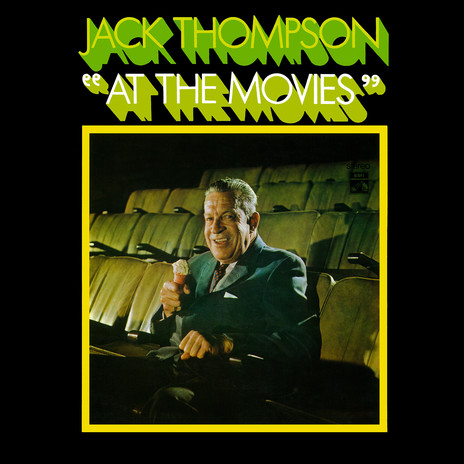

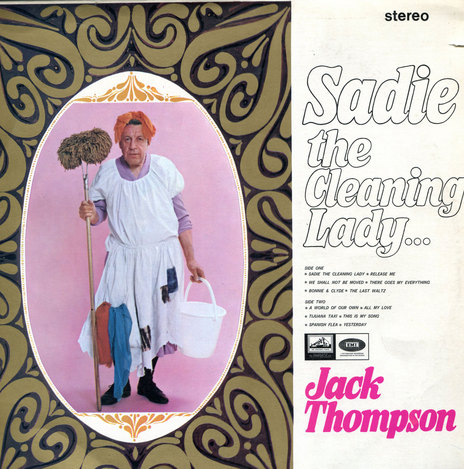

Thompson’s earliest LPs featured piano versions of party standards such as ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’, ‘Blue Skies’ and ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’. In the early 1960s, the albums took their repertoire from shows such as South Pacific, The Sound of Music and My Fair Lady. By the end of that decade he was getting hipper, recording ‘Sadie the Cleaning Lady’, ‘We Shall Not Be Moved’ and ‘Tijuana Taxi’. In 1970 the album Jack Thompson in the Country included ‘King of the Road’, ‘Deep in the Heart of Texas’ and ‘I Walk the Line’.

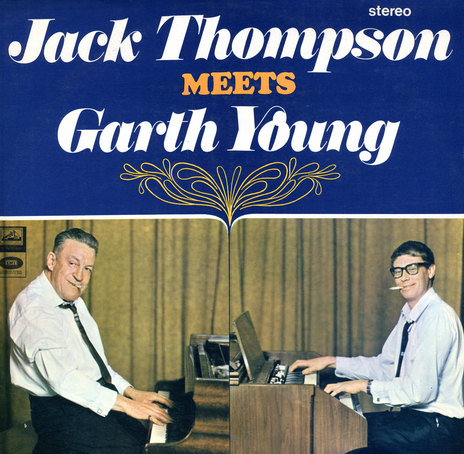

At HMV in Lower Hutt he was produced by Alan Galbraith.

At HMV in Lower Hutt he was produced by Alan Galbraith, well known for recording acts such as the Kal-Q-Lated Risk, Nash Chase, Highway, Rockinghorse and Mark Williams. In a gently mocking tribute to Thompson by the NZ Listener’s Steve Braunias, Galbraith recalled: “As a young producer, I got thrown the lot – the Salvation Army brass band, the Ngati Poneke Maori Club, Jack Thompson. And Jack was the only one who was ever any fun.

“He was a bloody good geezer. One of the classic old guys. Eternally positive. I can see him now; he was a stooped-over little guy. He’d sit side-saddle on his piano stool, all hunched over, with a U-shaped back – musician’s back, that’s right. He constantly had a fag in his mouth. And he’d hum the whole time he was playing – my hardest job was taking his bloody humming off the tapes. He’d fly up from Christchurch, and we’d sometimes cut three albums in a day. He never worked anything out. He’d say to the musicians, ‘Do you know 'Blue Danube' in C?’, and away you’d go. He enjoyed every minute of it. As soon as he started playing, his whole face would light up.”

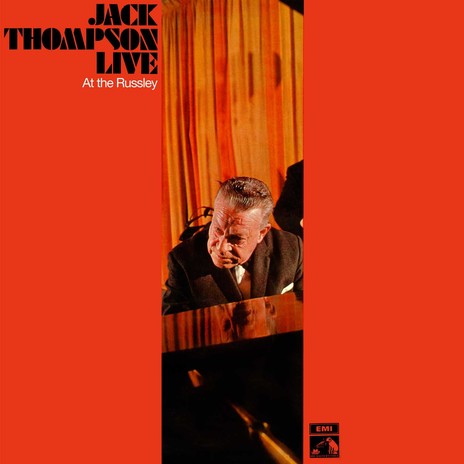

In the last years before he died in 1979, aged 71, Thompson played a residency at the Russley Hotel in Christchurch. One of these nights was recorded for his final album, Live at the Russley (1971). It was true that he liked a drink, and some nights he fell off his piano stool, always with a beatific smile. But an old friend neatly summarised what made him one of New Zealand’s most popular pop musicians: “He knew the music and knew what people wanted.”