After a career in New Zealand music lasting more than 50 years, Larry Morris passed away early on 18 January 2023. This interview first appeared in Real Groove magazine in two parts in 2001.

Other pages about Larry Morris at AudioCulture: Larry’s Rebels; Larry’s Rebels parts one and two; Larry Morris goes solo, 1969.

--

Larry Morris tried a few other occupations as a teenager before he discovered his true vocation of pop star, as lead singer for 60s band Larry’s Rebels. In the second half of the swingin’ 60s the band was omnipresent on TV, radio and stage with hits like ‘Painter Man’, ‘I Feel Good’ and ‘Let’s Think of Something’ and on newspaper front pages with headlines like “Screaming Fans Mob, Injure Town Hall Singer.” In 2001, after a long absence from stores, a Larry’s Rebels Greatest Hits album was released by EMI.

Larry's Rebels at the Top 20, Auckland. - Kurt Shanks collection

Larry did not come from Taumarunui and his navy career in the Navy was brief.

“I was born and raised in Ponsonby and I’m a Ponsonby boy in my heart, but my father was a trouble-shooting manager for the Farmers Trading Company, so any store that had problems, they would send Dad. We moved around.”

How did you join the Navy?

“We were living in Ngāruawāhia and I went into Hamilton and I saw this poster in this big window, ‘Join the Navy and become a man.’ I went home and I said to Mum, ‘I’m going to join the Navy, I want to become a man.’ Fuckin’ funny now when I think about it.

“So I joined the Navy as a seaman boy at 15 years old. I was a junior radar operator and I got my first draft to the Rotoiti, went out to sea and realised this is not for me, I was spewing and dry retching. Then I committed a cardinal sin in the Navy, I was on the wheelhouse duty, in the middle watch, midnight to 4am and I was so ill I lashed the wheel down and left my post to spew over the side. I didn’t want to spew in the wheelhouse because the able seaman in charge would come in and I would’ve got my nose rubbed in it, I was only a 15-year-old pipsqueak.

“Leaving your post is a no-no. They put me before a tribunal. They put me in a mental hospital, gave me shock treatment. I’ll never forget the psychiatrist at Oakley Hospital, I wanted to kill him. I managed to get word to my father and he went beserk, bundled me out of Oakley Hospital, put me in the family car and drove me back to Taumarunui. I was discharged from the Navy three weeks later because my father told them he was going to the press: ‘are you trying kill my child?’ They were trying to send me around the twist, fry me, they didn’t like my attitude. ‘You are not going to get away with this you little prick!’ Fortunately, Dad saved my arse and got me outta there. They gave me two series of shock treatment without my family’s approval, without my approval, just with the Navy’s say-so. The doctor was the head of psychiatry in Auckland. He’s dead now. Fuckin’ good job!”

It shows you how kinky men in uniforms are.

“Yeah, exactly. Bastards! I got an honourable discharge with all my back pay. I got a lot of money, that set me up until one day Dad said, ‘You’ve gotta get a job.’

Larry got a job at the Taumarunui sawmill.

“I was trying to unfreeze pipes at 5am and the boss said, ‘Go and refuel the muslin cloth and I’ll give you another light.’ There’s three 44 gallon drums and I was sure the one in the centre said ‘D’, but it didn’t, it was actually smeared at the bottom and it actually had a ‘P’ on it. As soon as the petrol hit the heat of the smouldering muslin cloth there was this massive explosion that threw me through the front of the shed and the sawmill burned to the ground. Everyone lost their jobs. They were going to kill me. I got a police escort out of town.”

Larry headed for Auckland and then the family relocated there too.

“Every morning Mum would come in with the Herald and say, ‘You’ve gotta get a job, son.’ I saw this little ad, ‘Stars wanted, can you sing? Benny Levin Promotions.’ I auditioned and Benny Levin and Russell Clark didn’t think I was that great but the guys in the backing band thought I was the bee’s knees and asked me if I’d join their band, the Rebels, and that’s how it all began.”

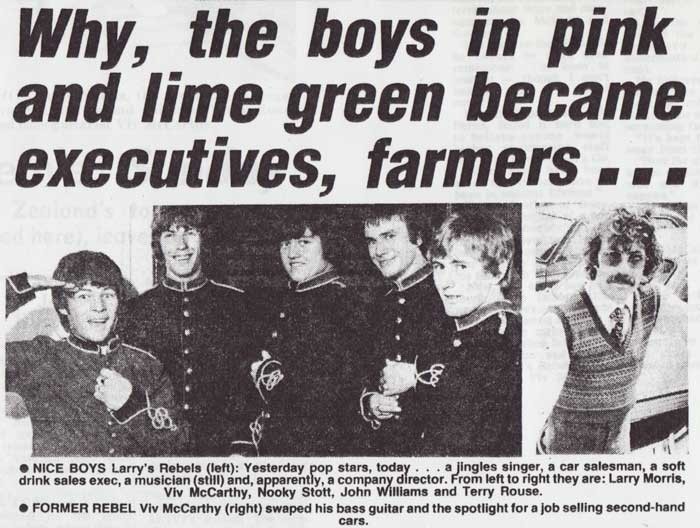

Larry’s Rebels in the 8 O’Clock, September 1980

Morris did not think Levin and Clark had a clue about talent.

“At the audition, I sang ‘Living Doll’ as well as Cliff Richard did.

“Max Merritt got us a Sunday Afternoon Club show at the Top 20 and there was hysteria. These girls started screaming. The owner of the Top 20 was Russell Clark. Russell came and seeing the reaction of the girls to the band, he offered us a contract and we signed with Benny Levin and Russell Clark the following week. As far as managers go, Russell Clark was the best. He was marvellous.”

In February 1966 the band toured with Herman’s Hermits and Tom Jones but they were not so keen on their Sunday October 9 booking at the Birkenhead Methodist Church.

“We all shuddered when Russell told us we were going to be playing in this church. He said ‘Larry, it will get us the front page of the NZ Herald.’ We’d already had two NZ Herald front pages.”

“One of the publicity stunts, Russell Clark nearly killed me. We were on a yacht doing a fashion shoot. I was wearing an elephant corduroy suit from Carnaby St, London. We’re out there in the Hauraki Gulf and Russell says, ‘Larry I want you to meet Miss South Pacific.’ The next thing, he pushes both of us in the water and he yells out, ‘Save her, save her.’ Fuckin’ save her? My elephant corduroy suit became this lead weight and I started drowning. I was trying to struggle out of this bloody jacket and some guy from the boat put a boat hook over and hooked me up. I’m half out of the water and Russell yells out again, ‘For God’s sake Larry, put your arm around her.’

What did Miss South Pacific think?

“She was a part of it. She never complained. She was, ‘I don’t know what I would have done without Larry, I felt myself going down, the next thing Larry had his arms around me.’ Bullshit! A guy had a hook in my jacket.”

The NZ Herald headline read “Cry of ‘Model Overboard’.” The story read, “A poor swimmer, Miss Wellford swallowed large gulps of sea water and submerged twice before Larry Morris, of the Auckland pop group Larry’s Rebels, dived in and rescued her.”

Did you spend a lot of time on those Impact recordings?

“Shit, no. We recorded the entire A Study In Black album in two days. It was such a prohibitive cost that Benny and Russell couldn’t get you out of there quick enough. Benny moved from Eldred’s to Radio NZ [NZBC, Shortland St] because Radio NZ was half the cost of Eldred. Benny would stand there and look at his watch all the time and it used to piss me off. I said to Russell, ‘I don’t want Benny here looking at his watch halfway through a take.’ Those recordings were all done very, very quickly. We found recording in Australia an absolute joy because there was no time restraints.”

“Benny was a Jewish businessman. Sometimes we found it hard getting our royalties out of Benny. They never ripped us off. They were very honest and scrupulously straight with us but it was a tough contract and Benny was a tough businessman.”

If you got royalties would you have been one of the few local musicians that did in the 60s?

“I think Benny paid royalties to everyone. When we were given the balance sheet for ‘Painter Man’ it had sold 6,000 units, we all jumped up and down and then we were given our royalties. Benny was very good in that regard.”

Was it a reasonable percentage?

“It was absolute crap. We had 18 or 22 cents to split among the five of us so four cents each 6,000 times was 240 bucks. A big selling single. The album A Study In Black, I never saw any royalties from that.”

In 1966 and 1967 Larry’s Rebels opened for numerous concert tour packages both in New Zealand and Australia. “The panache” of manager Russell Clark, and New Zealand promoter Harry M. Miller delivered the shows. Notable were the “Big Show” (Eric Burdon and The Animals; Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich; Paul and Barry Ryan) in April 1967 and the Walker Brothers, Yardbirds, Roy Orbison earlier that year.

“Harry would bring three artists out at a time and they were funny bills. You’d think, where does Harry get off putting these weird acts together? My favourite tour was the Yardbirds with Jimmy Page. I thought the world of Jimmy, he was a lovely, lovely guy. He’d come directly from Petula Clark’s ‘Downtown’ sessions in London, he was a wonderful session guitar player. The Yardbirds had fired Jeff Beck in Chicago before they left America to play downunder. So he was a little bit out of his depth and he was drawn to us because we were also the new boys on the block. He was getting booed when the Yardbirds would start. All these kids in their Union Jacket coats, ‘Where’s Jeff? Fuck off! Where’s Jeff?’ until they heard him play and then he had them. He was using a violin bow with his Telecaster then.”

“Jimmy Page and I and our guitarist John Williams became very, very close mates and we had some wonderful times. Memorable things, I can remember being naked in a bath in Lew Pryme’s flat, which in itself is a bit frightening, but fortunately Sandy Edmonds was in the bath with us and we were sitting there. We were so pissed, you know, there was nothing going on sexually.

“One of the last things Jimmy said to us was ‘Fuck I’ve had some fun!’ He gave John a guitar fuzz tone. We were just blown away and he says to me, ‘I’ve had so much fun with you guys, I’m gonna go home and form a band,’ and six months later – Led Zeppelin.

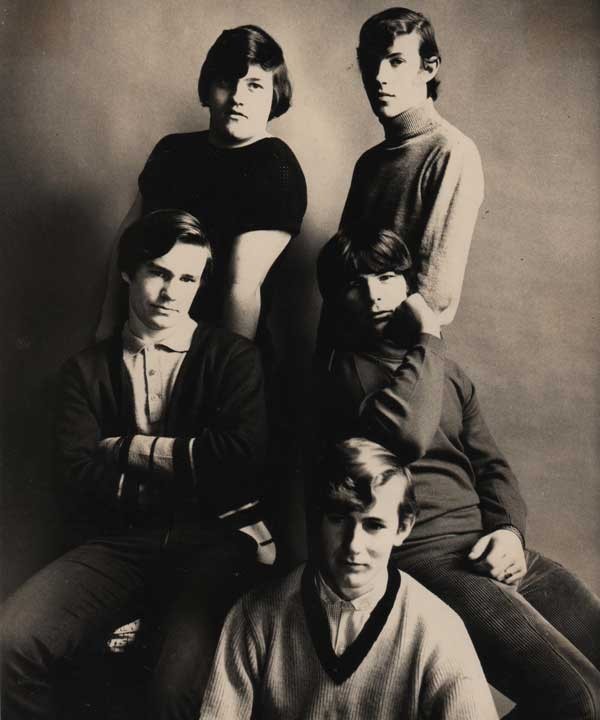

Larry’s Rebels - at back, Nooky Stott and Viv McCarthy; centre, John Williams and Larry Morris; front, Terry Rouse.

Although Ray Columbus and the Invaders did the Who and Small Faces tour, Larry’s Rebels played the Auckland Town Hall show.

“Pete Townshend gave us all of the Who’s Sunn amplifiers. At the hotel their English road crew chief came up to them and said, ‘You’re not going to believe this Pete. The excess baggage, they want to charge us more than the amps are worth.’

“Pete said, ‘Give the amps to the local lads.’ The guy said, ‘What?’

“And he said, ‘Yeah. Give them to these guys, they could do with them.’ I’ll never forget it, going ‘let’s get them now!’ Our road manager Nicky Campbell came back with a van full of these amps, courtesy of Pete Townshend.”

Were the Who and the Small Faces out of control?

“They weren’t very well behaved. None of us were. We were just hopelessly, crazily rock ‘n’ rolly. It was all done in good fun but you’d terrify hotel guests and hotel staff when they’d see you at three in the morning having food fights in the hall and ordering food from room service just to throw it at somebody. I’d never been there and yet these English guys were into that.”

In 1967 Larry’s Rebels scored the Australian Easybeats tour as the Australian band had No.1 in the UK with ‘Friday On My Mind’ and No.1 in Australia with ‘Sorry’. While they were away their debut album A Study In Black scored a four star review in Playdate movie and music magazine. Four stars was “Fab”, one star was “Dullsville”.

“Russell Clark was marvellous, he got us the Easybeats tour – he had the ability to pull these things off. We did the biggest ever support tour that you could do in Australia – that’s Russell Clark’s panache for you. I really wanted Russell to take over my career again, years later, but I frightened him. I absolutely terrified him – if I was in his office and he thought that I had a joint in my sock, he would freak out. He’s that square! But as far as managers, go he was the best.”

How did you go about recording? Who got you your sound – did the band or the producer have the major input?

“I think the band, we had our sound, but the engineers all had their own way of bringing it to the fore and putting it on tape. There were three guys who had a great influence in that regard. The first one was John Hawkins, who worked for Eldred Stebbing at Saratoga Ave, under the house, and that’s where we recorded the earlier stuff. Then we went to Radio NZ to record and we recorded under a guy called [Wahanui Wynyard] who was one of the first Māori broadcasting engineers. Lovely, lovely, guy who is still alive and living in England. And then in Australia, there was Roger Savage at Armstrong’s. Those were the three guys, but we basically had the sound when we came along. What we didn’t have as kids, we weren’t songwriters. Our first forays into writing – you could tell they were our first forays into writing. We had good singles – [song publishers] April-Blackwood and Wally Ransom of Southern Music were very helpful and Russell Clark had this knack of picking the right songs. There was never a shortage of material.”

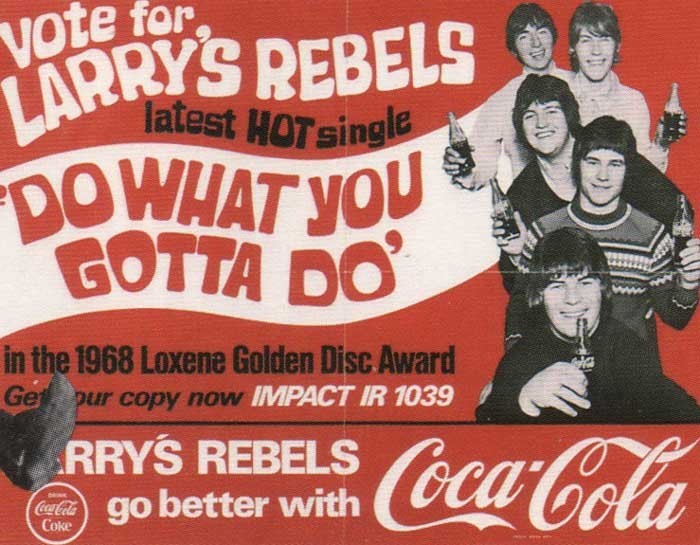

Larry’s Rebels returned from Australia and exploded back on to the local scene on the Loxene Golden Disc Tour. Their secret weapons were colour suits, Jimmy’s fuzz tone and the first strobe light on these shores.

An unused shot of Larry's Rebels from the same photoshoot as the Christmas EP. - Photo by Ian Baker

Were the suits the management’s idea?

“No. No, [Australian singer] Ronnie Burns took us to his tailor in Melbourne. Ronnie was the most astutely attired pop star I’d ever seen in my life. He wore these immaculate Edwardian coats with gorgeous satin shirts. We were regularly doing that Go TV show together on Saturday mornings. Ronnie was one of the hosts of that show. Ronnie took us to his tailor and I said, ‘We want suits like that’ – you know these little Edwardian things with three quarter drape type coats, very lovely with the double lapel and collar and everything, ‘and we’ll pick the cloth.’ We went to a haberdashery shop and picked the cloth. It just worked a treat. Women’s Weekly put us on the cover in those suits.

“We were the first NZ band to come home with a strobe light and that was an extremely big deal. It just blew people’s minds in 1967. When we got off the plane and no one knew we had all that gear and we had all those bright luminous suits. I can remember the suits like it was yesterday. We’d come on stage in the dark with the curtain closed. We had the strobe light, right up in the gods. We had Stan Rofe from 3UZ in Melbourne record the intro, ‘Would you please welcome the greatest attraction in the history of New Zealand show business! LARRY’S REBELS!’ It was typical Russell Clark. We started up with ‘Purple Haze’, so you’ve got the band playing a big ‘dom dom dom’ and the curtains would come up and the impact was just phenomenal. It was staggering, the first three shows we never got to the end of ‘Purple Haze’, the fire curtain would come down, there were people ripping us apart on the stage, there were cops and firemen everywhere. That was the Loxene Golden Disc tour and then they took us off of the tour.”

The Rebels spent a lot of time in Australia from 1966 to 1968. The two music communities almost merged for a few years, with New Zealand promoter Harry M. Miller operating successfully in both countries and NZ entrepreneurs Eldred Stebbing and Russell Clark achieving recording deals for their bands in Australia. The La De Da’s and Ray Columbus had hits on both sides of the Tasman. Many 60s NZ musicians like Max Merritt and the Meteors, Allison Durbin, Johnny Devlin, the La De Da’s and Dinah Lee made Australia their home. Larry’s Rebels had limited chart success across the Tasman, but toured extensively and recorded hits including ’Everybody’s Girl' in Australia.

Were the band’s trips to Australia a success or a disappointment?

“From [manager] Russell Clark’s point of view or a publicist’s point of view there was no trouble saying it was a success, but we didn’t feel that we’d succeeded. We didn’t have the support system over in Australia that we should have had as kids.

“Russell was there for the first few weeks and then he basically left us in the hands of strangers. We were all young, never been away from home before. Nicky Campbell, our roadie, who was the same age as me was looking after us.

“The Easybeats tour was a great way for us to kick off in Australia, that’s where I met a lot of guys who are still friends to this day. Brian Cadd I met on that tour, he was in the Groop and we’re mates, in touch every other day by email. We did the Easybeats tour and we did the Animals and the Yardbirds for Harry Miller.”

The Rebels’ first encounter with Australian rocker Billy Thorpe was not so positive.

“I met Billy Thorpe in Melbourne in 1966. We were doing a show with the Aztecs and they borrowed all our gear and blew the whole lot up. I nearly had a brawl with Billy that night, [then-Wild Cherry’s guitarist] Lobby Loyde got in between him and me and stopped it, but I was livid. I thought, ‘how dare you’. He was just so arrogant, an Australian giving a New Zealand band a run-up, and I got on his case. The Aztecs were a bloody great band. So loud.”

Blowing gear up is not a basis for friendship.

“It isn’t a good way to start but Max Merritt took us under his wing because Max Merritt and Ray Columbus were the generation before us. Word got around that, ‘these guys were reasonably good kids and they’re no trouble. That Larry’s a bit of humour, but he’s a nice bloke’. Then I became mates with the heavyweights of the industry, Glenn Shorrock, Ronnie Burns and Molly Meldrum, who was just starting out. We all used to congregate together in Toorak at the Winston Charles restaurant and nightclub. Billy and I became mates and went on a three-day binge together.

“We went through some sordid shit. Then I rekindled my friendship with him in Los Angeles and had some wonderful times with him in LA.”

The Rebels headlined their own nationwide New Zealand tour, Blast Off 68. Terry Rouse quit the band after the tour and Mal Logan replaced him. That same year, Morris and John Williams were finalists in the APRA Silver Scroll Awards for their composition ‘Dreamtime’. But on the Christmas Tour it was not only 1968 that came to a sudden end.

“I discovered there was no accommodation in Whitianga. ‘What the fuck’s going on?’

"One of the roadies said, ‘We’re all staying on the bus and we’re going back straight after the show.’ ‘Where’s Russell and Benny?’ ‘Oh, they’re in the local pub.’ So I went over there and they weren’t in the bar, so I looked around and was told, ‘they’ve checked in, they’ve got a suite here’. ‘Oh really?’ That really got up my nose big time. So I went up there and said, ‘unless you get accommodation for me and the band you won’t ever see me sing with the band again’. Russell said, ‘Yeah, right Larry.’ They never took me seriously. They didn’t and I left the band, and that was it. I regretted it all my life, because I think the Rebels could have been playing now. If we had stuck at it we could have become very, very wealthy and successful, and we’d be still recording now. Like Tim and Neil Finn are. But if I said something, l stuck to it. I was caught with my own personality, once I had said, ‘you do it or I’m going to leave the band,’ I was committed. Nobody believed me.

“The only one who really took me seriously was Dennis ‘Nooky’ Stott. I can remember Nooky saying to the others, ‘he’s gonna do it’. I went on stage and as we finished the last number I said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, l’m dreadfully sorry to have to say this but that is the last song I will ever sing with this band until the day I die. Thank you, good night.’ It was on the front page of the NZ Herald and that was it, I’ve never sung with them again.

Do you think the band could have survived because it was special?

“We would have survived, without a doubt, it was a very, very special band. I’ve seen it with Hello Sailor and earlier in my life I saw it with the Stones. I remember seeing the Stones the first time, and seeing Keith Richards tuning up Brian Jones’ guitar. He had one of those lovely pear-shaped guitars. I thought, ‘Christ, these guys aren’t all that together as musos if Keith’s got to tune Brian's guitar for him.’

“But those guys together were something fucking magical. And Hello Sailor were like that as a band. Early in their career they were average musicians, but put those four personalities together — Graham Brazier, Harry Lyon, Dave McArtney, Ricky Ball — and you had something very, very special. The Rebels were like that. We had this special thing because of the people — John Williams, Nooky Stott, Viv McCarthy, myself, Terry Rouse, and then later on Mal Logan, because Terry couldn’t handle it anymore emotionally. It got too much for him and he said, ‘ah screw this world’, and he got out of it.”

I thought your departure might have been because music was changing?

“No, nothing to do with that at all. It was all to do with Benny Levin and Russell Clark not getting us a hotel room in Whitianga. It’s the only reason I left the band. If you’re on the road with your major act who have made you a fucking fortune and if you can’t put us in a room and you can put yourself in one! That is the only reason I left the band. I could show you our original contract, they were getting 40 percent of everything we earned which was a massive amount of money they made from us. But no regrets [that] we signed the contract.”

Nooky Stott at Auckland’s Top 20 club.

In the 60s, nobody thought a band would last more than a year or two. Is that correct?

“No. We’d been together seven years when I left. We didn’t feel that. We started as youngsters, 15 or 16 year olds, John was 14. I’ve only had four bands in my life and I’ve been doing this 38 years.”

What Larry’s Rebels songs are you most proud of?

“‘Let’s Think of Something’ and ‘Everybody’s Girl’.”

The Rebels added Glyn Mason and released the hit single, ‘My Son John’, and the album Madrigal. In 1969, the Rebels moved to Melbourne and recorded a single, ‘Can You Make It On Your Own’. In January 1970, the group split and Logan and Mason stayed in Australia working in bands Chain and Home. Morris became a regular on the local cabaret circuit and a resident on TV shows C’mon and Happen Inn.

“I was on C’mon every week at 6pm for two years and then every week at 6pm for six months with Happen Inn. It was exactly the same show, the graphics changed to Happen Inn.”

It wasn’t drugs that got Morris thrown off TV, the first time. It was an apple.

“I threw an apple at Howard Morrison when he was live on Happen Inn, one of my best shots. I played softball for Point Chevalier, I could hit you in the chest with a softball. This was a rotten apple, but it was hard enough on one side. He started singing ‘Born Free’ and I turned to Shane and I said, ‘this has no place in this bloody show, this is a rock show. What’s going on? This is politics mate!’

“I grabbed this apple and hit Sir Howard in the chest and it exploded all over the place and I heard in the cans of the camera closest to me, ‘What was that? Who did that?’ As the apple hit him, I knew I’d done a stupid thing. l’d ruined my whole career. Howard was disgusted, he wanted to punch me so bad, but he just wasn’t up to it and I’m standing there, arrogant as fuck in my bloody yellow flowered suit, and Howard walked over and said, ‘That’s disgraceful!’ It was live on TV, there was nothing they could do. Director Kevan Moore came down in the commercial break, he had his hands on hips and said, ‘I want to know who did it.’ There was a real silence, and he said, ‘If I have to, I will fire everyone from this show.’ I thought well, in that case I’d better own up. I said, ‘It was me.’ ’YOU’RE FIRED, GET OUT! GET OUT.” It was amazing, he just went off, I’d never seen Kevan go off and I’ve talked to him since and he’s said, ‘l’ll never forget, I’ll take it to my grave, Larry.’” **

The next time Morris pissed TV off it was due to pot.

“They made a criminal out of me for a pot conviction, I know later on I got involved in a serious matter and went to jail for it. That’s not what I’m talking about. Kids have their lives fucked up because they’ve been busted with a couple of joints or a small bag of pot. The law is totally disproportionate and it’s wrong.”

When you went solo, was cabaret a good living?

“In 1970 I was getting $500 a show for 40 minutes. The money was extremely good but the quality of the music was crap when you had to work with a different band every night, New Plymouth this night, Rotorua that night. Eight out of nine bands didn’t have it in them to cut that stuff and it sounded like it. That’s why I did not like that work. I was very emphatic, I said to Russell Clark, ‘no, this is not for me’. And then they arseholed me because I got the pot conviction. Russell and Benny basically divorced me with a big right boot. They did not want to have anything to do with me.”

You did cultivate a bad boy image with Larry’s Rebels?

“No. My bad boy image was from my pot conviction. When I got in the shit. There’s two sides of show business, there’s the straight side, the Dave Dunninghams, Benny Levin, Phil Warren and they’re closet pissheads and get drunk and spew just like anyone else. Then there’s the outlaws. The moment I got that first pot conviction l became an outlaw. I joined [Tommy] Adderley, Ritchie Pickett, Marlene Tong and anybody else who’d had a pot conviction.”

They were conservative times. It is different today.

“You go and ask Simon Poelman [athlete jailed in 1998 for importing ecstasy tablets] about that. I don’t think so. You get tarred with that bloody brush. I’ve been in trouble once in my life. They locked me up for acid. That was in 1972, they released me in 1976 and I have never been back since.”

What is your best solo recording?

“The 5.55am album which Bruce Lynch produced. It was never released. l had just signed a great deal with John McCready at Phonogram Records and it all turned to custard when I got into trouble with the LSD conviction. When I got busted and taken to jail, Phonogram basically dropped me and the album was never released [by Phonogram*]. Barbara Doyle, who was managing me, went and bought all the stock and to this day she owns it and she gets $125 for each copy now. When I got out of prison I formed Shotgun, because I didn’t want to do that solo thing, I wanted to have a band again.”

When Shotgun met with little media or public interest, Morris headed for North America and spent the 80s in the USA.

“I made a lot of money, I was doing recording session work, Hollywood, Nashville, New York. Underground work. I was an illegal immigrant. They didn’t give me a visa to get in. I went through the bush from Canada illegally with a mate. There’s a network of people who knew me, John Farrar, Brian Cadd, Glenn Shorrock, Billy Thorpe, Max Merritt, they were all living in LA.”

While at a party at Renee Geyer’s apartment in Los Angeles with a who’s who of Australian music, even Olivia Newton-John, Morris got an unexpected tribute when the late Dragon singer Marc Hunter took the floor.

“‘Shut up! I’ve got an announcement I want to make! The reason I got into this music business. I want to draw your attention to a man here tonight. I saw a Larry’s Rebels gig in the Taumarunui High School Hall and I’d never seen a bunch of guys having so much fun, and when I saw all the girls hanging around after the gig, Todd and I went home from that concert with our minds made up, we were going to form a band.’ It was one of the most humbling things that has ever happened to me.

“And Mike Chunn says in his book Seven Voices, that Larry’s Rebels were the direct influence for him getting into the business. If we had a hand in bringing Dragon and people like Mike Chunn in to the business then we haven’t done all that bad as far as I’m concerned.”

In 1993, Larry Morris and his family returned from the USA, hoping to catch up with vocalist Tommy Adderley.

“He was still alive when we got on the plane but he was dead when we arrived.”

At the Gluepot fundraising concert, Morris performed with the recently defunct but funky Cairo, and they gelled so well, he has performed with them ever since as the Larry Morris Band. The repertoire extends from the Four Tops to Ben Harper, via War’s ‘Low Rider’ and The Sopranos’ theme tune. They will play a Rebels hit if requested but Morris is dismissive of Larry’s Rebels’ own songwriting.

“Our first forays into writing, you could tell they were our first forays into writing.”

When Jordan Luck recently took time to praise Larry about the “depth” of his lyrics for ‘Dreamtime’, as reproduced in Gordon Spittle’s book Counting the Beat, Morris replied: “I could say the same thing in a few words, now.”

--

*5.55am would see limited release on Barbara Doyle’s Gemini label in late 1971.

** Larry’s recollection, in Give It a Whirl, of this alleged incident was subject of a complaint to the Broadcasting Standards Authority in 2004, by former C’mon and Happen Inn producer Kevan Moore. The complaint was upheld; crucially Moore produced evidence that showed Morris and Morrison were never on either programme in the same episode.

© Murray Cammick

Larry’s Rebels reform at Auckland’s Real Groovy Records, 18 April 2015. - Photo by Carol Gillanders

–

Other pages about Larry Morris at AudioCulture

Larry’s Rebels part 1: Long Ago, Far Away

Larry’s Rebels part 2: Dream Time