Blink and Camp's most recognisable security guard Scruff (Camp A Low Hum 2008)

Talk to any indie musician in New Zealand over the past decade and you’re likely to find they’ve had some involvement with Ian Jorgensen (otherwise known as Blink), whether it’s playing one of his A Low Hum tours, appearing at his Camp/Campus A Low Hum festival, or playing at his Wellington bar, Puppies. Or maybe they were just in the audience at one of these shows or read some of his writing on his DIY approaches to touring and putting on shows. Either way, Jorgensen has been an inspirational figure for many and the motivating force behind hundreds of incredible live performances.

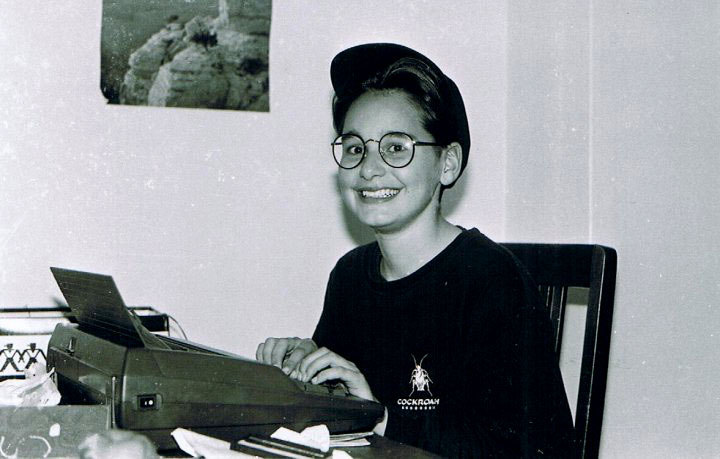

Blink at age 13, around the time he built his first dark room

Ian Jorgensen’s involvement in the local music scene came first through his photography.

Ian Jorgensen’s involvement in the local music scene came first through his photography. His sister and brother were both amateur photographers, so when Jorgensen formed his own band it seemed natural for him to take photos for them. His first band, at 13, was The Experience, which just did Hendrix covers. By the age of 17 he’d moved onto Red Hot Chili Peppers-inspired funk, then on to grunge and finally got into disco with Shep Ramsey and Truetones.

Blink running a tug of war (Camp A Low Hum 2008)

His friends at high school were skate photographers, some of whom went on to form Manual magazine, so Jorgensen picked up some of their tricks – using a slow flash synch and experimenting with the unusual colours produced by long exposures.

From the age of 14, he had his own dark room and spent long hours in the evening developing his prints. He soon became known for photographing bands around Wellington and took up the nickname “Blink”. When school ended, he took up a job at Camera House (a photographic studio), which gave him access to better equipment. He soon gained sufficient skills to support himself as a freelance photographer, shooting school balls and running fashion shoots.

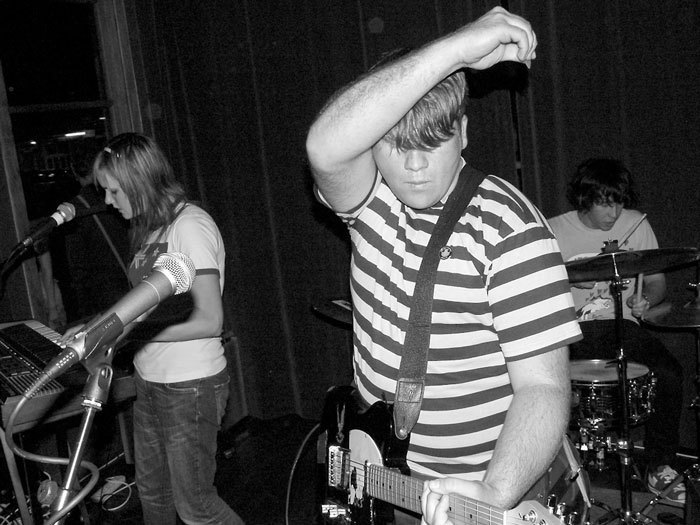

Cortina at Digger's Bar in Hamilton (A L0w Hum tour 2004)

A Low Hum - the zine

His subsequent decision to shoot most of his live music photography in black-and-white was influenced by a conversation with Liam Finn in 2001 – Finn argued that black-and-white photos had a more mythic quality, since they weren’t so tied to the reality of the moment and made the performer appear more distant and unobtainable. Many of Blink’s early photos were in Rip It Up, but they had less interest in black-and-white images, so he decided to start his own zine, A Low Hum. At first he wrote most of the articles himself, though he gradually gained more contributors. Later on, there was a regular column by Andrew Wilson of Die! Die! Die!.

Die! Die! Die! in the A Low Hum van

The early issues of the zine were packed with high-impact images – singers straining at the peak of a song, bands in motion, sweat shining on their faces, or atmospheric moments where the glare of the lights left only a hazy impression of a musician somewhere in the distance. When digital camera technology improved to a useful level, Blink made the switch and suddenly found himself with far lower overheads for his professional shoots.

Teenwolf at Sohl Bar Hamilton (A Low Hum tour 2005)

Touring bands

Blink was drawn further into the music scene when he received a call from Degrees K – a Christchurch band who were resident in Sydney, and who wanted to see if he could help them organise a tour of New Zealand (in October 2003). This seemed like good timing since it would coincide with the eighth issue of his zine, which he planned to release along with a CD compilation of local bands. The other act on the tour was Ejector, whom Blink had first met while they were still at high school – he photographed their school ball and they recognised him as the photographer who was always at the front of gigs. He helped them with tours and released their debut EP, as well as one by Ghostplane.

Ejector and Degrees K on the first A Low Hum tour

Blink hoped to use the tour to promote his zine, but Blink’s cunning plan for the release backfired. “I had this idea of releasing them in DVD boxes, with the zine slotted in where the information booklet usually goes. I bought a thousand DVD boxes cheap from Australia and then spent three days at the copy centre trying to resize the zine to fit them. But there wasn’t a way to do it without using a guillotine to trim each individual copy. I had a professional CD replicator so doing the CDs would’ve been easy and the tracks had already been mastered. I had tracks by The Phoenix Foundation, Phelps and Munro, and Sleeper’s Union, but I ran out of time, so I never ended up releasing it.”

The A Low Hum van

Further down the track, A Low Hum tours were sponsored by Jack Daniels, though Blink was initially suspect of their involvement with the music scene. The company had run a competition for a band to win an opening slot at the Big Day Out, which involved an online vote, but it seemed sure to go to a band that simply had lots of committed friends rather than a real support base. Blink jumped in with his own made-up band:

Blink keeping Mark Leong from So So Modern in line (A Low Hum tour 2006)

“I created the Fantastical Blink Band and ended up leading the competition, with support from the nzmusic.com community. The dude from Jack Daniels called me up, because he didn’t believe I’d go through with creating a band. But three days later, I pulled together a band and played a show. Eventually I decided that I would’ve been a complete dick to steal a slot off a real band and play at a festival that I’d criticised, so I pulled out. But through that process, the guys from Jack Daniels got to know more about me and asked me to come up to Auckland to present my ideas about promoting local music.”

Connan Mockasin (A Low Hum tour 2005)

The result was that Jack Daniels sponsored Blink’s early Low Hum Tours, effectively covering the cost of the zine and CD, so he could focus on getting the tours to break even. In return, he gave them a full-page ad on the back of each zine.

The aim of the tours was to grow an audience that wasn’t so dependent on which bands were playing on each occasion.

The tours aimed to grow an audience that wasn’t so dependent on which bands were playing on each occasion. It was also important to him that he try to organise a touring circuit that included Hamilton, Palmerston North, and Nelson – thereby helping to reach audiences outside the main centres.

Furthermore, he wanted to organise underage shows whenever possible, since the age limit at bars often meant that teenagers could only see bands when they played rare daytime, outdoor gigs. This meant Blink had to convince bars to open early so that he could have the bands play an all-ages set, with only non-alcoholic drinks for sale, before the main gig started.

The magazine might have started as a platform for his photography, but increasingly this goal gave way to the desire to promote local acts. So the articles became longer and the CD became a regular fixture (and he also gave exposure to local visual artists by purchasing poster art off them and then using this image as the cover for the concurrent issue of the magazine). At the end of 2004, he was awarded a bNet award for best compilation (though it wasn’t specified which of the 10 compilations he had released that year he was receiving the award for). He also ended that year by working with his first overseas act, Australian band Gerling.

Nick Johnston from Shaky Hands (they would later become Cut Off Your Hands) at A Low Hum showcase at Eden's bar, Auckland, 2006

It was an ambitious set of goals and initially, the scheme was just a very effective way to lose money. Blink went into debt with his girlfriend and parents to keep things going, working hard to cut costs where he could until the tours were as lean as possible. He scoffed at bands that said they were too poor to tour and yet who were quite happy cut into their show’s profits by spending it at the bar – though it was easy enough for him to criticise, since he didn’t drink at all.

Blink eventually realised that simply subsidising the tours from his fashion photography work wasn’t sustainable. “During the second year of the tours, in 2006, everything cost way more. I’d started doing two CDs and increased the size of the magazine. Plus I was doing proper sized tours by that stage – fifteen to twenty shows, with three bands on tour. I was even giving out per diems, which is fucking nuts! I was haemorrhaging money and so I got five months into the tours then realised I couldn’t continue like that. I was in Nelson in the midst of a tour and I saw that the Creative New Zealand funding round was closing so I grabbed one of my posters off a bollard and wrote on the back – ‘please I need money.’ I added my name and address, then sent it in. I knew the people up there were already aware of what I was doing and the money I was asking for wasn’t huge – I think I got 15 grand from them for the final six months of touring. It still didn’t cover all my losses, but it meant I could finish the year.”

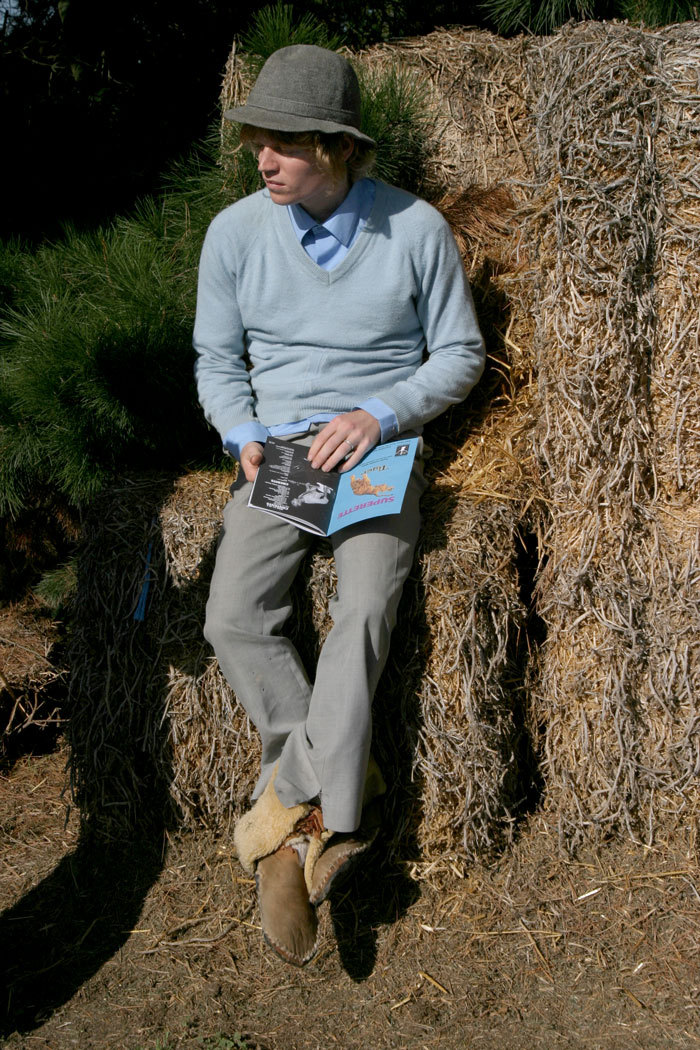

Connan Mockasin reading an early issue of A Low Hum

This cash injection allowed Blink to pay off his debts and purchase his own 12-seater van, so that he no longer had to hire one for each tour: “That year I bought a Transit van for around nine thousand dollars, which is the stupidest thing I ever did. It kept breaking down, so ended up continually having to pay for repairs on it. One month it broke down twice and cost me about three thousand dollars in repairs, and during that time I’d had to pay for rentals anyway so I could continue the tour. During the time I owned it, I easily would’ve spent another nine to ten thousand dollars on repairs or replacement van hire.”

Bands were asked to find their own accommodation or Blink would arrange sympathetic friends to offer up spare rooms and lounges. He arranged with the Interislander ferry that his bands would play a set during the crossing to pay for their journey.

“That was definitely a lifesaver for me, it saved me six hundred dollars every month since I had twelve people, a van, and a trailer. The band would have to play both ways and a lot of times that was kinda insane. During the football world cup, Mysterious Tapeman had to play and he really didn’t want to do it, but ended up walking over all the tables and no one knew how to take it. One of my favourites was The Sneaks, Thought Creature, and Cut Off Your Hands – everyone decided to play covers, mainly by guessing how the originals went. There was a busload of backpackers on board who all promised to come along to that night’s show, though I had to explain this was not what they were going to hear. They still came and it was the best show I ever had in Nelson. Another time, the Inkling played and this old couple complained about the noise. Then some other people yelled out – don’t turn down, turn up! So those two groups started arguing. Then another guy came over who was with a busload of people and he said they’d swap with the couple who were complaining so his group could hear the music better. So the band played on, but the old couple didn’t move – they just sat there with their backs to the band, with big pouts on their faces.”

Get Set Play (solo project of Mark Holland from Tiger Tones, in the centre) with Blink on the mic and Nick Harte (Shocking Pinks) on drums. At Camp A Low Hum 2007.

As time went on, Blink realised that the leg of the tour that was causing the biggest hold-ups was the return trip from Dunedin to Wellington, which involved trying to get the tour party up early on the morning after the gig, then driving for eight-and-a-half hours and catching the Interislander for two hours back to Wellington. Blink instead decided that he would simply pack the bands into the van straight after the Dunedin show and set off in the early hours of the morning, driving until dawn and beyond.

Within a couple of years, Blink had built up a supportive community of music lovers throughout the country.

Within a couple of years, Blink had built up a supportive community of music lovers throughout the country. “Looking back on it now, it’s great knowing how many people in the music scene now were just kids when I did those tours and came along to the all-ages shows. Particularly some of the shows in Christchurch, I’ve written before about one particular show at Creation in 2006 with So So Modern and Teenwolf, which had the same effect as that famous Sex Pistols show in the seventies, in the respect that practically everyone that was there went on to form a band. We sold out of everything that night and had to stay for an hour after the show burning CDRs on my laptop to fulfill the demand.”

This show included the young Christchurch band Black Market Art. Singer Darian Woods (also of Wet Wings) agrees that the show was pivotal. “We were just sixteen and played our take on the type of garage rock that was popular at the time. Until then we listened to bands on major labels or the local high school band playing Nirvana covers. The tour exposed us to exciting new independent bands that were alive and active in New Zealand, and – a little surprisingly – super friendly and humble. That show came with a (I think) DVD of underground music videos from bands like Golden Axe and Connan Mockasin, which widened our view of what was possible in New Zealand, and gave us a directory of like-minded musicians to see, play with, and collaborate with since.”

Bri from Frase + Bri, with Blink on drums (A Low Hum tour 2006)

As if inspiring the next generation of musicians wasn’t enough, Blink also did his part for some established musicians whose music hadn’t seen the light of day. In series three of A Low Hum magazine, he decided to accompany a number of the issues with a “lost album”. He unearthed unreleased recordings by no-longer-existent bands such as Xanadu, Dark Beaks, Dead Pan Rangers, Urban Tramper, and Dana Eclair (who went on to be Ghostplane). Blink began to realise that he could use the profile generated from the tours to re-energise his record label and experimented with having a “singles club” to put out new songs by his favourite acts.

Pool party at Camp A Low Hum 2007

Local Knowledge

In 2006, Blink gathered up the lessons he’d learnt about touring New Zealand into a book called Local Knowledge which he gave away free as a PDF on his website and sold at shows (charging little more than it cost to print). He hoped that the book would provide an easy source of information for young bands wanting to tour the country and that the information might gradually be updated online, though he now feels he could’ve done more to keep the tours alive.

“I didn’t create an infrastructure. As soon as I stopped doing those tours, the whole thing stopped. Bands like Rackets and Alazarin Lizard have done some great wide ranging tours, but it would’ve been great if there was more of a system in place. Writing Local Knowledge wasn’t enough, I really should have established more of a relationship between bars to support national tours after I stopped doing them ... The other trouble is that flights are so cheap now that it’s become less economical to drive, so bands don’t bother playing out of the main centres since there’s no motivation to do shows on the way to the bigger cities.”

His last year of arranging A Low Hum tours saw him working with US act, Yacht, and poised-for-success local act, Cut Off Your Hands. However it was his close friend, Disasteradio, who would undertake the final A Low Hum tour on local shores.

Over the four years that the A Low Hum tours had run, Blink helped push forward the careers of some of the most successful local indie acts, including Shocking Pinks, Connan and the Mockasins, Lawrence Arabia’s Reduction Agents, Die! Die! Die!, and The Phoenix Foundation. These were all bands that would go on to tour overseas and achieve audiences throughout the world. At the same time, Blink had become close to some of the acts and released their music on his label, becoming instrumental in the careers of The Enright House, Frase + Bri, Signer, Disasteradio, and Over the Atlantic (the new band of Nik Brinkman from Ejector). In four years, he completed 22 tours and took over 60 acts throughout the country.

Blink moved his focus to work on his new grand plan – a three-day event called Camp A Low Hum.

The A Low Hum tours came to an end in 2007, as Blink moved his focus to work on his new grand plan, a three-day event called Camp A Low Hum, that would take his no-nonsense approach to touring and apply it to running a music festival instead.

“It just started out as a party to celebrate the end of the tours, but more bands kept asking to play. I started to realise that it was becoming a festival. I’d never liked festivals myself, so I just tried to avoid all the things that I hated about them. So I made it BYO and allowed people to bring their own food, as well as trying to have proper flush toilets, showers and places to cook food. Then each band played twice so there were no clashes. I also wanted to run late at night so people could continue to party if they wanted or have the bands play in unusual places to add a bit of mystery to the event.”

Blink was not yet 30 years old when he first began working on his own music festival. His riskiest decisions were not seeking any form of sponsorship for the event and not announcing the line-up beforehand. He originally planned for the Low Hum tours to be unannounced in this way, but knew he hadn't developed enough of a reputation at that point to convince audiences to come along, whereas now there were many willing to trust that he would choose a great set of acts. The lack of line-up information meant that attendees would be coming to the festival for the overall experience rather than any particular act, though in the digital age it wasn’t too hard to gather a rough idea of acts that would be there by scanning Facebook pages and band websites.

The party van (Camp A Low Hum 2007)

Camp A Low Hum 2007

The first Camp A Low Hum was held on the weekend of February 3-5, 2007. The location was the Brookfields Outdoor Education Centre in Wainuiomata, just over a half-an-hour's drive northeast from Wellington. The location was surrounded by forest, but there was a large open field where a large stage was set up and an indoor hall, which was also fitted with a PA. There was also an outdoor swimming pool where DJs and MCs could do sets. There was even a small lagoon onsite and this created a scenic backdrop for US folksters, Polka Dot Dot Dot, who started their set by leading their audience on a parade around the campgrounds. The onsite van itself became a venue, with DJs pumping out music from speakers in the back and rapper Tommy Ill doing a set while hanging out of the back door.

Even before the music started, Blink was complimented on the relaxed party atmosphere. “The guys from The Sneaks came up to me on the first night, which was just meant to be for loading in, and they said, 'Dude, this is the best party ever!' I told them it hadn’t even started and they said it didn’t matter. It just had a good feeling. There were no comps, no VIP passes, no media passes so bands could relax and get drunk with everyone else who was there without thinking they’d have to do interviews or whatever. There was no real separation between an attendee and a performer – no green rooms, no backstage passes.”

Amongst the line-up were many of the bands that Blink had toured in the past – The Enright House, Ghostplane, Signer, Disasteradio, Frase+Bri, and Over the Atlantic – but he also brought in some other popular acts from Auckland – Liam Finn, Collapsing Cities, Kill Surf City, and The Sneaks. There were even a couple of acts from Australia – Actor/Model and The Rise & Demise – which showed Blink’s desire to create bridges to the scene across the Tasman.

It didn’t all go smoothly of course. Noise control arrived on the afternoon of the first full day and Blink spent the rest of the festival trying to reschedule acts so that they would only play inside after 11pm each night.

“It was basically just one house and there were a lot of people living closer who were fine with it. This couple called up noise control all day, every day. I kept going up there and I could hardly hear a thing, especially from inside their house. I told them – it’s only for a couple of days and your local community is making a lot of money from it – but they just wouldn’t hear it. Later they started a petition to never let me back there again!”

Liam Finn and Sam Scott at Camp A Low Hum 2008

Camp A Low Hum 2008

Blink made some slight adjustments to the 2008 Camp A Low Hum festival, held February 2-5 at Tatum Park in Ohau just south of Levin. This time only bands without much profile were given the opportunity to play twice (to give them the best chance of being seen) and he introduced more activities that weren’t music-related. He filled one room with cardboard boxes, sticky tape and markers so that participants could build their own protective outfits for “box wars” and arranged a short zombie movie to be filmed onsite.

This year also saw Blink introduce the Renegade Room for bands who weren’t officially on the program. “It was birthed the year before with Whipping Cats – I’d fucked up basically. The Coolies couldn’t play on Sunday, because they had to get back to Auckland, so I had to give them the Whipping Cats’ slot on the Saturday. Luckily I’d happened to give those guys the sickest cabin in the entire place, so they just asked if they could grab the gear after the loud stage closed and play a party in their cabin. That night, a whole bunch of bands who weren’t scheduled to play ended up playing. It was always my approach that I’d say yes to whatever people wanted to do, as long as it wasn’t going to hurt anyone. I was the facilitator of chaos really. So that Whipping Cats party really started the Renegade Room concept.”

The Whipping Cats' party in their cabin - it spawned the idea for the Renegade Room (Camp A Low Hum 2007)

The Renegade Room ended up seeing the only form of sponsorship that took place at Camp. A representative from Myspace wanted to sponsor an area of the festival, but Blink turned them down, although he left the door open for them to come along if they wished and put on a show in the Renegade Room just like a normal punter. This led to a performance by Bang Bang Eche in the Renegade Room that had hand-written posters saying “Myspace presents.”

Once again, he made an effort to bring over Australian bands and a few more made the trek – two members of Architecture in Helsinki did solo sets, and loop-maestro Pikelet also played. However, Blink’s biggest surprise from overseas was having US rockers Trans Am performing on the main stage. The camp was also a day longer than the previous year and this allowed time for a special event on the final night – a last night prom in the main hall, with an all-star covers band led by Liam Finn.

Box wars (Camp A Low Hum 2008)

It had only been running for two years, but Camp A Low Hum already felt like an institution on the local indie scene. But it wasn’t enough for Blink. The next few years would see him grow the festival, tour-manage/book another overseas tour, and start his own bar. He was just getting started on his herculean effort to push the local music scene forward.

Trivia

During one of the ferry ride shows during a Low Hum tour, Blink joined a jam band made up of members of Meestar and So So Modern (as bass player). On another occasion, Blink went up to do the PA announcement and found that the captain of the ferry was in total disbelief that the Phoenix Foundation were about to play on his boat (even more so, when they played a cover of 'Cruising on the Interislander' written by The Warratahs for a television ad in the eighties).

Edward Castelow (Degrees K/Dictaphone Blues) on the first A Low Hum tour: “I first met Blink when he came to photograph the band at Bodega, circa turn of the century. We were pretty fresh and in the big smoke so were naturally ecstatic when not only did a hip rock n' roll photographer come to check us out, but he also wasn't a dick when we met him. We started seeing him most times we went to Wellington and kept in touch when the band moved to Australia. A Low Hum had done half-a-dozen photocopied zine issues by the time our plans coincided in September 2003 - we wanted to tour NZ and Ian wanted to roll out the A Low Hum Zine/Tour/CD concept. Perfect. Plus he didn't mind me smoking spliffs out the window and I was partial to his seemingly bottomless bag of lollies. His van had been wired up with computer speakers for those travelling in the back, but these were still the days of the ‘10 second skip protection’ Discman, so the music came and went throughout the drive!”

Ian Jorgensen with A Low Hum CDs ready for the next tour ... - Photo by Gareth Shute

Links

–

Images courtesy of Ian Jorgensen, Petra-Jane Smith and Gareth Shute.