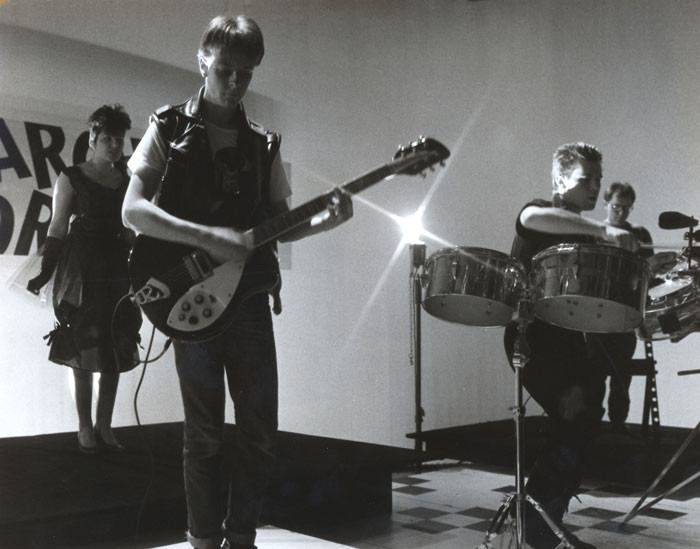

David Bulog and Nigel Russell from Car Crash Set

Andrew Schmidt traces the rise of electronic pop music in New Zealand and talks to Eric Roulston about electro-dance pioneers Ballare, the elegant Plans For A Building and synthesiser-based sounds in early 1980s Auckland.

Hit That Beat!

The roots of electronic sound run deep in New Zealand’s modern music. Contemporary classical composer Douglas Lilburn set up an electro-acoustic music centre in Wellington in the 1960s. Moogs and early synthesisers can be heard on New Zealand prog-rock records from the 1970s. Mi-Sex later successfully mined an Ultravox obsession for name and sound.

As always, the experimental quickly filtered through into popular music and the charts. Kraftwerk climbed to No.4 in New Zealand in May 1975 with the beguiling motorik of ‘Autobahn’, during a 14-week stay. The album Autobahn followed, climbing to No.7 in June and sticking around for 12 weeks.

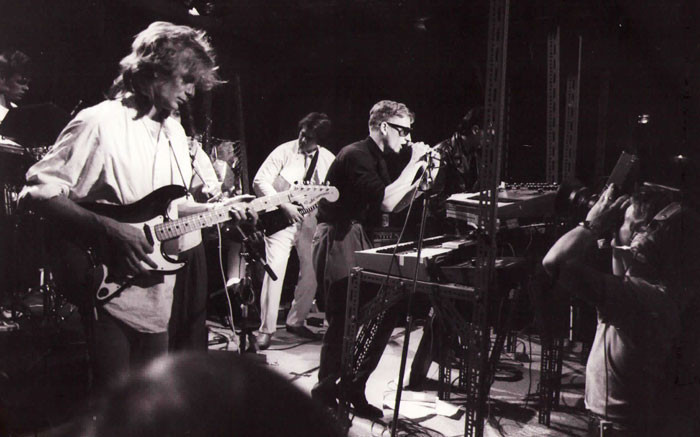

Ballare at Quay's nightclub: Eric Roulston and Jon Cooper

The influence of Neu! and Kraftwerk on David Bowie and Iggy Pop in the mid-1970s hadn’t gone unnoticed, indicating the place that percussive, keyboard driven German groups occupied in the critical soundscape of the early to mid-1970s.

Donna Summer’s Giorgio Moroder produced Euro-disco was a big hit in New Zealand, highlighting the radical and effective meld of R&B played through synthesisers that the Italian-born German based producer identified at the core of his sound. Well into the 1980s the Munich then Los Angeles based producer and songwriter was closely observed by fans of cutting edge sound.

The influence of studio and producer-centred dub on the musical times shouldn’t be underestimated either. Record catalogues and import ads show that the music was widely available in New Zealand in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Electronic sound pioneers aside, it was the new wave of performers emerging in the wake of punk who more clearly defined the sea change.

Electronic sound pioneers aside, it was the new wave of performers emerging in the wake of punk who more clearly defined the sea change. In October 1979, Gary Numan’s Tubeway Army had a No.8 hit with ‘Are Friends Electric?’. It spent a total of 20 weeks in the New Zealand Singles Chart.

The equally strong ‘Cars’ made No.18 in February 1980 and remained for 14 weeks in the chart. Numan’s Replicas did similar business, climbing to No.8.

The man himself was an early post-punk visitor to New Zealand shores in mid-May 1980 when he played shows at Auckland Town Hall and Majestic Theatre in Wellington.

Brian Eno, The Human League and Wire’s electronic sound based albums were hit records here in 1980. In mid-1981 Computer World returned Kraftwerk to the NZ album charts while Orchestral Manoeuvres in The Dark’s self-titled debut album sneaked into the Top 50. During 1981 Ultravox, OMD, The Human League, Joy Division, Depeche Mode, Heaven 17 and Visage all released compelling hit singles with synthesisers at the core of their sound.

Yet more albums and singles by Soft Cell, Heaven 17, Cabaret Voltaire, New Order, Depeche Mode, Yazoo and DAF arrived in 1982 to varying degrees of success. Rap, a new sound amalgam of the time, similarly utilised fresh technology and faced initial accusations of being non-musicianly were there as well. The record buying public clearly had few doubts about plugging into the new way.

When Ultravox arrived in late January for shows in Auckland and at the large Sweetwaters Festival south of the city, fans were able to see one of the new synth pop groups who were igniting the charts up close. Early February dates in Wellington and Christchurch followed and showcased the band at their Vienna era peak.

Simple Minds hit town next for two Auckland shows at Mainstreet on 18 and 19 October 1982. New Order followed, performing at the same venue in early December 1982, before moving on to Victoria University in Wellington. Dates listed for Christchurch’s Hillsborough on 1 and 2 of December never eventuated.

Despite the increasing popularity of the fresh sounds with music fans, the critical response in New Zealand was often dismissive, as was the reception from other strands of the fracturing post-punk movement. Local music writers used words like “sterility” and “lightweight pop” in describing the music and dismissed the genre as “not real”.

The sleek and progressive modernism of electronic based music clashed with the perceived earthiness and “authenticity” of guitar music, which is based in R&B and electric folk. Real music, it seemed, was made only by men with drums and guitars in smoky clubs and pubs.

The associated fashion was also derided as shallow and trendy despite the importance of fashion and anti-fashion to every pop music movement. The original punks were fashion conscious, a hangover from their days into glam, soul and Bowie, and a number of those early movers facilitated the new sound and environment.

The underlying appeal of the new music remained the same. The thrill of keeping an ear close to the zeitgeist was intact with new records such as The Normal’s ‘Warm Leatherette’ and Methods Of Dance compilations exciting those with a need for constant musical rejuvenation.

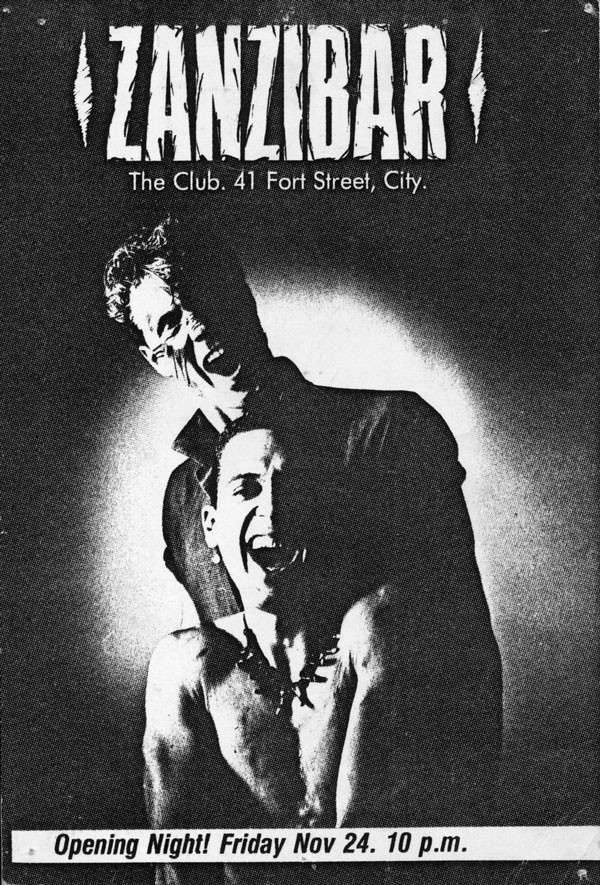

A conservative reaction similar to what had confronted the new fashion greeted the associated rise of new dance clubs like A Certain Bar, which opened on Thursday 5 May, 1982 on the first floor of the DB Tavern at the corner of Albert and Wellesley Streets in central Auckland. Pretty soon, specialist dance nights were happening at Buffalo Bar in Palmerston North’s Taverners’ Arms and Tony Peake’s Zanzibar in Christchurch.

A Certain Bar's Peter Urlich and Mark Phillips - Photo by Murray Cammick

A Certain Bar closed on Friday 26 August, 1983 and was replaced on the same site in October by PR, run by Patrick Waller and Rupert Taylor.

The new Quays nightclub, at 16 Quay Street behind the Auckland downtown bus terminal, pointed to a new era that cut deeper into the urban night by opening until 3am and effectively draining the punters away from pub-based early closers.

Danse Macabre

New Zealand’s creative response to the new sound arrived in earnest in late 1981 and 1982. Early post-punk group Danse Macabre included future Car Crash Set member Nigel Russell in their line-up and incorporated synthesisers effectively on their popular EP Between The Lines. It was a Top 20 hit for them in December 1981.

For those enamoured with the access principle of punk, electronic music held great hope and excitement.

For those enamoured with the access principle of punk, electronic music held great hope and excitement. Speaking to Mysterex in 2004, Nigel Russell explained. “I was interested in synthesisers and that aspect of sound making. My first synth was a Wasp manufactured in Britain. It didn’t have a keyboard. It had a touch strip. It had quite a fat sound and was capable of some pretty gnarly noises. The synthesiser was being pitched as egalitarian. An instrument for the people.”

In the final days of Danse Macabre, he spoke to Rip It Up. “People buy music by overseas bands without having the chance to see them,” he said, justifying the release of Danse Macabre’s mini LP Last Request after the group had split.

“They buy them for the music alone. I don’t see why it shouldn’t work that way in New Zealand.” Russell’s next musical project would involve “three or four keyboards augmented by percussion”.

It was no surprise then to find Nigel Russell at the vanguard of the new sound. Car Crash Set, the initially studio-only electro pop trio he formed in October 1982 with David Bulog and Nick Jenkins, featured on Propeller Records’ new band compilation, We’ll Do Our Best with the soaring, New Order inspired ‘Toys’. The strong electro pop contingent showcased by the May 1983 collection also included Ballare, Days Centrale, The Diehards and Terror Of Tiny Town.

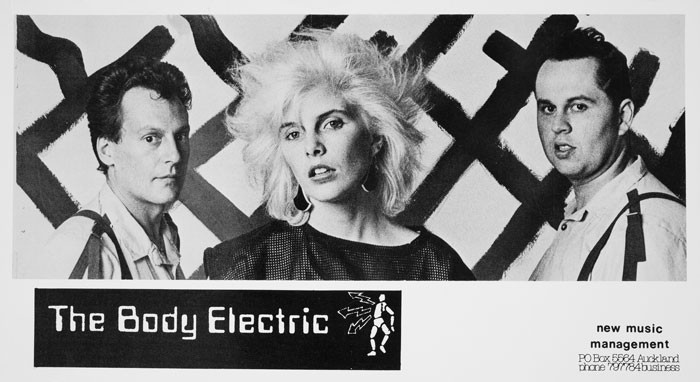

Body Electric Mk2: Alan Jansson, Wendy Calder and Garry Smith

New Zealand’s first electro-pop hit had arrived by then. The Body Electric’s ‘Pulsing’ began its 27 week run in the NZ Singles Chart in January 1983 and reached a peak at No.13 in April. Garry Smith, Alan Jansson and Andy Craig (replaced by Wendy Calder) followed the massive hit with ‘Dreaming In A Life’ (No.31) and the Presentation And Reality album in November 1983.

“It’s easy to take the facile route and slag this music on stylistic or inspirational grounds. Yet composition using technology takes a high degree of skill as it’s difficult to breathe life into artificially created sounds,” David Taylor wrote of the album in Rip It Up, indicating the broader critical environment in which the record was conceived and received.

The Body Electric’s Alan Jansson had already experimented with machine sound on The Steroids’ third single, ‘Shadows’.

Car Crash Set’s modest chart entry, Two Songs, produced by Trevor Reekie, the Reaction Records label boss and producer who soon joined the group, peaked at No.33 in July 1983. The topside, ‘Outsider’ is all economy and poise. Clean, uncluttered, linear, Modernist, propelled by a crisp dance floor beat and an insistent hook and electro drum barrage, the piece’s upbeat urgency works over the song’s entire six minute life.

This was music made for the urban dance floor. Song two, ‘Fall From Grace’ owed a debt to Neu! and New Order and doesn’t outstay its welcome at nearly seven minutes.

Which didn’t stop Rip It Up deeming the record “without tunes” after been similarly dismissive of ‘This Heaven’ by Marginal Era. A second Car Crash Set single pairing ‘Imagination’ with ‘Those Days’ appeared in November 1983.

More Auckland electro pop became available that year from The Diehards with ‘Rhythm Of The World’, produced by Peter Urlich and engineered by Tim Fields, b/w ‘Freedom’s Son’, produced by Nigel Russell. A second single, ‘Take My Hand (And I Will Lead You Away)’, was captured at Mandrill in July 1983 for the new indie label Hit Singles.

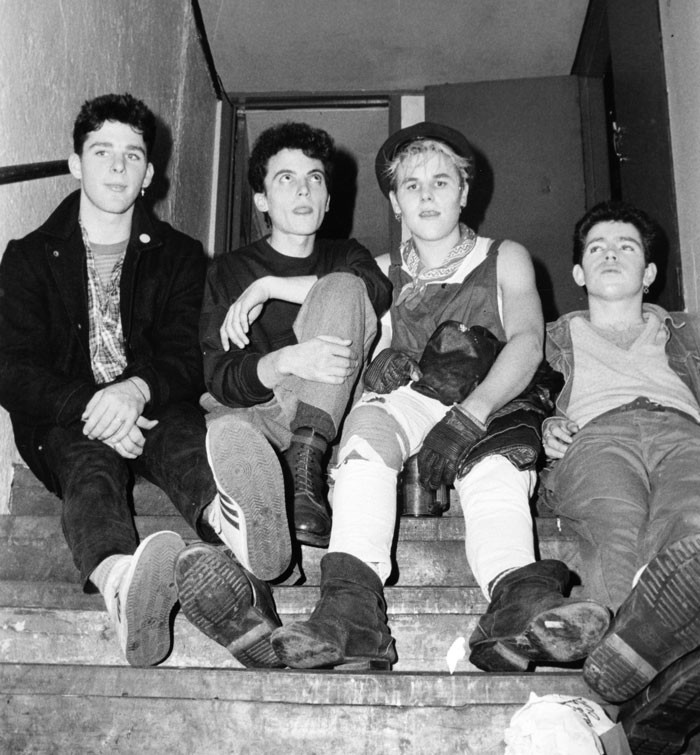

Terror of Tinytown, featuring Julian Hanson (from The Spelling Mistakes), Gary Grimes, Jero Dart and Matthew Stevens scraped into the pop chart at No.48 in November 1983 with ‘I Am The Need’ on Ze Discs.

Despite the centrality of the synth to the new sound and image and to the wider discourse around the music, few of the new bands were solely keyboard dominated.

Most of the new groups were signed to studio-based labels. Mandrill had Reaction Records while Harlequin sponsored Ze Discs, which reinforced and underlined the relationship with producers and cutting edge sound technology. Not that many of the rising groups lingered too long in the studio. The new electronic pop bands were quick to take their sound out to live audiences in 1983.

The Diehards

The Diehards’ Troy Mertz (synthesiser), Paul “Eddie” Edmond (vocals, guitar), Max Doyle (bass) and Stephen Eldson (drums) debuted in support of Rank & File in the last days of the Rumba Bar, played at Sweetwaters in January 1983, then toured in front of Dance Exponents on a 21 date national tour in April and May 1983.

The young quartet, most of who were in their late teens, played out regularly that year at Auckland’s Windsor Castle, before touring New Zealand’s provincial cities in their own right in September. The departure of Elsdon saw Yoh (Laurence Landwer-Johan) from The Screaming Meemees take the drum stool for The Diehards’ support slot to The Mockers at Mainstreet and for weekends in Gisborne and Mount Maunganui in October. Two nights at New Plymouth’s White Hart in December followed.

With talk of a worldwide record deal with RCA Victor Records, a new EP coming, and a debut album about to be recorded, the future looked bright indeed for The Diehards.

Marginal Era already had ‘This Heaven’ in shops when they packed the van in August with new member Richard Newcomb, who replaced Phil McDonald. Newcomb joined Paul Agar, David Mauger and Dave Larsen on the North Island and Christchurch tour that pushed through into September. Larsen would soon be replaced by Daron Johns, late of This Sporting Life.

Still reluctant to perform live, Car Crash Set planned to “self destruct” onstage at Mix It Up in Auckland’s Mainstreet on 12 October 1983. The group’s debut live show proved instead to be the first of two shows that year with Peter Urlich and Mark Phillips's succesor to A Certain Bar, Zanzibar, in Fort Street, hosting the Auckland electro pop act on December 22.

Car Crash Set at Zanzibar

Arguably the biggest act from New Zealand synth pop’s arrival, The Body Electric kicked off 1983 with the comprehensive Pulsing With Punch summer tour, with The Spines. Starting in February and taking in 18 cities and towns, the mismatched pair finished the tour at Auckland’s Mainstreet and A Certain Bar (where else?) in mid-March.

The popular tour kicked off a surge of Body Electric shows that left few of New Zealand’s live rooms untouched in 1983 and 1984. In doing so The Body Electric made a lie of the new sound’s lack of live stage appeal and prowess. There were multi-night stands at Wellington’s Cricketers, Auckland’s Windsor Castle, De Bretts and The Gluepot and Hamilton’s Hillcrest and Metropole, and a Body Electric live show was recorded for Radio With Pictures at Wellington’s Majestic Theatre in 1983.

It shouldn’t have been a surprise when Alastair Riddell first resurfaced in 1982 with his new band Modern Contours and an electronic pop album, Positive Action. He is after all the closest New Zealand has to a David Bowie. A North Island tour in late 1982 and January 1983 and shows at Auckland’s Windsor Castle in March introduced Riddell to a new generation of fans.

More surprising was the rise of electro pop groups from the North Island’s provincial centres. From Gisborne, Marching Orders (Tony Murdoch, Russell Braithwaite, Jackie Clarke and Martin Kirk) made a splash at the otherwise tepid Shazam Battle of the Bands in August 1983. Down the road in Hamilton, Step Chant Unit (Neville Sergent, Brian Brighting, Sue Thoms and Zed Brookes) were also making synth-based music. They took it through the country in July, further indicating the new sound’s wide national appeal.

Step Chant Unit

Having established an undeniable chart and live presence in 1983, New Zealand’s electronic pop groups opened the throttle in 1984. The Diehards performed at Auckland’s Mon Desir in late January and Hamilton’s Hillcrest in mid-February ahead of the March 1984 release of ‘Hit That Beat!’. It was the third time the song had been released by the band.

The latest version appeared on RCA Victor and featured Michael O’Neill on guitar, Keith Ballentyne on trumpet and Graeme Myhre, an engineer and producer who became closely associated with the electronic pop sound in New Zealand.

In April 1984, The Body Electric based themselves in Auckland. On the recording front, things remained promising with ‘Imagination’ making the Top 30. An Ian Morris remix of flipside ‘Zanzibar’ was mooted for release in England and a limited dance and electro remix of ‘Pulsing’ was also made available.

Peter Urlich and Mark Phillips on the opening invite to Zanzbar

A New Zealand tour taking in Hamilton, Napier, Gisborne and Mount Maunganui, and multiple live events in Auckland at Mainstreet, The Venue and Zanzibar soon followed. The electronic trio then headed further south in May for shows in Queenstown, Invercargill, Alexandra, Dunedin, Christchurch, Wellington, Masterton, Wanganui and New Plymouth. Yet another mini-tour of the Auckland region (The Mon Desir, White Horse, Zanzibar, The Gluepot, The Forge, Onerahi and Waiuku) closed out May and brought in June.

Marching Orders

Gisborne’s Marching Orders picked up steam in 1983 with shows at The Venue in Auckland alongside Katango and gigs at The Cricketers in Wellington. The untypical release of ‘The Dancer’, taped at Mandrill in September 1983 and released through Flying Nun Records in late 1983, heralded shows in Wanganui, New Plymouth, Palmerston North, Wellington, Auckland and Whangarei in June and July.

It was a busy year for Marginal Era as well. The Trevor Reekie and Glyn Tucker produced ‘You Fascinate’, a No.38 hit in July 1984, was chased by a run of shows at The Gluepot with Car Crash Set. A night at Zanzibar and a belated release party at Quays followed in mid-June.

After a three-night run for the group at Hamilton’s Hillcrest and two dates at The Venue, Marginal Era’s second single of the year, ‘Haven’t I Seen Your Face’, hit record stores in September. A mid-month Zanzibar night and double bill with Car Crash Set at Quays echoed June’s schedule.

Marginal Era

That was before Paul Agar decided to jump ship in November and head to Melbourne for a solo career. Marginal Era’s remaining members tried to carry on with The Grammar Boys’ Simon Alexander as This Heaven, a name utilising the song title of the well-known instrumental from their first single that now ran as the intro theme on Radio With Pictures.

And what of Car Crash Set? They were playing out more frequently. Live performances at Zanzibar on 18 April 1984 and Windsor Castle on 24 October 1984 bookmarked a productive mid-year for the band. ‘Breakdown’ had appeared in September and the bulk of their debut album No Accident was recorded between March and August.

Katango

A single coupling the album’s title track and ‘Sax Appeal’ announced the arrival of CCS’s debut album in November. In an interview with Rip It Up, Dave Bulog denied that Car Crash Set was a synthesiser band. Elements of funk were now present. There was one last show that year, at Zanzibar on New Year’s Eve.

New Zealand’s interest in electronic pop music didn’t end there. The sound was a chart and live staple well into the 1990s.

New Zealand’s interest in electronic pop music didn’t end there. The sound was a chart and live staple well into the 1990s. Overseas synth pop groups continued to tour New Zealand successfully. 1984’s Sweetwaters had Simple Minds and Eurythmics on the bill. The Fixx arrived in July 1984. New Order visited the shaky isles in May 1985 and Tears For Fears in August. Simple Minds were back in November 1986 for three events, including a huge Western Springs show. OMD added Hamilton’s Founders Theatre to their December 1986 New Zealand tour.

Along the way there were some truly startling records from New Zealand acts. The Mockers, with Tim Wedde on keyboards, had a strong electronic sound, as did a lot of younger NZ pop acts. It’s worth noting that the topside of The Mockers’ first single ‘Good Old Days’ from October 1980 had the electronic sound down early. Shona Laing in particular utilised the new technology to fine ends on the brilliant ‘(Glad I’m) Not A Kennedy’ and South, but she was one of many.

By then, the knocks had been taken and the prejudices made a lie. The only truly modern music movement of the 1980s was now a permanent part of the pop terrain.

--

Ballare

Ballare’s infectious ‘Dancing’ from 1982 had a hard electronic groove, a strong experimental edge that bubbled over two thirds of the way through and its eye fixed firmly on the dancefloor, on what could well be New Zealand’s first fully synthesised dance track.

Andrew Schmidt talks to key member Eric Roulston about Ballare’s early days, utilising the new sound technology and his next group, Plans For A Building.

What were the inspirations, both local and international, for getting Ballare together?

“Just the whole post-punk scene where things were really happening locally and New Order/ Joy Division and Human League were doing amazing things with electronics. Jon [Cooper] was a drummer and I was a bass player by experience, but we wanted to add a new dimension. Our influences were very similar. We both loved dance music as well as bands like Roxy Music and Bowie.”

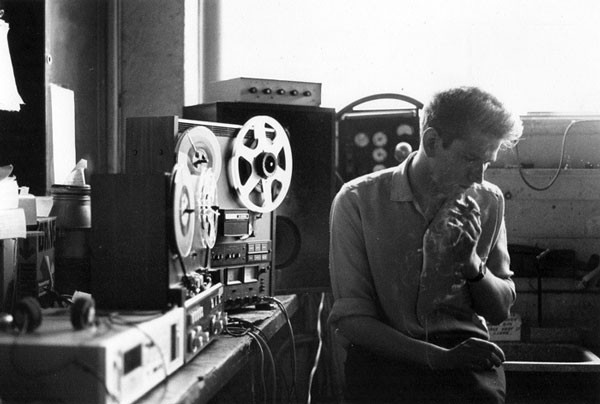

Jon Cooper - Eric Roulston collection

Can you describe the Auckland music scene as you saw it, before and after Ballare formed?

“The scene was full of fantastic punk pop bands. I had been close to The Screaming Meemees and The Ainsworths. The live club scene was on fire with great pop songs with a twist. There was limited electronic music. Danse Macabre was being relatively innovative, but we were the first totally electronic pop group to emerge. We formed a very cool cult following and later bands like Car Crash Set and The Body Electric came out.

Propeller Records’ Simon Grigg mentions The Screaming Meemees as an inspiration and describes you as “post-Zwines punks”.

“Ah Zwines. My background was kind of odd as I was also into club music pre punk. I enjoyed The Commodores, Slave and Rose Royce, before they were cool. I used to pile into a car with ten other mates and drive to Auckland all the way from Papatoetoe and go to Odyssey nightclub and others in Parnell.

“I studied piano and played bad bass. When the electric scene came out it just cemented my direction. Early inspiration came from Giorgio Moroder and the Euro Disco scene.

“My turning to electronic and punk came when I was at an open air concert and Th’ Dudes played. ‘Walking In Light’ was stunning. My first three concerts had been Little Feat, The Commodores and David Bowie, so my tastes were very eclectic. The name Ballare obviously is Spanish for dance, but I took it from a song by Kleeer called ‘I Love To Dance’.”

What music were you listening to? What did you consider important before and after Ballare formed?

“My influences are wide and varied from The Beatles to Genesis and Peter Gabriel and Bowie’s Low for many years. Then the whole electronic scene exploded. Depeche Mode, Human League etc, not forgetting Chic and many early funk outfits.”

Eric Roulston and Maria Majsa from Ballare - Eric Roulston collection

Fashion is an important part of the era. Who was influencing you there? Where did you get your clothes?

“My introduction to the Auckland music scene really came from fashion. I was doing the music for a fashion show. I could play bass and had bought some cheap synths. I had recruited Peter Van Der Fluit from The Screaming Meemees and Adam Holt from The Ainsworths to help me perform it although it never eventuated.

“I was making all my own clothes, very new romantic, and wore eyeliner, foundation and even lipstick, baggy jodhpur pants and laced up baggy shirts.”

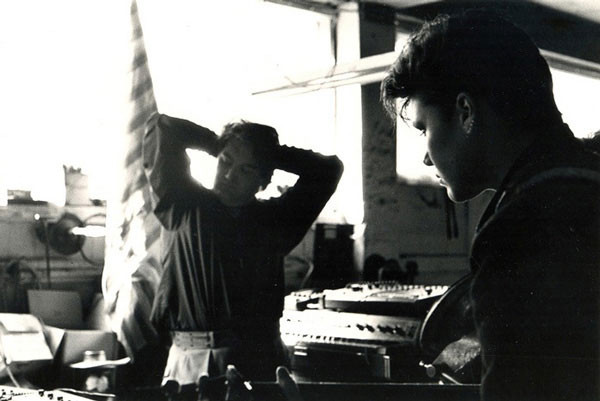

‘Dancing’ is a fantastic song and given its vintage, an important one in the history of electronic music in New Zealand. Who plays on the song and what did they contribute?

“Jon [Cooper] and I were always at a place called Last Laugh Studios, so much so, that Jon eventually began working there! We would go in there from midnight to dawn and muck around.

“Jon was very much into the technology whereas I was into sound. We did thousands of tracks, but only a few ever got finished. Neither of us was interested in being the front (or had the nerve or talent to) of the band so we auditioned Janine Grey as our singer, and later Maria Majsa on guitar.

Ballare's Janine Gray - Eric Roulston collection

What equipment was used and how was it sourced? Can you remember the approximate price of the gear?

“I had an old Korg string machine that used to lock up as a suitcase. That was my first. Then I invested in a Korg Polysix and a Roland TR-808. The equipment cost so much and was always purchased on hire purchase and as soon as you would pay it off it was redundant. But then equipment was moving so fast technology wise.

“Midi was just launched and all the old equipment was being superseded. I really loved the old synth sounds. I looked at the digital stuff, but never bought them. I loved the fat sound and the raw of analogue. Jon had a MS20 mono synth, and a Poly 8 synth was the same price they are now, give or take.”

Did you take the music into a live or club setting? If so, where, and what was the reaction?

“We did a lot of live work at clubs and universities mainly. They went well, but already in the early days, most were waiting for ‘Dancing’ to launch. We did a lot of covers as well of songs like ‘Both Ends Burning’ by Roxy Music.

When did Ballare stop and why? Where did the members go? Are there any other recordings in existence?

“I can’t remember why we stopped. I think there was a girl versus boy thing and Jon and I ended up auditioning for a new singer, but we both fell into new projects. Jon into studio work, and me, into Plans For A Building.

Plans For A Building

What were the inspirations both local and international for Plans For A Building? The group has more of a traditional form than Ballare. Why the move from strictly electronic sound?

“I auditioned for PFB and fell in with singer Tom Pound and thought this would work really well. The early line up was Robert Mayo (IQU) on drums, Tom Pound (vocals), Pat Pound (guitars), Phil Bishop on bass and me.”

What music were you listening to? What did you consider important before and after Plans For A Building formed?

“We were very much inspired by artists such as The Cure, Simple Minds and The Associates. There were splinters here. Tom and I used to perform poetry to ambient music at parties or anywhere. Phil and I would spend days in our flat in Parnell writing the music. We were offered a record deal with Hit Singles where we made ‘Some Alter Some Sacrifice’.”

‘Some Alter, Some Sacrifice’ on Hit Singles leaped to No.14 in the pop charts on 24 August 1984 then dropped out the next week.

“Tom did all the work with the label and Hit Singles. Tom’s lyrics were always dark, but the main theme was about change. The artwork was done by Pat Pound. As part of our live shows to promote the single, the record was included as part of the door fee, which was then logged by the label as a sale, hence the sudden rise and demise.

“There were some issues out of the release with Phil and I versus rest of the band. After we did the final mix, Tom and his bother Pat went back and remixed without us knowing about it. In the end, I was very disappointed in the final release.

“We disbanded, but I was still working with Tom and we ended up working with Weston Prince and Roddy Carlson from Danse Macabre. We then reformed PFB and wrote ‘All of a Life’. I invited Peter Van Der Fluit to come down and play bass. Out of these sessions we were creating some wonderful sounds.”

There’s a video clip for ‘All Of A Life’ – fantastic song again – but I can’t find any record of it in discographies? Was it released?

‘The video for ‘All Of A Life’ came from a grant for an independent producer, so we all caught the train down to Wellington, and recorded the video in one day, then came home again from Avalon Studios.

“It was shown on Radio With Pictures, which is where I edited the clip from my old video collection to put up on YouTube. The line-up was as above although Peter Van Der Fluit had other commitments so Jon Cooper (from Ballare) mimed the bass in the video. Jon was also our producer.

“We were offered a record deal and were going to go into a proper studio to re-record all these tracks. It fell through. Disillusioned, I decided I was going to pack up and head to Australia.”

How often did the group play out? Did they venture out of Auckland?

“We played live, but it was mostly in a splinter form. As a band we did some great gigs, hired venues and multi-billed events with other local artists. We did a final show at Quays nightclub, which was fantastic. The line-up was Keith Pinney (guitars, bass), Robert Mayo (drums), Peter Van Der Fluit (bass, percussion), Carl Stuck (percussion) and Tom Pound and I (vocals).

“I loved it as I was able to use the state of the art synths lent to me by Paul Crowther (ex-Split Enz), not much to many, but a highlight for me. I was able to use the Emulator and Oberheim gear!”

When did PFAB split?

“PFB split when I hopped on the plane to Oz in 1986. Roddy Carlson joined me and using the works of PFB, we were offered a contract in Australia. Mushroom would be the distributor and Factory the label, but we couldn’t get the rest to make the move over. So that eventually fell through when Roddy moved to the UK.

“I was working at the time as a programmer for a guy who owned a Fairlight and I began to become disillusioned. In 1988, I gave it away, sold everything and moved to the UK with my wife Sophie, and never played again until ...”

You have The Association project at present and are based in Sydney.

“A few years ago I inherited a few thousand dollars and set myself up in a home studio. I have several digital labels releasing my work, predominately ambient film music. I also do a lot of retro remixes and have just set up my DJ set up (out come the old disco records and 1980s vinyl collection).

“I do miss playing in a band though. The original concept of The Association was exactly that. Working with many other artists, and having huge fun working with people in the United States and United Kingdom.”

--