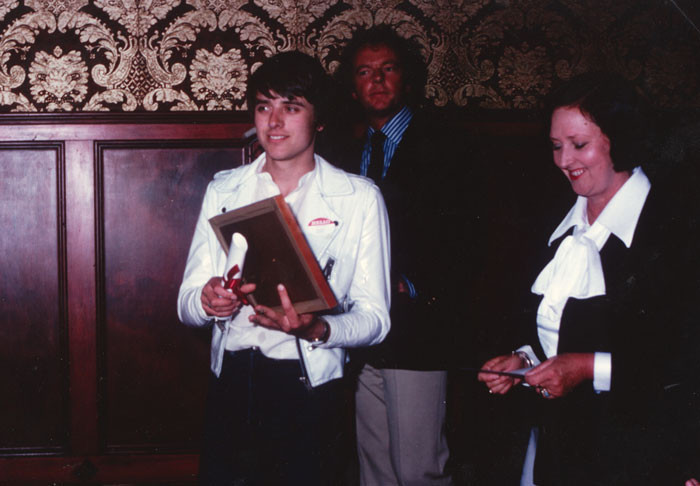

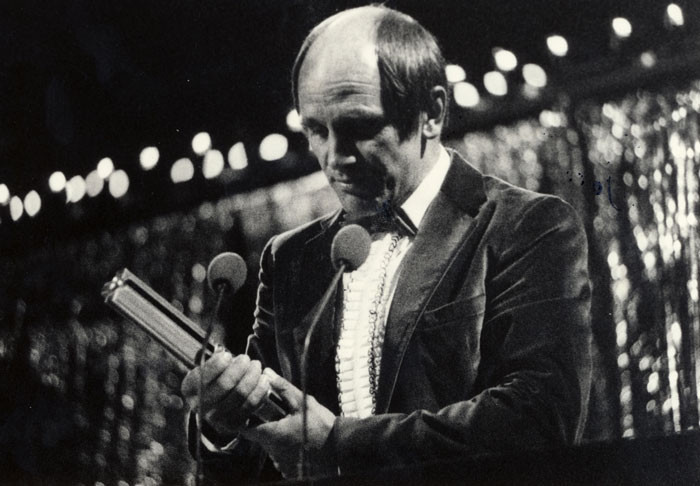

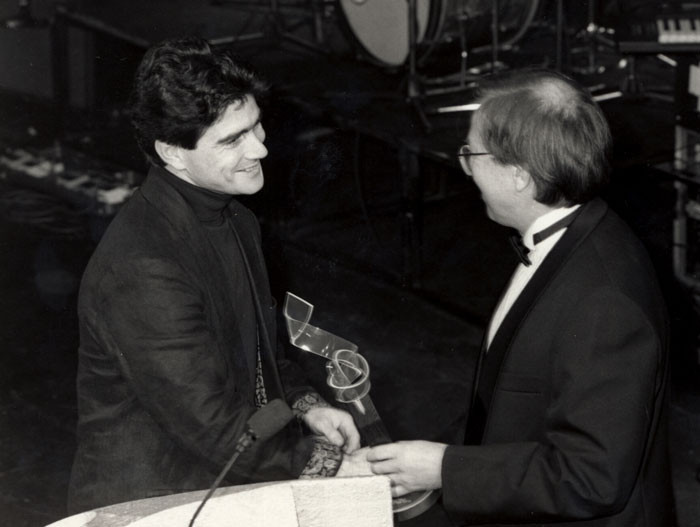

Dave Dobbyn and the then Leader of the Opposition, David Lange, 1983

Music Awards are, by their very nature, high-profile affairs that everyone has an opinion on. Too glitzy, not glitzy enough, too diverse, not enough diversity, far too many categories, should be more categories … and on it goes. A walk through the history of the NZ Music Awards certainly reflects the changing tastes – and budgets – of the local recorded music industry across the decades.

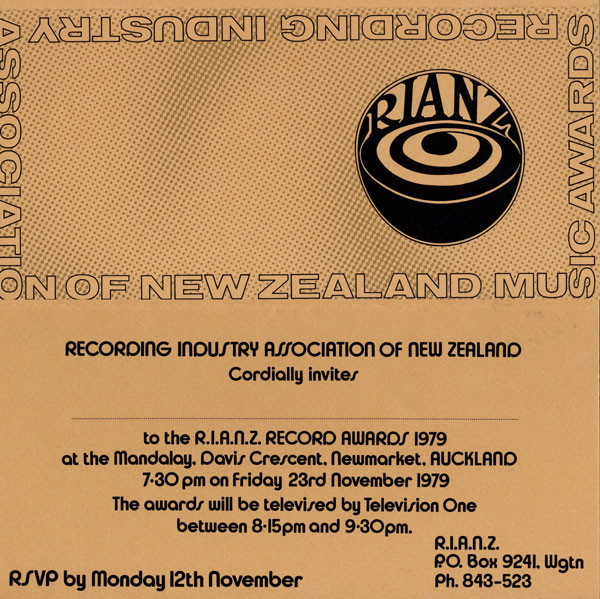

The RATA era 1973-1976

Eight years after the inception of a national music award (the Loxene Golden Disc), the first of many evolutionary changes were in the air. Rumblings from various labels, particularly independents, about how the Golden Disc was run and, more specifically, the cost of providing cripplingly expensive amounts of promotional product (432 single-play records and 16 photos per disc and artist entered) demanded a new structure. The industry’s representative body, the NZ Federation of Phonographic Industries (NZFPI), had been involved in the Golden Disc committee, but now took a controlling hand, instituting a new structure and renaming it the Recording Arts Talent Award (RATA).

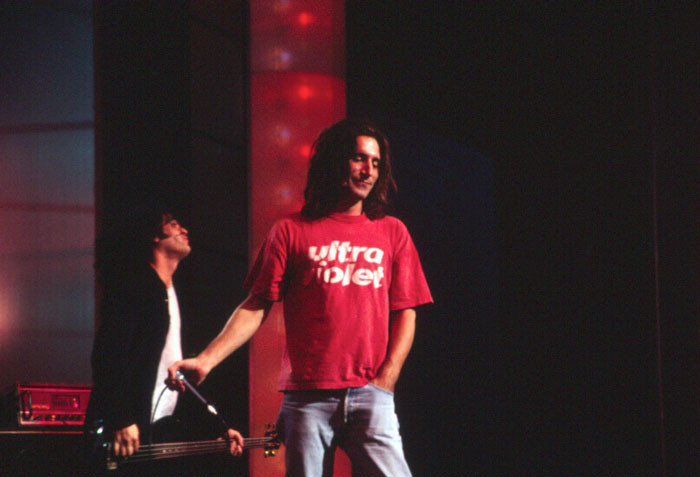

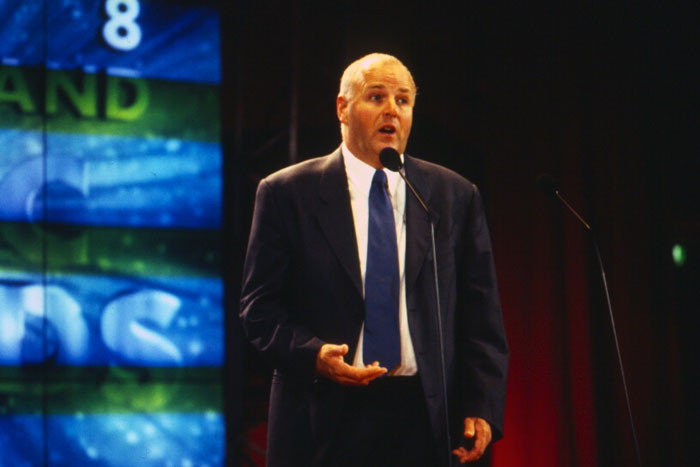

Jordan Luck, 2002

Ian Morris, 1977

Moana Maniapoto, 1999

Julia Deans and Lani Purkis, 2008

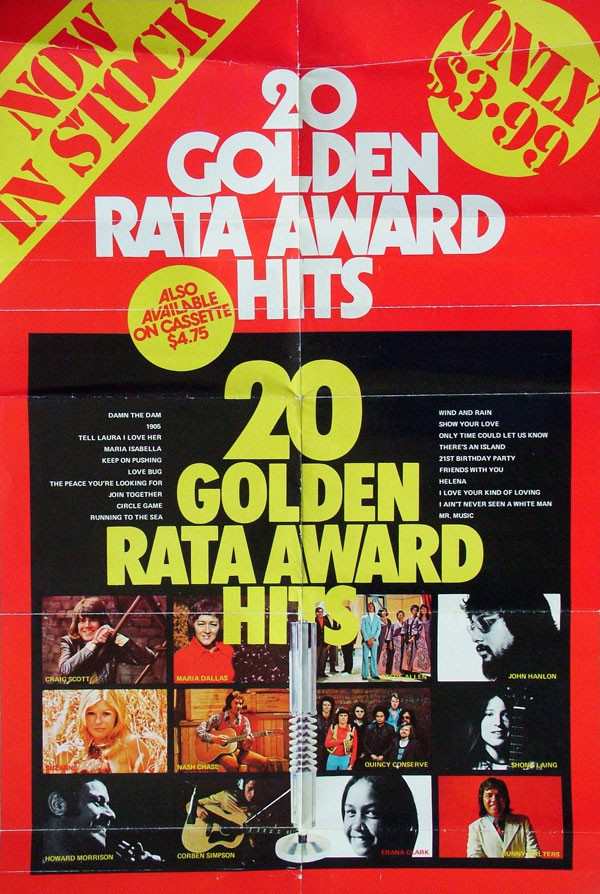

Whereas the Golden Disc focused solely on singles, the RATA award expanded its brief to include albums, performers, producers and engineers – 11 categories in total. A decade later that number had nearly doubled to 20, and the current awards format now recognises 30 categories.

The first RATA award was made of four interlinking parts which screwed together to form a 40cm-tall gold staff, and the ceremony itself was in two interlinking parts: a pre-function at the cliff-top White Heron Hotel in Parnell, followed by the presentations themselves at Trillo’s in downtown Auckland. The White Heron has now been demolished to make way for luxury apartments, whilst Trillo’s gave way to the Downtown Shopping Mall – its once upmarket interiors now home to the less salubrious décor of The Warehouse and various franchise food outlets.

Sharon O'Neill, 1984

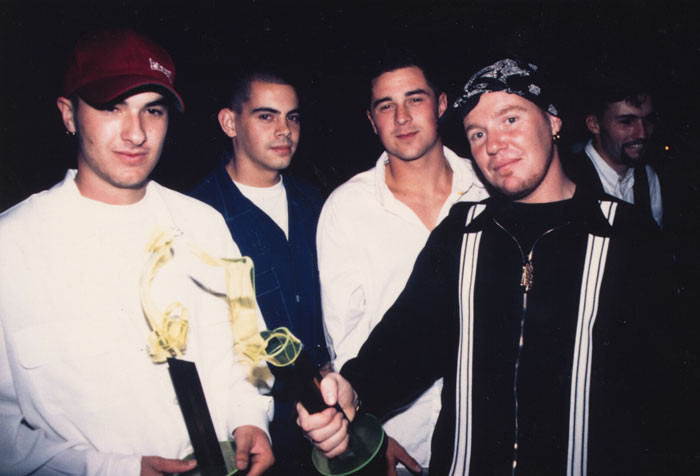

Urban Disturbance (with Zane Lowe on the left) and Matty J, 1994

Zed, 2001

Haley Westenra and Dave Dobbyn, 2001

The Topp Twins

Four years into the RATAs, a downturn in the economy saw record companies feeling the pinch resulting in plans for a 1977 show being shelved. With that, 1976 became the last official year of the RATA awards. The awards would bounce back under a new name and new administration.

1973

Album of The Year: John Donoghue – Spirit Of Pelorus Jack (Ode)

Single Of The Year: John Hanlon – 'Damn The Dam' (Family/Pye)

Producer Of The Year: Keith Southern for Steve Allen's 'Join Together' (Viking)

1974

Album of The Year: not awarded

Single Of The Year: John Hanlon – 'Is It Natural' (Family/Pye)

Producer Of The Year: Mike Harvey for John Hanlon's 'Is It Natural' (Family/Pye)

1975

Album of The Year: John Hanlon – Higher Trails (Family/Pye)

Single Of The Year: Rockinghorse – 'Through The Southern Moonlight' (EMI)

Producer Of The Year: Alan Galbraith for Mark Williams' 'Yesterday Was Just The Beginning Of My Life' (EMI)

1976

Album of The Year: New Zealand Symphony Orchestra - Symphony #2 (EMI)

Single Of The Year: not awarded

Producer Of The Year: Alan Galbraith for Mark Williams' 'Taking It All In Stride' (EMI)

RIANZ and the New Zealand Music Awards

The financial pressure and political disruption that record companies experienced at the tail end of the seventies saw a reorganisation of the companies’ representative bodies. The NZFPI, which had been in existence since 1956, was to become Phonographic Performances NZ (PPNZ) and its focus to be on the copyright and licensing side of the business. A newly formed subsidiary, the Recording Industry Association of NZ (RIANZ) was formed in 1978 to have a separate focus on industry promotion and, importantly, lobbying the Government and Opposition in regards to the crippling sales taxes imposed upon record companies.

He was still a Shazam host at the time, a young Phillip Schofield in 1984

John Tamihere and a representative from the Rangitea Concert Party, which won Best Mana Māori album in 2002

Andrew Fagan, 1984

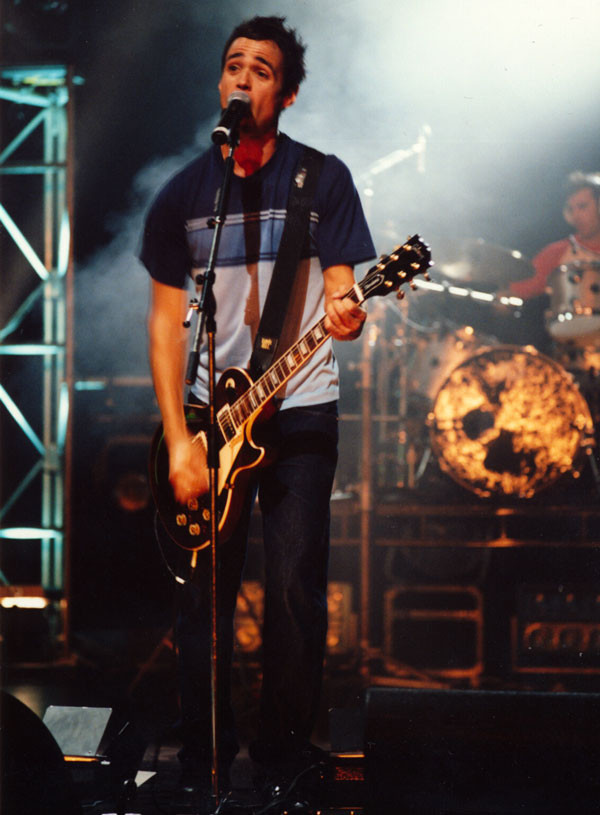

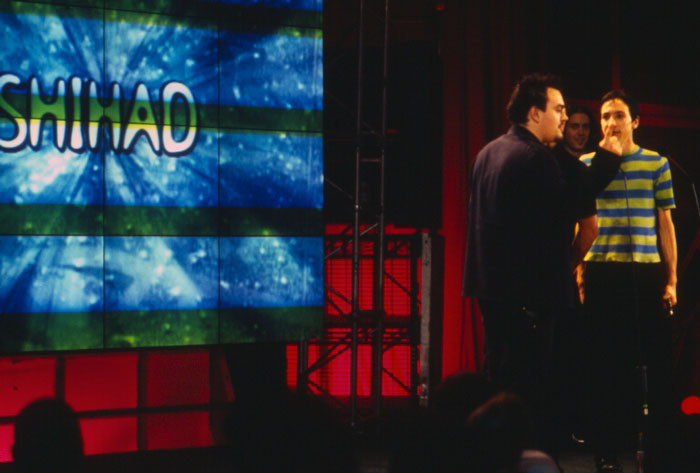

Shihad, 1998

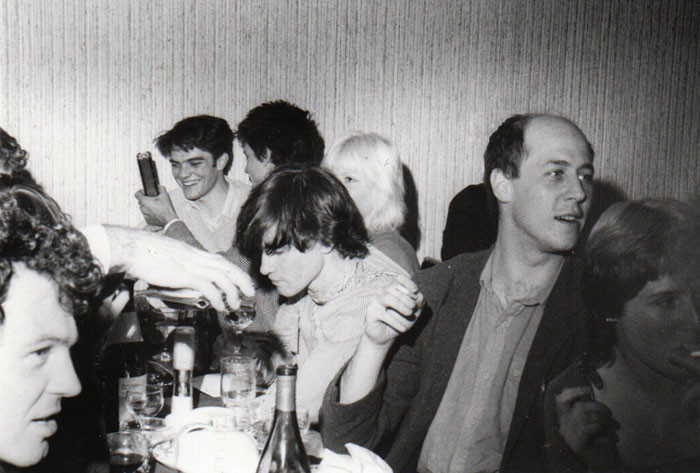

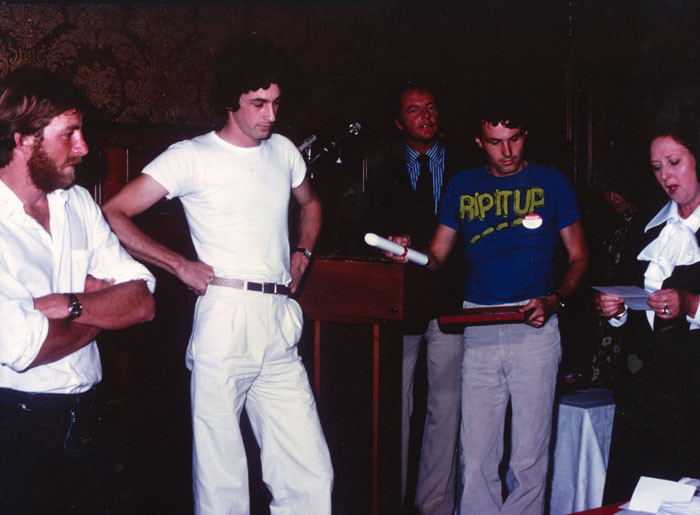

Don McGlashan, Paul Rose, The Newmatics' Sid Pasley, The Screaming Meemees' Tony Drumm, Sid's partner Angela, Simon Grigg and unknown, 1981

Helen Clark and NZ On Air's Brendan Smyth, 2002

With a renewed focus, RIANZ changed the name yet again to the now-familiar “New Zealand Music Awards”. The RATA “Pole” was retained as the trophy with the exception of 1978 when the awards were broadcast as a live Ready To Roll TV special and winners were presented with a gold-plated microphone and, in something of a jump back to the Loxene days, a framed gold disc.

The Dance Exponents, 1984

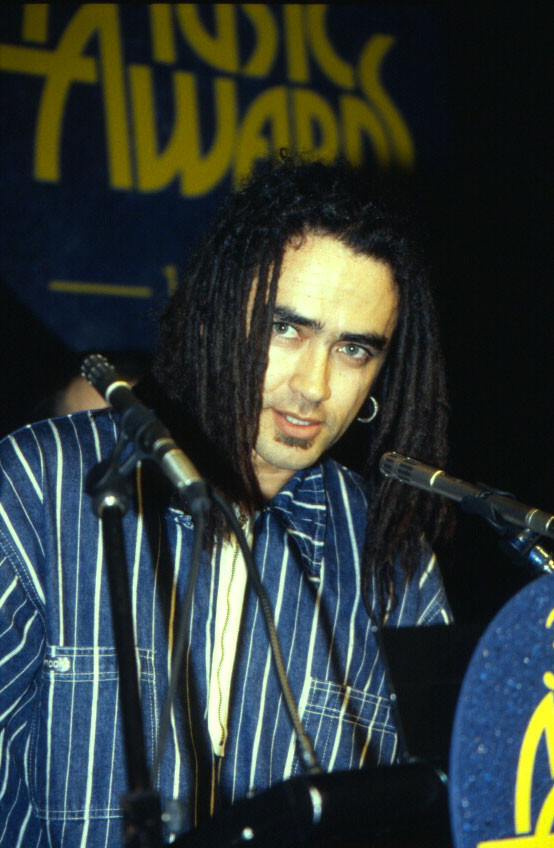

Supergroove with Charlie Tumahai (Herbs)

Smashproof, 2009

Julia Deans, 2001

Pauly Fuemana, 1996

FMR's Mark Ashbridge, Peter Urlich and Jonathan Hughes, 2000

Anita McNaught and Bill Ralston, 1996

Che Fu, 2002

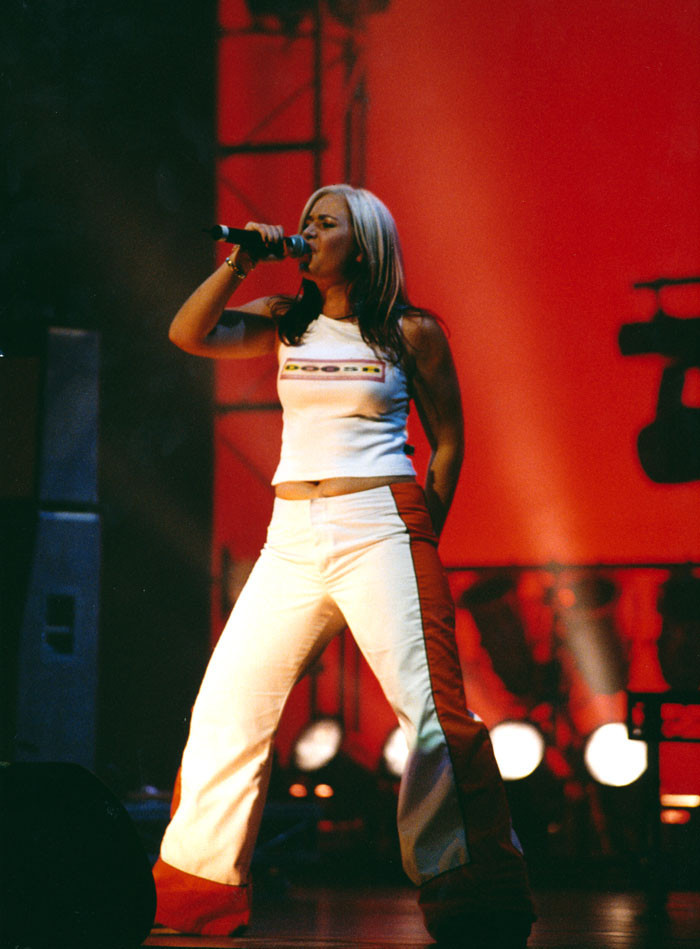

Emma Paki, 1995

Paul Ubana Jones, 1998

Dave Russell, Ray Columbus and Billy Kristian, the survivors of Ray Columbus & The Invaders, who won the first Loxene Golden Disc in 1965 for 'Till We Kissed'. They were being inducted into the Hall Of Fame, 2009.

Children’s presenter Stu Dennison, replete in brown dungarees, hosted the TV special, broadcast live from Avalon Studios in Wellington. The “made for TV” format meant that the show centred around live performances by nominees (John Rowles, Sharon O’Neill, Rodger Fox Big Band, Hello Sailor, Toni Williams, Golden Harvest) and trophy presentations were restricted to just two awards – one for Best Single (won by Golden Harvest for ‘I Need Your Love’) and the other for Best Album (won by Hello Sailor for Hello Sailor). The rest of the awards were presented at the old faithful White Heron in Parnell after the telecast had concluded. Simon Grigg recalls that there were no trophies for these awards, “just a rolled-up paper certificate”. Classy.

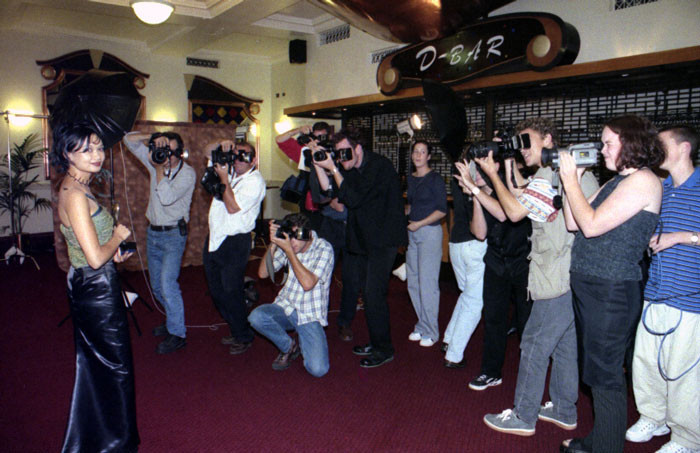

Bic Runga with the media, 1999

The Feelers, 1999

WEA Records' Tim Murdoch on the left, 1985

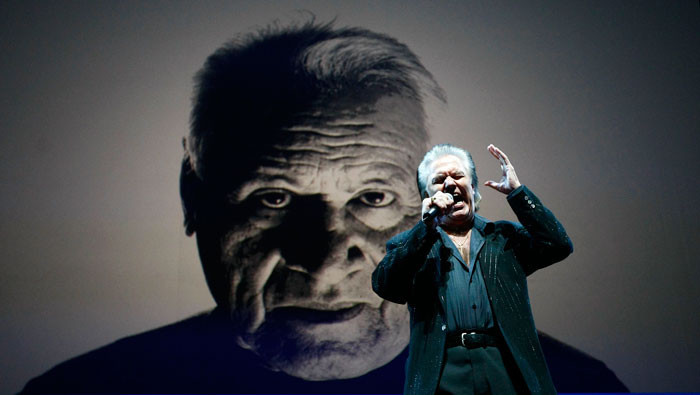

John Rowles performing a tribute to the late Sir Howard Morrison in 2009

Rodney Fisher with Goodshirt, 2002

After several years of low-key Auckland-based events held at the suburban Logan Park travellers hotel, the bar was raised when the awards were shifted to the Wellington’s Michael Fowler Centre for a black-tie affair that enabled RIANZ to wine and dine the capital’s politicians. The 1983 show also saw the awards return to prime time television, broadcast on TV One and hosted by Radio With Pictures’ Karyn Hay & Shazam’s Phillip Schofield. Prime Minister Robert Muldoon – who infamously described local music as “those horrible pop groups” – was clearly impressed enough to be coerced into presenting Most Popular Song. Perhaps his advisors assured him it would be a vote-winner; if so it didn’t work. Leader of the Opposition David Lange presented Top Artist and subsequently rolled the PM eight months later.

Malcolm Welsford, 1998

Mike Harvey in 1974

The Narcs in 1984

Chloe and Ray Columbus, 1996

Brevity might be soul of wit, but it was not the soul of awards shows. The 1983 show ran to over three hours and featured performances form DD Smash, Tim Finn, Pink Flamingos, Herbs, Coconut Rough, Topp Twins, The Body Electric, Monte Video & Shona Laing, Shane, Hogsnort Rupert and Peter Posa.

Co-host Karyn Hay returned for hosting duties in 1984, but was later censured over her off-the-cuff comments about the lack of local content on radio. As RipItUp assistant editor Russell Brown noted in his report of the 1985 awards, “Karyn Hay boycotted the [1985] ceremony after being warned that any out-of-line comments like those of last year would result in an unscheduled commercial break. But the Prime Minister [Lange] came on and said pretty much the same thing Karyn had said last year; that NZ radio must support and acknowledge NZ to a much greater extent.”

Bic Runga from afar, 1998

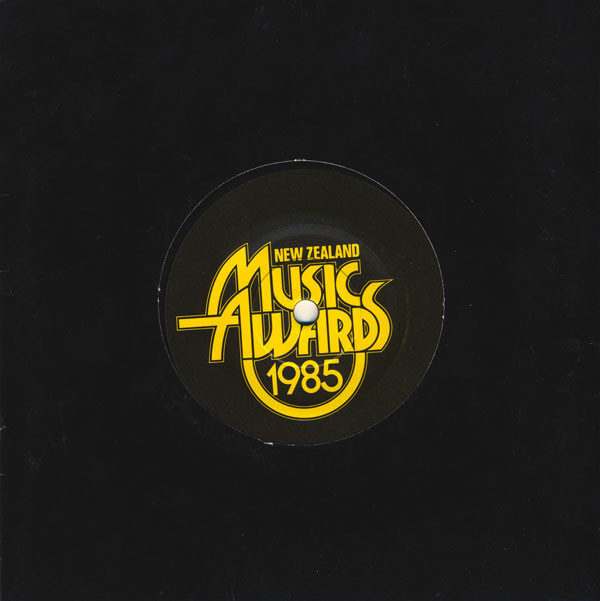

The 1985 invite was a one sided playable 45rpm single

Ladyhawke, 2009

Bruno Lawrence, 1984. Bruno was nominated as a finalist in the very first Loxene Golden Disc in 1965.

Colin Hogg, writing for the NZ Herald, had also commented that at the same year’s APRA Silver Scroll Award, “Minister of Broadcasting Jonathan Hunt, handed down an ultimatum that a local music quota would be imposed if programmers didn’t adopt a more parochial approach”.

Andrew Fagan, on the other hand, used the event to complain about new regulations requiring in-board motors for all sea-going yachts.

After three years in the capital, the show moved back to Auckland in 1986 and marked the retirement of the “Pole” trophy after 12 years’ service.

Michael Glading, Sony boss and Chairman of RIANZ, 1998

Anika Moa and Dan Sperber, 2002

The Finn Brothers, 1993

The Block era 1987-1992

What could a new trophy look like in the neon-soaked late-80s? Whatever the thinking was, it has to be said that “The Block” was entirely distinct and could no in way be confused with its predecessor. Made from a slab of solid steel and measuring 23cm high by 10cm wide by 5cm deep, it is most frequently likened to a VHS cassette. Aside from its dubious aesthetic merits, The Block also receives the award for being the heaviest trophy ever presented, weighing in at a whopping three kilograms (compare that to the mere 800 grams of the current trophy).

Flying Nun's Lesley Paris with one of the disintergrating perspex twirls, 1994

Grant Fell, 1995

Dave Dobbyn, 2001

1987 featured a curio as well, an award for Best Cast Album (won by Stewart MacPherson for Pirates of Penzance). The category had never appeared before and never would again. Amongst other categories to make fleeting visits onto the list are such things as Album of Educational, Cultural or Community Service Merit (1976), Best Film Soundtrack (1983-1989), Rising Star Award (1996 – an early precursor to today’s Critics’ Choice Prize), Radio Programmer Of The Year (1998-2003) and the succinctly monikered Outstanding Contribution To The Growth Of NZ Music On Radio (2005-2007). And while the awards are generally focused on recorded output, it didn’t stop a Best Songwriter gong being handed out from 1988 (Rikki Morris ‘Nobody Else’) through to 2005 (Dave Dobbyn ‘Welcome Home’).

Dinah Lee inducting Ray Columbus & The Invaders into the Hall Of Fame, 2009

DD Smash with their 1983 haul

The Mint Chicks, 2009

Dalvanius with a member of the Patea Māori Club, 1984

The Perspex Swirl era 1993-1994

Despite a vibrant music scene, 1993 saw a serious downsizing of the awards, and was held for the one and only time at The Powerstation (compared with the Aotea Centre the previous year) with a miniscule budget of around $40,000. After a shake-up in the organising committee, 1994 saw a return to the tried-and-tested hotel ballroom. This time the awards went to the Pan Pacific on Mayoral Drive (later renamed as the Carlton, which would also be a venue in later years), but both years will be best remembered for the decidedly hokey trophy – a stylised treble clef made from twisted green Perspex atop a wood-based plinth. These were notoriously fragile with very few making it out of the venue in one piece. By this time, TV coverage was limited to delayed coverage the following day. This and a general lack of marketability seems to have spurred RIANZ into action, and the 1995 awards saw a change of venue and another change of trophy.

The Mutton Birds, 1993

PNC, 2007

Helen Clark with Paul Rose, 2002

The Tui era (first generation) 1995-2005

In 1995 the RIANZ board agreed that a new trophy should be commissioned and “a requisite of the design … should be that it looks good on television” (Source: RIANZ board meeting minutes). TV production designer Nicola Marshall was tasked with the job and her design, the Tui trophy was ushered in – a stylised design representing New Zealand’s native songbird. This first generation Tui trophy was originally sculpted by Alex Kennedy and cast from solid bronze, weighing in at a hefty 1.9 kilograms. The centre area was filled-in and coloured a mottled green to replicate the look of paua shell.

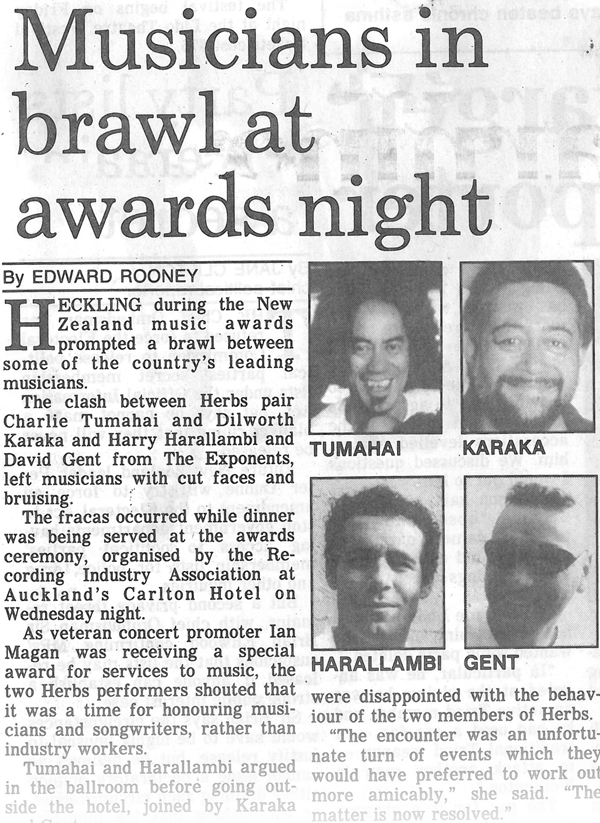

However, the show made the headlines for all the wrong reasons when a fight broke out between members of Herbs and The Exponents. “Mayhem at music bash” screamed the predictably histrionic Sunday News, going on to report on the verbal interjections made during the ceremony and the ensuing punch-up outside Auckland Central Police Station. Although Herbs ostensibly took umbrage at a lack of a Māori category, Neil Finn’s observation that “the food didn’t arrive until after everyone had drunk so much” more succinctly explained the cause of the debacle.

Trouble at the awards ...

The absence of a live televised show also garnered column inches, with fingers pointed at TVNZ’s apparent lack of commitment towards local music. The state broadcaster eventually conceded to showing a highlights package on the Sunday morning with costs covered by RIANZ. However, with the relationship between the parties strained, the following year's show moved to TV3.

For 1996 and 1997 the decision was taken to team up with the New Zealand Entertainment Operators Association (NEOA) in order to provide a broader, “variety” appeal for TV audiences and to share production costs which had jumped up dramatically to around the $400,000 mark. The resulting shows were heavy on the cultural cringe scale, with an insistence on guest international performers including Melissa Etheridge in 1996, Chris Issak in 1997. Fortunately this trend was scuppered when the awards returned to a wholly RIANZ-run affair in 1998 after a general feeling of unease that the co-brand concept distilled the promotion of NZ music. Other than the occasional international guest presenter, the NZ Music Awards remains resolutely focused on celebrating and promoting the local industry.

An embracing moment, 2002

Greg Johnson

Citizen Band with WEA's Tim Murdoch and Shona McFarlane, 1977

Then CEO of RIANZ, Chris Caddick, arriving at Vector for the 2011 music awards

However, this period was not without logistical hurdles. Harking back to the RATA days, dual-venue ceremonies returned (the main show and “blue chip” awards at one venue; the function and other presentations at a hotel ballroom).

Board member Adam Holt (Universal Music) recalls how abysmal these shows were, “The ‘minor’ awards were filmed with no audience while the industry guests were made to wait out the back of the St James – those that hadn’t dived off to the nearby London Bar.”

Sharon O'Neill, 1980

Simon Grigg, Roger Shepherd and Doug Hood, 1988

Holt says that the lack of professionalism, as well as a small budget, combined for an event that the artists weren’t proud of. Eligibility, administration and judging was also an issue; in one case Don McGlashan was both judge and nominee. Aghast that the situation had been allowed to occur, McGlashan excluded himself, but the die was already cast that the awards were little more than an industry back-slapping exercise.

Eventually the awards were moved to the Aotea Centre, a venue previously used in the mid-90s. Whilst the Aotea Centre made it easier to stage both show and function, accommodating TV rostrum cameras was a challenge and it was painfully obvious when the industry audience vacated their seats to head to the bar. So after four consecutive shows at the Aotea, change was in the air once again.

Helen Clark presnts Eldred Stebbing with a Lifetime Achievemnt Award, 2002

The Patea Māori Club with The Narcs, 1984

The Tui era (second generation) 2006 onward

Holt and fellow board member Chris Caddick (EMI Music) resolved to push for change, although they met with dogged resistance from the RIANZ board who were reluctant to expose the organisation to costs. Holt and Caddick argued that a bigger budget show would result in an event that was more attractive to sponsors. The gamble was to triple the budget of the show, which had slipped back towards the $100,000 mark, with the aim of making it self-sufficient within five years (the target was ultimately achieved in three years).

Eligibility rules were resolved and finally committed to documentation. Professional PR and event management companies – Pead PR and J&A Productions respectively, involved since the Aotea shows – raised the level of professionalism on all fronts, and continue to do so today.

In 2006, the next phase of awards history was ushered in, driven by the executive team of Managing Director Campbell Smith – a seasoned promoter, artist manager and entertainment lawyer – and Adam Holt, who was now Chairman of RIANZ. First the Tui got a makeover, being redesigned and manufactured from a considerably lighter, gold-plated aluminum. Although at a cost of $700 each, the Tui is no lightweight trophy. Responding to a call for more public engagement, the show was moved from the Aotea Centre to its current home at Vector Arena in 2008, which not only allowed for banquet seating but also meant that up to 6,000 members of the public could now experience the awards show.

Tadpole, 2000

Nigel Stone and Rocky Douché, 1993

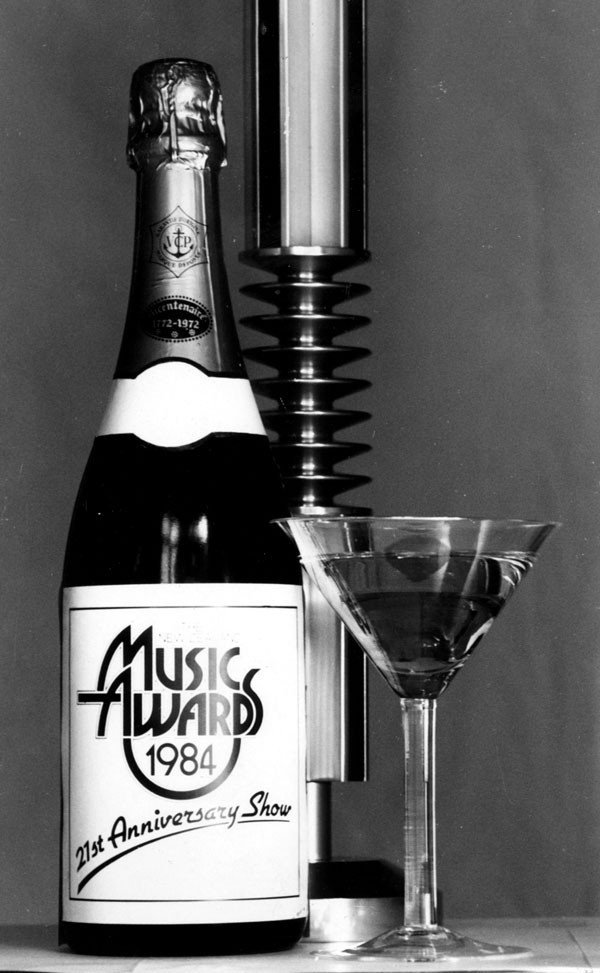

The 1984 invite cover

2007 saw the introduction of the Legacy Award (presented to rock and roll pioneer Johnny Devlin), which also doubled as an induction into the NZ Music Hall of Fame – an overdue idea that had been mooted by the RIANZ board since at least 2001. The Legacy Award brought the tally of awards presented during the main ceremony to 24. Six further awards are presented throughout the year (Jazz, Folk, Childrens, Producer, Engineer, Cover Art) with the ancillary Critics’ Choice Prize also awarded to an upcoming artist who shows promise of becoming a future Tui winner.

In 1965 the judging committee for the Golden Disc was a mere five people (three broadcasters, a journalist and a sponsor representative). Fourteen people – mostly journalists – comprised the panel in 1991. By 2000 there were 30 judges made up of TV, radio, press, retail and industry. This was seen as an improvement on the previous year’s tally of 20 judges. In 2003, Adam Holt optimistically suggested increasing the panel to 300 but the board resisted, only increasing to a meagre 50.

Jon Toogood, 2000

Karyn Hay, 1984

Annie Crummer, 1994

However, if the history of the awards can be seen as constant process of refinement, the modern awards certainly reflects an inclusiveness that would have flabbergasted previous organising committees. In 2015, 223 people make up the Voting Academy, which adjudicates on the general categories, and 12 Voting Schools made up of an average of 10 judges steer the specialist categories. The votes are cast online and independently audited to create the lists of finalists and ultimately, the winners.

Throughout its 50-year history, the music awards have evolved and adapted to meet change and expectation, as befits an award that celebrates the rollercoaster of popular music tastes. Somewhat late to the party, Best RnB / Hip Hop Album didn’t become a category until 2002 (winner: Che Fu The Navigator) then dropped out to return in 2004 as Best Urban / Hip Hop Album. Best Roots Music Album appeared in 2003 (winner: Trinity Roots True) before also dropping out for a year, returning as Best Aotearoa Roots Album before becoming Best Roots Album once more in 2011. 2003 also saw the introduction of Best Dance Album, which became Best Dance / Electronica Album the following year and then just Best Electronica Album in 2010, which was also the year Best Pop Album was inserted into proceedings.

The 1998 hosts: Ice TV's Jon Bridges, Petra Baghurst and Nathan Rarere

Pre-show ...

Scanning through the list of the 850 trophies that have been handed out in the last 50 years (as well as at least three times that number in nominated artists) shows a snapshot of the country’s music makers in any given year. Even by those numbers, it is still not a comprehensive list, and like any “Best Of” list, it will always provide a forum for heated debate. Yet regardless of fluctuating categories, venues, trophies and commercial pressures, the Music Awards have remained a constant celebration of New Zealand’s homegrown music for half a century. Here’s to the next 50.

The award programmes and trophies

--

Trivia

Banks, phones and soft drinks: National Bank, United Building Society, Clear, Vodafone, Pepsi, Coca-Cola & L&P have all been naming rights sponsors at various times.

Dave Dobbyn has received more trophies than anyone else – 14 solo, 13 with DD Smash and two with Th’ Dudes.

Bic Runga has the most trophies by an individual with 20. That number includes five technical awards, including two for Best Producer won by Bic herself.

Peking Man won a record eight trophies in a single year. This record has never been beaten, and remarkably took 18 years before being equalled by Scribe in 2004. The Naked & Famous (2011) and Lorde (2014) have also since equalled the record.

Links

Aotearoa Music Awards official site

Aotearoa Music Awards Facebook page