The music fanzine, that constant companion, confidant and often-stern ideologue of contemporary rock and roll movements, came to increased prominence during the mid to late-1970s British punk movement.

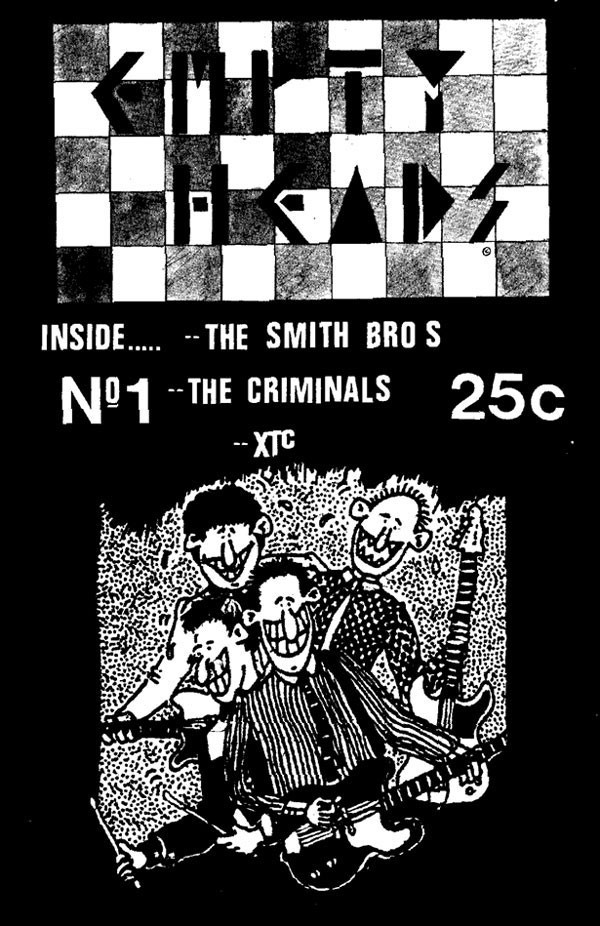

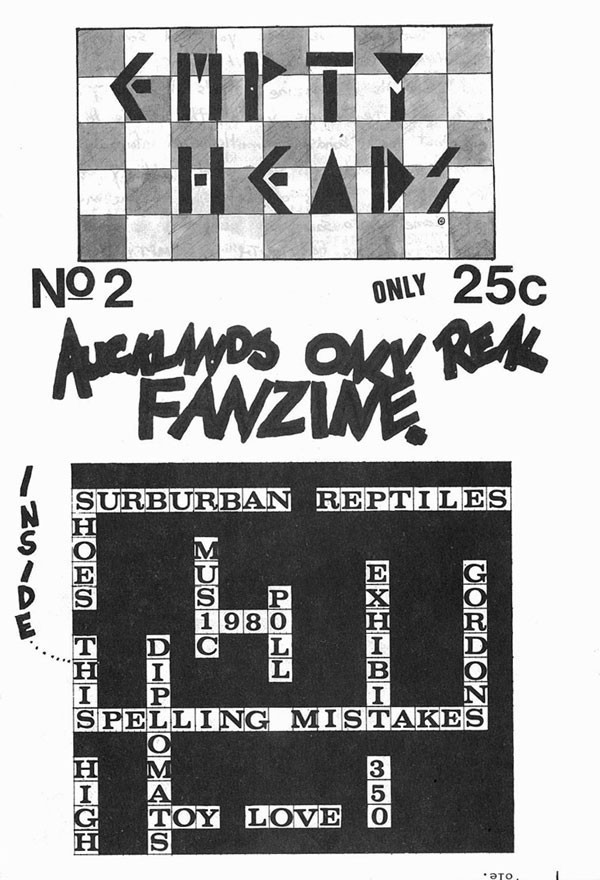

But this form of self-publishing didn’t appear in New Zealand until 1980 when the printed, low-budget Empty Heads and Push appeared in Auckland record shops.

Empty Heads was edited by Paul Luker, an apprentice photolithographer. Luker later played in Phantom Forth, a mid-1980s Flying Nun Records act and his own This Is Heaven, and he ran the well-packaged and sourced Industrial Tapes tape imprint. Empty Heads featured a tidy layout complete with clear reproduction of photos.

Post-punk orientated interviews with Shoes This High and The Pleasure Boys indicated some editorial promise (Luker trained for a year as a journalist) and its cover price and minimal ads showed an appreciation of commercial reality.

Empty Heads stalled at three issues despite increasing its print run to 1,000 copies and widening circulation out of Auckland’s inner city record shops to like-minded shops in other centres, and it slipped away largely unnoticed. The only historical record of the publication’s existence outside the actual fanzines is a small advertisement and review in music monthly, RipItUp.

In many ways Paul Luker and Empty Heads were typical of punk fanzines and their creators. Luker was a punk music fan influenced by the punk and post-punk scene in England, and he was an avid reader of UK music weekly NME. In time he became a musician and formed and headed an independent record label.

Fanzines themselves have a long history that can be traced back to The Comet, a science fiction fanzine first published in May 1930 by pioneer science fiction fan organisation, Science Correspondence Club.

Since then the subject matter and focus of fanzines has widened considerably. Politics, literature and poetry, religion, sports, films, television, ecology and erotica have all become the subject of fanzines.

As there are also commercial magazines covering those subjects, a distinction needs to be made. In Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, Stephen Duncombe defines fanzines as “non-commercial, non-professional, small-circulation magazines, which their creators produce, publish and distribute by themselves.”

Punk fanzines supported, defined, reflected and marketed their community’s musical and social activities and political beliefs. In the 1980s New Zealand’s punk community headed underground and became more rigidly defined both in dress style (the punk uniform of Doc Martens boots, bannered shirts or T-shirts, short and spiked hair, and variations on this), outlook (the outsider cult with a victim mentality and a distortion pedal) and sound (harder, more metallic and less melodic).

Its musical and stylistic rigidity was matched by an ideological rigidity. The punk rock community, through the influence of hippie anarchist punks such as Crass, Conflict and Flux of Pink Indians, the distant sounds of UK punk’s working class ideology, combined with New Zealand’s own fraught atmosphere of civil discontent caused by the violent Springbok rugby tour of 1981 and the non-violent anti-nuclear movement of the early to mid-1980s, had absorbed some of the modern left wing’s more confrontational political concerns.

The music-related lifestyles and politics of punks kept them outside of the mainstream of New Zealand society and the fast changing nature of popular music trends kept them out of the commercial music media, which displayed an almost total indifference to punk rock after the early 1980s. This fuelled a need for information and identification which fanzines quickly filled.

The punk and post-punk era’s enabling do-it-yourself ethic was also complementary to the production of fanzines. Fanzine publishers were able to use new technology through increasingly available photocopy machines to print their magazines (cue much furtive illicit photocopying by would-be punk publishers).

Photocopying was cheap in contrast to commercial printing and the machines were simple to operate and able to copy, resize and reproduce graphics as well as text. They were also imbued with credibility by the UK punk fanzine splurge of the mid to late 1970s.

This combination of a small, marginalised sub-culture and new technology begat a fresh surge of spiky opinionated punk fanzines in New Zealand in the mid-1980s under such names as Anti-System, Anarchy, Outrage and Serious Intent, Communicade, Ha Ha Ha, PMT, ANI, Divided We Fall, Submission, Positive Approach and Spit On Trend.

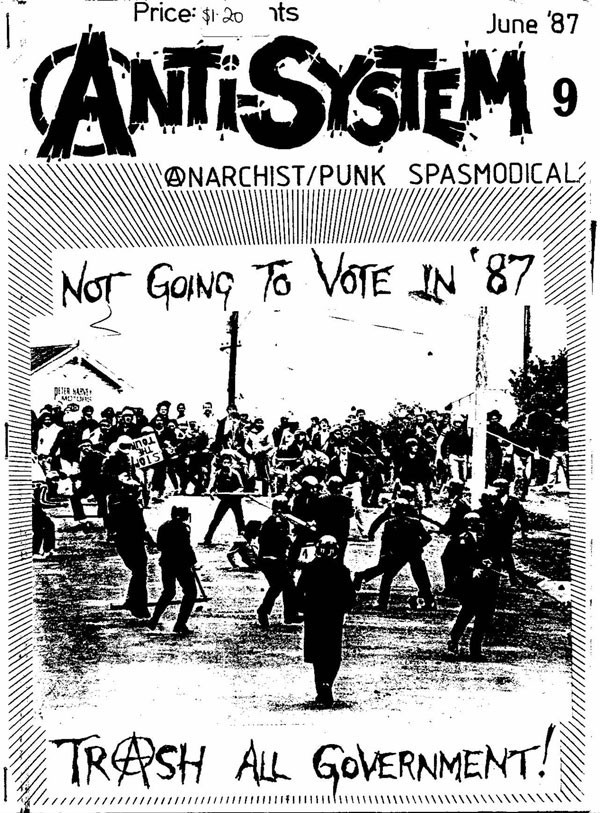

The longest lived was the Wellington “spasmodical”, Anti-System, which managed 13 issues between November 1985 and October 1990, when it became Social Disease, which in turn survived to issue 16 in February 1991. There was a revival issue in March 1997.

Anti-System’s contents were a typical 1980s punk fanzine stew of politics, cartoons, punk tape reviews and interviews with groups active in the Wellington punk and alternative scene. Issue one featured interviews with Wellington punk acts Number Nine, Wazzo Ghoti and Flesh D-Vice.

Published in an A4 photocopied format by Simon Cottle from Kilbirnie, Wellington, Anti-System and Social Disease showed a great deal of journalistic promise. Stories usually come from primary sources and were reproduced with very few spelling mistakes or errors, a constant in most fanzines examined here.

All the issues had a nominal cover price to allay costs, included some ads, and in later issues, practical matters like an index were included. The layout also got tidier and poetry started to appear amongst the vegetarian recipes, stories on Northern Ireland, Anarco-syndicalism and punk acts such as New Plymouth’s Casualty.

Anti-System’s seventh issue demonstrates both the advantages and downside of fanzine style primal reporting. Dated 18 November 1986, this issue is dedicated to Neil Ian Roberts, the 22-year-old Auckland anarchist punk who attempted to blow up the Wanganui Computer Centre, the central depository of police and Government intelligence on 18 November 1982. Roberts died during the action.

It was an ideal opportunity to examine this rare and under-reported outbreak of New Zealand political terrorism from a different perspective.

Despite a scorning of conservative press coverage of punk rock, Anti-System features a montage of clippings from the mainstream media that identifies “Neil Ian Roberts (as) 22, single and unemployed, from an anti-establishment background,” stating “he long held anti-social attitudes and was inclined to protests of various kinds” and that he’d been identified by his fingerprints, “which were on police records”.

The newspapers noted Roberts’ family background and that he was an avid war gamer, attaching him to then current urban myths.

Most reports said Roberts cased out the centre the previous week before commuting from a friend’s house near New Plymouth to explode the bomb. A message spray painted by Roberts on a toilet wall opposite the Wanganui Computer centre read, “we have maintained a silence closely resembling stupidity” with an anarchy sign and the words – “Anarchy Peace Thinking”.

The closest the mainstream press got to sensationalism was the astute journalist who tracked down the tattooist who etched “This punk won’t see 23” on Roberts’ chest.

In a promising beginning to their commentary, Anti-System described Roberts as “a well known figure, who frequented Auckland inner city streets, pubs and band venues” and quoted the anarchist Emma Goldman (from 1901) in what could be the most revealing insight into the emotional terrain the otherwise peaceful Roberts inhabited:

“Men of his type are in reality super sensitive beings unable to bear up under too much social stress. They are drawn to some violent expression even at the sacrifice of their own lives because they cannot quietly witness the suffering of their fellows.”

The mainstream media had also missed the relevance of the scene Roberts emerged from. A sometime drummer with Mount Albert punks The Executioners, Roberts was from a punk community, at odds almost weekly with the Auckland Team Policing Units who had taken a hard-line attitude towards the Queen City’s punks, suggesting that Roberts’ anarchism was as much based in experience as idealism.

Another feature of fanzines is tucked away at the back of Anti-System: an extensive list of New Zealand fanzines with contact addresses and some information on them. Fanzines would extend this form of networking to bands and record labels and overseas fanzines. The regionally based punk community proved highly effective at networking a nationwide punk community via the dissemination of ideological information, sub-cultural reportage and punk rock news.

Anti-System was one of an abundance of Wellington punk fanzines reflecting an active punk community in New Zealand’s capital. Communicade, produced by Compos Mentis, a punk act from Upper Hutt, appeared in 1985 sporting a cartoon picture of a punk rock Peanuts on the otherwise bland cover. Coverage included overseas bands and Five Year Mission, a Napier punk group, reflecting the local and international nature of the punk movement. Regional scenes were a strong feature of New Zealand punk throughout the 1980s. New Plymouth, Gisborne, Hamilton, Levin, Christchurch, Dunedin, Wellington, Invercargill and even small towns such as Morrinsville had punk acts. Fanzines often followed.

Issue two featured a letter from Positive Approach fanzine from Mount Wellington, Auckland, which was published by punk group Service 42. Fanzines were such a part of the punk scene that they warranted coverage in themselves.

Also included is an editorial lamenting the appearance of young Wellington punks wearing Nazi regalia and a list of an individual’s rights when confronted by police that reflected issues faced by the punk community.

By the third and final issue of Communicade the writing and layout had improved (but not the covers) and the menu included an interview with Casualty (from New Plymouth), a New Zealand punk scene update, more overseas punk news, and punk capitalism in the form of bootleg tape ads.

Out of south Wellington in October and November 1986 came Divided We Fall, a folded A4 fanzine with a heavy paper cover in primary colours, put together by Craig and Michelle (no surnames given). The cover art is mediocre and the editorial content average.

Of interest in Issue One is a letter from Ratfink, a Wellington punk disgusted at the violence between skins and punks in Christchurch that exposed the fractious nature of the punk community.

Elsewhere, South African apartheid is examined. The linking up to overseas punk communities also resulted in an interview with Moscow, a Polish punk group, and a British scene report.

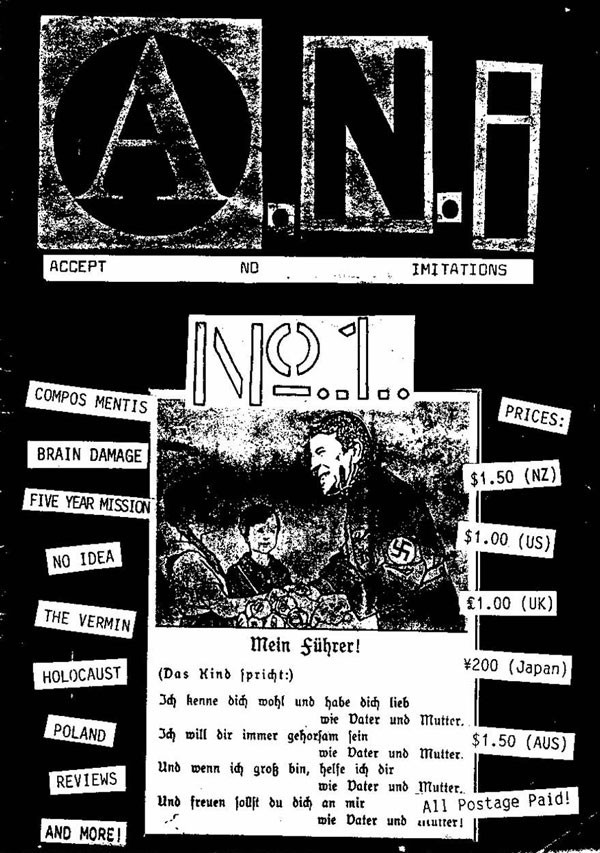

Closer to home, there’s an interview with Auckland anti-drug punks Defiance – Blair Welch, Rupert Ross, Paul Ohlsen and Adam Decay (Williams) – who published ANI (Accept No Imitations) – an NZ punk-heavy fanzine that lasted for two issues and featured stories on Five Year Mission, Brain Damage, Compos Mentis, No Idea (from Levin), Vermin, Holocaust, Service 42 and Corrective Training (ex-Tin Foil Murders from Napier). Adam Decay (Williams) was a proficient cartoonist and his work features heavily.

Issue three of Divided We Fall from March 1987 showed a welcome sense of humour in a cartoon about the beginnings of Dunedin punks The Mindfuckers – a counterpoint to the usual heavy-weights-on-young-shoulders fanzine interviews.

Three more issues of Divided We Fall appeared, featuring New Zealand punk acts such as Invercargill’s Moral Fibre, Casualty from New Plymouth and Last Orders from Auckland, and demonstrating once again the national networking of regionally based punk communities.

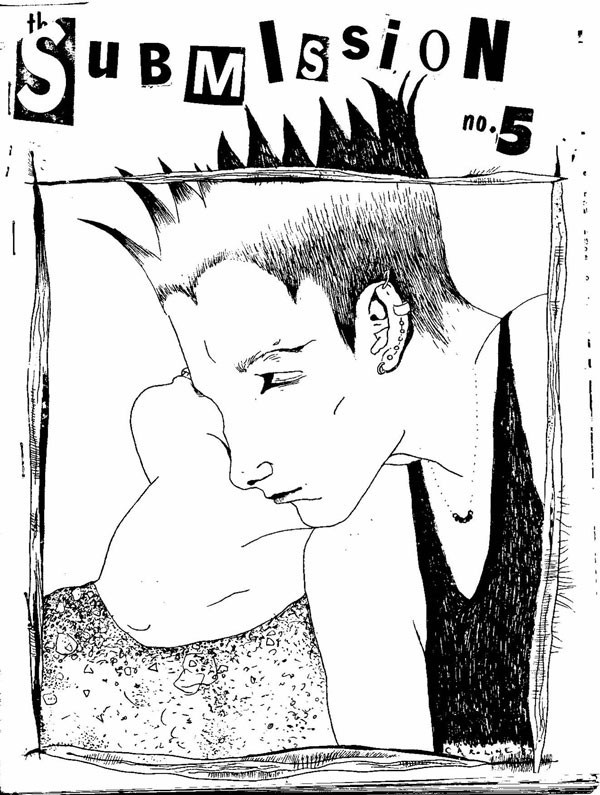

In November 1986 in the Wellington inner city suburb of Te Aro, Ania Glowacz began writing and printing the A4 sized Submission, a punk fanzine with feminist concerns and a taste for hard punk rock, including Wellington’s Flesh D-Vice.

All the covers are eye-catching, from the Queen picking her nose through to mohawked punks and Mark E. Smith from Manchester post-punk group The Fall. In the fifth and final issue in late 1987 there are some revealing shots of Wellington punks Number Nine on tour and New Plymouth’s Sticky Filth faceless on their doorstep as photographed by their local daily newspaper after winning the 1987 Taranaki Battle of The Bands.

Editor Glowacz would go on to write in Real Groove, NZ Musician and RipItUp as an enthusiastic reviewer of dark rock, following the path some fanzine writers would take to mainstream music media.

Burning rubber at the heavy metal end of punk’s highway was I Don’t Conform (six issues) published in Wellington in 1987 by Skuller and Balrog and featuring interviews with the by-now usual suspects Service 42, Vermin and Holocaust from Christchurch.

Second Dark Age covered similar ground as punk rock continued to fracture into musical sub-cults throughout the 1980s, having already seen hardcore, oi, anarcho-punk and positive punk pass its way.

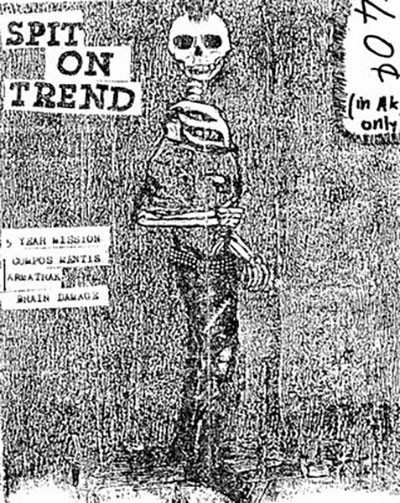

The Subvert Distribution Service was operated from Whangarei by Bryce and Brendon (no surnames given), the minds behind the hard punk fanzine, Spit On Trend (previously the Subvert Herald), and was one of several attempts to set up a central distributor of New Zealand fanzines.

The service didn’t last long and neither did Spit On Trend, despite being a neatly folded A4 fanzine with balanced layout, an excellent cover and the A-list of New Zealand punk groups. Five Year Mission, Compos Mentis, Brain Damage and Auckland’s Armatrak are interviewed within.

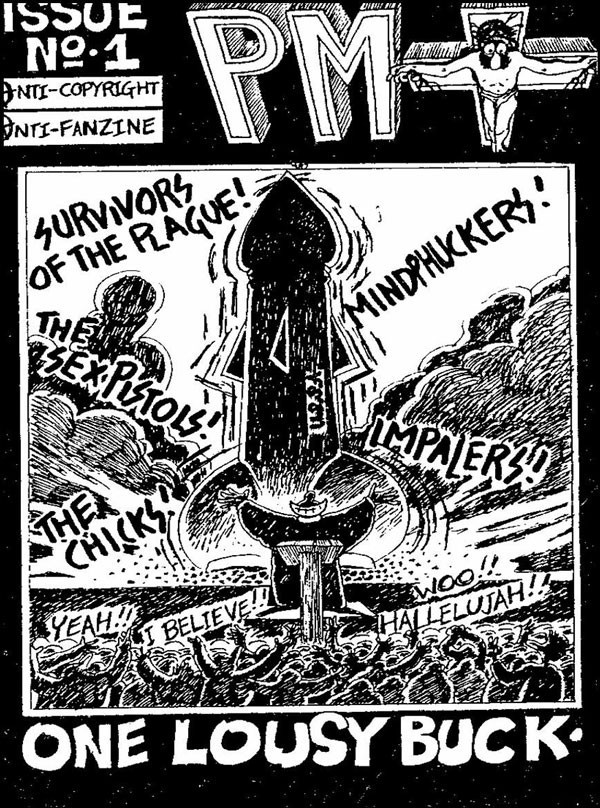

One of the best-realised mid-1980s fanzines was PMT, edited in 1986 and 1987 by John L and Tracey (no surname given) in Dunedin. Right from the eye-catching black and white cartoon cover, it’s a class act featuring Ourbert and Sam the Druggie Spaceman cartoons from Tony Renouf (former bass player of S.H.I.T. in Hamilton).

Coverage is confined to the Dunedin punk scene, giving a good idea of the extent of activity of there. Interviews include Dunedin punks ex-Government Life, The Unseen, The Impalers, The Ex-Pistols and The Chicks. Its promise soon dimmed and while the cartoons continued to be sharp and funny, local scene coverage gave way to overseas punk acts as the Dunedin punk scene faded.

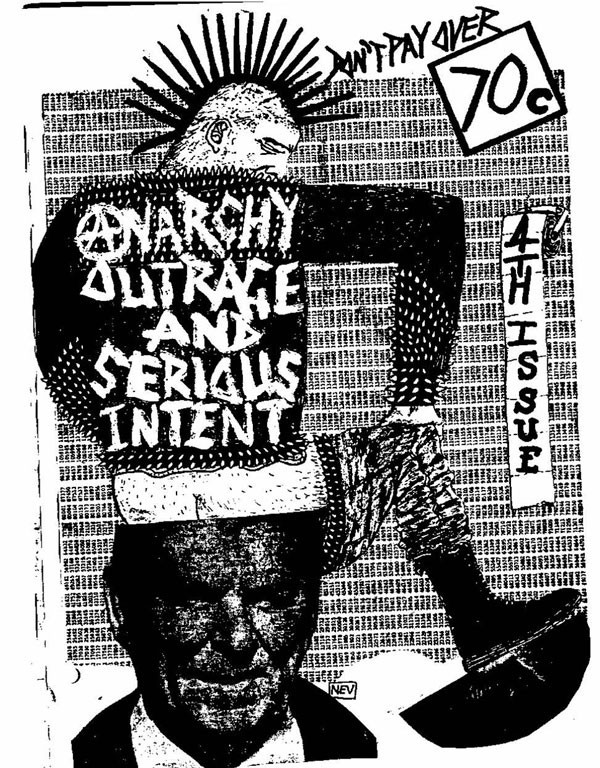

Auckland was the major source of punk fanzines outside of Wellington. Anarchy, Outrage and Serious Intent, a folded A4 photocopied fanzine by Armatrak's Stephen Moore and Simon Bendall lasted five issues from 1983 on. The fifth issue was titled as simply Outrage.

Its value lies in early wide coverage of the New Zealand punk scene, which quickly extends from Auckland in the first issue to include Wellington, Dunedin, Hamilton and overseas scenes (Finland).

Issue two features a review of the closing show at Auckland underage venue, SPAM, and the best of local off-centre rock and roll. Brain Damage’s Gonk from Greymouth interviews Christchurch punks ECF and sheds some light on the early 1980s Christchurch punk scene.

Issue three has scene coverage from Auckland, Hamilton and Wellington (Aftershock interview). The Hamilton piece is a coherently written report on the city’s tiny punk scene, which noted harassment of punks at local drinking establishments and the appearance of anarchist punks The Irritants and Melville punks S.H.I.T. as well as a new Hamilton fanzine, Ha Ha Ha.

The quality of Auckland’s punk fanzines was variable. The primary school level Dick Scratching Penis Breath seemed to exist principally to name-check the mates of the publishers. From April 1985, Blind Attack had few redeeming features other than a great cover and review of the demolition nights closing down Mainstreet cabaret, a report on the August 1983 anti-ANZUS No Nukes march in Auckland and a nifty Mutation Press – Parnell moniker. A little better was Equality Through Autonomy, a faded A4 photocopy fanzine published by Simon Coffey and K4.

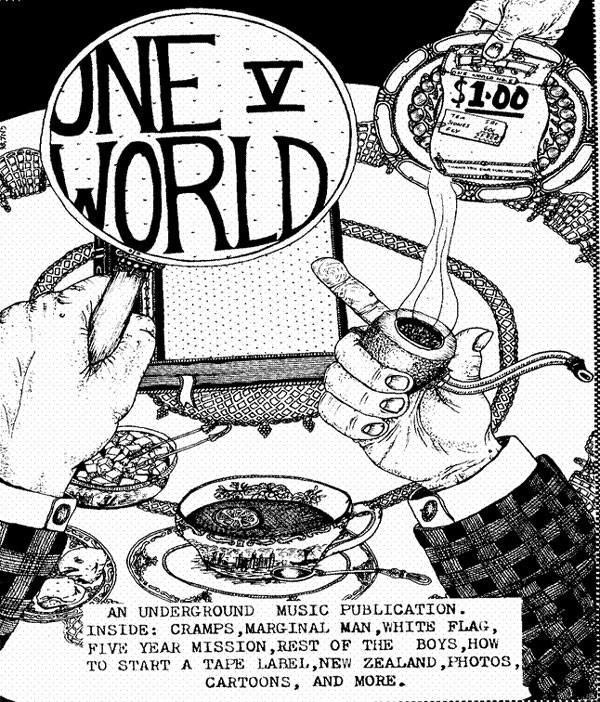

Neil Cartwright’s One World, a glossy printed colour fanzine, appeared in 1984, yet despite being a product of the early 1980s Auckland punk scene, it largely ignored it.

One World more closely resembled a low rent hippie magazine from the 1960s. Poor covers didn’t help, nor did a layout devoid of the raw charms and strange symmetry of most punk fanzines. One World lasted five issues from 1984 to 1985; each better presented than the last. It was eventually made available in South Africa, the United States and the United Kingdom.

Flesh D-Vice, Five Year Mission and Compos Mentis all feature in One World as does an article on how to form a tape label, although the most comprehensive and insightful interview is with US group The Cramps, as caught by Kerry Buchanan (ex Rooter and Terrorways drummer and RipItUp writer) on their first Auckland visit in 1986.

The value and potential utility of New Zealand punk fanzines from the 1980s in researching social and cultural history in New Zealand is their insight into a marginalised community. They show a community reflecting and debating its politics; its cultural mores; its varied participants; its international punk community connections; and its ethos.

Punk fanzines provided easy, cheap and immediate access to publication for writers, graphic artists, photographers and cartoonists. The language used and images and subjects selected tell a story of their time. For the best view of New Zealand’s largely underground punk culture of the 1980s you needn’t look much further than these street media. They did their job.