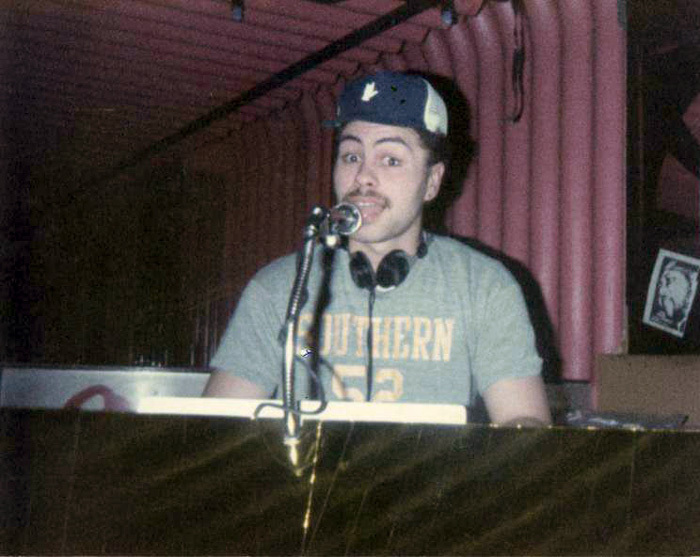

In the 1980s, a young Māori DJ who worked under the alias “Tee Pee” was the shining star of Wellington’s nightclub scene. An open-format selector with an early passion for hip hop, Tee Pee would mix, scratch and rap his way through nightclub sets and mix shows on student radio station Radio Active 88.6 FM (then 89 FM). By the time he left the capital in 1989 to move to America, he had shown off his skills on commercials and television shows and trained the next generation of Wellington DJs.

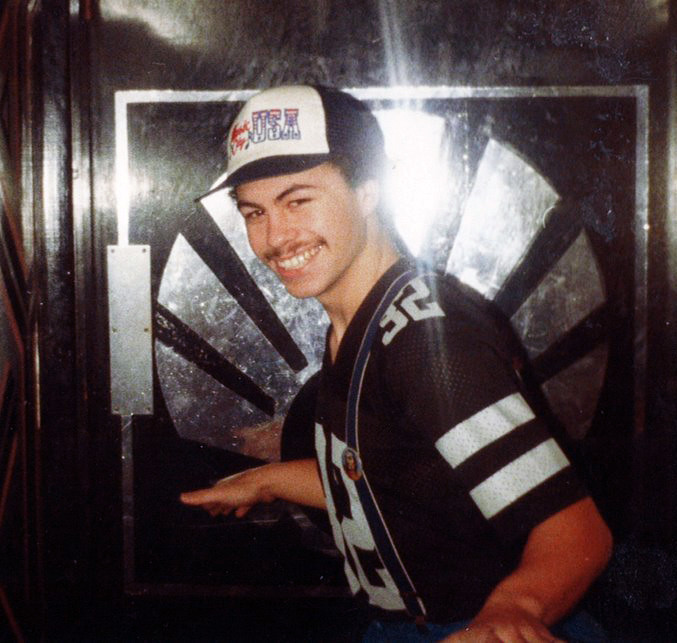

DJ Tee Pee, 1982.

Tony Pene, aka DJ Tee Pee, was born in Upper Hutt, and grew up in Newtown, Porirua and Wilton. When he was 14, Tee Pee started sneaking out to go nightclubbing at central city discotheques such as Uncle Albert’s Attic on Herbert Street (now part of Victoria Street). He was friends with a bunch of guys who loved dancing.

“We called ourselves The Funkateers,” Tee Pee says. “We went out and bought matching Italian boots with two-inch heels, and we had these brown jackets with a tag on them that said Funkateers. We were like that crew in that Roll Bounce film.”

Tee Pee and The Funkateers would hit the local discos and smash the dancing contests. Their best dancer was Steven Daniells-Silva.

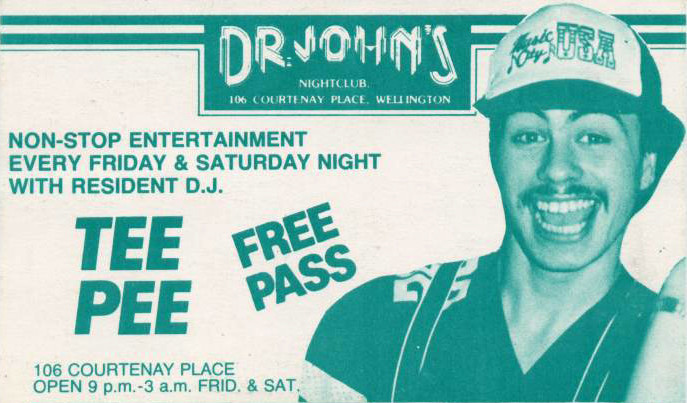

Steven’s older brother Mark Daniells (aka Moondog Mark), worked as a DJ at Uncle Albert’s Attic, Spats, and later on, Dr John’s on Courtenay Place. Dr John’s was a late-night club established by the Wellington nightlife impresario Ray Johns. Uncle Albert’s Attic was where Tee Pee heard hip hop for the first time. The first two songs that stood out to him were ‘Rapp Dirty/Blowfly’s Rapp’ by the Florida funk legend Blowfly and ‘Rappers Delight’ by the unforgettable Sugarhill Gang.

“I was like, what is this?” he recalls. “It was rhythmic, syncopated lyrics over a funky beat. Up until then, there wasn’t that fusion. There had been things that had influenced me, like ‘Flashlight’ by Parliament with that heavy synth, but it wasn’t until one of those early hip hop tracks that the switch went on.”

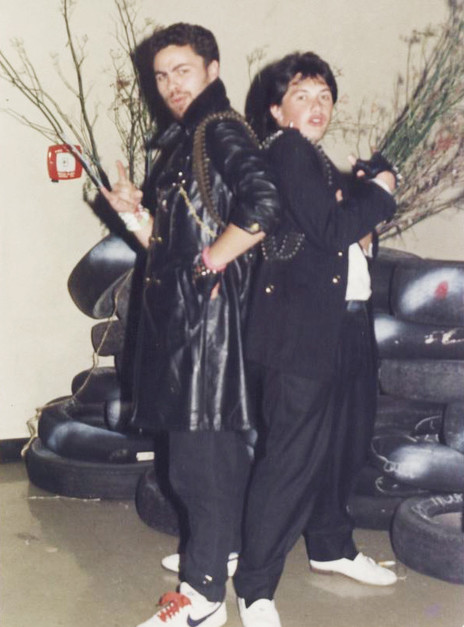

Tony "Tee Pee" Pene, regarded by many as the godfather of the Wellington DJ scene - Rhys B collection

In the late 70s, Moondog Mark was a huge figure in Wellington nightlife. His father, Pasi Tunupopo (Pasi Daniells, as he was known to the public) spent the early 1960s working as a drag dancer in Sydney, before returning to Wellington with his young family. On arrival, he opened The Purple Onion on Vivian Street, Wellington’s first drag club. The children grew up around nightlife, and Mark quickly became a formidable entertainer. He was a showman who would breathe fire and wear roller skates while DJing.

“Mark was a huge influence on me,” Tee Pee remembers. “I took my stage skills from him, and when hip hop arrived, I saw rapping, scratching and beatboxing as ways to enhance my show.”

In 1980, Tee Pee dropped out of high school to DJ at Dr John’s and work at Chelsea Records on Manners Mall (now Manners Street). Ray Johns had sold Dr John’s to his friend Billy Martin, who ran it as an all-ages nightclub. Nick Mills, who went on to – among many other things – own the Exchequer Saints (now Wellington Saints) basketball team and run the iconic Exchequer nightclub on Plimmer Steps, credits Billy with being one of the first people to really recognise Tee Pee’s brilliance.

“Tee Pee was this young sensation DJ,” he says. “He was a young kid who was real good, and Billy really discovered him.”

With Tee Pee behind the turntables, Dr John’s quickly became a mecca for young Polynesian youth. Although he’d play disco, new wave, electro and art-rock records by Blondie, XTC, Kraftwerk and Alan Parsons Project, hip hop was his passion.

In a mid-80s roundup of Wellington nightclubs, journalist Ruth Laugesen described Dr John’s as “Wellington’s hidden treasure”: “And the DJ! On his best nights he’s inspirational, charmful, he could save your life. His name is Tee Pee and he specialises in anything funky and wonderful that moves the feet, a mix of one-part disco classics (Jacksons, Parliament, Chic, Rose Royce, Anita Ward), one-part modern black sounds (Madonna, 52nd Street, the Gap Band, Whodini, the Sugarhill Gang) and one-part chart music (Wham, Prince, New Edition, New Order, Freeze).

“On his best nights he’s inspirational, charmful, he could save your life” – Ruth Laugesen

“He raps fast enough and strong enough to raise Atlantis from the bottom of the sea, or at lease to raise your feet from the bottom of your legs. And scratching? Easy. He colours in New Order’s grand design with pieces from other songs and suddenly ‘Blue Monday’ moves faster. You’ll like it here if you’ve been itching for a new dance stance, some relief from post-Human League swing-sway. At Dr John’s it’s more spin-click and a hippity-hop, a chance to dance your way out of your constrictions.”

Between working at Chelsea Records and DJing at Dr John’s, the record label reps took a close interest in Tee Pee, which meant he had access to promo records. “I thought that a DJ was only as good as their record collection, and I had the best record collection,” he reflects.

In 1982, New Zealand started allowing American basketball players to play for local clubs in the National Basketball League. In Wellington, one of the imports hired by Nick Mills’s Exchequer Saints was Kenny McFadden. Kenny was a huge influence on the first generation of hip hop heads in the capital. He grew up in Lansing, Michigan, with future NBA legend Magic Johnson before playing basketball for Washington State University. After suffering an injury during a game, Kenny was informed that his chances of getting drafted for the NBA were slim. However, his coach suggested he could play professionally for a team in Czechoslovakia or New Zealand. Two days later, Kenny was on a flight down under.

DJ Tee Pee on a Dr John's night club door pass.

For Kenny, arriving in Wellington was a culture shock. He was one of the only Black Americans in the city. The food wasn’t right, the nightclubs played rock music, and when he tried to watch late-night television, he’d be greeted by the TVNZ Goodnight Kiwi signoff cartoon. “He couldn’t believe that the Kiwi bird was singing him off at 10 pm,” Tee Pee laughs.

One afternoon, Tee Pee and Kenny randomly got talking on the street, and Tee Pee invited him up to Dr John’s. Kenny was thrilled to see breakdancing and hear a DJ playing hip hop and R&B when he visited. “I went and checked out Tee Pee,” Kenny remembers, “and he was playing some good music, so I started to spend a lot of time up there.”

For Tee Pee, being friends with Kenny came with a couple of bonuses. Kenny had a brother who worked as a DJ in New York. He’d record the best hip hop radio shows to cassette and mail them to Kenny, who would make copies for Tee Pee. Tape by tape, Tee Pee started getting his head around hip hop DJing. Kenny also liked to rap and started giving Tony pointers. Soon enough, Tee Pee was rapping, beatmatching and scratching during his DJ sets.

“It was a huge culture change happening here in Wellington at the same time it was happening in New York City,” Kenny recalls. “I was only two weeks behind what was going on in New York. We were ahead of the curve on most cities in the United States because hip hop started on the East Coast before it got out to the west coast. I think we were ahead of the West Coast, down under the Downunder.”

In 1983, Mark Cubey – editor of student paper Salient – came up to Dr John’s looking for a sponsor for The Uncut Funk Show, a weekly radio show he was launching the following week on Radio Active. Billy Martin agreed, but with one proviso. He wanted Tee Pee to feature on the show. Tee Pee nicknamed Mark “Mighty Mic C” and came up to guest a few times. When he wasn’t mixing hip hop, scratching or rapping on air, Tee Pee would sometimes play some of the cassette tapes Kenny was giving him.

DJ Tee Pee with boombox, c. 1984. The price is equivalent to $2250 in 2021 dollars.

“I would just say, this is DJ Tee Pee, I’ve got a new tape from the US, you’re going to hear US DJs and commercials,” Tee Pee says. “It was probably highly illegal, but, you know, it was Radio Active, man.” Quickly, Wellington’s first generation of hip hop fans started taping Tee Pee’s radio shows. In doing so, they made second-generation bootleg recordings of the American tapes Kenny had given Tee Pee. “I’d be down on Oriental Bay and I’d hear people playing the tapes I’d played on the radio,” he laughs.

By 1984, interest in breakdancing was exploding in New Zealand. In Wellington, young breakdancers – inspired by American films such as Flashdance, Wild Style and Beat Street, and the music video for ‘Poi E’ by Dalvanius Prime’s Pātea Māori Club – would gather outside Chelsea Records on Manners Mall. Tee Pee and Kenny made a point of hanging out while the young b-boys battled each other. Sometimes they’d bring down speakers and a microphone and rap.

Doing the dolphin, Manners Mall, Wellington, 1984. - John Nicholson. Dominion Post collection, EP/1984/0163/31-F, Alexander Turnbull Library.

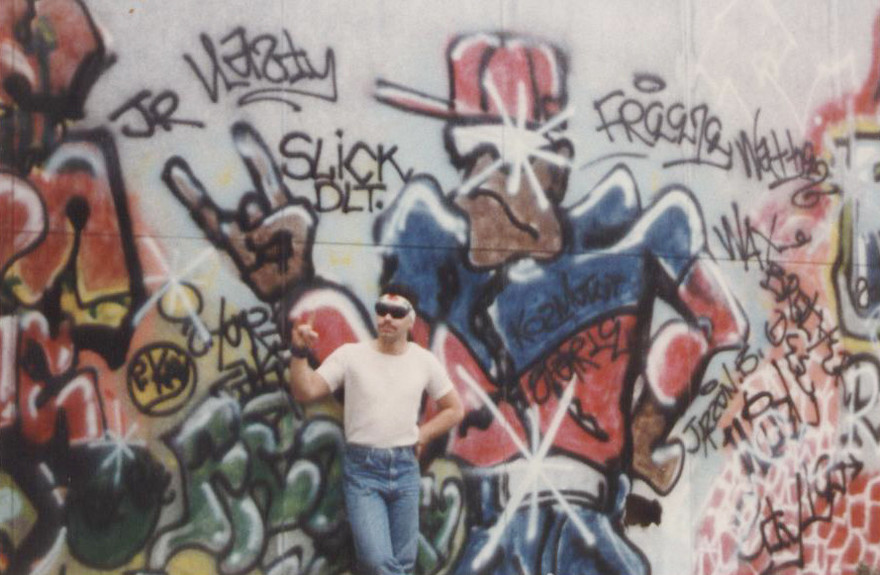

When the dance battles finished for the day, Tee Pee would hand out free passes to Dr John’s and encourage the breakers to come up to the nightclub. Some of those early b-boys included Upper Hutt Posse’s Dean Hapeta aka D-Word and Darryl Thompson aka DLT, and Kosmo Faalogo aka K.O.S 163 from The Footsouljahs. For that generation, seeing Tee Pee play at Dr John’s was an introduction to live rap. In the Aotearoa Hip Hop: The Music, The People, The History podcast, DLT describes the experience of seeing Tee Pee entertain the audience as “heavenly”, making it clear how influential he was. From there, it was inevitable that DLT and his peers would end up rocking stages as rappers and DJs.

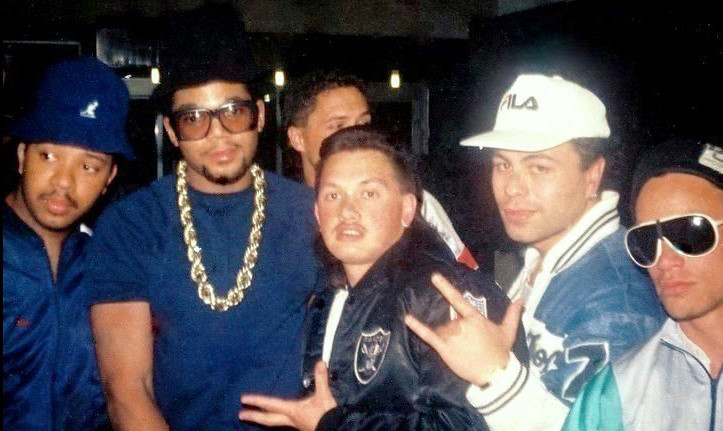

Run and DMC in Auckland, late 1988, with DLT (obscured), Rhys B (centre), DJ Tee Pee (in white cap) and D-Word from Upper Hutt Posse (far left).

At Dr John’s, Tee Pee began the process of training the next wave of Wellington DJs. One of his first students was Rhys Bell aka Rhys B. Rhys started as the toilet DJ: playing records while Tee Pee was using the bathroom. Under Tee Pee’s tutelage, he became a certified club legend in the capital and went on to represent New Zealand at the 1990 DMC World DJ Championships in London. Later, Tee Pee mentored the turntablist legend DJ Raw, who represented New Zealand multiple times at the DMC and ITF World Finals in the 1990s and early 2000s. In an extension of this role, he served as a judge at some of Wellington’s first rap and DJ competitions in the late 80s.

The decade rolled on and Kenny started bringing more and more basketball players to Dr John’s for their music fix. By this stage, Nick Mills was running Exchequer, the nightclub that sponsored his Exchequer Saints basketball team. Nick didn’t like the basketball players heading to another nightclub, so they decided to bring Tee Pee up to Exchequer. By 1985, he was DJing there regularly. Whenever basketball teams visited the capital, they would party at Exchequer after their games. As interest in basketball rose in New Zealand, so did Tee Pee’s fame.

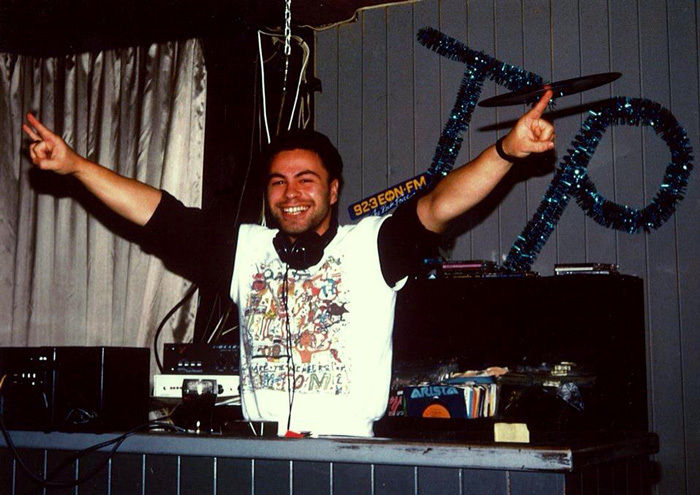

DJ Tee Pee and Rhys B.

That year, Wellington Motorcycles asked him to record a rapped radio advertisement for them, which led to him rapping on televised adverts for milk bottles and a Kentucky Fried Chicken belt-bag promotion. Not long after, Ready to Roll and Radio With Pictures producer Peter Blake asked him to come in and record a music video special for TVNZ at Avalon Studios. Instead of just formally introducing the videos, Tee Pee wrote short raps about them, which blew Peter’s mind. “Tee Pee was utterly thrashing it up at Exchequers,” remembers Peter. “I just knew we had to use him in some capacity on TV.”

Around the same time, the educational children’s television show Spot On put together a feature on Tee Pee. Spot On host Ole Maiava had worked as a DJ at Exchequer, and he broadcast Tee Pee into living rooms around the country. Tee Pee even ended up DJing TVNZ’s Christmas party one year. He remembers arriving at Avalon and seeing a star with his name on it on the door of his green room. “That was a mean buzz,” he reflects.

DJ Tee Pee

While Tee Pee was DJing at Exchequer, Nick Mills had the idea to send him to the US once a year to source the latest music and learn cutting-edge DJ techniques. “The sole purpose of those trips was to get music, take it back, and waste everyone with my new skills,” he says. “I always wanted to be the best. It was just how I was wired.”

In Los Angeles, he befriended Carlos Mongalo aka DJ C-Los, who worked at a nightclub in the Beverly Center. C-Los had the ear of all the label reps and started giving Tee Pee spare promo records. One time when they were hanging, he let Tee Pee get on the microphone. A label talent scout happened to be in the club and offered to bring a couple of record executives back the next night to see Tee Pee perform. Afterwards, Tee Pee went out partying with C-Los and his brother and ended up sleeping for two days. “I missed that opportunity, but it was a good time,” he laughs. “I was young and reckless.”

Nick Mills and Tee Pee turned Exchequer into the place to be in. “Nick was just printing money,” Tee Pee says. For the who’s who, it was an essential spot. One evening in 1987, that included Stevie Wonder, who was in town to play at Athletic Park. The night before the concert, his band came up to the club. They were so impressed by Tee Pee that they brought Stevie up. Before he left, Stevie complimented Nick Mills on Tee Pee’s DJing. “He said, ‘That man is world-class’,” Nick says. “I said, thank you, I realise that, but of course we didn’t really.”

Two years later, Tee Pee moved to Colorado to be with his future wife, who he met on a previous trip to the States. Initially, he worked as a wedding DJ, before settling down to start a family. Prior to leaving the capital, however, he taught the basics of DJing to one final student, future Radio New Zealand recording engineer Andre Upston, who replaced him at Exchequer. The Wellington nightlife Tee Pee left behind in the capital was completely different to the one he had arrived in. A new wave of DJs was rising, and New Zealand hip hop was taking its first steps towards breaking like a tsunami wave in the mid-2000s.

Tony "Tee Pee" Pene at Dr, John's, Courtenay Place, 1985 - Rhys B collection

In Colorado, Tee Pee dropped out of DJing for a decade, until he eventually connected with the local hip hop scene and became an honorary member of two local DJ crews, Denver’s Best DJs and The Radio Bums. Back in Wellington, his old partner in rhyme, Kenny McFadden, continued playing basketball until 1996, when he shifted his focus to coaching and player development. In the late 2000s, he started coaching a promising young Rotorua player, Steven Adams, who now plays in the NBA for the Memphis Grizzlies.

Forty-odd years after he first stepped behind the turntables, the question begs itself, did Tee Pee have any idea of the impact he was having at the time?

“Nope,” he reflects. “All I knew was that I was the only one. I knew there were other rappers, but they couldn’t DJ, and they weren’t on the television. I was just a kid who came from a broken home. Once I started DJing, people started telling me I was the best, and I realised that feeling was what I had been missing. That was a huge part of it for me. I had no idea I was going to end up being a pioneer.”

In the late 2000s, Tee Pee started hearing about this incredible street dance practitioner and choreographer, Suga Pop. Suga Pop was affiliated with two pivotal dance crews, the Electric Boogaloos and Rock Steady Crew, and had danced in the music videos for ‘Beat It’ and ‘Thriller’ by Michael Jackson. When he looked him up online, he recognised his face and sent him a message: “Hey man, did you come up in New Zealand?” Suga Pop replied. Sure enough, that familiar face was his old mate Steven from The Funkateers. But how did he get from smashing disco competitions in Wellington to dancing in Los Angeles and New York as Suga Pop? Well, that’s a story for another time.

--

Interviews and research conducted by Phil Bell aka DJ Sir-Vere and Martyn Pepperell

Mai FM: Aotearoa Hip Hop podcast