In the 1940s New Zealand jazz fans organised jam sessions for musicians at which the fans could be audience and witness to what was usually a private musicians’ affair. Reported in local jazz magazines Swing! and Jukebox: New Zealand's Swing Magazine as "official jam sessions", these jam sessions were structured around both the musicians and fan based activities. These activities usually included listening and discussing records, and mini-lectures or discussions and debates about a particular jazz related topic.

The “official” jam sessions in 1940s New Zealand were in some ways similar to the public jam sessions in places such as New York City of the same period, but also different, as these were not held in commercial venues such as nightclubs, nor were they a commercial venture. Arranging and organising jam sessions in this manner appears to be very unusual in the context of global jazz culture and fandom.

It is unknown exactly when this type of jam session was conceived. Swing! Indicates that the first “official” (fan organised) jam session took place on November 24, 1941 in Wellington. However, such sessions might have also occurred in the late 1930s as newspaper reports on swing and rhythm clubs note what appear to be similar types of events within the context of club activities. For the sake of simplicity, this article focuses on the “official” sessions in the 1940s because the existence of Swing! and Jukebox, meant that such sessions were reported on in depth.

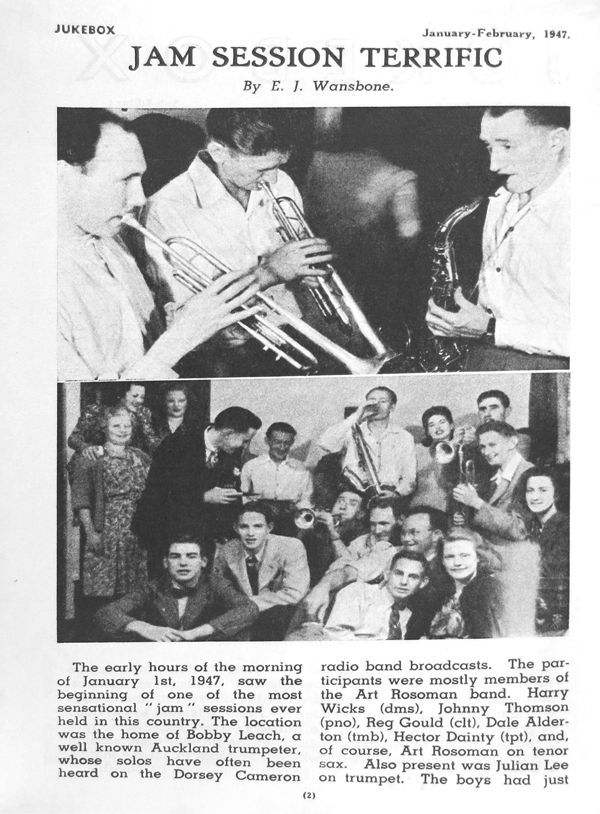

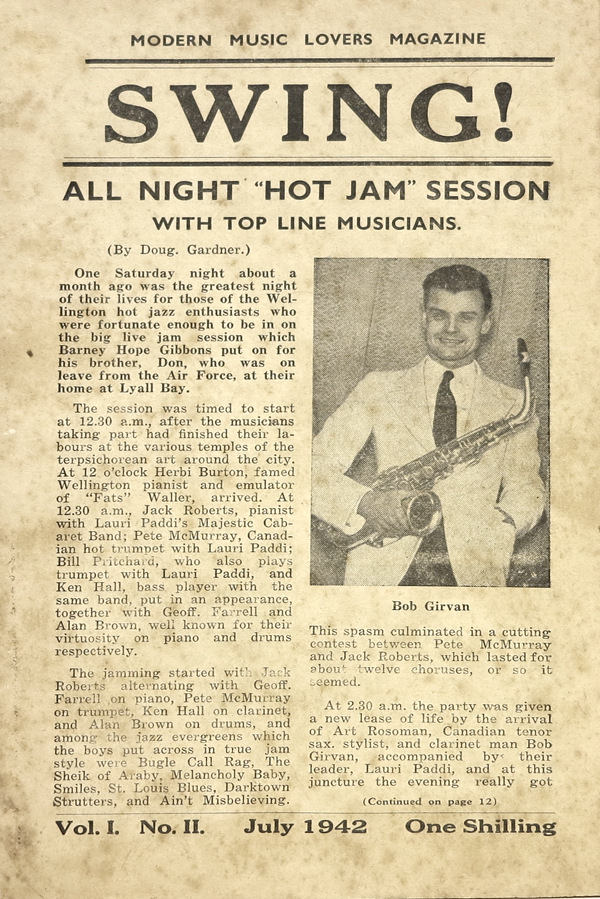

It appears that fan organised jam sessions became a regular feature on Wellington's jazz scene from late 1941. It is unknown whether these types of jam sessions were occurring anywhere else in New Zealand, as Swing's local content was mostly Wellington focused. However, it seems likely that swing clubs in other main centres embraced this format. Certainly the concept had spread to other centres by the middle of the decade as Jukebox magazine reports such events in other centres in 1946 and 1947.

Why these jam sessions were “official” is unknown. None of the reports state why these sessions were “official” as opposed to the ones held during the swing club meetings. Possibly the jam sessions discussed here were termed “official” because they were closer to the informal private jam sessions that musicians held among themselves, and these sessions were (theoretically) not as structured or constructed as the ones held at swing club meetings. Perhaps in the eyes of the fans and columnists this made the experience a more authentic one: as if the audience was witnessing a truly private jam session.

The “official” jam sessions were invitation-only affairs held at a fan's house, or in a venue such as a church or community hall that was hired for the night. The host would invite all local jazz musicians, and any other jazz musicians touring the area, and then invited members of jazz clubs, and other jazz fans to be the audience. The sessions began at various times of the evening, some early (8 or 9pm), some later (closer to or after midnight). Some sessions, especially the ones starting late at night, were just that, an informal jam session that happened to have an audience. Some were jam sessions that had some organisation and structure – this might include a partial or full set listing, or certain combinations of musicians playing for certain amounts of time or after certain hours. This type of arrangement was often a result of when gigs began or finished. And still other jam sessions – especially those that began early in the evening – had an entirely different structure that involved more than jazz musicians jamming.

In this last type of jam session, the first part of the evening before the performing musicians arrived consisted of fan activities, such as playing the latest acquired, or favourite, jazz records. Accompanying these record recitals were discussions of the recordings that were often quite wide ranging, including research into the arrangements and soloists, or even discussions about recording venues and techniques. Other presentations might be on specific musicians, or the evolutions of bands or styles. Or there might be a presentation on a specific subject relating to jazz, such as the one given by pianist Vora Kissin on the effects of marijuana on jazz musicians’ abilities.

There were also musical games and quizzes to amuse the audience. This portion of the evening would usually last until the musicians began to arrive from their gigs. The arrival of the musicians would signal a break in proceedings for supper, enabling the musicians to set up their instruments and to socialise with fans and the other participants.

After the supper break, the musicians would begin the jam session. From this point the structures diverge. In some sessions it would proceed as a normal jam session, where the musicians chose tunes, or took requests from the audience for pieces to jam on, and decided who was going to play when. In other structures there might be some formal construction to the session as mentioned above with certain combinations of musicians or structured sets.

While the presence of an audience at a jam session was not unheard of, an important difference here in is the construction of the audience at these official jam sessions. They were not paying customers at a club or concert, nor were they all musicians who were there to relax after a gig (or to line up the next gig). They were mostly fans who had been specifically invited to attend the session. A sort of elite audience, whose invitations relied on the social cachet of being a jazz fan, but whose in-depth knowledge of jazz proclaimed that they were true fans.

The presence of a non-participant audience gave these jam sessions the atmosphere of a gig. However, the main difference was that this audience was not engaged in socialising or dancing, as was common at this time, instead they were concentrating on the music. For musicians who mostly performed in cabarets, dance halls, and for company balls this attention would have been gratifying. For the audience too, this situation would have been gratifying as they were in a position where they able to concentrate on the music and not be thought of as anti-social!

Little was written explicitly about the fan/musician interaction at jam sessions in the published reports, however there were occasional remarks about the fans and musicians’ appreciation of each other. The interactions between fans and musicians at the jam sessions were possibly not unlike those at the jam sessions held at swing club meetings. However, they were probably less formal and more intimate, as when the musicians were not playing they would be part of the audience. The barrier between musician and fan, entertainer and audience member, was diminished and they became comrades in the common pursuit of jazz.

As a result of these interactions, different standards of behaviour came into play with the notable New Zealand reserve giving way to an overtly enthusiastic response. This included applauding individual solos (something that New Zealand audiences in commercial settings did not do at that time), and vocal encouragement to soloists. Reports of jam sessions indicate that the fans raved about the music, especially the improvisation that occurred during the course of the session, and emphatically demonstrated their appreciation to the musicians. Also remarked on were the discussions between fans and musicians about jazz that occurred during changeovers in performers, and at the end of the session while people were leaving.

Breaking down the barriers between musicians and fans was important for the development of a national jazz community. Through these jam sessions musicians and fans were able to connect to each other on a level that was not possible at a commercial gig. There was a certain level of familiarity between the two groups at swing club meetings, but these official jam sessions appear to have extended that familiarity to create camaraderie between fans and musicians.

Additionally, while musicians had long had informal and formal networks between towns, assisted by an active musicians union, fans had no such a network to find other fans. The individual fan clubs appear to have had very little connection to each other so finding other clubs and fans was mostly by word-of-mouth. These official sessions and their reports helped fans to connect with other swing clubs, and like-minded individuals.

These connections boosted the development of a New Zealand jazz community in various ways, but perhaps most importantly the connections between musicians and fans made at the official jam sessions helped to advocate New Zealand jazz and the local jazz scene. The official jam sessions aided this advocacy in two ways.

First, hearing jazz musicians play without the strictures of dancing (which limited the time for each piece and the amount of improvisation included) gave local fans a new perspective on what New Zealand jazz musicians were capable of. This was particularly important because of the disjuncture between the carefully produced artistry that they heard on records from overseas, and the New Zealand day-to-day reality of playing for dance gigs. New Zealand fans were too often inclined to believe that local jazz could not possibly be as good as that found in other countries. It is particularly interesting to see in reports of these official jam sessions how often the columnists note that there are real jazzmen in New Zealand: as if they had not been expecting the quality of jazz that they heard on the night. This realisation was an important factor in developing the local jazz scene, and creating a community that supported local jazz musicians as well as those from other countries.

Second, the official jam sessions also helped to extend a network among fans. This led to a closer connection throughout the fan community so that when they travelled they could find other jazz fans and clubs. This also led to fans becoming more familiar with jazz musicians from outside of their home regions; again an important factor in advocating New Zealand jazz, and in developing the local jazz community.

The official jam sessions were a combination of fan activities (record recital and analysis), private gig, and musician's jam session. However, while these activities all occurred elsewhere, the fan-organised official jam session offered a more intimate atmosphere, which was not possible in a large club meeting. The intimate environment of the official jam sessions led to greater interaction between the fans and musicians. These interactions helped to create a more involved fan advocacy, which, in the 1950s would contribute to the success of jazz concerts, and the rise in non-dancing venues for jazz.

In the context of New Zealand, the official jam sessions contributed to the appreciation and musical comprehension between musicians and fans. They also contributed to the stature of local musicians in a jazz community that mostly looked to recordings (primarily from the United States) for examples of good jazz. These “official” jam sessions were a significant factor in the development of the jazz community and the culture that surrounded jazz in New Zealand during the middle of the 20th century.

–

Thank you to Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries