Hello Sailor’s debut album had gone gold and they had two Top 20 hits under their belt. The logical next step was Australia – that’s what every other NZ rock band had done. Instead, they went straight to Los Angeles in a bold bid for international success. Jeremy Templer was with them in LA for three months and tells the story.

October 29 1978

I remember the day quite clearly, even now: I’ve just arrived in LA and I’m with Hello Sailor manager David Gapes, who’s driving, the sunroof down, radio on. David’s son Richard is with us, and Lisle Kinney, the band’s bassist. The sunshine’s so bright it burns your eyes. I don’t have sunglasses with me but it doesn’t matter. It’s my first time in LA, my first time in the States, and everything’s good until we hit a massive traffic jam, all six lanes of freeway traffic going nowhere fast.

Cut to the car radio, where one song blends into another with no ads, no interruptions. This was revolutionary programming for its time. When other stations were playing Donna Summer and The Bee Gees, K-ROQ would play new songs by Blondie, Elvis Costello, The Clash, B52s and Devo, mixed in with classic rock from Aerosmith, Cheap Trick, KISS and Led Zep. Hard rock, punk and new wave. And somehow it all worked.

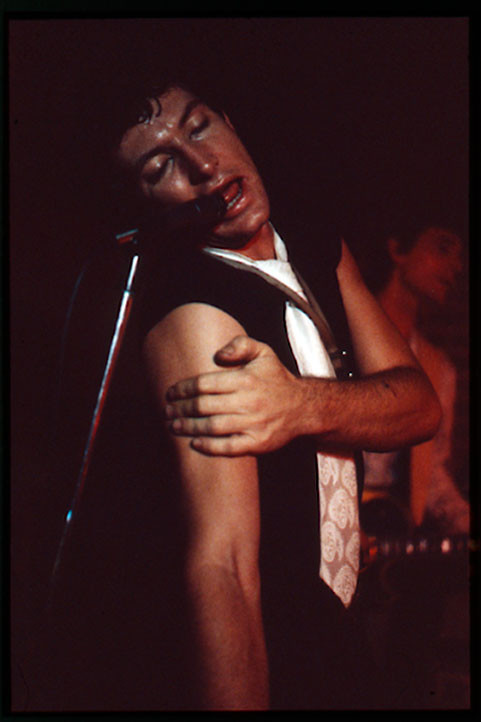

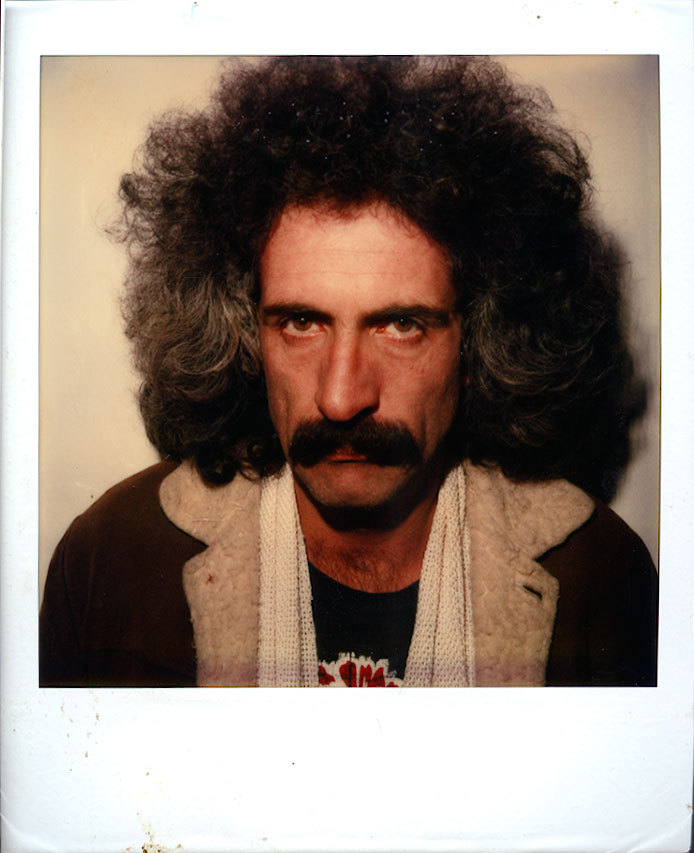

Graham Brazier at a private Christmas party.

We weave our way through traffic, eventually picking up speed and turning into Sunset Strip with its monstrous look-at-me music billboards (one, a roller-skating Linda Ronstadt promoting her new Living In The USA album). Back then a billboard on Sunset Strip promoting your new record meant you’d really made it; fast forward a few years and all that money would instead go into producing music videos.

Turning up Laurel Canyon Boulevard, David points out the Canyon County Store (a one-time hangout for artists like Joni Mitchell, David Crosby, Graham Nash and The Doors). We continue past the ruins of the Harry Houdini mansion, turning up Lookout Mountain Ave and into Wonderland Ave.

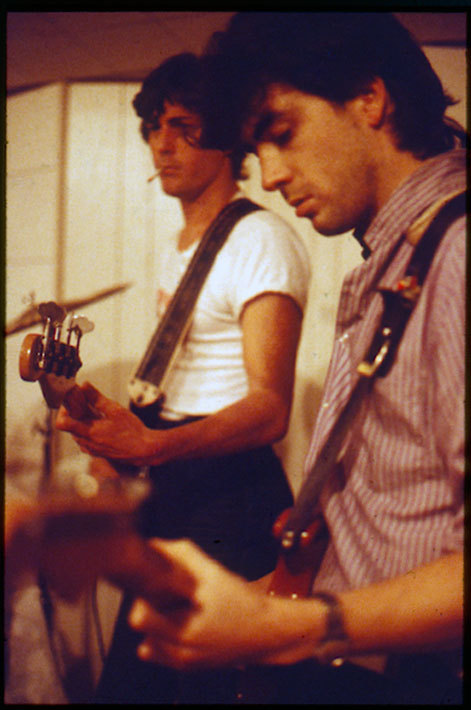

Lisle Kinney and Harry Lyon rehearsing in LA.

8888 Hollywood Hills Road

Hello Sailor lived at this address from the end of August 1978 to mid-February 1979. The house became well known to musicians, roadies and girlfriends, along with most of Hollywood’s wannabes. Others, fearing its reputation, simply stayed away.

Pat Crowe (“Tiny Tina”), a one-time tour manager for the Paul Dainty Corporation, kept house. There were just three bedrooms but often 15, 20 or more staying there, so the library, studio, loft room, pool and garden sheds were all turned into guest rooms.

Among the entourage was Peter Adams, the band’s graphic designer, whose distinctive posters announced each new show. I was there as the band’s unofficial photographer, taking shots of the band at pretty much every gig.

Lisle Kinney and Harry Lyon rehearsing in LA.

Short on space, even the dog house near the pool would be used as sleeping quarters. And after a week or two on the living room couch, I was the one who got the dog house.

Strange Days

At the time, it was New York, not LA, that was on the rise. Clubs like CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City were home to new acts like Talking Heads, The Ramones, Patti Smith, Blondie and Television. Rap, too, was growing in popularity.

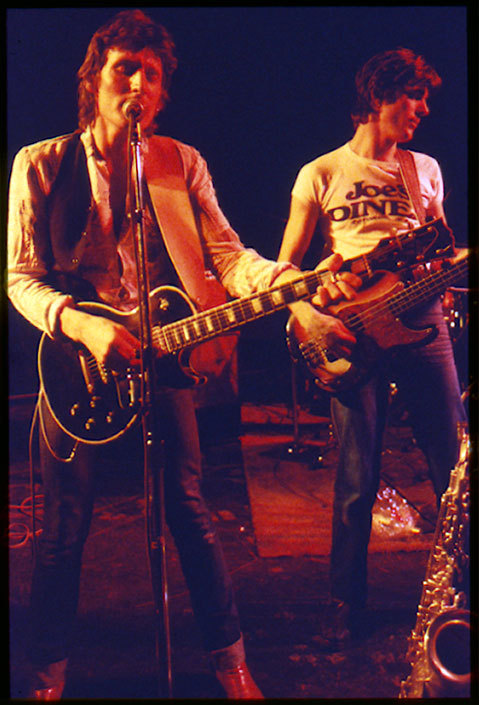

Ricky Ball at The Wooden Nickel.

In contrast, LA’s music scene back then was – in a word – confused. The nexus of rock music earlier in the 1970s when singer-songwriters were all the rage, LA had yet to make sense of punk and new wave, and disco dominated the airwaves. This made it a difficult time to be a talent scout in LA. But it was a tough time for rock bands too.

To get noticed you needed to play Doug Weston’s Troubadour and The Starwood, and eventually you got to play The Whisky a Go Go on Hollywood’s celebrated Sunset Strip. But to play The Roxy, the other big club on the Strip, you had to have made it already.

Backstage at The Wooden Nickel.

Hello Sailor’s first big gigs in LA were at the Troubadour in early October and at The Starwood with Mother Goose, shortly before I arrived. David once told me that all the record company people were there at their first Starwood gig. And that they’d made a rookie mistake in relying on the club’s PA: the sound wasn’t what it should have been. The plan had been to blow everyone away; the hope was that they might even be signed that very night. Instead, everyone left saying the band weren’t bad.

It meant several more gigs at The Starwood and many more at other clubs, trying to get record companies interested. While Hello Sailor did venture outside Hollywood, they didn’t go too far afield. They stuck to a circuit that included Madame Wong’s in Chinatown, The Rock Corporation in Van Nuys, The Sweetwater (Redondo Beach), The Golden Bear in nearby Huntington Beach, and The Wooden Nickel in Lancaster.

Graham Brazier at The Troubadour.

Mother Goose, meanwhile, had been in Hollywood since June that year. They had their own recording studio and a record deal they weren’t too happy with, and left soon after for New York.

Break On Through (To The Other Side)

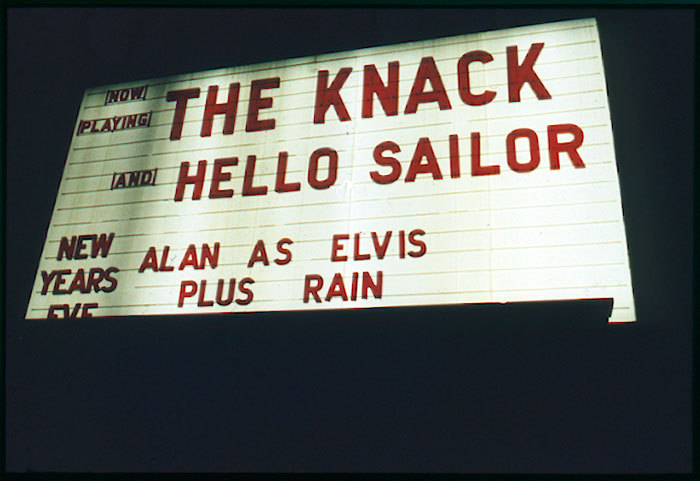

Some gigs were packed solid, others far from it. But by November that year things were finally starting to happen. The Knack – then the hottest unsigned band in LA – had taken a liking to Hello Sailor, and gave them opening gigs at The Whisky and The Troubadour. Sailor also opened for The Kats, another band on the up. The Kats had left Minneapolis the year before (they were told no label would sign them if they didn’t).

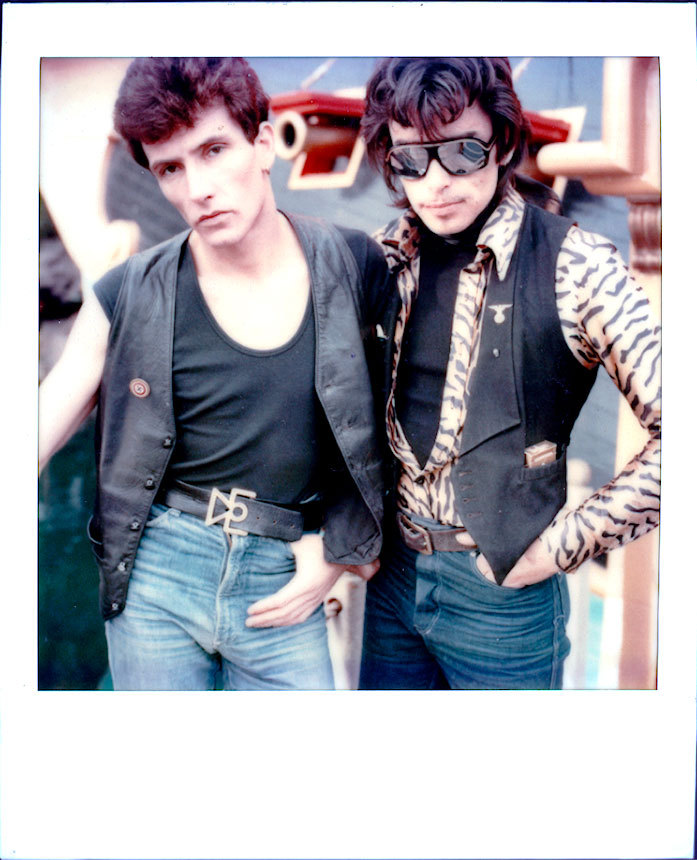

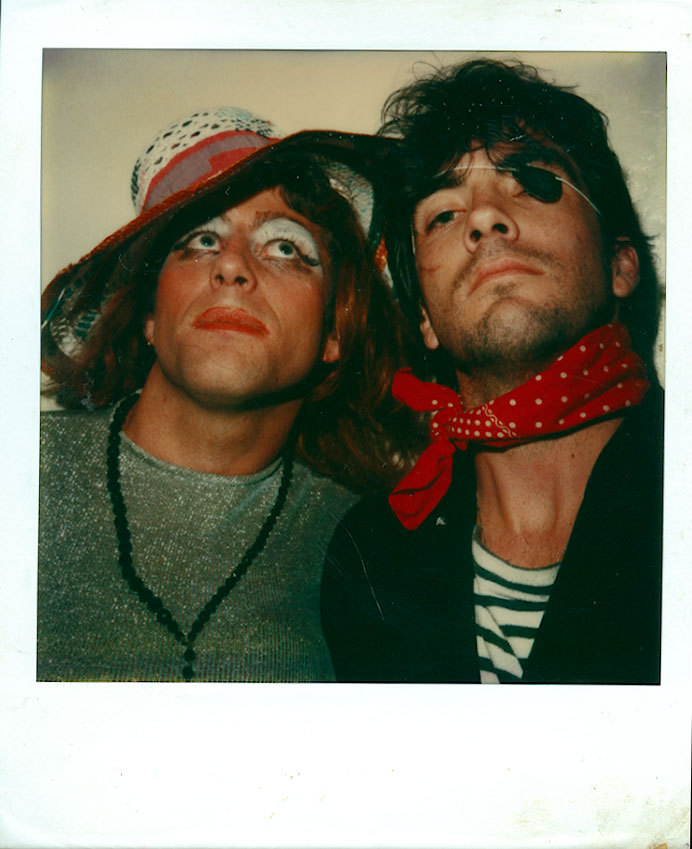

Dave McArtney and Lisle Kinney at a private Christmas party.

The Doors’ manager Danny Sugerman, later the co-author of the Jim Morrison biography No-one Here Gets Out Alive, was a frequent visitor to the Hello Sailor house. And Ray Manzarek, keyboard player for The Doors, got interested in the band too. Manzarek, at the time the house producer at Elektra/Asylum, actually joined Sailor onstage at The Whisky, playing with them on ‘Blue Lady’ and ‘Dr Jazz’.

Graham Brazier and Hello Sailor's graphic designer Peter Adams.

Manzarek also asked Hello Sailor’s Graham Brazier if he’d join The Doors on a tour to promote An American Prayer, the posthumous record release of Morrison’s poetry. There was to be a nationwide tour, each gig closing with some of the group’s better-known songs. Manzarek wanted Graham to sing the songs made famous by Morrison – knowing what that would mean for Hello Sailor, he turned the offer down.

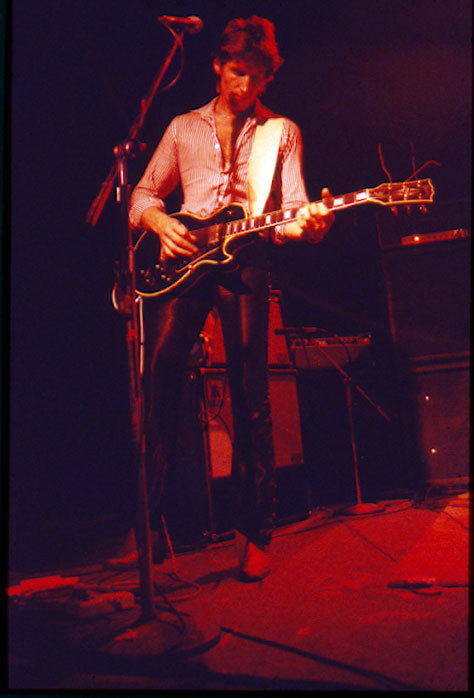

Dave McArtney at The Whisky.

One of Hello Sailor’s roadies, “Mad Dog”, introduced the band to Earl Slick: “Don’t call him Earl, he’s Slick". Slick, who was David Bowie’s guitarist after Mick Ronson’s departure, would produce some demos of the band.

Weird Scenes

One day Dave McArtney turned up at the house, a pair of boots in his hands. A Laurel Canyon house rented by Keith Richards had just burnt to the ground and, picking through the ruins, Dave had found the boots, Keith’s boots. Among other booty, he also came back with Keith’s notebook (which later provided the Pink Flamingos’ song title ‘Dying in Public’). Someone else got the real gold though – a cassette tape recording of Keith playing guitar and trying to write some songs. Listening to the tape, there were frequent stops and starts as Keith’s session was interrupted (by Mick at one point, dropping in to see how things were going).

David Gapes.

Then there were the times Dragon visited the house, both occasions bookending a tour with Johnny Winter. They played The Whisky in LA, and the mismatch was evident even then – Winter’s blues-loving audience had no time for the band. Things came really unstuck in Texas, though, with the audience showing their appreciation with a hail of beer bottles (as they had for the Sex Pistols earlier in the year).

Show me the money

For their first gig at The Rock Corporation, Hello Sailor were paid $30 (enough to pay for a haircut). When they next played there, they were paid $125 – still a fraction of what they had earned when playing bigger gigs back home in Auckland. (At the time the NZ dollar was worth slightly more than the greenback.)

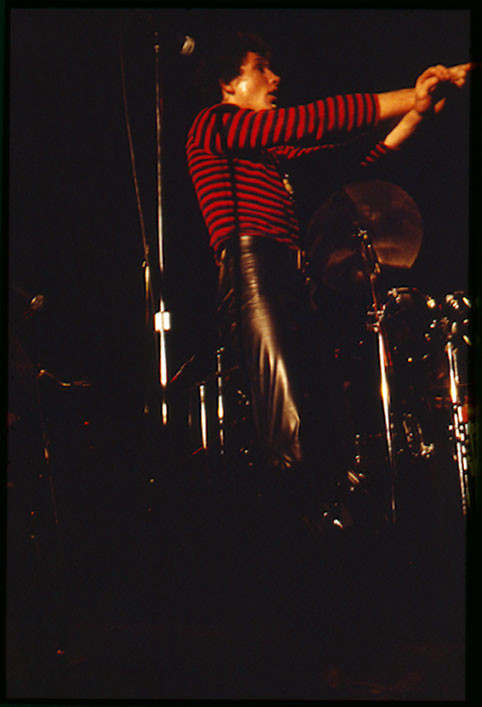

Graham Brazier at The Whisky.

Back in the day, before the 1977 Rum & Coca Cola tour in New Zealand had set them on their way to become “New Zealand’s best rock band” (a claim they used to secure favourable USA visas, and get sponsorship from Air New Zealand), they didn’t have all the additional expenses to pay. There were no roadies, there was no manager – they did it all themselves.

A leaner crew might have toughed it out in LA long enough to secure that elusive record deal, but no-one could guess whether that meant another six months or another year or two. By February they’d run out of money, and it would be a few months more before the record label scouts would be back to see who was worth signing.

Graham Brazier at The Whisky.

Ship Of Fools?

Young as everyone in the band was, Hello Sailor weren’t prepared for the invitations to excess that came with the move to LA. And, in hindsight, it may not have been the smartest of moves to take a rock band well-known for its indulgences, transplanting them into such a party town and letting them have everything they wanted. But, what if?

If the band had quickly landed a deal as Gapes had hoped, this story might have been a very different one. Instead, Sailor returned to New Zealand only to find the local scene had changed. With more competition from bands like Th’ Dudes, they weren’t able to make as much money as they thought (and not enough to get back to LA as planned). And in the end they did go to Australia – but that, as they say, is another story.

In rock mythology, the critical ingredient in eventual success is luck. A would-be actress gets lost en route to her audition, stumbling into the office of a music publisher who asks if she can sing. A group of buskers is spotted on the streets of Milwaukee and invited to open for a hit UK act. An agent’s secretary makes her boss listen to a discarded demo tape because, well, the musician looks cute. A band from the Antipodes ups and moves to Hollywood, and a Rolling Stones roadie sees the guitarist is wearing Keith Richards’ missing boots. All “true” stories that led to stardom, except the last (Melanie, The Violent Femmes, Jackson Browne).

Ricky Ball and Harry Lyon - Halloween!

For Hello Sailor, LA was supposed to be a shortcut to a major record label deal, avoiding the rigours of constant touring that had ultimately brought other bands US success. There were meetings with record companies, there was interest in the band and, but for luck, it might have happened just that way.

True, Sailor didn’t have a ‘My Sharona’, a song destined to be a hit, even before it had been recorded. But then most bands don’t. The highlight of their act at that time was ‘Son of Sam’, near perfect but for the fact that serial killer David Berkowitz had been arrested and convicted a year earlier.

Waiting For The Sun

There were a couple of thousand bands competing in LA for a record deal that year. And only a few (The Motels, The Dickies and 20/20 among them) got signed.

Meanwhile, what happened to the bands Hello Sailor used to open for? The Knack’s story is well-documented: in late 1978 there were 13 record labels in a bidding war to sign them. Capitol won out, releasing the Mike Chapman-produced debut Get The Knack in 1979. Said to be the fastest-selling debut LP since Meet the Beatles, it sold five million copies that year. ‘My Sharona’, the first single from the album, topped the USA charts for six weeks and sold a million copies, becoming a hit worldwide. The group broke up in 1981. That, at least, is the official story.

There were rumours, however, that The Knack signed with Capitol earlier in 1978, even before the supposed bidding war in November. This story has it that the LA gigs – and the whirlwind of record company interest they ultimately precipitated – were just a clever charade, intended to provide the group with some much needed street credibility. That may be true: after all, The Knack weren’t punk, nor were they self-taught musicians yet to master more than three chords. Vocalist Doug Fieger had come close to success with Sky (there was an album, recorded in London, and shows opening for Traffic), while the drummer and guitarist had been session musicians, playing with Three Dog Night among others.

And The Kats? They finally struck a deal with MCA’s Infinity Records in 1979. What should have been a good luck story turned sour, though. The record company went under, the group disbanded, and the album they’d completed was presumed lost to the world. That album, Get Modern, was finally released in 2012, more than 30 years later.

(This is) The End

By the time Hello Sailor vacated the Hollywood Hills house in mid-February, David was no longer the band’s manager. He’d lost everything he had in bankrolling the venture, including his house. Yet it’s fair to say that without him there wouldn’t have been this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity – no-one else would have taken such a gamble.

I carried on to San Francisco, New York and London, photographing other bands (among them The Cramps and The Birthday Party) and documenting different scenes. I returned to LA a number of times, but it would be more than 30 years before I moved back to New Zealand.

And what of the house that for six months had been home to this long, mad, exhausting party? The realtor said she thought she had a taker: one Dr Timothy Leary.