Many of the best-known images of New Zealand pop bands and solo acts from the 1960s emerged from the camera of a Lower Hutt photographer and jazz bassist, Barry Clothier. With his contemporary and friend, photographer Sal Criscillo, Clothier was on speed dial at HMV (NZ) Ltd when the company needed promotional photos, record covers or candid shots.

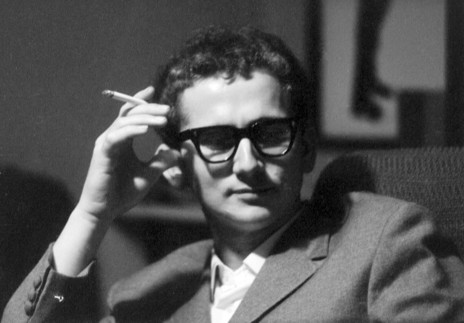

Barry Clothier, photographed in the mid-1960s by Sal Criscillo.

Among the acts he photographed were The Fourmyula, The Simple Image, and solo acts such as Dinah Lee, Maria Dallas, and Mr Lee Grant. He captured musicians at work in the studio, teenagers dancing to them in local halls, and at play in clubs such as The Place. For promotional photos, Clothier worked hard to make a session different, with a range of locations as limited as his budget.

Clothier donated his negatives and contact sheets to the Alexander Turnbull Library before his death, aged 77, in 2017. On this page are 10 images enlarged from his contact sheets. These, and many other images, were featured in The Simple Image – a temporary exhibition at the National Library in Wellington, which opened in July 2021.

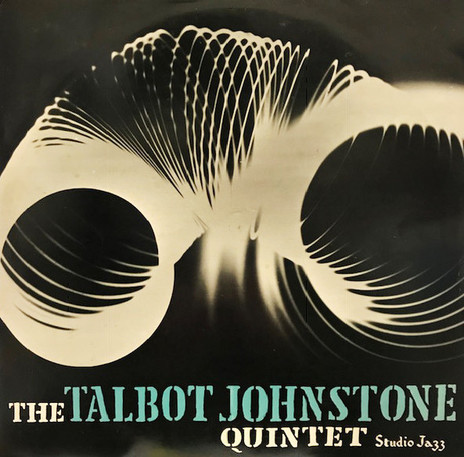

Born in 1940, Clothier grew up in Epuni, Lower Hutt. He trained as a teacher, but became a linesman working for the Post Office. When he was 20, he played bass as part of the Talbot-Johnstone Quintet, a jazz combo influenced by Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and Miles Davis’s just-released Kind of Blue. On a Sunday afternoon in April 1961 the quintet recorded an album at the Studio Jazz Club, above the Regent poolroom in Wellington.

Studio Jazz - Scene 1, The Talbot Johnstone Quintet (Studio Jazz, 1961)

The group had an unusual frontline of two clarinettists, both named Bruce (Talbot and Johnstone also played saxophones); on piano was Dave Fraser, then just 19, and the drummer was Garry Kennington. The seven tracks are standards old and new, interpretations of Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, and Milt Jackson. Talbot described the scene: “It was the kind of depressing, grey, overcast Sunday that only Wellington and Greymouth can achieve … the kind of day that makes lunk-heads ponder the hereafter and write beat poetry and the sensitive ones think seriously of crawling back into the sack.”

By the mid-60s Clothier was moving in photographic circles; among his friends was John B Turner, the founder of PhotoForum (see below). Sal Criscillo was shooting for ad agencies, and another key contact was Warwick Woodward, a legendary record collector who was the fledgling music industry’s go-to advertising man. “We got the work through our connections with HMV’s producers, and [HMV sales manager] Graham Feasey,” recalls Criscillo, whose simultaneous body of work for the company was just as extensive.

“We finished up shooting a variety of HMV acts and overseas visitors. We’d get a call saying, ‘Count Basie or Thelonious Monk is at the airport, we’d photograph them and drive them back to a hotel. Or we’d go back to the jazz club. Soon we got out of the paparazzi situation into professional shoots. Nothing was paid for, we just got a few complimentary tickets or LPs. Part of it was just the excitement.

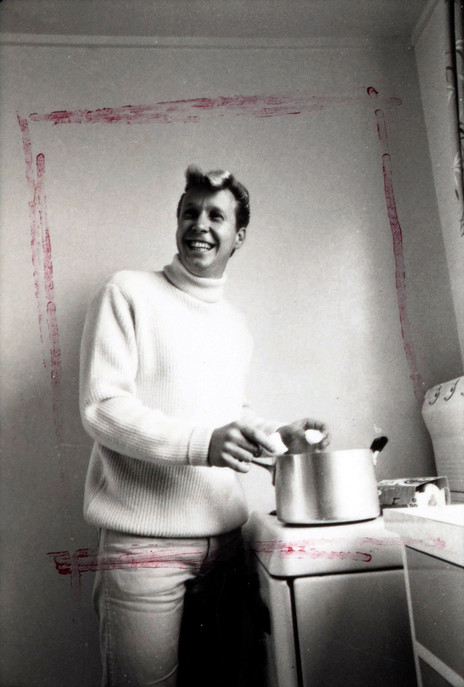

Lew Pryme boils an egg. - Barry Clothier, from a 35mm contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-21, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

“Any briefings were light. We just went out and go to play for an hour, and take the bands out into the fresh air. In the first year, I was freelance, and an ad agency was quite happy for me to use their studio.”

Criscillo then got his own studio space, sharing it with Clothier for a year, before the latter hired some space on Courtenay Place.

“Barry was a loner,” says Criscillo. “He was one of those guys who was inside himself. Like all photographers he was an observer, not a partaker. He was serious about photography. He had come through the camera clubs and government work. He had a very structured approach. So he liked the freedom [with the HMV commissions], not having the client leaning over him. He loved that kind of music more than me: he was into pop as well as jazz.”

HMV producers such as Howard Gable, Peter Dawkins, and Alan Galbraith would contact the photographers when acts were recording in the studio, or performing at the Town Hall or Opera House. “Whatever we photographed, we sent proofs to HMV, and that was the end of it,” says Criscillo. “We liked the openness, and the demand was there. We were quick, and it was loads of fun.”

A close friend of Clothier’s from the 1960s till the end was the music retailer Colin Morris, who arrived from the UK to Wellington in 1963, aged 17. “Through Barry and his wife, I met Sal and Warwick and became part of the camaraderie of music people,” he says. “They pointed me in directions I wouldn’t have thought of – Charlie Parker, Ben Webster – I owe them a huge debt.”

Morris remembers Clothier as a film buff, and together they would go to the National Film Unit to see unreleased films, and attend the film festivals together, watching several in a day. “He photographed for HMV for a short period,” says Morris. “He didn’t talk about the bands much. But I do remember him telling me about photographing a Fourmyula album cover.”

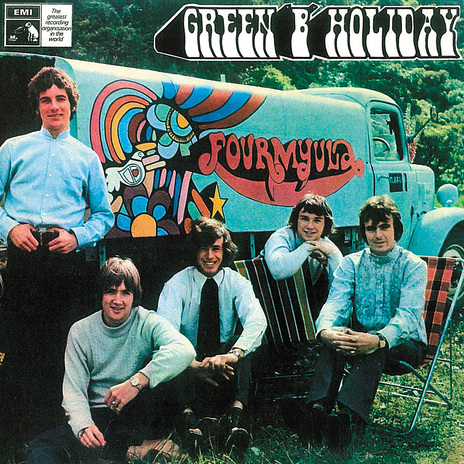

The Fourmyula's Green B Holiday (1969); photo Barry Clothier, artwork Lyn Bergquist.

Clothier and artist Lyn Bergquist had designed the cover of the Fourmyula’s self-titled debut together, and their next assignment was the cover of the band’s concept album Green ‘B’ Holiday (1968). The main prop was the band’s touring truck, a 1949 Commer which had canvas sides. “Lyn spent all day painting a psychedelic-style graphic on the side, and by the time he’d finished it was too late for a photograph. That night it rained, so he had to do it all again on the other side of the truck.”

From the 1970s, Clothier concentrating on advertising and educational photography, often on contract to government departments. He also had a sideline as a specialist photographer of pets. But his work photographing musicians has become timeless.

The Avengers outside HMV (NZ) Ltd, Wakefield St, Wellington (near Te Papa). The humble headquarters of the New Zealand branch of the world's "greatest recording organisation" is at odds with the threads of New Zealand's best-dressed band. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-2-42, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

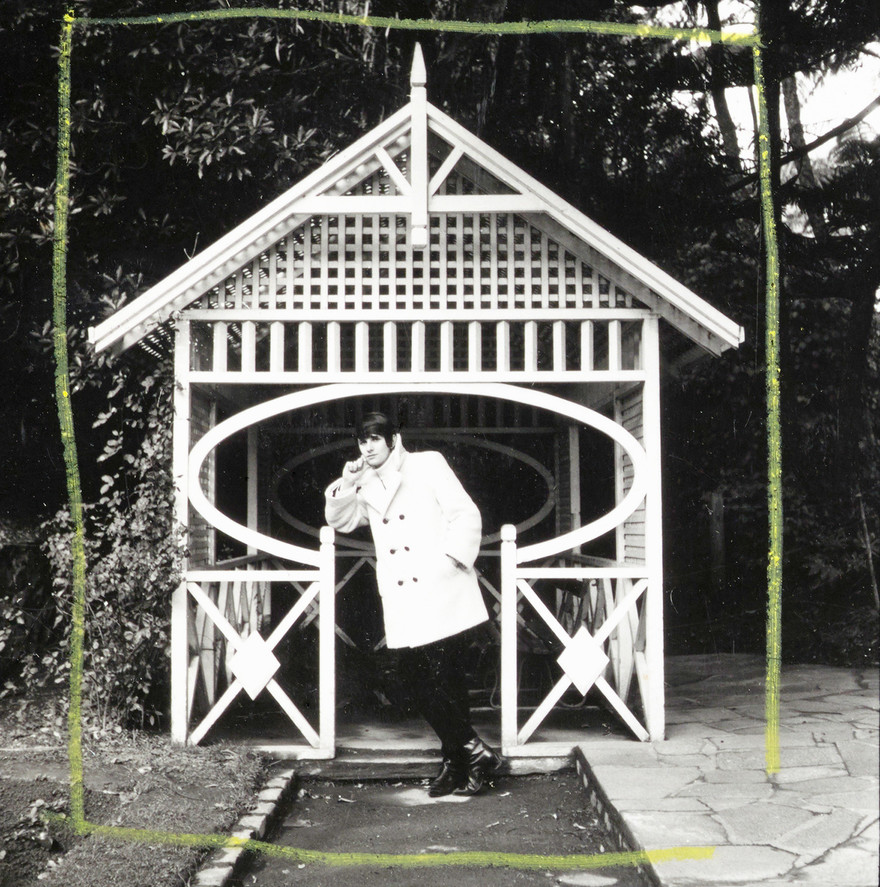

Mr Lee Grant, at the Botanic Gardens, Wellington, 1966 - a favourite location for HMV promo shots. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-16, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

The Shevelles at the Botanic Gardens, Wellington, July 1969 . - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-2-64, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

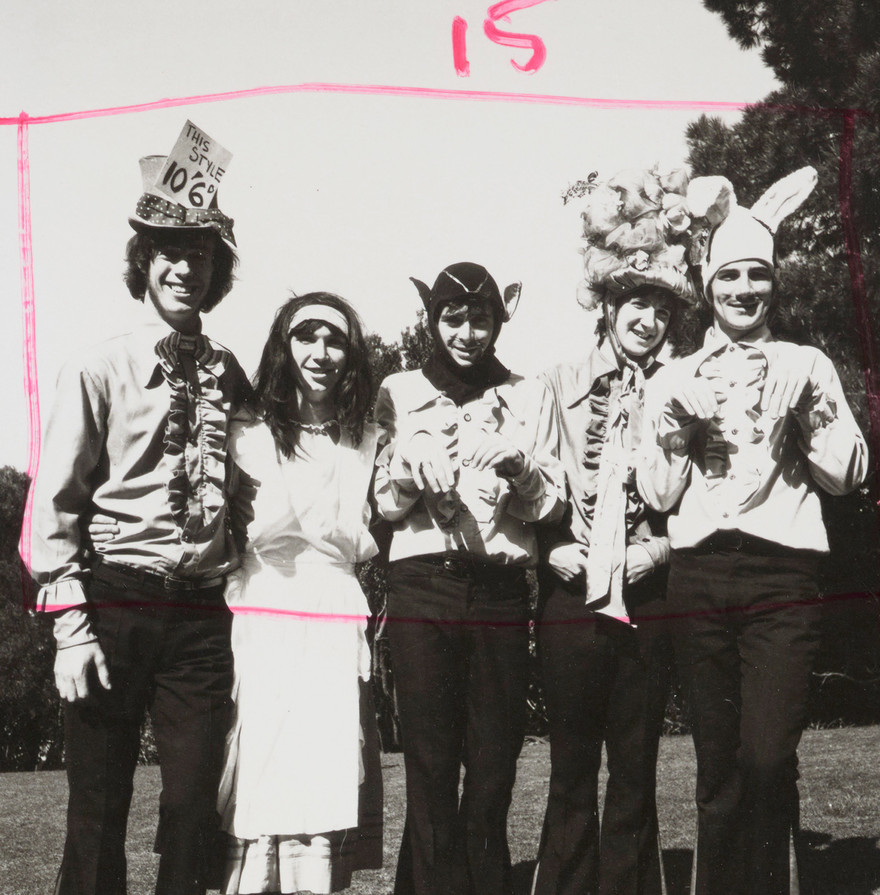

The Fourmyula goofing off Lewis Carroll-style to promote their 'Alice is There' single, September 1968. From left: Wayne Mason, Ali Richardson, Martin Hope, Carl Evensen, Chris Parry. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-2-44, Alexander Turnbull Library

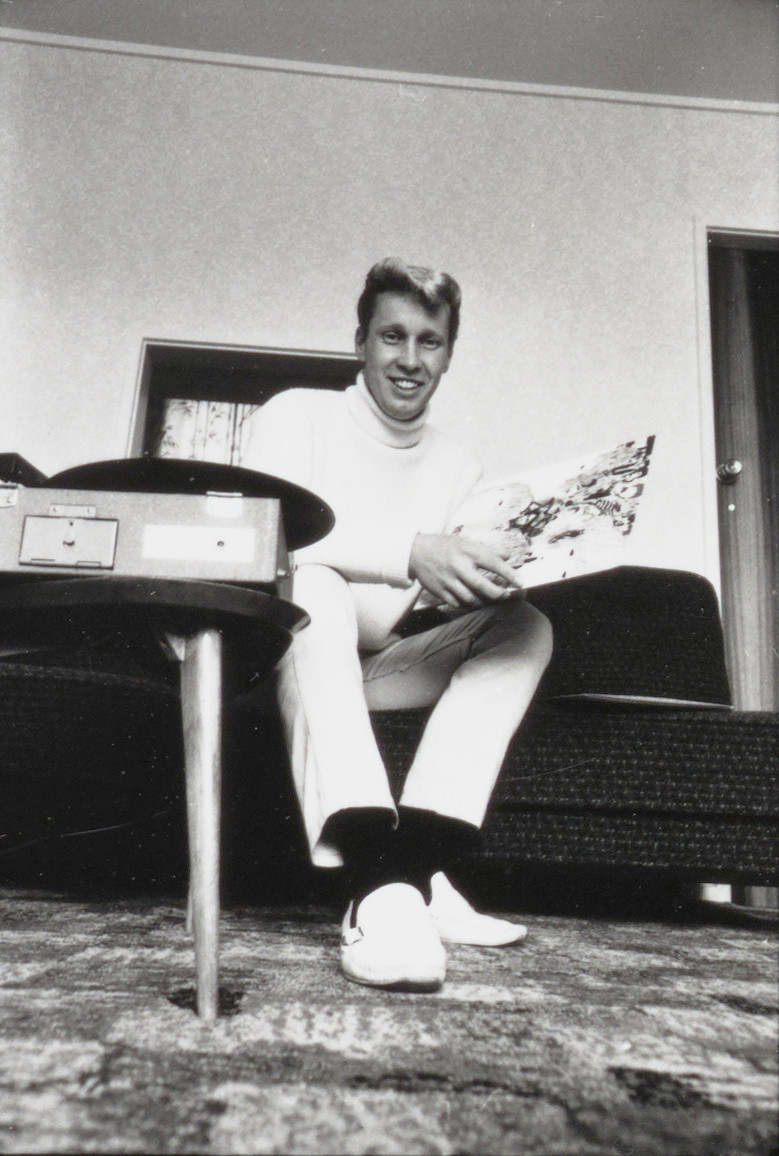

Lew Pryme enjoys the Beatles' just-released Revolver, September, 1966. - Barry Clothier, from a 35mm contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-21, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

The Bitter End, April 1967. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-52, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

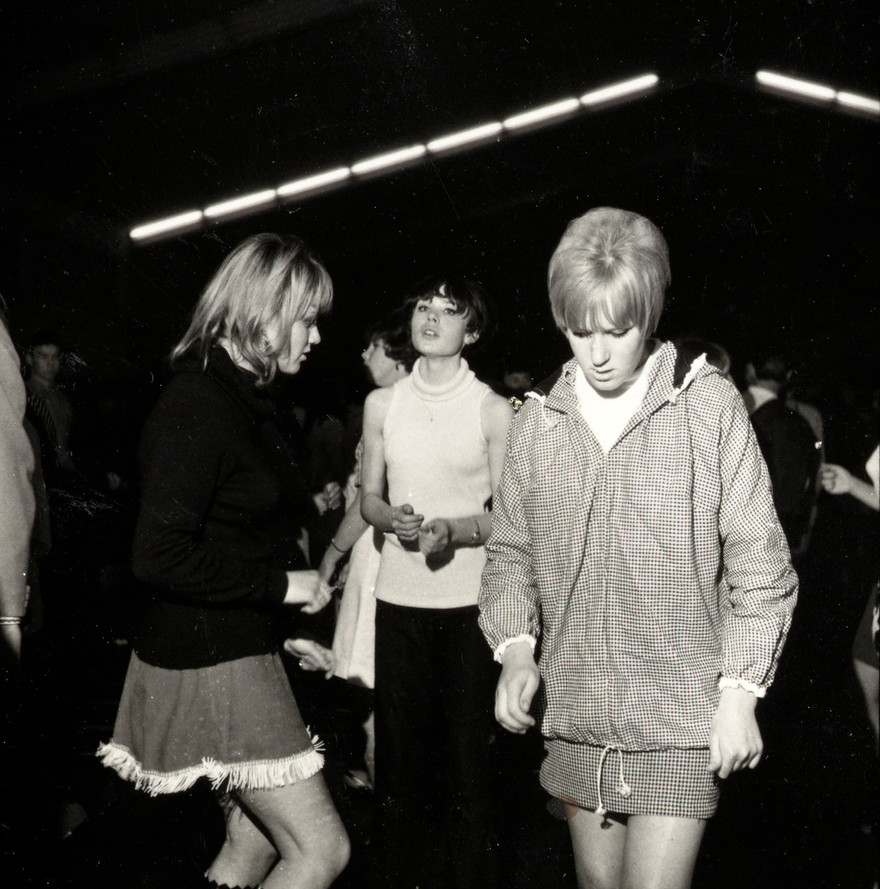

Dedicated followers of fashion, dancing to the Dizzy Limits at a Hutt Valley Youth Club jamboree, October 1966. These were regularly held at the Horticultural Hall and the adjoining Town Hall in Lower Hutt. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-33, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

The Simple Image with Gerry Merito, formerly of the Howard Morrison Quartet, Wellington, June 1967. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-60, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Gerry Merito, formerly of the Howard Morrison Quartet, Wellington, June 1967. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-60, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

The Supernatural Blues, in the shadow of Premier Richard Seddon, Parliament grounds, Wellington, March 1969. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-2-57, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Dancing to the Dizzy Limits at a Hutt Valley Youth Club jamboree, October 1966. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-33, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

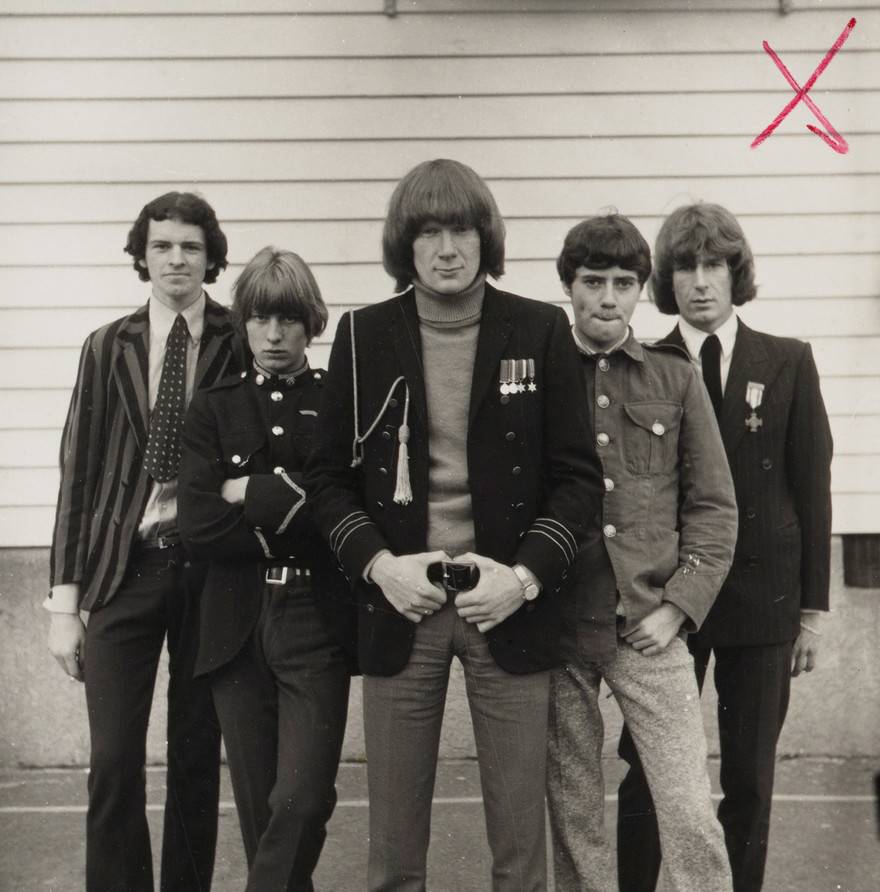

Tom Thumb (Rick White, centre), Wellington, June 1967. - Barry Clothier, from a contact sheet, PAColl-7031-1-59, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

--

John B Turner of PhotoForum writes: Barry and I met at the Upper Hutt Camera Club in 1963 and bonded as probably the two youngest members there. He was working as a NZ Post Office linesman then, but clearly had an artistic sensibility. His wife Judy was a primary school teacher, then, I think, and after a while they introduced me to their friend Wendy Goldfinch, who had also trained at Teachers College. Consequently, Wendy and I married in 1964 and our children and Adele, Barry and Judy’s daughter, also spent a lot of enjoyable time together. Although I never got to meet Geoff Murphy or Bruno Lawrence among their artist friends, Barry introduced me to the jazz music of the greats such as Miles Davis etc. We enjoyed each other’s company and Barry and I sometimes went out photographing together.

Like mine, Barry’s photography was exploratory – trying to understand why the photographs we admired touched us at a deeper level than others. We wanted our photographs to stand out from the crowd during the process of finding ourselves, so we were all over the place in terms of choosing our subject matter and trying different ways of presenting our ideas. That can clearly be seen from the installation photographs I took of our joint exhibition at Artides Gallery, Wellington, in June 1965. The exhibition came about when Barry, who knew the Artides director, whose name I can’t recall right now, asked about us having a joint show at his ceramics gallery, and reflects the multiple influences and potential directions we could take with our own photography, from the prevalent old-fashioned neo-Pictorialism of the camera clubs to the latest and more challenging work seen in the major photography and mass media magazines from overseas.

Barry, I think, was more influenced and admiring of fashion and lively editorial photography, while I was, perhaps more interested in documentary values and the too-often ignored aspects of everyday life. Barry wanted to work as a photographer so it was not such a surprise when he became a professional commercial photographer in Wellington, making competent pictures for others. His “artistic” girly pictures, I thought, were run of the mill, and not art in my view. He had become, I thought, just another enthusiastic photographer unable to get above the demands of running a business. But to be fair, we had been out of touch since I moved to Auckland in 1971, so I have not seen much of his commercial work, nor personal work.

For me, our joint exhibition taught me two major lessons: that the value of making exhibitions involves seeing one’s intentions and outcomes in a cold hard light for the first time. And that this critical, self-revelatory experience is far more important than any private back patting or public praise.

--

Thanks to Matt Steindl and Sam Ardell at the National Library, Sal Criscillo, Colin Morris and John B Turner. The Simple Image exhibition ran at the National Library, Wellington, in mid-2021.