Jim Langabeer playing a pūtōrino. - Jim Langabeer Collection

Multi-instrumentalist Jim Langabeer, a mentor to countless musicians, was one of the artists featured in New Zealand Jazz Life (Victoria University Press, 2016) by Norman Meehan, with photographer Tony Whincup. This interview with Jim is a chapter from the book, republished with permission.

--

New Zealand Jazz Life by Norman Meehan and Tony Whincup (VUP, 2016)

Jim Langabeer is an essential part of New Zealand’s jazz furniture. My first contact with him was in the late 1980s when he ran MusAid, a local mail-order service offering instructional books and recordings. I had heard his album Africa/Aroha and been taken by the music which sounded up-to-the-minute and somehow different to what I had heard from other New Zealanders at that time. It was looser, more joyful, Jim’s saxophones and flute running like a bright thread through the weave of the ensemble. Jim wears a Garibaldi beard and the day Tony and I spent a few hours with him in his red music room he was wearing a pillbox hat. He has kind, mischievous eyes and is one of the most open people I have ever met. – Norman Meehan

Finding jazz

We used to import records. The government would only let you buy £4 a month worth of postal notes, and I used to collect five-shilling postal notes and send them to England. The LPs were always stopped by Customs, so you’d have to go to Customs and they’d ask, ‘What are these for?’ I’d say, ‘Well, I’m a musician and I want to listen to them.’ They’d ask, ‘Are you going to sell these?’ ‘No, they’re for my collection.’ Then, ‘Well, you’ve brought some of these in before: are you a licensed importer?’ On and on it would go. You’d go through this bloody thing every time – it was really strange. We talk about Russia, but we’ve actually been through all of that in New Zealand.

These measures were to protect local industry. Local industry was supposed to be producing these great jazz records. Some stores would get import licences, but even to get A Love Supreme or something like that was ridiculous: the average price of an album was 29s 6d, but to get A Love Supreme would probably cost 45s, 49s – twice the price because it was imported and there was extra duty on it, and there was no demand. So there would be one shop in Auckland and one shop in Wellington and one in Christchurch that would have a copy or two. They would excitedly ring you up: if it happened to be an Ornette Coleman or a John Coltrane LP, they’d ring me up and tell me; if it happened to be Louis Armstrong they’d ring somebody else up and tell them. It was incredibly hard to hear the music, but because it was hard, my friends and I would go through this same process of ordering records from England. Then maybe once a month you’d go around to someone’s place to hear their latest LP, and about three or four of these LPs would get played. In a sense it was quite good for the communal fraternising of musicians.

Whatever I got, I played it to death. I remember when I first heard A Love Supreme I thought, ‘Shit, that’s terrible.’ Then I listened to it again and I thought, ‘What’s he singing? “I love my dream”? What the hell’s he singing there?’ So I’d listen again, and, ‘Oh, he’s singing “a love supreme”.’ By the time you’ve heard it about 20 times and you’re starting to play along with it, by then you’re thinking, ‘This is fantastic!’ So in that way it was good. That’s how I picked up on Ornette Coleman, because I persevered with the records and tried to play with them. Somebody in the record shop recommended him. They said, ‘Everybody is raving about Ornette Coleman. A lot of people can’t stand it, but you might like it.’ So I got Ornette Coleman. I like a lot of the other players, but I like these kinds of guys – Coltrane, Ornette, Dexter Gordon – best. But they weren’t in New Zealand. They do beautiful, beautiful stuff, don’t they? And when they play fast, it’s good.

Jim Langabeer recording rock 'n' roll, 1955. - Jim Langabeer Collection

I loved playing music. My first real experience of jazz was when I was 12. I was playing trumpet and I’d already had several years on piano when I heard Louis Armstrong and Trummy Young, I think, on the National Programme, doing ‘Mack the Knife’. The trumpet solo – a quite bravura trumpet solo – was so different from anything I had heard, and it really excited me. And then the trombone solo came in and he played with a mute, so it sounded like he was playing an octave higher. I knew it wasn’t a trumpet but it didn’t sound like a deep instrument. And I really liked them both and I thought, ‘Gee, I wonder what that is?’ I started following up on it. I went into record shops and I’d say, ‘Have you got any music like this?’ and they would play some 78s. There was a lovely one by Charlie Parker playing ‘I’m in the Mood for Love’. Well, I could play ‘I’m in the Mood for Love’ on the piano, and when I heard Charlie Parker playing it – probably on one of those terrible Bird with Strings records – I thought it was gorgeous. So I learned that Bird solo on trumpet – it’s not difficult. Then, after a while, I thought, ‘Gee, the saxophone’s much nicer than the trumpet.’ I really liked saxophone, and I started to get a few more 78s; some Dizzy Gillespie, some Stan Getz. This was in the mid-1950s.

When I was 15, I worked through the Christmas holidays and made enough money to buy a tenor saxophone, then I spent the rest of the holidays teaching myself to play from a book called Teach Yourself the Tenor Saxophone. I started by learning some of the heads from a Dexter Gordon LP. I did it by ear; I never wrote them down. I knew how to improvise on the piano. I was friends with a guitarist and he’d shown me how to improvise – told me what chords and scales were and I kind of did that. You don’t need much information do you, really? I’m surprised that it can be a whole one-year 101 Learning to Improvise course. It’s pretty obvious: you can hear where the chords are changing; you can hear if you’re playing a major chord when on the record it’s a minor chord – it’s not all that hard.

Getting started

My parents encouraged my interest in music. My sister was a dancer and we used to make music at home. We’d get pots and pans and ukuleles and mouth organs and give concerts for Mum and Dad. Then Mum and Dad bought a piano at great expense and we started piano lessons. My sister stopped after six months and I kept going. I got up to doing a bit of Prokofiev and Mozart. I loved it but my heart wasn’t in it in the sense that I wanted to play – so I would much rather play guitar or slap bass with some guys my own age in a skiffle band – it was more fun than practising the piano, and that was when I shifted. That all happened when I was about 11 or 12.

I had a friend – Vic Williams – who played drums. He had very fast hands and he was a fantastic bongo player. He played drums and I was playing trumpet and a little bit of piano, and we got in another mate that I played tennis with, and he played guitar. The three of us formed a trio. We played everything, but we loved playing jazz and we improvised. We would play for social clubs, old folks’ picnics, talent quests. I used to go to a place called the Māori Community Centre, which was in Freemans Bay, right on Victoria Park. Every Sunday night they had talent quests there and we would go and enter. Sometimes we would do covers of the Everly Brothers or something like that, and sometimes we would do a funky blues – something that we’d heard by the MJQ or someone. Wherever there was a gap we’d jump in and do it. Mostly I went by bike: I used to put my trumpet on the handlebars and go to these places and probably turned up very sweaty.

Jim Langabeer (back right) with Freddie Keil and the Kavaliers. - Jim Langabeer Collection

The first real performing for money that I did was rock ’n’ roll in the late 50s or early 60s. I worked with a guy called Freddie Keil, playing piano. I used to do the Jerry Lee Lewis thing, standing up and plonking it out. We played teenage clubs and a lot of those sorts of things. I did that for a few years but I was still playing jazz, Ahmad Jamal and Dave Brubeck sort of jazz on piano. I was always playing the saxophone too, trying to get it down, although I was never very happy that it was any good.

In my second year at university I decided I would move from Auckland to Christchurch. I had met some Christchurch people and they seemed really interesting. So I went down to Christchurch and then I started playing at the jazz club there. Being in Christchurch didn’t go very well because I’d begun to spend more time writing poetry and writing short stories, and practising. Eventually I dropped out of my second year of university and just practised, five or six hours a day, with records on turntables.

I remember seeing an advert in the Christchurch Press, ‘Rock and Modern Dance Band Sax Player Wanted’, so over the course of a week I taught myself to play on the sax every tune that I knew on piano and went to the audition. They called things like ‘In the Mood’ and ‘Rock Around the Clock’, and I played it all and got the gig. I bought myself a new Selmer tenor sax and that’s when I became a professional saxophone player. This was about 1962.

Ted Meager, Jim Langabeer, and Paul Dyne, 1963. - Jim Langabeer Collection

The people at the jazz club in Christchurch seemed to like the milder Blue Note music, Stan Getz and sweet guitars and nice tenor saxophones. I was getting more and more into Coltrane and that sort of thing. I went to a couple of university arts festivals with a trio of tenor sax, bass, and drums, with Paul Dyne and Ted Meager. Somebody heard us and said, ‘You’re so good you should go on the radio.’ So we did a National Programme audition and got it, and we used to do a couple of programmes every year, for about five years. They were generally five tunes in half an hour. My scheme was, we would do two standards – say a ballad by Ellington, and a funky piece in straight-eighths of whatever was around and popular at the time – and three originals. So I would always write three originals for each programme and that was when I really started composing – because it got airplay and it was fun to do. I felt that was what they were doing overseas; when Coltrane and Ornette Coleman went in to make a recording they didn’t say, ‘Let’s do “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue” and a jazz version of “Rock Around the Clock”.’ They took in their own stuff. New Zealanders didn’t seem to be doing that. I can understand why – original music doesn’t necessarily have broad appeal – but it was good to do it.

Playing jazz, making a living

The music we played at the National Jazz Festival in Tauranga in ’67 and ’68 came out of the radio programmes I was doing with Paul and Ted, writing my own stuff. When I went to Tauranga I thought, ‘It’s a jazz festival. They want jazz.’ It’s not like playing at the RSA or the Working Men’s Club, where you slip in a bit of jazz, but basically they want to hear ‘Ten Guitars’ played by a trio – not the best way to play it. At Tauranga I did my usual thing of playing five numbers in a 30-minute set and I had three originals. At that stage I’d heard a little bit of Archie Shepp, I was listening to ’Trane, and I was trying to do my own thing. But I never tried to be way out, or ‘out there’. When people said, ‘This is the music of tomorrow,’ and everything – like hell it was; it was the music of today.

Superbrew - Africa/Aroha (Ode, 1984).

When you’re a trio you’ve got to play hard. When the sax player stops it’s either a drum solo or a bass solo, and they can only do that for so long. We were all young and after about two minutes of soloing we’d feel embarrassed, because that’s when our ideas ran out. So it was pretty much a matter of having quite a lot of interplay between the players and being as exciting as possible for a while, and then changing the mood and doing something else. That’s how my compositions tended to be. At Tauranga some liked it and some didn’t. I recently got a tape of the music – I had never heard it; it wasn’t released – and at the end of ‘For Eric, for John’ (my tribute to Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane, because both of them had just passed away) the applause is tremendous. I didn’t notice that at the time because I was taking the saxophone out of my mouth and thinking about the next number. So obviously some people liked it, but I’ve only just realised that. It feels good to know we played some jazz for a jazz festival audience who actually liked what we were doing.

Most of the time that wasn’t the case, and that is still true. Most of the time I’m playing other things. But that’s fine, I don’t only want to play jazz. I like playing other things as well. I try to keep my Mozart flute concertos up to scratch and I’m always interested in playing contemporary music; my groups explore lots of material.

I’m pretty sure that I was a left hander and I was changed to being a right hander. One of the weakest aspects of my academic side is my handwriting. It slopes the wrong way and I can only write so much before I need to take a break, write some more and take a break. I realised, after a while, that I play the way I write. I like to play in a short burst then have a little break, then play in a short burst and have a break. I don’t really like playing great big long phrases. Generally I only do that in a jam session when I decide, ‘Shit, I’ll double-time for a whole breath.’ And that’s really not good music, it’s just showing off. I don’t feel comfortable doing it; I’d much rather play haiku after haiku, rather than cadenza, cadenza, cadenza.

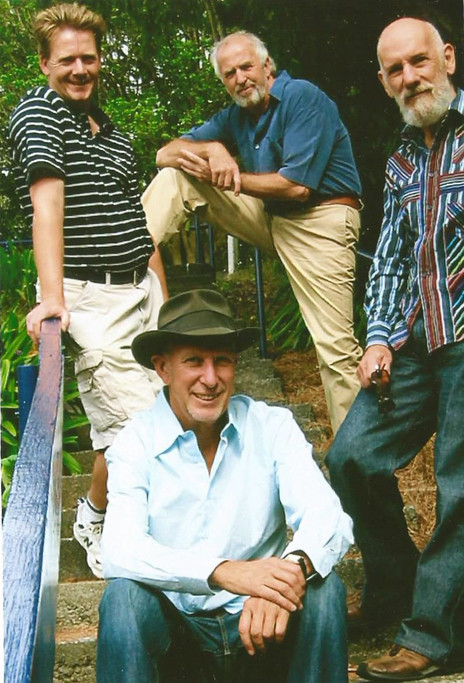

Jim Langabeer and friends. - Jim Langabeer Collection

Improvisation is the value in jazz that appeals to me. Coming back to Auckland I got involved with a group called Vitamin-S. I’m a maverick for Vitamin-S, because Vitamin-S is basically no discipline, no genre; it’s free improvisation. In Vitamin-S, for example, it would be an authentic performance to have a little hammer and to hit your saxophone and to make different sounds, perhaps putting that through a looped echo. So it’s not really jazz. When I play at Vitamin-S I take my flutes or saxophones and use them to create a range of different tone colours and sounds. But for me the most exciting thing is when we actually set up some sort of good rhythm – even if it is only in your head – and then we start playing around with it.

My parents were happy about me getting into jazz. I think I underestimated my parents in some ways. They were very conventional and hard-working. Yet in some ways they were quite free-thinking and encouraged my music, but not as a career. Dad went berko when I said I was going to leave during my first year at Auckland University because I’d been offered a job with a rock band and we were doing a tour. He said, ‘No, you’re not.’ So I agreed to finish my year at university. Dad said the same thing as my music teacher, Lew Campbell – a great trumpet player and arranger (I learned trumpet and little a bit of piano from him when I was 11 or 12). He said to me, ‘Jim, it is obvious that you’re quite an intelligent boy. I would recommend that you become a lawyer or a doctor and just keep music as a good hobby. It’s really a very tough profession in New Zealand, particularly if you love jazz.’ He also said, ‘And if you leave New Zealand because you think you’re really good – and you might be – and you get to England or America, you’ll start at the bottom again. And you’ll have to go through it all over again for five or ten years before you start getting gigs with good people. I don’t recommend it for a happy life.’

I don’t think jazz has ever made me any money. I’ve been on a few CDs, but mostly the best deal you get is, ‘Hey, we’d like to record your jazz group and we’ll give you the studio time for nothing, and you can have 20 CDs each for $10 each and you can sell those to your friends.’ That’s about as good as it gets. Most of the time, if you’re a sideman, they’ll give you two bottles of red wine and say, ‘Thanks – you played great.’

For money, I’ve been a teacher. Because I was interested in playing I started having people come to me and ask if I would teach them. I would usually say, ‘I really don’t have much that I can teach you, but come around and we’ll have a bit of a jam and we’ll go from there.’ I’d listen to them and say, ‘This could be better. If you practise this and do some of that, it’ll be better’ and you end up teaching them. I enjoyed that, and it set me in mind that I might like to be a music teacher, so I went to Teachers’ College and became a teacher. I was posted to Tauranga at one stage, and so I got into the jazz club there and put a lot of time into the Tauranga Jazz Society.

At the Auckland Jazz and Blues Club, 2006. From left: Chris Rowlands (bass), Ross Mullins, Trevor Thwaites (drums), and Jim Langabeer (saxes and flute). - Ross Mullins collection

I started up the high schools’ jazz competition in Tauranga, in 1977 or ’78, something like that. I really was trying to get jazz into schools – I thought it should be there. I had once applied to a classical summer camp to perform a tenor saxophone concerto. I did the audition, and they listened to what I played and said, ‘Well, we don’t have tenor saxophones.’ That was devastating because I was prepared to buy the music for this tenor saxophone concerto. I thought, ‘You’ve got the violins, I’ve got the tenor saxophone – why don’t we get together?’ But it didn’t quite work that way. It was the same in schools. I really pushed hard to have more jazz and popular music in schools and Tauranga seemed like a good place to have a schools component. It worked so well because it was a good idea at the right time, really.

I guess my heart is really more in small bands than big bands. What I mean is that a lot of big bands, stage bands and school jazz bands don’t play jazz. They play concert band music in a sort of Glenn Miller format with five saxes, five trumpets, five trombones, five rhythm, or whatever they can find. They play jazz charts, but they play like concert bands. The big jazz bands have much more improvisation, and their phrasing is different, and their dynamics are different and they have rhythm sections that can underplay and overplay and cook. Well, you miss all that when you codify it and teach it to a bunch of keen school children. A lot of the big jazz bands that you might hear around are more like studio ensembles of good players than a real jazz band. So my heart is in small groups. But I wouldn’t deny anyone the pleasure of playing in a reasonably boring, middle-of-the-road big band – that’s fine. It’s kind of like playing amateur tennis but never making it to Wimbledon: it’s still fun.

Jim Langabeer with Kingsley Melhuish (trumpet) and Harold Anderson (bass). - Jim Langabeer Collection

Getting Real Books in New Zealand was much like getting records. [Real Books are anthologies of lead sheets – abbreviated scores – of songs commonly played by jazz musicians.] You couldn’t buy Real Books in New Zealand, and yet every person who had been to Berklee or Boston would come back with a Real Book. I spoke to some of the guys associated with jazz educators Jamey Aebersold and David Baker about this. They suggested I get in touch with a guy in Australia and bring some Real Books into New Zealand. I did that but he soon dried up. I went to New York and met the guys who were producing the Real Book, but they dried up too. It was one of those things where you got chased out of town every now and then. Then I decided that the Real Book could be more useful if it had a reasonable selection of different types of tunes in it. So I put out a version that had some ballads, some blues, some standards, and I tried to make it a nice balance of stuff that people could use as a teaching tool as well as a useful gigging tool. It was quite fun.

Chuck Sher, the publisher, got onto me about that. Somebody told Sher that I was handling Real Books and that I shouldn’t be. I got a legal letter, so I stopped doing it.

Overseas

Finding your own sound, and building your own sound, is very important. I didn’t feel I was able to do that in New Zealand, so I went away. When I was playing in New York, one of the guys in a little group I was playing with – an American – said, ‘You’ve got a different sound.’ I said, ‘I’m from New Zealand,’ and he said, ‘Yeah man, you play different. I like it.’ I was used to people in New Zealand saying to me, ‘You play different, and it’s awful.’ In New Zealand I felt that people didn’t like what I played and that they didn’t like my sound, and that was very hurtful. Personally, I read it as, ‘I better go away and do more practice.’ So for that guy to say that, it was a big thing.

I did learn a lot overseas. I didn’t particularly like the Los Angeles and San Francisco clubs – they were good but they weren’t much different from Australia and New Zealand – but the first time I went to a New York jazz club and heard some good tenor players I learned a lot. I learned that they were pushing out the sound the way I felt it should be pushed out. Not bombastic, not over the top, but full and resonant. It sounded so gorgeous. So I worked on trying to develop that.

The first time I went away was for about six weeks. It was really concentrated. I was mostly in New York. I was offered a gig in Germany by some German musicians, and I was very tempted to go, but there were a few things that were up in the air and I also had a family back in New Zealand and I thought, ‘No, I’m not going to be the runaway jazz player.’ I learned a lot, mostly by listening, but I did have the chance to be with some really great players and workshop some things with them. David Liebman was the saxophone player I mainly worked with.

Later I played a few concerts with Gary Peacock. I met Gary because we were both interested in Zen Buddhism. He’s a Zen Buddhist, I’m a Zen Buddhist, although that doesn’t really mean much because Zen Buddhism is one of those all-encompassing mindsets. But the thing that we both shared was the idea that you put all of your attention into what you’re doing while you do it. So when you’re working with Gary you have to be really listening to everything he’s doing, and you know that he’s listening to everything you’re doing. It’s very good in terms of free jazz because you are supporting each other and building with each other. One of things that can happen in jazz groups is people stop listening and only hear what they are doing themselves. I think it is essential for the music that you have bigger ears than that.

The state of jazz

I think jazz in New Zealand is healthy and there’s a lot of it. But where does it fit? I feel that jazz is a genre like chamber music. Chamber music is played by a small number of people for an audience that really likes to come and listen to it. I think the jazz I like is kind of the equivalent of that, only it’s 20th- or 21st-century music. But there are only a handful of clubs where that kind of jazz happens and it is almost impossible to get a residency in those clubs. The best you can hope for is that you might get two or three gigs a year playing in a jazz club. That’s hardly going to mature your style or mature your music. I don’t really know how you do that in New Zealand.

It says something about the popularity of jazz that there are so many good musicians – hundreds – who are prepared to give their lives to it. It is certainly popular with musicians, but I don’t think it gets wide exposure. Every now and then there’ll be a series of six concerts, which means six bands get to play, and maybe a year later it’ll happen again. But it’s not enough, is it?

Jim Langabeer and Trevor Reekie, Trip to the Moon, 2012. - Jim Langabeer Collection

About a year ago a pianist friend of mine invited me to play with him in a club in Parnell, and every second week I would go there and I would play quiet but exciting jazz on flute and tenor saxophone and clarinet. We really kept it under control and we played in this club from about six until nine at night. About the third time I played there, there was a table that erupted. There was great applause, and they said, ‘Fantastic. Could you play “Round Midnight”? Could you play “Take Five”?’ And I said, ‘Sure,’ and we did. And about a week later there was a blog and it said, ‘The best jazz in New Zealand can be heard at this club in Parnell.’ There was all of this extravagant stuff in there that made us blush. We were so pleased. A week later the manager said to the pianist, because he was the leader, ‘You’ve got to get rid of that sax player, because I wanted background music. I don’t want jazz.’ So I got the sack. I don’t know how to navigate it. I wasn’t playing Coltrane or Ornette Coleman. If anything I was playing Paul Desmond and Stan Getz, on clarinet and flute. I was playing quietly and the audience was loving it, and I got the sack. So I don’t know how to promote jazz or what to do about it. Wynton Marsalis comes to town and he plays in the town halls and he sells out. How do we do that for local jazz musicians? We play in clubs and they ask for a gold coin collection ...

A New Zealand jazz

I think there could be a New Zealand jazz, and it’s a shame there isn’t yet. I think that there have been a few groups – Colin Hemmingsen and Phil Broadhurst with Sustenance, perhaps – who have been composing and playing and starting to sound a little different from the American, British and Australian groups.

I feel that the jazz departments in the universities almost have a duty to encourage that experimentation with New Zealand sounds and New Zealand themes. It’s not as easy as it seems – easy to say, but difficult to do – but I don’t feel that has happened in the jazz schools. The schools have largely just copied what’s already been going on, particularly in the States. But European jazz doesn’t necessarily sound like jazz from the United States and I don’t think that New Zealand music should sound like the music that comes out of the academic side of the United States. We learn by copying, but then we may sing in our own dialect, use our own rhythms and create our own expressive styles. If a New Zealand sound is going to develop, it is almost going to have to happen in isolation in New Zealand – and I don’t think we hasten that process by using copycat curricula from overseas universities. I do think there’s got to be a bit more done within the universities to accomplish that New Zealand sound.

I would like to think it will come from smallish groups and that some mixed media would be involved. With SuperBrew we did some performances where we had eight musicians and eight dancers, and I wrote some original music for that. The times we did it, it was quite spectacular and got a great response, but no one came along and said, ‘Why don’t you tour it, or put it into an arts festival?’

I’m interested in what my daughter Rosie’s doing: I think she’s interested in this sort of mixed-media stuff. I gave my daughter Rosie the same advice my teacher had given to me – don’t try and make a career of it. And fortunately she didn’t follow my advice. She’s doing quite well, and musically it’s great.

Jim Langabeer died in January 2022.

Jim Langabeer and daughter Rosie at Michael Parekōwhai's red Steinway. - Jim Langabeer Collection

--

Jim Langabeer profile and list of works at Sounz.

Jim Langabeer at Discogs.

A tribute to Jim Langabeer at JazzLocal32.com

A review of Norman Meehan's New Zealand Jazz Life.