Gallipoli and music seem an unlikely combination, yet – as with every other location during the First World War – melody managed to slither through the misery. It helped to remind the soldiers why they were fighting, or perhaps to forget.

Moments after the troops’ arrival on 25 April 1915, musicians were among the first casualties. Between ship and shore, a bullet hit a singer of comic songs remembered as just “Skinner” of the Auckland Regiment. The stretcher bearers of the Wellington Battalion and Taranaki Company made it ashore quickly. “The beach was utter chaos,” recalled bandsman/stretcher bearer Laurie Smith. “No one seemed to know where anybody else was.”

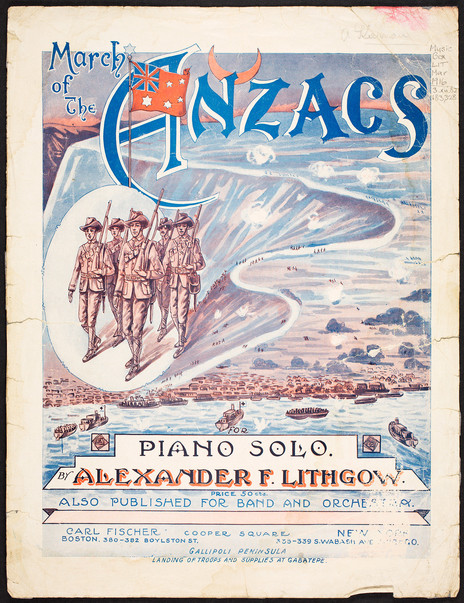

‘March of the Anzacs’ by Alexander Lithgow, composer of ‘Invercargill March’, 1916. The sheet music cover depicted “the landing of troops and supplies at Kabateple [Gallipoli]”. - National Library of New Zealand.

Their first duty was to one of their own: Frank Shirley, a former Taranaki bugler, was felled by a bullet. “He popped his head up for a look, and got clouted good and hard,” said Smith. His friends had to lie on their backs to avoid the Turkish snipers, as they pushed Shirley over a low cliff to be caught by other stretcher bearers and then attended to by the battalion doctor, Captain George Home.

Just two days after landing at Anzac Cove, 20-year-old bugler George Bissett from Taranaki was killed at Monash Gully during a day of fierce fighting. After a week, Bissett’s body was spotted by his commander Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone; he was lying face downwards, and on his back was a bugle, punctured by bullet holes. After a month, a 24-hour armistice was agreed so that both sides could bury the dead on No Man’s Land, no matter what their nationality. Malone wrote in his diary of the “poor shattered humanity”, decomposing after so many days exposed to the air. “As dreadful a sight I suppose as could be.” Among those buried was “the Bugler lad Bissett”:

I am glad. . . . It is a desecration of the human body to leave it shot up, and unburied for long. . . . At 4.23 [p.m.] the armistice ended, and the firing recommenced. I had a good look at the Turkish soldiers they look good, and well fed and clothed, and seemed cherry [sic] and friendly enough. At 7 p.m. Hawkes Bay Coy gave a concert, but the rifle firing became so furious and noisy that it was impossible to hear, so we sang God Save the King and went to bed, at about 7.30 p.m.

George Bissett's bugle, punctured by bullet holes at Gallipoli, 27 April 1915. - National Army Museum Te Mata Toa, Waiouru

Major Peter Buck described the difficulties of day-to-day life on Gallipoli. The place itself seemed to “rise steeply from the seashore. We were hanging on by our eyebrows to trenches dug on the near margins of the slopes.” At least the trenches were safer than the beach, but conditions were taxing. The men tried to cook on their own canteens, using twigs and branches from any nearby shrubs as firewood, but mostly these were just for making tea. Water was brought up from the beach in sealed cans, and rationed to one gallon per man. Wiping their faces with a damp cloth was the closest the men got to a wash. Food was out of tins, and when opened a swarm of flies would suddenly arrive from their “usual abode”, a nearby long-drop. Yet singing at Gallipoli was not unknown. A month after the landings, Colonel William Malone wrote to his wife:

We get some music here, all vocal. Last night one of my companies gave a concert. ‘Mary of Argyle’, ‘Sweet and Low,’ and ‘The Veterans Song’ (Long Live the King – don’t you hear them shouting – is the one I mean) were very well sung, but after about 6 songs, we had to bunk off. The machine gun and rifle fire, with an odd shell burst, made such a row that we couldn’t hear.

Immediately after landing on 25 April, the stretcher bearers filled gaps in the line until they could join their battalion. At Walker Ridge, they tirelessly administered first aid, carried the casualties down a steep ridge to the beach, then laboured back up with supplies; several were wounded. Observing them was Malone, who recommended that six be mentioned in despatches. Malone requested the stretcher bearers to assemble near a first-aid post, and suggested they sit down and have a smoke while he said a few words. The bandsmen had begun to respect Malone’s wisdom, despite their confrontations with him back in New Zealand. But they were surprised when he said:

Men, I have seen the work you have done since the landing and I want to thank you personally for it. I also want you to know that when I used to ride behind you in New Zealand and in Egypt, the thought often used to cross my mind that you seemed to be a cold-footed lot sheltering behind brass instruments, and I want to apologise to you for this. I hope that you will forgive me for, like you, I had never been to a war before and knew not what you would be called upon to do. I am sure that the battalion is proud of you, and when I write home to the papers I shall make mention of your work.

Malone had changed his tune about the musicians soon after the landing. Following a night of torrid fighting, in which he estimated nearly three million rifle bullets had been shot at them by the Turks, Malone wrote: “Everybody has done well. Even our – in peace-time – much-abused bandsmen, as stretcher bearers have done great things working night and day, walking, climbing, carrying wounded, mostly under fire.”

Otago Gully Headquarters Staff, Gallipoli, November 1915. - Photo by Lawrence Doubleday (Te Papa, CA000316/002/0017)

Despite being almost absent from the official record, band music was heard by the New Zealand troops at Gallipoli. Enough bandsmen were sent to form four bands. However, the casualties among the musicians quickly mounted. By August 1915, when success at Gallipoli was looking doubtful, it was decided to form battalion bands, principally to revitalise the men’s morale. But the losses were appalling; the Wellington Battalion alone, 700 strong, was reduced to just 48 officers and men. The most that could be managed was to organise 30 soldiers into a brigade band. Laurie Smith, a bandsman/stretcher bearer, recalled an occasion at Argyl Dere on Gallipoli, when a band played “within 100 yards of the Turkish lines ... the small band ensconced itself below a ledge jutting into a valley that sloped up to the Turkish lines. There, with bullets whistling past, the men played imperturbably as if their only aim was to fill the valley with sound.”

To forestall battle fatigue, the Canterbury Battalion organised several concerts in the Canterbury Rest Gully. The Turkish trenches were nearby, so the first concert was held in the dark. The bandmaster said before they started that “any man hit during an item must not disturb it by any outcry”. The Turks did not cooperate however, and the Canterbury band’s debut concert was accompanied by the rattle of a machine gun. The next night, the Turks brought their own band into their trenches, “but memories of the previous evening’s entertainment were spoilt, the melody being badly punctuated by a bomb accompaniment. The effects of these concerts, however, proved a miraculous tonic to the spirits of the men.”

An Australian officer recalled New Zealand troops holding a concert at Gallipoli a few months after the 25 April landing: “One man with a cornet proved a good performer; several others sang, while some gave recitations. We all sat round in various places in the gully, and joined in the choruses. It was all very enjoyable while it lasted; but, as darkness came on, rifle-fire began on the tops of the surrounding hills – also, occasionally, shell fire. This completely drowned the sound of the performers’ voices, and the concert had to be brought to a close.”

Some evenings, the Anzac troops could hear talking or music coming from the Turkish trenches. It might be a gramophone, an unaccompanied singer, or a soldier playing the harmonica. The tunes included some significant to the Allies: the ‘Marseillaise’ or ‘Tipperary’. But it was rare for Anzac troops at Gallipoli to have the energy or opportunity for music or concerts. Reading, smoking and gambling – using a “wealth of cigarettes” – were the only diversions Rikihana Carkeek enjoyed in his dugout christened Tangi-o-te-mata Residence (the call of the bullets).

Unlike France, there were no small cafés, no canteens, no towns or civilians. There was little respite from the trenches, apart from the occasional swim in the Aegean risking shellfire. Even their rations were grim: hard biscuits, or bully beef that was vile at the best of times, but which turned to liquid in the summer heat. As historian Max Arthur points out, it is unsurprising that one of the few songs to emerge from the Gallipoli trenches concentrated on food. Although many songs were written about Gallipoli after the event, ‘Oh, Old Gallipoli’s a Wonderful Place’ is a rarity: a trench song created on the peninsular by Anzac troops. Like so many of the soldiers’ songs, it was a parody written to another song’s melody, in this case ‘Mountains of Mourne’: “Oh, old Gallipoli’s a wonderful place / Where the boys in the trenches the foe have to face, / But they never grumble, they smile through it all, / Very soon they expect Achi Baba to fall.”

One of the few Zealand soldiers who, when enlisting, nominated their occupation as “musician” was Auckland-born composer Arthur Vivian Carbines. Before the war he had written hymns, songs and instrumental pieces and became a well-known musician in Auckland and New Plymouth as a singer, organist, pianist and cellist for institutions such as the Baptist Church and Orphans Clubs. In 1907, when he returned from two years’ study in London, the New Zealand Observer described Carbines as “one of the most promising musicians in Auckland ... equally at home on any instrument from a tooth comb to a pipe organ”.

Carbines volunteered two weeks after war was declared and soon wrote ‘Toast to Maoriland’, using his own lyrics to the melody of ‘There is a Happy Land’. It naively looks forward to active service, while lamenting the culinary travails at his training camp: “German sausage isn’t it / When at fighting we begin it, / On a tin-in-in of Bully Beef”. On 8 August 1915, during an assault on Chunuk Bair, Carbines was clambering back into a trench after recovering wounded men when an inexperienced British officer mistook him for a Turk and fatally shot him.

On the troopship to Gallipoli in 1915, Lance-Corporal Alexander Aitken carried a violin smuggled in his kitbag. He later became a world-renowned mathematician. - Edinburgh University Library

While music on Gallipoli was uncommon, a discreet exception was the violin played by Alexander Craig Aitken, a Dunedin-born student who became an internationally renowned mathematician. Aitken, a lance-corporal with the Otago Infantry Battalion, left Lemnos for Gallipoli on 9 November 1915. Smuggled in his kit was a violin he had been given on his troopship to Egypt; he hid the instrument during kit inspections, and it was occasionally passed from hand to hand among his fellow soldiers to remain out of sight. Leaving Lemnos, the battalion band played for the departing soldiers as they marched towards their ship, then turned around and returned to base. Aitken pondered the musicians’ status: “For the moment I thought it odd that the ability to play a brass instrument should exempt a man from coming on with us to Gallipoli; but the Army was the Army and had inured us to shrug off any anomaly like that.”

Aitken’s immersion into the reality of Gallipoli was swift. He left his violin in the care of a friendly Australian, “a hard-bitten old hand”, then climbed towards Chunuk Bair. Soon, he comes across a stretcher party carrying a Wellington Battalion soldier, ‘shot through the head and dying”. He recognises him as a friend: “A glance was enough to show that he would be dead in a few minutes.’ In the 7-foot trenches facing Chunuk Bair, Aitken and his Company were 220 yards away from the Turks; between them were “rusty wire entanglements”. They took their duties in shifts: eight hours on, eight off. Fifteen yards behind them was another trench, in which they slept, using the blankets of those on duty as well as their own.

In the bitter cold between midnight and dawn, they were indispensable. We slept in our uniforms, rifle at hand-reach, and, until the December weather made it unavoidable, did not remove boots or socks, and often slept in full equipment in case of surprise. I need not describe vermin; . . . the greater part of modern war, when of the static type, consists precisely of such monotony, such discomfort, such casual death. And so let it be stripped of glamour and seen for what it is.

Aitken quickly became jaded about the war, his leaders, their tactics, the waste – and the euphemisms to justify it all.

We take refuge in vagueness, or in noble phrases like the “sombre aftermath of victory”, or in traditional emollients, dulce et decorum est, or sed miles, sed pro patria, or something found in such a non-combatant poet as Tennyson. From that time on, and lastingly, such usages would rouse in me an impatient protest. Let these things be called by their proper names, and war will be extirpated the sooner.

A blizzard in November accelerated plans for the evacuation of Allied troops from Gallipoli. While preparing a cave for a possible rearguard action, Aitken retrieved his violin from the empty dugout of its Australian minder. He would occasionally play it in the evening.

Each night we had a muted concert in the largest dug-out. My E-string had gone, but a resourceful Aucklander unravelled the strands of a short length of the six-ply field telephone wire, and these substitutes served until I bought proper strings in Cairo next April. There was no room for the sweep of the bow-arm, while the Humoresque, or anything like it, was out of key with Gallipoli; but Christmas was near, and carols with muted obbligati were softly intoned. In its time The First Nowell will have been sung in strange places; this dug-out under Chunuk Bair must have been one of the strangest. After the last of these subdued concerts I stooped under the waterproof door-sheet and stood for a minute waiting for the diffused light to show me the way to my slot-bed. The contrast was extreme; inside, the warmth and comradeship of men far from home but remembering it and forgetting the war for a brief hour ...

Gwyllymn (Lew) Jones was another musician with a violin concealed in his pack when he landed at Gallipoli in late September 1915; aged 20, he was a gunner with the New Zealand Field Artillery. Jones and his fellow soldiers soon came under heavy fire. All around him men were being wounded by Turkish fire, and he was quickly surrounded by “dead, dying and wounded comrades”. According to family lore, Jones picked up his violin to comfort the men. “It seemed for at least a moment that the war was silent.” However, Jones and his violin were hit by gunfire and he lay wounded in the hills of Gallipoli until he was rescued, leaving his destroyed instrument behind.

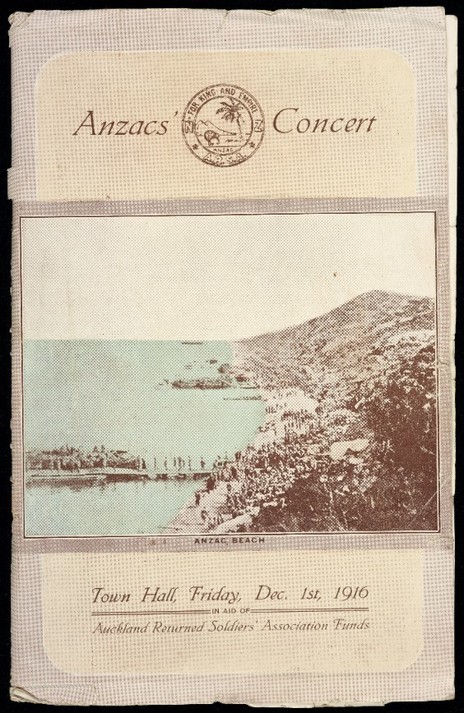

Programme for an Anzac memorial concert, Auckland, December 1916. The cover photograph shows the landing at Anzac Cove. - Eph-A-Variety-1916-01-front, Alexander Turnbull Library

The lingering nightmare of Gallipoli came to a sudden if silent end when the British high command decided to evacuate the Allied troops from Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay. Eight months after the chaotic invasion, the troops’ departure was well planned and executed. Over several days before Christmas 1915, under the cover of night or decoys, equipment and supplies were removed or destroyed, and troops carefully made their way down the valleys to the beaches to be transferred to the waiting troopships.

On 13 December, Alexander Aitken and his men received instructions to report at the beachhead. “We cleared up and reported on time. The violin had to be left; I scribbled a hasty note to Chadwick, batman to Major W. W. Alderman, asking him to look after it if he could.” To Aitken the instrument was as good as lost, but a few days later on Lemnos, Chadwick came looking for him. When packing Alderman’s kit at Gallipoli, the officer had said, “Shove it in with my stuff. Some fellows get attached to these things.” The violin was one of the last personal items to be removed from Anzac.

Aitken describes the various decoys used during the evacuation to trick the Turks into thinking the fight was continuing: rifles set up with devices to make them fire automatically; parties of men with bathing towels heading to the beach, as if for a swim, then returning fully clothed. The Regimental Band “had, indeed, come from Lemnos and played in a secluded gully”. By 20 December the evacuations from Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay were complete: the men were safely on board and the ships were heading to Egypt. In the eight months of the Gallipoli campaign, of the 17,000 New Zealand soldiers who landed, about 7500 were casualties, including 2779 dead.

On the departing troopships, “Restraint was thrown aside”, wrote Fred Waite. “New Zealanders from the Apex and the Lone Pine rear-guard of Australians danced wild measures with the sailors on the iron decks ... So we said good-bye to Anzac. Next morning the Turk rubbed his eyes and proclaimed a great victory.”

--

An edited excerpt from Good-Bye Maoriland: the Songs and Sounds of New Zealand's Great War, by Chris Bourke (Auckland University Press, 2017).

Sources:

Alexander Aitken, Gallipoli to the Somme, OUP, London, 1963; Alex Calder (ed.), AUP, Auckland, 2018.

O. E. Burton, The Auckland Regiment, Whitcombe & Tombs, Auckland, 1922.

John Crawford (ed.) with Peter Cooke, No Better Death: The Great War Diaries and Letters of William G. Malone, Reed, Auckland, 2005.

John Crawford (ed.), The Devil’s Own War: The First World War Diary of Brigadier-General Herbert Hart, Exisle, Auckland, 2008.

‘Hippo’, ‘The Colonel and His Band’, part 3, New Zealand Mouthpiece, June 1965.

Fred Waite, The New Zealanders at Gallipoli, Whitcombe & Tombs, Christchurch, 1919.

Audio and Video links:

Great War Stories 3: Alexander Aitken

Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story: full-length documentary written by Maurice Shadbolt, 1984

Bugle Stories 5: George Bissett and his bugle

NZ On Screen: First World War collection

Farewell Zealandia: RNZ’s 2015 recordings of songs written by New Zealanders during the First Wold War