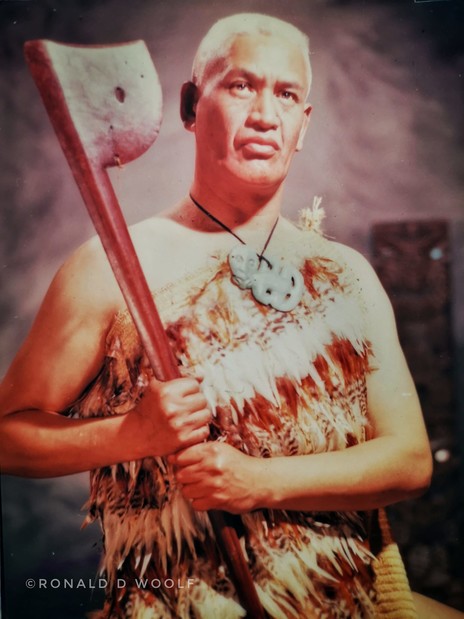

Wiremu (Bill) Kerekere was well-known in the worlds of songwriting and music. He came across as a dignified, gentle, self-effacing person, a measured speaker with perfect elocution and intonation, and a stylish and elegant dresser. He was a descendant of chiefly lines among his people. He was also a wise man who walked in two worlds, a musical genius, a powerhouse organiser, a superb teacher, and a man of the people.

The following is a rendition in English of AudioCulture’s Wiremu (Bill) Kerekere profile, which was conceived and written in te reo Māori.

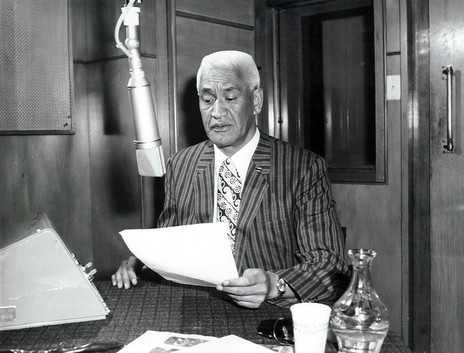

Wiremu (Bill) Kerekere recording a radio script, 1966 - Archives NZ, R24804408

Bill was a caring mentor and guide to me as a young radio colleague when I went to work at Radio New Zealand in the early 1980s. I had begun to learn te reo as a young adult, and I knew Bill only as an announcer who read the Māori language radio news on 2YA, he became a constant as a language speaker and role model. He had a commitment, very Māori, to utter every word with clarity and accuracy. He also knew and understood the power of the voice and intonation. Each word seemed to chime with meaning, and music.

Bill was born in Gisborne on 8 August 1923. He was the son of Kohikohi Karauria Kerekere of Te Aitanga a Mahaki, and Tahua Kingi, of Mataatua, Te Arawa, Tainui, and Waikato and Te Aitanga a Mahaki. He was born in a shearing shed, where his mother Tahua was working. After the baby was born, fed and tended she went straight back to work at the wool classing table. He was educated at Waerenga a-hika College and Gisborne Boys’ High School.

According to Bill, his career as a composer began when the college kapa haka ran out of songs he began to put Māori lyrics to existing melodies.

In my recording work among native speakers of Māori across the southern North Island and South Island I found a practice adopted by many, if not most, whānau Māori with traditional leadership roles after 1900. Many expressly forbade their young men and women from speaking and learning Māori, and sent them to boarding schools where they were not only educated in the sciences and classics, but also expected to adopt English manners.

The family holds the story that when Bill’s mother died he was away at boarding school at Waerenga ā-hika College. His father decided not to tell Bill that she had died, so as not to disrupt his education. The British born headmaster had the practice of lining up the boys to salute a funeral cortege as it passed. On this day Bill lined up with the others and gave the salute, not knowing it was his mother in the hearse moving up the road.

The soldier and the WAAF: Wiremu (Bill) and Mihi Kerekere. "He was stationed at Trentham and she was stationed at Wigram," says their oldest daughter, Raana Tangira. "They met somehow, somewhere." - Kerekere whānau collection

In April 1945, Bill married Te Haumihiata Sarah (Mihi) Parata of Ngāi Tahu, and the couple had five children.

Like most young Māori men of his age, the Second World War drew him in, and he enlisted in the C Company (the East Coast North Island section) of the Māori Battalion. They set sail as the last reinforcements to North Africa and Italy but hostilities were over by the time they arrived. His section was diverted to Japan as the war ended there, and joined the New Zealand J Force, before returning home.

Bill Kerekere “created the limelight for others to stand in,” said Bub (Ngapo) Wehi

Bub (Ngapo) Wehi, later on leader of Waihīrere kapa haka, had moved from Ōpōtiki to Waihīrere in 1951. In an article published shortly after Bill’s death, Wehi described the ethos of Waihīrere village at the time of Bill’s youth: “[There were] households where Mum and Dad, koroua and kuia, were all singers. They used to have their hit parades. Everybody would gather round the wireless and they’d catch all the tunes, just like that. Then they’d put Māori lyrics and actions to that Pākehā tune and you had a ready-made action song. You’d have a new tune too, to razzle-dazzle the hosts, next time your pā went visiting. In those days that was important. The mana of a hapū depended on its ability to entertain.” (After Bill passed away, Bub said of him, “He created the limelight for others to stand in.”)

Bill was naturally musical and mastered the piano. As well, with an insightful teacher urging him on, by the age of 13 he had convinced the local private radio station in Gisborne to give him a fortnightly show playing the piano and singing. The signs for his track in life were already clear.

This kind of music was deeply ingrained in family life. In an interview with Henare Te Ua now archived at Ngā Taonga, Bill recalled: “My father played, my sister played, my mother played, we all played an instrument, just for the fun of it, we weren’t taught music as such, we just enjoyed getting together and singing and the whole marae had the same concept. At the marae, the piano was the centre of all musical evenings.”

Bill Kerekere with US harmonica virtuoso Larry Adler, at Darton Field airport, Gisborne. - Gisborne Photo News, September 1961

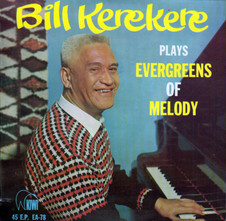

When the famous harmonica player Larry Adler visited the East Cape while touring New Zealand in 1961, Bill accompanied him on the piano. This moment was included on the LP featuring Waihīrere Māori Club, A Treasury of Māori Music (Kiwi). Later, Bill recorded his own EP, Bill Kerekere Plays Evergreens of Melody (Kiwi, 1963). It was reviewed in Te Ao Hou by Alan Armstrong, a well-known non-Māori writer, brother-in-law to Henare Te Ua and also an ex-army man, who became an indefatigable writer of books on Māori culture. Armstrong gave Bill’s performance on the new record featuring his piano-playing a scintillating review:

“Now Kiwi have featured Kerekere in his own right, and he thus becomes the first popular Māori pianist on record. He plays in the modern style but mercifully does not belong to the school which are so carried away by their own virtuosity that one can only guess at the original tune amidst the jumble of ‘variations’. Although Mr Kerekere improvises with zest and ingenuity – he is an able exponent of the rippling arpeggio and the counter melody against his own accompaniment – yet he is careful not to overplay his hand. The melody comes through strong and clear, but with plenty of light and shade. The result is a sparkling little record which is playable over and over again.”

Bill Kerekere Plays Evergreens of Melody – this 1963 EP on Kiwi featured six standards. "The record has proved a good seller," wrote the Gisborne Photo News, "and could well lead to bigger things for Gisborne's 'reluctant genius' ... the term used to describe Bill by visiting musician, Larry Adler."

Bill grew up in the era when Apirana Ngata and Tuini Ngāwai were alive and composing, and Māori song composition and performance on the East Coast was a major cultural force, as it remains today. To broadcaster Henare Te Ua he recalled being tutored in composition by Te Kani Hetekia Te Ua, father of Henare, in Māori musical performance, both traditional and modern, and kapa haka.

By the 1950s Bill had become the major leader and driver of the Waihīrere kapa haka group, still going today, a proverbially famous and admired group in te ao Māori.

Raana Tangira, Bill and Mihi’s oldest daughter, reports that the Waīhirere Māori Club was formed in the 1950s by her Uncle Te Kani Te Ua, Uncle Panapa Tuhoe, Aunty Ani Tahuka and her father. “They were all cousins. When the club was formalised, Leo Fowler [manager of 2XG Gisborne] was the Club Secretary. He was dearly loved by the Waihīrere people – and was buried in the urupā [cemetery] in the vicinity of the marae.”

Waihīrere was relied on for kapa haka entertainment on major occasions throughout the Gisborne district. For an iwi visit to Waikato, Bill composed an action song of greeting, ‘Karanga mai Korokī’. The occasion was a coronation annual hui in 1963, during the reign of King Korokī. Despite the nervousness of younger members of the group, according to Bill, Te Kani Te Ua reminded them of their tribal obligations, and assured them they could perform well, and carry out their task.

He also enjoyed the dance band music of the day, and played this kind of music for 20 years. He was the pianist in the Ray Zame orchestra, prominent in Gisborne.

The Ray Zame Orchestra, from left: Ray Zame, Bill Firth, Harry Ratcliffe, Theo Cameron, Herbie Clare, Bill Kerekere, and Sandy Hovell. The band – prominent in Gisborne in the 1950s and 1960s – reunited to help raise money for the Rotary Club to buy a piano as a gift to the city. - Gisborne Photo News, November 1975

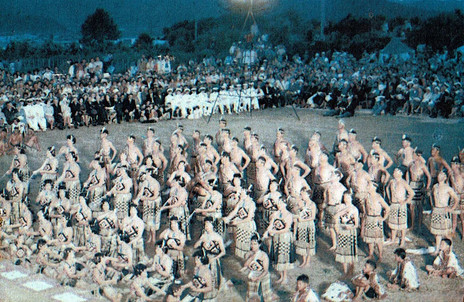

High-level perfomance at ceremonial occasions became an abiding interest for Wiremu. This led to associations with other iwi and musical leaders, and his role in organising performances for royal visits from 1963 on. Bill’s compositions were admired and learnt throughout the country. He composed ‘Karangatia e Te Iwi’ for Queen Elizabeth II in that year; it was performed at two later pōhiri for her, in 1970 and 1977.

The Waihīrere Māori Club, rehearsing at Waitangi for its performance before Queen Elizabeth II, 1963. - Kerekere whānau collection

He later described its origins to Henare Te Ua. In 1963, Queen Elizabeth II was to be welcomed at Waitangi in the far north of New Zealand. The senior leadership of Te Tai Tokerau, including Hone Heke Rankin, felt that the North did not have the quality of haka and waiata performance expected for the occasion at that time. They made a request to Waihīrere of the Gisborne area to come and perform. Bill explained that the request was turned down twice with a response that the northern iwi by right had the role of performing. But they came back a third time. And at that point Te Kani Te Ua said, yes, Waihīrere will come to Waitangi and perform the pōhiri. Bill also explained that for Waitangi, the idea of a waiata with an existing Western tune was dismissed, and the request was made for Bill to compose original items.

Bill’s family reports that when the idea of a Polynesian Festival was being discussed he took part in meetings with Māori Affairs Minister Duncan McIntyre, Sir Kingi Ihaka, Jock McEwen and others. A significant feature of Bill’s life in subsequent decades was his role in participating in and supporting the Aotearoa Traditional Māori Performing Arts Festival, which now runs every two years. It later became Te Matatini, the national senior kapa haka festival.

Bill worked in the Department of Māori Affairs in Gisborne for several years until, in late 1964, Leo Fowler asked him to move to Wellington to help set up the Māori programmes department of the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation (NZBC) in Wellington.

WIremu (Bill) Kerekere preparing a radio programme, 1966 - Archives NZ, R24460988

After considerable thought and consultation with his wife, elders and peers, Bill accepted the appointment and the whānau moved to Wellington in January 1965. With Fowler’s years of experience and expertise in broadcasting and Bill’s matauranga Māori and connections to Māoridom, they made a great team. Over the years, Bill became a respected Māori language radio broadcaster and a national figure.

Reconnecting with Ngāti Pōneke Young Māori Club in Wellington was inevitable; when he and Mihi were in their respective Forces, he had courted her – with chaperone of course – at the Ngāti Pōneke dances and events. Going back there at this stage of his life he was able to “give back” to Ngāti Pōneke by helping with kapa haka and composing items. ‘Tangihia’ was one of those.

The Waihīrere Māori Club during its performance in front of Queen Elizabeth II, Waitangi, 1963 - Kerekere whānau collection

Bill coordinated a number of mass pōhiri including several royal visits, among them the royal family to Waitangi in 1963, the visit of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip to the Polynesian Festival in Gisborne in 1977, the opening of the 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane in 1982, and the visit of the Prince and Princess of Wales (Charles and Diana) to Gisborne in 1983.

Wiremu (Bill) Kerekere - a portrait by Ronald D Woolf. - © Woolf Photography

He also took Ngāti Pōneke to record at EMI studios in Lower Hutt in 1973. The album Aku Mahi featured four songs written by Bill (‘Ka Huri Au! (I Turn To Greet You)’, ‘Tu Maramara Noa Te Tu Poneke!’, ‘Ko Taku Whakapapa!’, ‘He Aha Taku Maoritanga?’); he also arranged ‘Karangatia Ra Pohiritia Ra!’.

Senior EMI producer Alan Galbraith recalls Bill as a superbly organised leader, and a very likeable person. “The sessions were always well-organised and rehearsed, so not much for the rest of us to do.”

Bill has nearly 50 of his compositions registered with APRA. Among his best-known are ‘Kei a koe’, ‘Ko taku Whakapapa’, ‘Papaki nui’, ‘Tangihia’, ‘Te Paki O Matariki (more commonly known as ‘Maru’), ‘Tū Maramara Noa’ and ‘Tūmaramara Noa te Tū Pōneke’. In 1976 he wrote recorded ‘Aotearoa’ – a reo interpretation of ‘You’re Our Way Naturally New Zealand’. Both songs were released on a Philips (NZ) single, with Desna Sisarich singing the English version on one side, and Bill singing ‘Aotearoa’ on the other.

Wiremu (Bill) Kerekere received an Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his work in Māori cultural performing arts in 1972. In October 1995, he received a citation from the Music Advisory Committee of the Lilburn Trust, part of the Alexander Turnbull Library Endowment Trust, “in recognition of his outstanding contributions to Māori Music and to Broadcasting”.

He died in Gisborne on 10 June 2001 and was buried at Waihīrere. His whanau say “There’ll always be a note missing.”

--

Audio: Hēnare te Ua interviews Wiremu Kerekere, 1984 (Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision)

Audio: Hēnare te Ua interviews Wiremu Kerekere, continued

AudioCulture’s Gisborne Tairāwhiti Story Map

AudioCulture’s Māori Music Collection