‘I Just Wanna Be Like Marlon Brando’ was not a hit or even close to one, and nor would it have been much remembered if it wasn’t for the fact that the singer would, two decades later, be hailed as one of the greatest actors of his generation, with skills at times compared to Brando by critics.

in his years as a pop-wannabe in New Zealand, it was clear CROWE was somewhat driven.

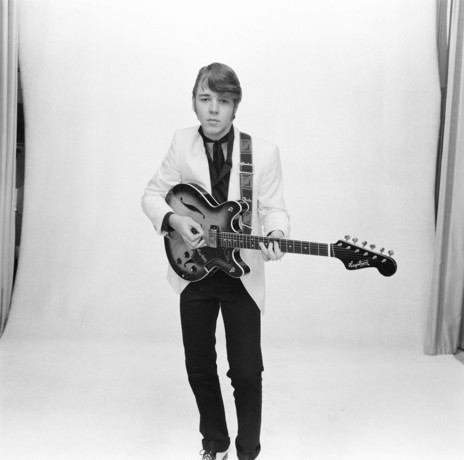

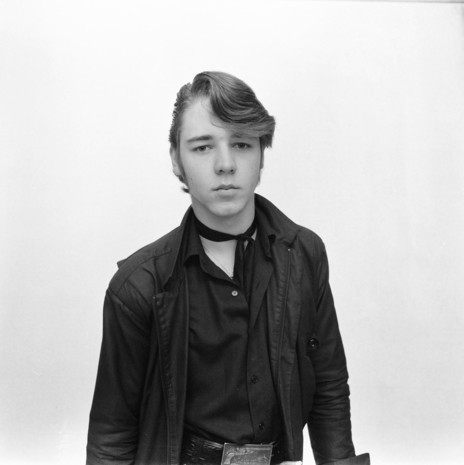

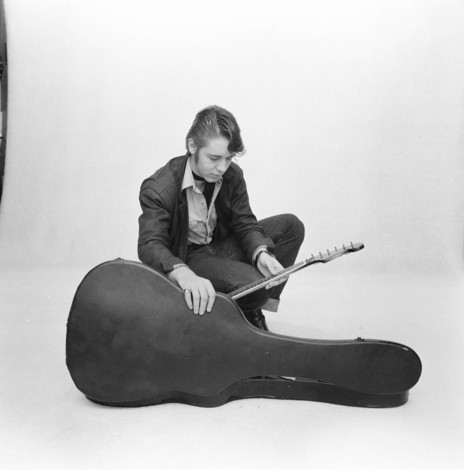

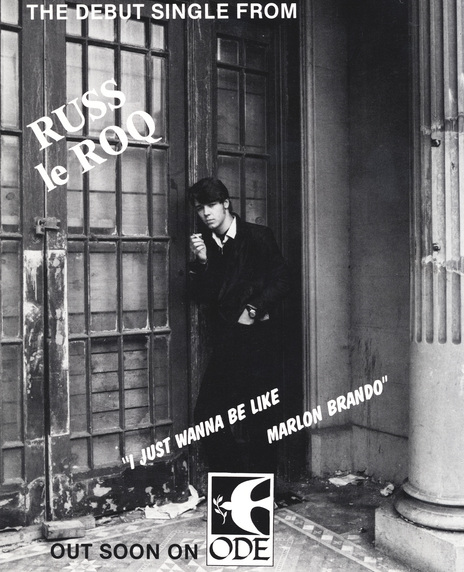

It wasn’t even a particularly good record, in fact, it was rather awful, but to everyone who knew Crowe in his years as a pop-wannabe in New Zealand, it was clear that the singer was somewhat driven. Indeed, the sleeve of that single has a very moody Crowe leaning in a doorway, ciggie in hand, looking confident beyond his then rather lowly position in the Auckland pop strata.

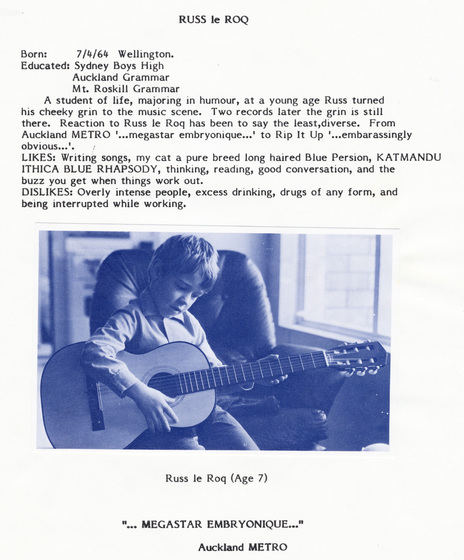

It shows some determination, and a 1983 Russ le Roq press release includes “being interrupted while working” as a pet hate, along with “excess drinking” (one has to be amused at yet another irony here – Crowe’s extreme partying over the years has long been notorious) and “drugs of any kind”. However, it’s a strange, almost detached determination rather devoid of anything beyond the pose. He stands, he stares, he shows complete self-belief. But you just know that the record is going to be merely passable, which rather precisely set the parameters of Russell Crowe’s career as a musician going forward into the 21st Century.

It seems everyone who was going to gigs, playing in bands or simply there in those somewhat in-scene post-punk days, has a Russell Crowe story to tell. Perhaps that’s because he refused to play the conformity game. He always seemed out of step with fashion, and either oblivious to that or more likely he’d calculated that conformists are usually overlooked. And, yes, it was hard to overlook the confident and aspiring singer who could often be found near the intersection of Queen and Wellesley Streets in a jacket that said simply “RUSS” on the back.

the confident and aspiring singer dressed in a jacket that simply SAID “RUSS” on the back.

I spent some time with Russ around the door of A Certain Bar, the Peter Urlich and Mark Phillips-run dance club in Albert Street where I'd be corralled into filling in from time to time when door-bitch Tina had the night off. Now and then a bunch of us would hang out afterwards at King Creoles, the rock and roll club across the road in the Civic building, owned by Russell’s musical mentor Tom Sharplin, where Russell was the resident DJ, playing records in a DJ booth set in half a Cadillac hung from the ceiling, a booth that Auckland DJ Andy Vann, who also played there, described as “rather unstable.”

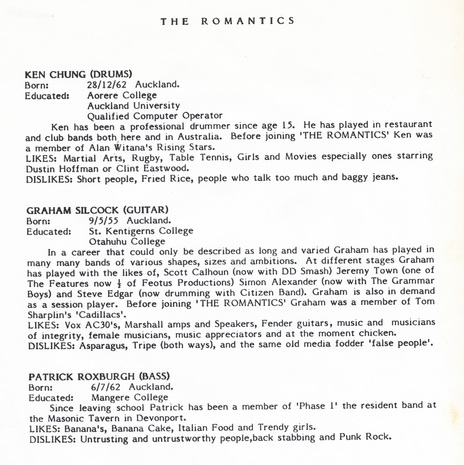

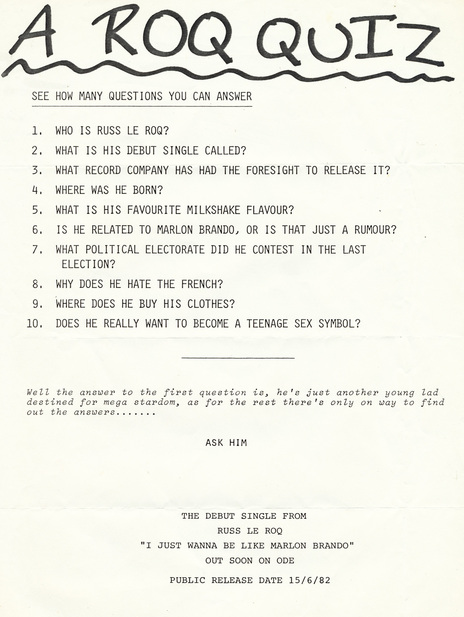

Crowe first spotted Tom Sharplin at age 14 when the popular rock and roll revivalist played at his father’s pub in New Lynn. Crowe latched onto Sharplin, with the older rocker seemingly happy to oblige with direction and advice. It was the beginning of a life-long friendship that still survives. It was Sharplin who coined the name Russ le Roq for the kid, and supposedly suggested the title of the ‘Marlon Brando’ 45, although I doubt there was much resistance to the latter. The song was then recorded with the Tom Sharplin band backing Russ, in a small studio in Pakuranga, Auckland.

I liked Russell, and I wasn’t the only one – Ode’s Terence O’Neill-Joyce told Philip Matthews at the NZ Listener in March 2001, “He had an innocence about him ... he was just a nice person.”

However, it was clearly a driven innocence, uncontained by the parameters of the then accepted “cool”, which was very much New Romantic and post-punk.

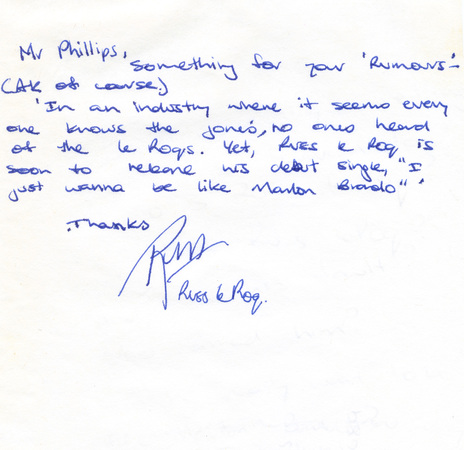

A handwritten note to Rip It Up in 1982 said, “In an industry where everyone’s heard of the Joneses, nobody has heard of the le Roqs.”

But he certainly tried – I still have my autographed copy of ‘Marlon Brando’, signed just after release by the cocky kid. He told me it was great but I doubt I played it more than once.

The last time I saw Russ le Roq, although he’d long since dropped the name of course and was a little embarrassed by it, was around 1996 in Auckland’s High Street. I was walking past Rossini’s café when I heard my name called. Looking, I saw Russell gesturing to come in. I did, we had drinks, Peter Urlich joined us and Russell invited us both up to his father’s pub in Whangaparoa for the evening, offering to pay taxis back. I declined but I think Peter accepted. Russell had already Romper-Stomper-ed by then and was on his way to becoming Marlon Brando, having signed up for the movie LA Confidential, but was still more or less the same guy you can see in that doorway cover shot. I suspect he still is, except he now knows he was right, and those classmates that laughed at his aspirations can go …

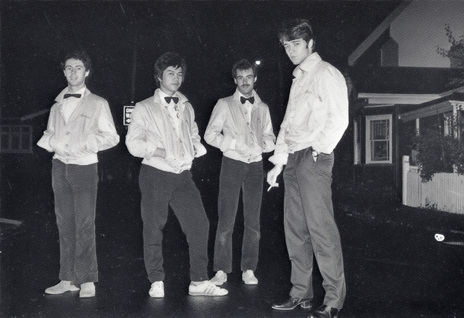

It’s a somewhat geographically twisted tale from his 1964 birth in Wellington, but one well covered elsewhere. Suffice to say that by early 1982, having formed his first band, Profile, at Mt. Roskill Grammar a couple of years earlier, the kid from the conservative bible-belt ‘burbs had thoroughly reinvented himself as Russ le Roq and was telling anyone who would listen that he was going to be a star. The Crowe name was barely heard anymore and Rip It Up’s Russell Brown told Philip Matthews that he never knew, until years later, that the singer was a Crowe (as in a cousin of Martin and Jeff, the cricketers).

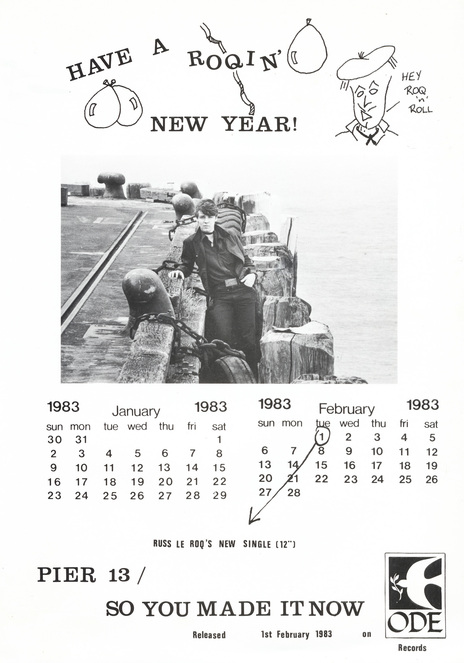

A second single ‘Pier 13’ is now listed as a “limited edition of 100”.

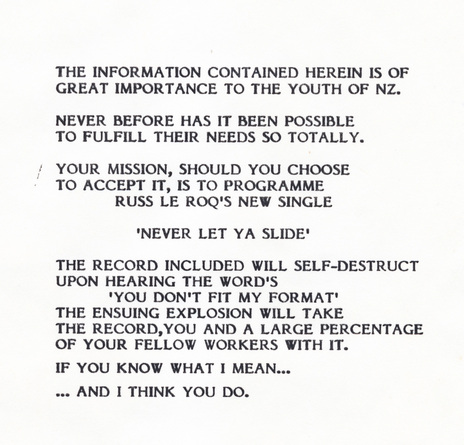

A second single ‘Pier 13’, in early 1983, was a bigger flop than the first and has now been reinvented in the mythology as a “limited edition of 100”. Nobody who wants to be a star limits a single to 100 sales.

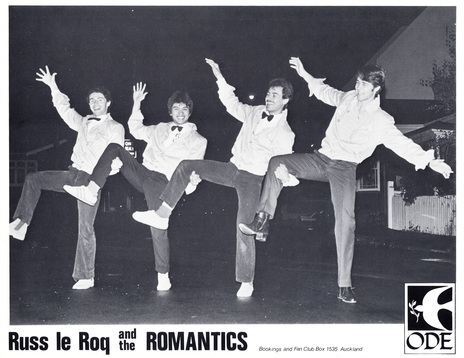

By now he had a band too, Russ le Roq and The Romantics, and it was under the name that single number three ‘Never Let Ya Slide’ was released in mid-1983, to similar sales. Moving to CBS, and produced by Trevor Reekie, single number four ‘Shattered Glass’, a lightweight synth-pop record – perhaps the only record he’s made which played to contemporary styles – again was a no seller and CBS decided not to release a follow-up.

Reekie offered a frank assessment of ‘Broken Glass’, explaining to Philip Matthews, “We tried to jazz this piece of shit up and it didn’t work at all! But he was a laugh.”

Crowe’s next move was a nightclub. The Venue, in upper Symonds Street (No. 134, previously the State Theatre), opened in February 1984. Unlicensed to allow the kids in, it was briefly quite hot as a place to play, with a steady stream of the hip, synth-heavy pop acts that were dominating the Auckland inner-city scene, and the hottest DJ in Auckland, a young guy from Whakatane, Roger Perry. Russ, naturally, found a regular place for himself and his band on the stage.

"I'm really proud of The Venue … it was a place where kids could go to hear live music and it wasn't licensed. Kids tend to think of live music being a special event rather than the inherent part of their lives it should be," Crowe told the NZ Woman’s Weekly in 1989.

But it wasn’t to be. Despite the initial fleeting hipness of The Venue, crowd numbers quickly dropped, and with those left unable to buy a drink, it wasn’t financially viable, struggling by mid-year, before closing messily in November.

Reekie again: “It was an under-age club and it was the wrong part of town.”

Philip Matthews blames street kids, driven from Aotea Square by the police, and he’s probably correct as Crowe said to Rip It Up at the time, "It would be easy to become a racist running the venue, which would be odd as I'm part Māori myself". Appropriately perhaps, it was converted to a roller disco before being demolished. A strip of faceless shops now fills the space.

A compilation of new bands, All Dressed Up And No Place To Play was released in November 1984, made up of tracks from eleven bands chosen by Russell from those playing at The Venue. All tracks were produced by Russell at Bill Lattimer's Lab Studio, taking advantage of a $100 per day recording offer from the studio.

Russell told Rip It Up's Russell Brown, "There was a lot of energy in some of the sessions." Sadly that energy was not translated in sales or careers as almost every band on the record seems to have disappeared without trace thereafter.

Russ also found time to be a band manager, guiding The Bellboys, whose lineup included future Mockers and Bads member Brett Adams.

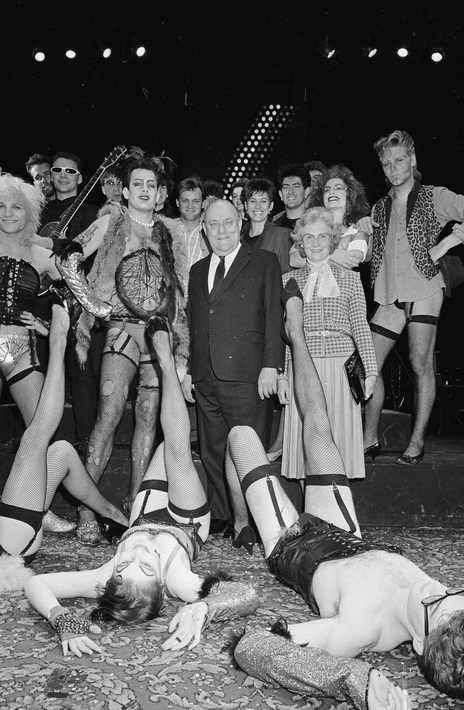

Then, following a five-month tour of New Zealand in 1986 as part of The Rocky Horror Show, Crowe headed across the Tasman to his glittering future in early 1987 (he would rework that date to “early 1980s” in future press releases). Russell Crowe would tell the NZ Woman’s Weekly that he was “doing demos for EMI” in 1989. If they were completed, nothing came of them.

1985 SAW RUSS LE ROQ GIGGING WITH HIS NEW BAND ROMAN ANTIX.

As The Venue closed, a still determined Russell Crowe said to Rip It Up “I still want to be a pop star”, and so 1985 saw him as an entertainment manager at Pakatoa Island in the Hauraki Gulf, and gigging with his new band Roman Antix, effectively a duo with guitarist Dean Cochrane.

They released a final Crowe New Zealand single, the rockier ‘What's The Difference’, self-produced but recorded by ace engineer Jon Cooper, so sounding tougher than earlier releases. It reviewed reasonably well – probably the only record of Russell Crowe’s musical career to receive positive notices, but it too sold almost nothing. It was as out of step with the times as his earlier releases.

Roman Antix’s Dean Cochrane would turn up again in Crowe’s third to last band, the ungainly (both in name and stylistically) 30 Odd Feet Of Grunt, who, despite a festival doco and all Crowe’s substantial PR muscle, largely disappeared, although the second album, Bastard Life Or Clarity, debuted at No.7 in Australia. Crowe then – in 2005 – formed The Ordinary Fear Of God, which issued an album called My Hand My Heart that same year and then contributed a solitary track to a 2010 Australian collection of songs by singer John Williamson.

2011 saw the digital release of The Crowe/Doyle Songbook Vol. III, a collaboration between Russell and Alan Doyle, featuring Danielle Spencer as a guest vocalist on most tracks.

A new band, Indoor Garden Party (Crowe, Doyle, Samantha Barks, Scott Grimes, and Carl Falk), released the album The Musical in 2017 and it briefly hit No.1 on both the iTunes and Amazon charts.

Crowe told AudioCulture in 2018 that he considers The Musical to be "the first time I’ve properly finished a record.

"Indoor Garden Party is a hell of a band. I continue to be deaf to critics & remain grateful for the privilege to lead a deeply creative life."

Russell's musical career continues and may well provide him with the sort of musical recognition he wants and given Crowe’s 35-plus years of music creation, only a brave person would suggest it won’t, especially when considering the unabashed and critically slammed Crowe vocal performances in the 2012 movie version of Les Misérables. They somehow brought to mind the words of Mark Rimmington, who performed with Crowe in the 1986 Rocky Horror Show. Rimmington told Philip Matthews in 2001, “I had to shadow sing him when we were doing the tour, to keep him in tune. He never said he was a great singer, he said he was a great frontman. He knew how to do a show.”

He did, and he certainly does.

--

Read more: Russell Crowe’s rock’n’roll hunger – 1981 photo sessions

Read more: Russell Brown on underage club The Venue (Rip It Up, November 1984)

--

Sources:

Philip Matthews, NZ Listener, 24 March 2001

Garth Cartwright, NZ Listener, 3 May 2003