Australia’s musician, lawyer and politician Peter Garrett joined New Zealand’s political artists Jools and Lynda Topp in a nationwide “Nuclear Disarmament” tour. Wellington journalist Michèle A’Court managed to catch up with them for a couple of days for student paper Salient.

March, 1985 – Ten o’clock on a Monday morning and the Massey campus is a mess. Hundreds of hot, sticky students push their way through the Student Union building, trying to go somewhere. Upstairs in a small office, the Topps and Peter Garrett are recovering from Auckland, Tauranga and Hamilton, and preparing for Palmerston North, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin.

So far, the tour’s been good, especially on campuses. Maybe there should have been more people at the public show in Auckland, but in Hamilton the audience was great. “Quite remarkable for Hamilton,” Jools says.

The tour was organised by Peace Movement Aotearoa in conjunction with the New Zealand Students’ Arts Council. Local members of PMA handled some of the publicity for the tour and organised places to stay and transport for Garrett and the Topps.

Associate Director of NZSAC, Margi Mellsop, travelled with them as tour manager, dealing with the inevitable crises that make tours so exciting.

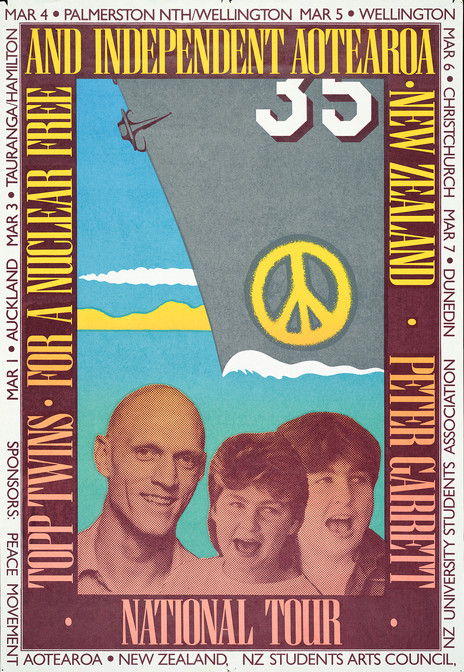

A poster from the Topp Twins' 1985 tour with Peter Garrett, in support of "a nuclear free and independent Aotearoa" - NZSAC/NZUSA; Eph-E-NUCLEAR-1985-02, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

At least one of these happened in Palmerston North. Half an hour to show time it was discovered that the planned venue for Garrett’s talk and the Topps music was off limits. It was supposed to happen in the caff but the university administration – which owns the union building – wouldn’t allow the chairs and tables to be moved to let all the students in.

Sound systems are hastily moved to the concourse outside and Garrett grabs a rubbish bin to use as a lectern.

Long before the tour got to Palmerston North, Garrett had thrown away the speech he wrote in Australia.

“My message has changed. I thought my message would have been one of articulating my own feelings about nuclearism, how I got to this point and what we needed to do – because in Australia, that’s what I spend most of my time doing now.

“Now that I’m here I’ve thrown away that speech and I’m really just encouraging New Zealanders, giving them a sense of support and hope, and recognising the remarkable, historical significance of their action.

“It’s an honour to come and speak in a country which has taken the first step to creating some sort of nuclear-free future. It has the potential to affect the rest of the world in a way I don’t think most New Zealanders yet realise.”

Garrett says the effect of our ban on nuclear-capable warships has been quite remarkable in Australia.

“People in the streets, taxi drivers, in the pubs – they’re very, very in favour of Mr Lange, and they’ve got respect for New Zealand.

“I think we’ve seen with Mr Lange a leader who, at least in the early stages, may not have been strongly committed in his own politics to the anti-nuclear movement. And yet now he is a most effective and proper advocate of the New Zealand position.

“I would expect Mr Hawke to do the same thing … if in fact the Labour Party adopted that policy.”

He’s aware of the anti-Australia feeling here resulting from the pressure Bob Hawke tried to put on the New Zealand government. Someone told him about the sheep-dip commercial.

“We [the NDP] demanded that Mr Hawke acknowledge the right of New Zealanders to take their chosen action. I think you’ll find the more the United States threatens New Zealand, the greater the support you’ll get from Australia.

“Don’t be misled by the media image and the cricket and all this nonsense … We know that New Zealanders are our mates. We might have a closer relationship with the United States than you do, but you’re our ally, our close neighbour.”

If any of that sounds overly polite and effusive, it’s not meant to. What impresses about Garrett even more than his appearance is his genuine enthusiasm for what we have done as a nation. Incongruous as it may seem, Garrett shows an almost childlike excitement when he talks about peace and disarmament, and it is this that audiences have warmed to throughout the country.

The Topps: “We don’t talk, we sing speeches”

The Topps fill the first half of each show with their songs. (“We don’t talk, we sing speeches.”)

Says Jools, “The songs that we’re singing in this tour – the anti-nuclear songs – we wrote those songs two years ago. They’re having more effect now.”

Linda elaborates. Audiences are picking up more on the politics in the Topps’ songs because of the context of the tour, and because the nuclear issue is the No.1 issue in New Zealand right now. And that’s because the Prime Minister has stood up and said “No” to nuclear ships.

Jools: “And he’s backing up this tour beautifully, really, isn’t he …”

The Topps agree that the whole tour has become a “political art thing”.

“If you want to sing something about a really strong issue you have to feel it in your gut before it comes out any good as a song,” says Jools. “Everything you experience in your life is political … It’s just being aware of what is around you, what’s happening to you.”

After the music, Garrett speaks. Later in the day, to an audience at the Wellington City Art Gallery, he talks about the relationship between art and politics: “When the music isn’t enough, we become politicians.” He has stepped off the stage and into the political arena for a moment because there are things he wants to say that he couldn’t express through Midnight Oil.

“Music is a good way of reflecting political movement, political change, political emotion. Music can mirror the time and a political feeling but I don’t think it’s a good way of articulating a political argument,” he says.

“I’ve left my art behind for a moment to do non-violent battle against the people who threaten my creative art.”

Not left behind entirely, though. Garrett’s speaking style is not so far removed from his stage performance style. He still dances, he still uses his hands and body to mime his message, and he still entrances his audiences.

Following the lunchtime show at Massey there are radio interviews on campus and in the city, then on the road to Wellington. It’s raining in Levin when we stop for Chinese takeaways and it keeps on raining all the way to the capital.

At Paraparaumu, we’re stopped on the bridge by a car bearing the sign, Wide Load Follows. The bloke in the car sees Garrett driving and winds down his window. Garrett does the same.

The bloke is in his 40s and couldn’t look less like a Midnight Oil fan or a peace freak but you can tell he knows who he has just stopped on the Paraparaumu bridge. His “How’s it going mate?” is tentative, but Garrett’s warm response makes him happy.

They have one of those “men’s talk” conversations about nothing in particular, then he glances at the other passengers and says something like, “You all together?” We all nod. “Look a pretty healthy bunch.” He smiles, waves and is gone, chasing the wide load which is half way to Waikanae by now. Wait till he tells them at home.

This travelling between cities is an important time for Garrett and the Topps. Away from telephones and people asking questions they get a chance to talk about the last show, to talk about their interviews and to give each other support. The Topps tell Garrett about New Zealand politics, about bumping into David Lange in a Mangere supermarket, about Māori land struggles. We talk about Tahitian independence leader Charlie Chin being arrested only three days earlier for trying to hold a rally against French nuclear testing in Tahiti.

Jools and Linda are like “political minders” for Garrett and he absorbs their information. The three share the same belief that “nuclearism” has links with other forms of oppression and they reinforce each other’s views by swapping stories of their own experiences.

“Our job is to broaden people’s ideas of the nuclear issue because there are other things that link into it,” Linda says. “Some people are so overwhelmed by the nuclear issue they can’t think of anything else.

“We know the other issues are linked in because they affect us. A lot of people don’t see it, but when it happens to you … when you’re hit by sexism and racism in the anti-nuke movement, you think ‘Fuck it’.”

Jools: We accepted this tour with Peter Garrett because we think it’s important that women have a say on a tour like this. Sometimes we think Peter doesn’t go far enough. It’s got to do with the indigenous people, it’s got to do with the women’s movement, it’s the whole thing.

“Our message on this tour is that, okay, we’re fighting a bomb – the bomb – but we’re fighting the system that makes the bomb too, because the same system that makes the bomb allows apartheid in South Africa, it allows the oppression of women.

“If we all join together and say, ‘Wow, let’s get rid of the bomb’ and it happens, where do the black people and the women stand? What have they got to look forward to? We cannot have a nuclear disarmament throughout the whole world and women still being raped.

“It doesn’t stop at the end of the bomb. We’ve got to learn all the way through.”

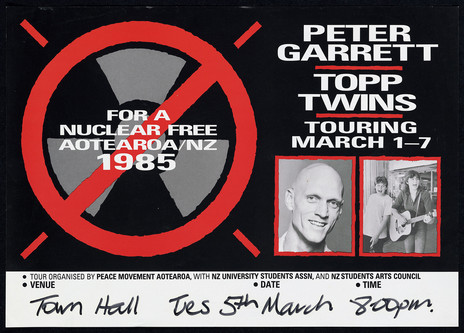

The Topp Twins tour New Zealand with Peter Garrett, in support of a nuclear-free Aotearoa. The March 1985 tour was organised by Peace Movement Aotearoa, with the NZ University Students Association and the NZ Students Arts Council. - NZSAC/NZUSA; Eph-C-NUCLEAR-Roach-1985-01, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Garrett, too, talks about fighting the system that makes the bomb. In an interview with the Australian National Times last October he described the birth of the NDP as “a signpost for people disillusioned with the political system who want to vent their view about this particular issue … Being anti-nuclear means you have to change the system, change the way people think.”

Garrett explains now that when he talks about “the system” he is referring to both “capitalism and socialist imperialism” (the Soviet Union, for example).

“In my view, the only advantage that the system we live under gives us is the freedom to express ourselves and the freedom – if that way inclined – to achieve material gain. The other system doesn’t allow us that freedom and it’s to be deplored for that reason.

“By the same token, the system that we are now living under has provided us with the means of destroying ourselves … and if we don’t kill ourselves by letting off bombs with one another we may well kill ourselves by chopping down trees and poisoning the ecology.”

In both systems, Garrett says, we can see an implication of oppression in the use of power. “We have even built weapons which have taken the idea of power as far as it can go …

“… And we thus see power for what it actually is: the power to destroy.”

But how does Garrett want to change the system? He believes we need to reassess the kind of systems we want to develop. He’s talking about political evolution, not revolution.

“I think they can be developed out of the systems we have now, very easily. You can see it quite clearly in the political developments in Europe with the ‘greens’ parties … I hope the Nuclear Disarmament Party is heading things in that direction – not necessarily for it to become a ‘greens’ party, but for us to start going in that direction.”

It’s still raining when we park outside the Wellington City Art Gallery. Garrett has been asked to talk about art and politics, and the Topps are ready to perform with him. But it turns out that the Topps are not expected to play.

As two of New Zealand’s best exponents of political art, they’re disappointed about being left out of this part of the tour. But they don’t make a big deal about it. The Topps are tired and could do with a rest, and anyway, to jump up and down about it and say, “You’ll let him talk but won’t let us sing” would put Garrett in a difficult position.

Maybe people felt that it was okay to talk about political performance, but not to actually do it.

Maybe people felt that it was okay to talk about political performance, but not to actually do it.

One version of the reason behind the Topps not being invited to perform is that there was some objection to the Gallery being used as a venue for a show about nuclear disarmament. The story goes that the objection came from members of the Wellington City Council, which runs the Gallery on behalf of the people of Wellington.

Anne Philbin of the City Art Gallery denies that this happened. The invitation had only been extended to Garrett, she says, and there was never any intention that The Topps would perform.

During his talk at the Gallery, Garrett makes the point: “Art has a very great power to communicate. It must be used as strongly as we can. We don’t have many resources available to us apart from our art.”

As the Topps stand at the back of the audience during the evening’s discussion, Garrett’s point hits home. The Topps have a valuable contribution to make to any discussion on art and politics and the only way they’re going to communicate it is through their art.

At the time, we believed that local body politics had stolen this opportunity from them. Even if this isn’t so, we should remember that though New Zealand stands out as a world leader in the anti-nuke struggle, we still have some work to do at home.

The day isn’t over yet. Late on Monday night, Garrett goes on nationwide talkback. Garrett’s energy level always seems to stay high, as if talking about nuclear disarmament somehow gives him the energy to go on talking.

What Radio New Zealand doesn’t tell him (or anyone else involved in the tour) is that Bob Jones is going to be brought on line for the talkback as well. Garrett doesn’t get a chance to be briefed about the New Zealand Party or its leader.

Some people would have walked out of the studio. Garrett stays and battles it out for a chance to be heard on air.

It happens again the next day in Christchurch. This time, pro-nuke campaigner, Dr Jim Sprott is brought on the line from Auckland. To be fair, Radio New Zealand were in some doubt about whether Garrett was going to be available that night. But again, nobody tells Garrett that’s he’s sharing the talkback – this time with a complete adversary.

At the Town Hall, Linda and Jools get a standing ovation.

Tuesday, and it stops raining in Wellington. Garrett and the Topps do their stuff for Press Gallery reporters, politicians, and Victoria University students. In the evening they’re welcomed in Māori to the Town Hall. Linda and Jools get a standing ovation. Garrett is received warmly as a new friend.

Garrett talks about the sacrifices New Zealanders may have to make in maintaining the nuclear ban. He believes that while some trade sacrifices will have to be made, they won’t be enduring sacrifices.

“I believe there’s a very strong argument to be put for exporting nuclear free products … it’s not a silly idea, it’s a really practical, sensible thing to do. It may not make up for the trade embargoes in a two or three month period, but in a year or two it will more than make up for that.

“I think New Zealand’s greatest export will be peace. Peaceful goods, the healthy and good things that you grow here.” Visions of nuclear-free kiwifruit, no-nukes butter.

“Van Camp chocolates and Steinlager are already a politically sound gift to give – as all New Zealand things will be. For any company that won’t import New Zealand products, you’ll find plenty of companies that will.”

On stage and off stage, the Topps are getting us to focus on the next step.

Jools: “It seems odd that a New Zealand government that has said, ‘We will not allow nuclear ships into our waters’ – it’s like saying we don’t want to kill anybody, we want to be a peaceful nation, we haven’t got any enemies – will then turn around and allow a rugby team to go to South Africa.

“That totally undermines what we’re doing on the nuclear issue. That’s something else people will have to deal with.

“Rugby isn’t everything. People have thought that for a long time. But now, politically, we are becoming really aware. And that’s nice.”

Peter Garrett: “My own perspective on nuclearism is slightly different from a lot of other people’s. I’m lucky, I get to travel, I get to go to other places, motels, hotels, televisions, different countries, and I can see this big movement. I know it’s happening. I’m part of it myself – just a part of it – and New Zealand’s part of it but, like it’s a national part of it. And that’s very, very significant.”

--

First published in Salient in March 1985, this article appears with the permission of the author.