The last time the Verlaines played in Auckland, it was, as I recall, a rip-roaring affair. The dancefloor was a sweaty jumble, on the stage the three musicians were propulsively intense, more so when a guest guitarist got up for ‘Lying In State’. The quiet little encore of ‘Don’t Send Me Away’ only emphasised the fury of what had gone before.

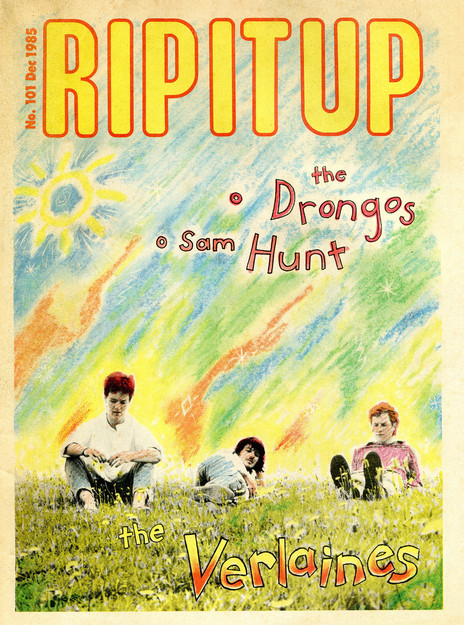

Rip It Up No.101, December 1985. - Rip It Up Archives

In that same week, The Verlaines recorded an album at Mascot Studios. On some of the same songs they had played live they had scored out parts for cello, clarinet and French horn for expert classical musicians to play. Graeme Downes also added banjo and recorder parts. The album was eventually called Hallelujah. It is, Downes admits, rather different from the Verlaines live ...

“I think people who haven’t heard us at all, or who don’t like the raucous nastiness of live rock music, could quite happily like it. I think we’d probably be a bit rugged live for some people ...”

The Dunedin house is cosy, a good fire burns in the lounge. Graeme Downes and his girlfriend Jo bought it last year (the city’s property prices still permit that kind of endeavour) and they’ve been scrimping and saving to do it up. Graeme’s gone up the road to get a flagon of beer. A flagon, mind you.

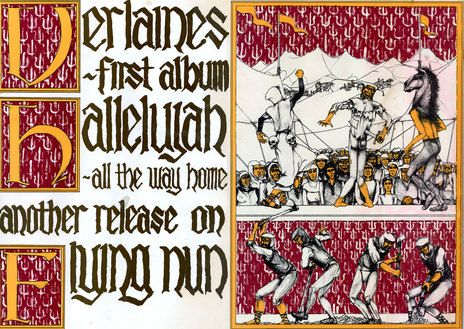

He comes back and apologetically serves up a feed of macaroni cheese. Jo bemoans the frequency with which they eat macaroni cheese, but it’s willingly consumed. After the dishes have been cleared away, it’s time for the interview with Graeme and Verlaines’ bass player Jane Dodd. Jane’s companion and the designer of the album cover (“He badgered us into the title so it would fit his artwork. Hallelujah’s also a good word written down,” Graeme explains.) Charlie Stone, and his dog Blues, listen intently. Well, Blues’s attention wanders a little ...

The poster for The Verlaines' Hallelujah - All The Way Home, 1985 - Graeme Hill collection

The impression you get from Hallelujah is one of a very measured album, not many shots that are fired miss. As they have been for previous records, the Verlaines were well-prepared and knew pretty much what they wanted to do and what they could do.

“That’s not to say that if something turns up when we’re doing it that we think is good we won’t do it,” notes Jane. “Some things we haven’t had very clear ideas on – like ‘Don’t Send Me Away’.”

“Yeah, that was fairly open ...” Graeme agrees. “But the songs were all there and there wasn’t anything to be done to them and all the bits that required other instrumentalists and things were all written out and arranged before we got there. So it wasn’t leaving too much to chance.”

Most bands don’t seem to be able to prepare themselves that well for the studio.

“Yeah. I think it’s important – because it costs a fuck of a lot more money if you can’t.”

One of the features of Hallelujah is the preciseness of the singing, especially considering that it’s not (and shouldn’t be) ever note-perfect on stage and has been, on Graeme’s part, more of a melodic shout on previous records. The two singers put it down to having more time and getting better at singing in the studio environment. But what about mustering the mood for an emotionally intense song like ‘Lying In State’? Graeme looks a little sheepish and Jane answers:

“The vocals I seem to remember being quite an event. It was quite strange because it was the first time we’d seen Graeme really ripping into vocals without a guitar on. Because usually when you’re in the studio you’re holding back on the vocals quite a lot but Graeme really got his act together and just went for it. And it was one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen in my life.”

It’s interesting that the record shows such a different side to the band and the songs.

“It’s just control isn’t it? Physical and mental control,” Graeme explains. “I think a recorded version should be the best possible thing that songs could be. Well, there’s the odd song you take in and ...”

“But it’s still the best,” Jane continues. “Like ‘Lying In State’ would not have suited a clean sound. That song was a live song and the only way it could be done in the studio was to try and reconstruct a live atmosphere as much as we could.”

The Verlaines – Jane Dodd, Robbie Yeats, Graeme Downes.

Graeme: “Doug (Hood) said to me about two years ago that you’ve just got to forget the live thing when you go into the studio, because if you try and do anything like what you’re doing live it’s a pale reproduction of the real thing, because it hasn’t got the power of the visuals and the volume and all that to make it work in a powerful way. So you have to totally forget about that and reconstruct the song almost, as far as how many instruments you use and what you do to get something like the same effect as a live performance.”

Jane: “I think once we’ve recorded a song we play it better live. Even songs like ‘Lady and the Lizard’ that we’ve been playing for a long time, you get to know so much better when you’re recording them.”

Graeme writes all the Verlaines’ songs and he can toss them about for months, sometimes years, before bringing them to the band the usual stumbling block being getting a lyric he’s completely happy with. Sometimes there’ll be some leeway, things for the band to try out, but structurally complex songs like ‘Ballad of Harry Noryb’ come precisely mapped out.

One of the reasons for the Verlaines’ lack of activity this year has been the time demanded by Graeme’s music study at university. He’s looking forward to a lighter academic season next year. His studies have had an obvious effect on his writing – much of the album could be broadly termed “classically influenced”. Jane’s musical knowledge is less heady than Graeme’s but she did learn piano. It’s interesting to speculate on how the Verlaines would have turned out given the same musical bent and no formal training ...

“That’s a tough one ... alternative history,” Graeme frowns. “l don’t know, you see a lot of the differences in terms of structure and things are apparent in earlier songs and I didn’t really know a hell of a lot then. Like ‘Crisis After Crisis’ and even in ‘Death and the Maiden’, changing key in the middle, which was sort of the beginning of trying out different structures instead of verse-chorus-verse-chorus-middle eight-verse-chorus, the normal structured song. The idea of doing it was making a song more narrative, I guess. Unfolding a plot, rather than a structure, which some of them are. But I don’t think I’d be able to write ‘Noryb’ and ‘Burlesque’ and ‘lt Was Raining’ without training.”

Ironically, one effect of Downes’ heavy course of music study has been to make it harder to come up with lyrics for songs.

“That’s the problem we have with my lack of churning stuff out, I haven’t got time to read. I mean you feed off just processing words through your head all the time and I never get time to do it. I just get to process notes every day, not many words. It’s a hassle – I’m almost getting out of the habit of thinking in terms of words.”

A lesser writer might have settled for a lower standard of lyrics and a bit less pain in getting them out, but the standard of Verlaines’ lyrics has been, and remains, conspicuously high. My test pressing of the record didn’t come with a lyric sheet but one or two stand out. Like Graeme, not exactly known as a wild partygoer, spitting out the following words in the chorus of ‘For the Love of Ash Grey’ ...

And in between drinking

Impairing your hearing

Being so bloody uninspiring...

Much of a reflection of your own thinking?

“That’s a difficult one to comment on because it’ll probably mean different things to different people and to me the lyrics aren’t that great in a way. They’re good, they fit in the right places, but they started out by me trying to write a song about a particular idea and that was the best fist I could make of it lyrically. I couldn’t hit the nail on the head.

“It probably sounds lyrically a little bit more bombastic than it was intended to ...”

“It probably sounds lyrically a little bit more bombastic than it was intended to. It was intended to be about the image it used, of someone burning down a library, which the crusaders did on a crusade. People destroying potential knowledge of themselves, lying to themselves. Just totally burying anything they don’t want to know. Which always leads to not getting out of the particular situation you’re in, you come up against the same mistake more and more often.

“It was just really hard to put down. In a way I suppose there’s a lot of songs that are like that, that lyrically go around the same subject. I suppose a lot of writers go around the same subject time and time again and sort of collectively hit it on the head by taking it from all angles. So maybe it’s only part of the jigsaw.”

What’s the ‘Noryb’ in ‘Ballad of Harry Noryb’ – “Byron” backwards?

“Yep.”

Want to explain?

“Well, you know what a Byronic hero’s like – this sort of proud, lonely guy who says [rude gesture with one finger] and wanders off and treks around Europe and is very high and lonely. A Noryb is something like that, he finds himself in the same position of totally rejecting it, but it’s not like a Byronic hero who does it by choice and decides the world is stuffed and goes and does this thing totally on his own. A Noryb is someone who finds themself there and does not make a conscious decision to do that. So he’s sort of like an immigrant in a totally foreign country, which is in the lyrics as well. I think Norybs are probably more common than Byronic heroes in the world.

“It’s important to get across in the lyrics that it is totally defined by fate in a way, that it’s happened that way and it’s not just sort of perverse satisfaction and self-pity. But most of the people who outwardly look like that do delve in self-pity I think.”

Who were you looking at when you wrote that?

“A couple of people who shall remain nameless, neither of whom are totally like that. And there’s probably a bit of myself in it as well – although I’m not like that I think. It’s just a part of the potential ... although maybe anybody’s got the potential to end up like that if the right things happen. Reading Under the Volcano helped, I think – the main character is a modern 20th century anti-hero. He’s quite disgusting until, to all outward appearances, he’s delving in self-pity. But the way he writes the book shows he has no choice in acting the way he does.”

As opined at the beginning of this story, Hallelujah will probably win the Verlaines a new audience, other than the kind of people who go to grotty pubs to hear original music. After all, as Jane says, her father likes it and he’s never liked any rock music before. Is it important to keep the rough edge in the live gigs?

“We don’t have a lot of choice really!” Graeme laughs.

Jane: “I don’t think the Verlaines as they are will ever lose it, unless we dramatically change the way we work. We get pretty excited on stage because we don’t play live very often. And that automatically makes an edge. I always feel on edge.”

Graeme: “You put a lot more energy and enthusiasm into it rather than a controlled getting the notes right. That’s definitely true for me.”

The thing about the Verlaines, the three-piece line-up and all, is that it seems very much a band under control – as opposed to some bands that get away on the people in them ...

“Well I think we’ve got three people who are absolutely dedicated to not letting it get away on us,” Jane affirms.

“We’ve got one person with absolutely no choice!” laughs Graeme.

“But I mean I don’t think there’s any conflict in the reasons people are doing it,” she continues. “They’re doing it because of certain criteria, because it’s good fun doing it, and we all realise that if we play too much then it would stop being good fun.”

So you consciously put limits on it?

“It doesn’t even have to be very conscious really. It’s just feeling that if we’ve just done a lot of gigs then we won’t really feel like doing another one. We won’t be too excited about doing it.”

Do you practise often?

Graeme: “I’ve been too busy this year – apart from the record I haven’t had time to do anything really. But next year should be good. I’ve only got four papers to do, so I should be able to do lots of things. I’ll be able to spend two hours a day writing songs, which will be good. I can churn out music nearly any time I like, but I have to sit down and work on lyrics.”

So what’s planned for next year?

“A lot of practices first. In a way we’ve been pretty slack. It’s taken a lot of work to organise the record I suppose, in terms of actually going up there and doing it, rehearsing it, writing it out, organising it and then doing the organisation for the other end of it has taken most of the time.”

Jane: “We’ve put a lot of hours into business that’s not actually involved with playing, organising things. It’s taken quite a bit of energy this year.”

How do you feel about the non-musical side of the band, would you rather be without it?

Jane dodd: “I’m pretty wary of situations where bands tend to lose control over what they’re doing”

“I’d rather it didn’t have to be done. But if it has to be done I think I’d rather it was the band that was doing it. I’m pretty wary of situations where bands tend to lose control over what they’re doing because they’ve got someone else deciding things for them. Autonomy is a pretty big point.”

“A managerial person would have to be pretty well picked,” notes Graeme.

“Yeah, a managerial person would have to be someone who was as much a part of the band and shared exactly the same sort of ideas and principles as Graeme, Robbie and me,” Jane agrees.

You seem to get through things pretty well anyway.

“I think we get through things because there’s a lot of people in the country that make it really easy to get through things. Like basically it only takes a phone call to Auckland to say we want to come up and do a gig. Having a network of people around the country like that, it just means that basic things in organising are just made so much easier, because there’s all those people on the other end happy and willing and keen to do things for you. And I imagine the same thing happens the other way people come down here and they don’t have any hassles about accommodation and they can borrow gear if they need to.”

“It’s good on the record side too,” Graeme continues. [Roger Shepherd is] “working really hard and it’s starting to look very organised. It just works both ways, I mean Flying Nun is really working hard at getting everything rolling with the record and Roger says, ‘Get us some photos, get us this, get us that,’ and because Roger’s been really motivated we think ‘Fuck, better do something.’ It’s a really good atmosphere at the moment I think.”

Music isn’t your job at the moment – would you like it to be?

“It depends on what you call a job ...” Jane ventures. “What’s a job?”

Well, something that supports you and pays the rent and buys flagons of beer ...

“No, I can’t imagine that.”

Graeme: “I can imagine the band actually paying us money. We don’t earn anything at the moment – it goes into expenses and recording costs. I mean we haven’t even got a full set of gear between us yet. When it comes down to it, we’ve got a lot of things to buy before we get any money, but I can see the day if we manage to stick around for a wee while yet that we could be in a position of getting the occasional bit to help the rent along, just a wee bit, without the thing getting any bigger than it is now.”

Jane: “Yeah, the whole thing we were saying before about not thrashing it is very important. And if we can make money without thrashing it then that’s wonderful!”

So goes the Verlaines. The very model of the kind of group they are. Robbie Yeats has put a firm end to the band’s rotation of drummers and they’re set to do the things they want. The trip to England, naturally, is an attractive goal, and has been put a little closer by the Chills getting there and finding encouragement. Graeme thinks maybe it’ll have to wait until 1987.

The Verlaines haven’t made a bad record yet, but Hallelujah is exceptional if only because it’s so fulfilled – it does what it sets out to do. But the use of dynamics and “narrative” song structures are part of a sophistication that, in this context, is unique. It’s summed up in the closing ‘Harry Noryb’, a song that speaks, roars, wails and finally whispers an ending.

“It’s a bit funny doing a Verlaines interview,” I said to Charlie afterwards. “Because the music’s pretty eloquent in itself anyway.”

“Put that in the story,” said Charlie.

First published in Rip It Up, issue 101, December 1985. Thanks to the Rip It Up Archive and Papers Past.

--

The Verlaines – Hallelujah All the Way Home (Flying Nun)

Review by Russell Brown

From Rip It Up, December 1985

It’s 6.18 am on a Monday. I am sitting on the roof of Rip It Up’s office, looking down three floors to Queen St, writing a review of the Verlaines’ album. The city is just beginning to move, a street cleaner waterblasts the footpaths before they’re full of people.

The Verlaines, Hallellujah - All the Way Home (Flying Nun, 1985)

The first thing about Hallelujah All the Way Home is that it’s yer actual high-fidelity record and needs to be played LOUD. Not that it’s all noisy or anything, but, like orchestral music, it depends on dynamics to create its mood. It should be played loud enough for the guitars to bash and crash around your ears, enough to draw a sharp contrast against the quieter passages. The closing track, ‘Ballad of Harry Noryb’, pretty much sums up the album in this and other respects by the time it wails plaintively off into the void, a hail of huge electric guitar will have come crashing down on you, the music telling as much of a story as the words.

Narrative song structure is a feature of the record; the words and music do a kind of duet on telling the stories. Roles get blurred, the music’s a bit literal and the words a bit musical. And they can hide away little secrets – ‘Don’t Send Me Away’ is a jauntily phrased little folk tune that bears some fairly pungent observations (and these are his friends Graeme Downes is writing about). The most abrasive and propulsive track is ‘Lying In State’, a song written back when Downes probably wanted to be The Clean. And when he still had problems on the romantic front: “You don’t talk, and what’s worse / You take your car keys out of your purse,” is a very nice couplet, don’t you think? As has always been the case with the Verlaines, the lyrics generally read well on their own, a fairly rare thing in rock ‘n’ roll.

The preparation before the recording of this album was comprehensive and it shows. There’s a very strong impression that the Verlaines achieved pretty much what they set out to do. They certainly play well, and at least one guest musician was surprised to be handed a written score for her part: “Most bands just say ‘play something over that!’”

The result is that as well as the sounds being right, touches like the horn line in ‘For the Love of Ash Grey’ are just so. If the band lost anything in spontaneity, they more than made up for it in simply getting their ideas across so bloody well. Also, as the sleeve art makes clear, Hallelujah is a whole beast. If you play it from the start of side one to the end of side two, it announces itself, unravels and finally elegantly resolves itself in ‘Noryb’ (even if the resolution is only resignation).

A bonus too: it makes seeing the Verlaines live a lot more fun – you know the songs and can latch onto the structures and note and enjoy the differences in the live beast.

Okay, I like this sort of thing, but I think on any terms Hallelujah is a great album. I think it’s my favourite New Zealand album ... and the old city’s beginning to grrrowl along with itself ...