One fateful day in 1983, Wellington based graphic design student Michael Hodgson answered the phone and agreed to provide overnight accommodation for Christchurch musician Andrew Craw. During his stay Craw described other music work he was doing with Angus McNaughton in Christchurch, which involved a 2-track recorder and effects.

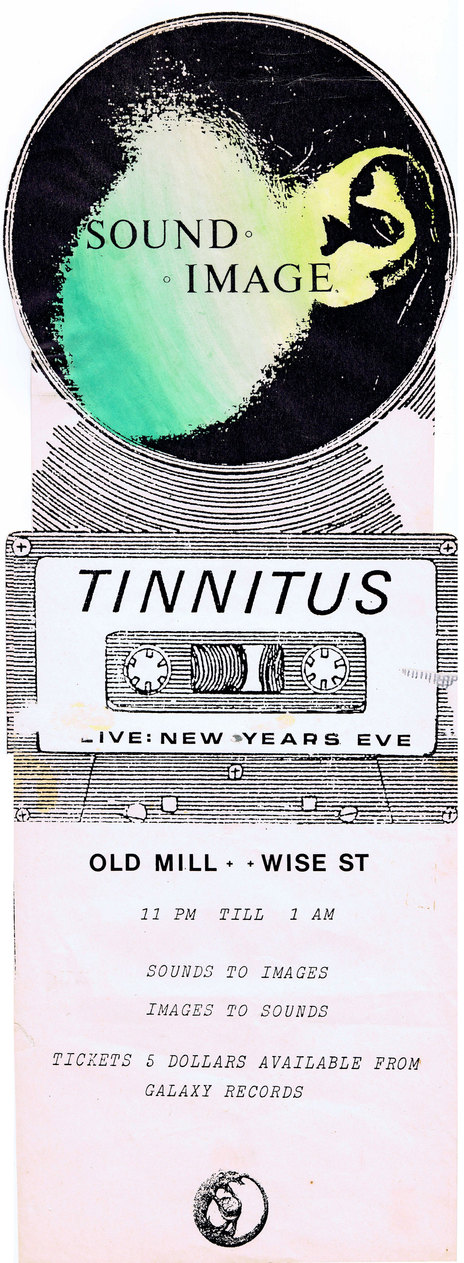

Hodgson was intrigued. He flew down for New Year's Eve of 1983/84, met McNaughton, hung out, played with the equipment and “got the bug”. He returned to Wellington, promptly quit his course, packed his bags and relocated to Christchurch.

Their first recordings came from the fun they were having using pots and pans, guitars, found sounds, distortion pedals, vacuum cleaners, and one of the first digital delay pedals.

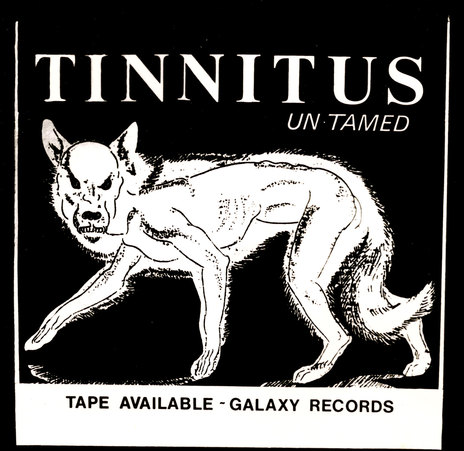

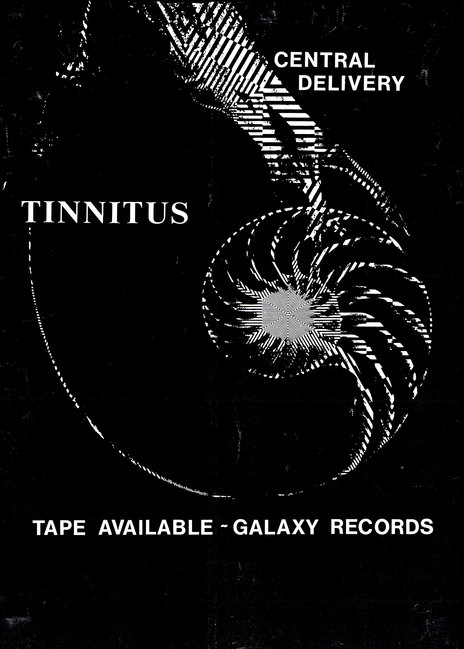

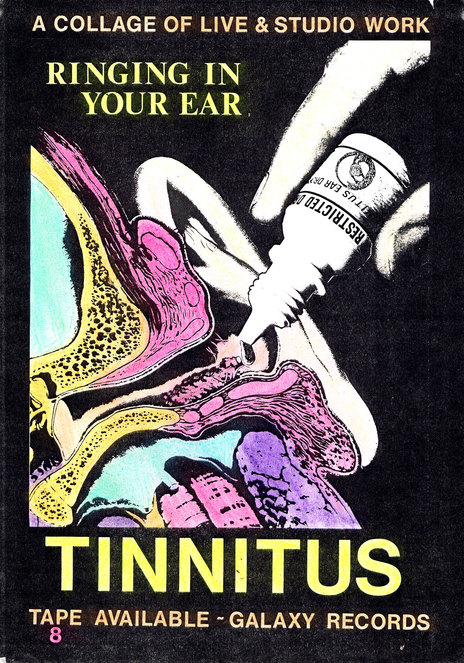

McNaughton and Hodgson then began a period of experimentation at Hodgson’s flat in beachside Sumner. Their first recordings came from the fun they were having using pots and pans, guitars, found sounds, distortion pedals, vacuum cleaners, and one of the first digital delay pedals. They collated the material they had been working on and released the first Tinnitus cassette in 1986.

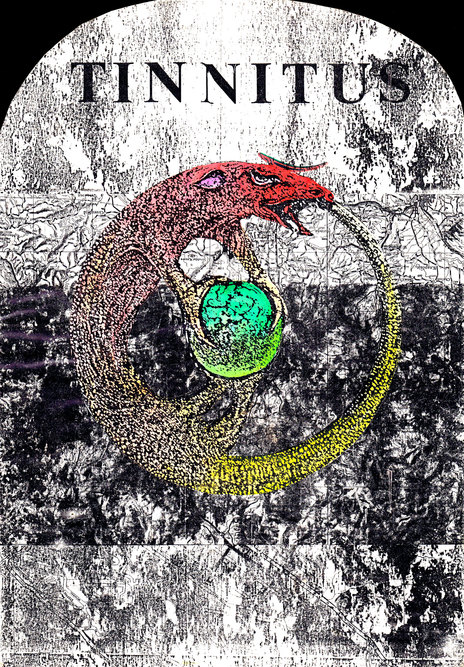

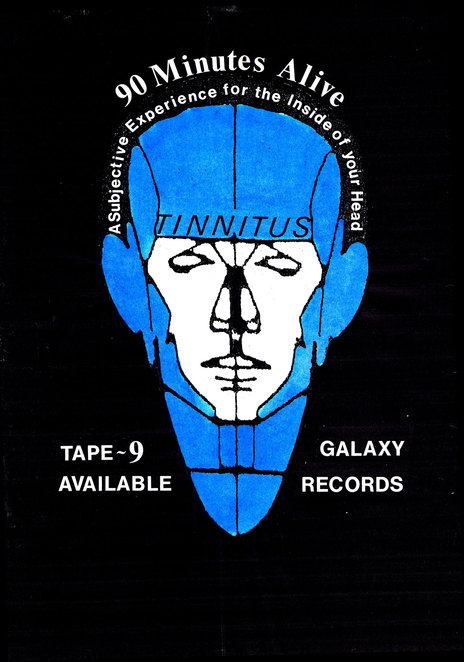

The name Tinnitus came about from a tape recording about the medical condition of tinnitus, which was incorporated into one of their earliest recordings. Hodgson: “We liked the idea that the experience was a very subjective experience. Therefore, what we were doing was for us, but if you heard it, you’d have your own take on it.”

In mid-1986 Hodgson met fellow film student Ashley Turner. Turner played clarinet, trombone, saxophone and percussion, and had previously played in Auckland with Fishschool and the free-jazz collective Coalition. Hodgson gave him a Tinnitus cassette; he was impressed. They ended up sharing a house on Avonside Drive, where Tinnitus was formalised as an entity. Later Gary Stevenson and Shaun Collins would be members.

As a collective Tinnitus were interested in bands like Throbbing Gristle, Coil, SPK, The Anti Group, the On-U Sound label etc., but their music was not derivative of any of the aforementioned. “We were more ambient or soundscape than industrial,” says McNaughton.

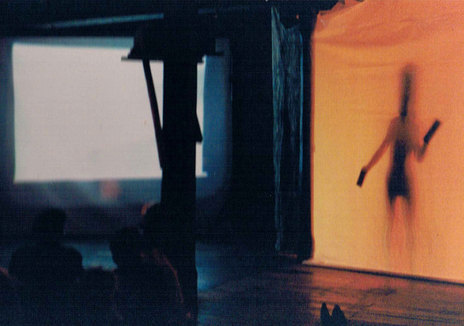

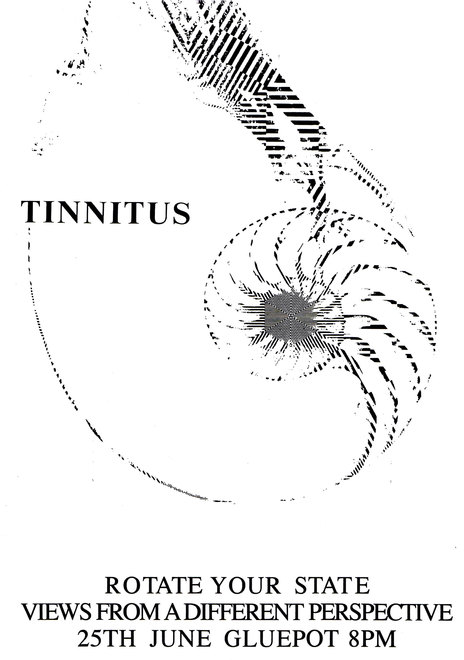

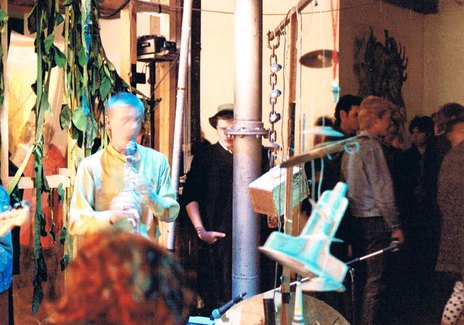

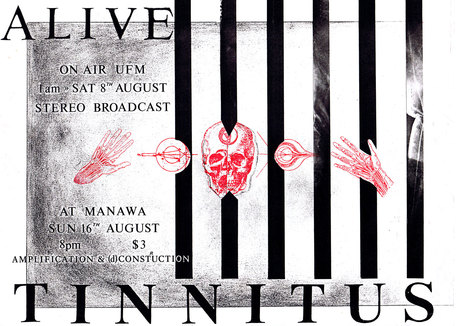

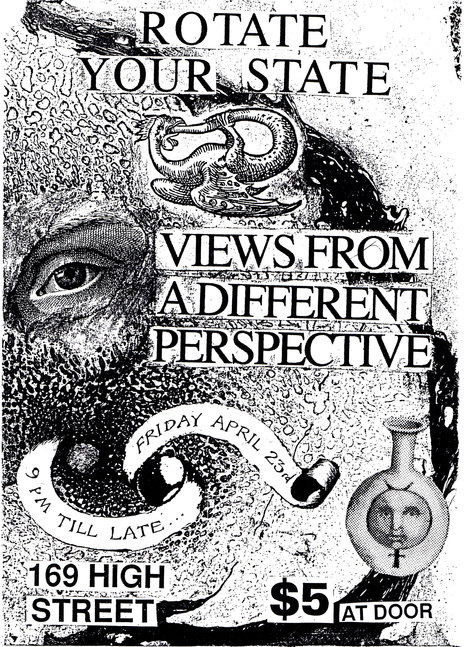

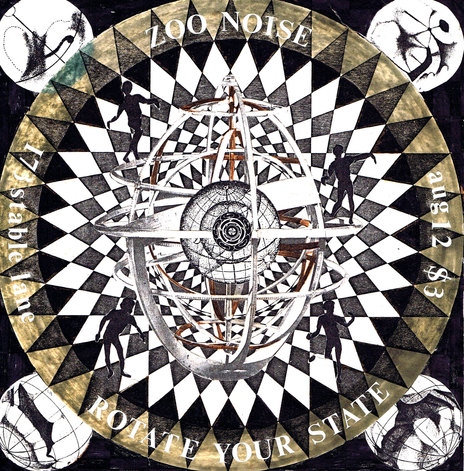

After seeing a performance by American experimental artist Richard Lerman, Hodgson realised that playing live didn’t need to involve a stage and could be anything you wanted. In August 1986 they set up a pile of sound and film equipment along with wired up metal sculptures and paint in an art gallery and played “live” for the first time.

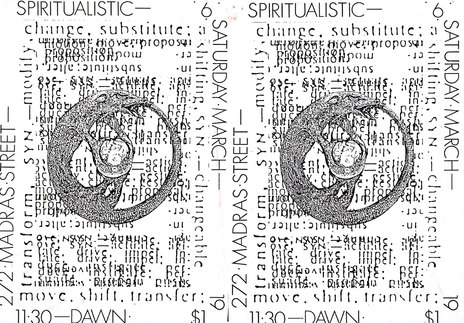

McNaughton moved into the old Spiritualist Church on Madras Street and eventually Tinnitus’ sonic experiments in their own large space, free of time constraints, led to more advanced performances during 1987. The Church performances were intense ritualistic affairs with the walls painted dark colours, giving the impression of a wet dark atmosphere, “an arty industrial cavern” as Shanti Freed, a friend of the band recalls, “with lots of piping, scaffolding and found objects.”

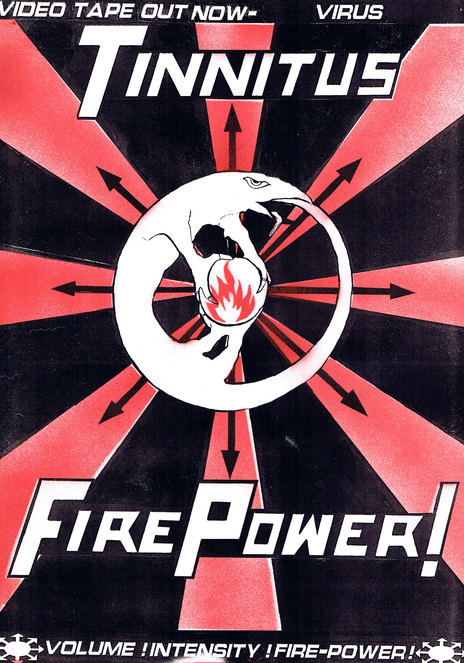

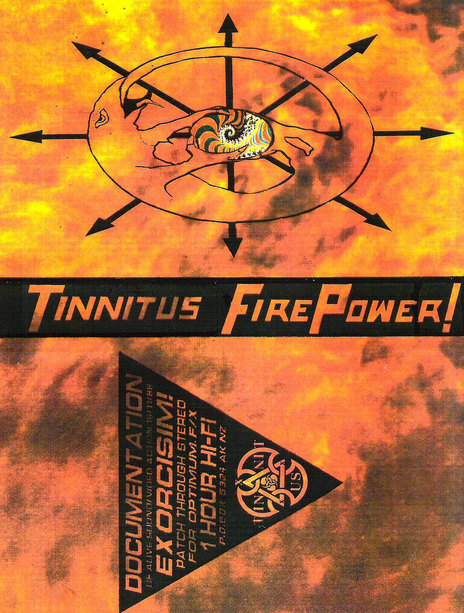

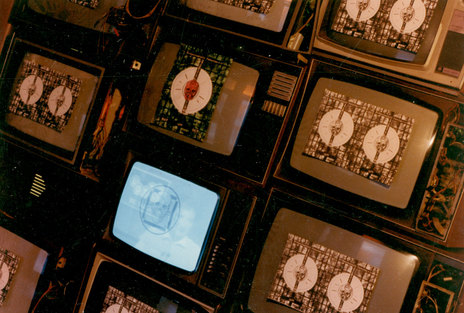

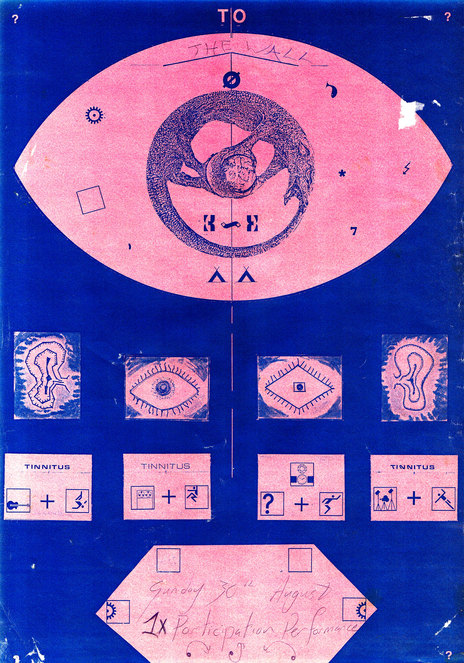

Numerous other collaborators would come into the Tinnitus fold for performances and audience members walking into a Tinnitus performance would be enveloped by a loud sound system accompanied with multiple visual projections, oscilloscopes, rotating cameras, or sometimes dancers or painters. A backing tape would be played with live percussion and other instruments fed into a dub matrix, as well as feeding in signals from contact microphones they placed throughout the venue. Tinnitus had an inclusive philosophy — the audience was encouraged to engage with the audio-generating elements in the space.

Hodgson and Turner created the projections, slides, images and scratch films. They felt the creation of visual-scapes and immersive soundscapes were a natural progression. Turner notes, “Our composing methodology was about creating something with a core rhythmic pulse that had a sonorous tone and then building on that.”

The music could be explosive and dissonant but it also had a significant aspect of contemplation to it.

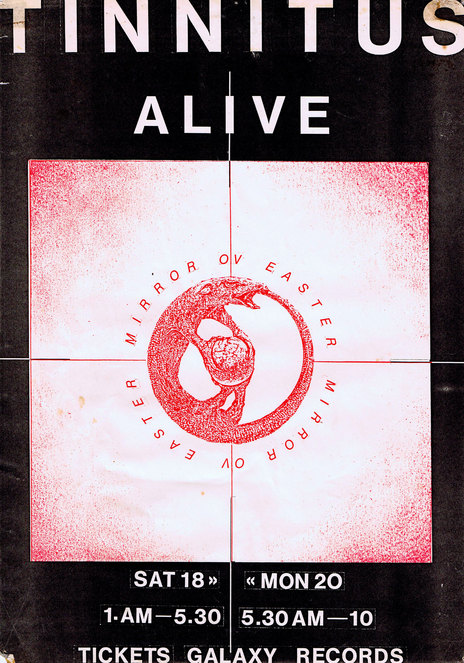

The total sensory effect of the visuals and sound was mesmerising and these events in many ways prefigured the rise of the dance parties in the late 80s and early 90s. The events could start at 10pm or midnight and go through to 6am where Tinnitus would play a set for an hour accompanied by other artists or bands, with more conventional dance music.

A fundamental part of Tinnitus’ modus operandi, both live and on their released recordings, was their development of dynamics and timbre in exploring sound textures. A library of cassette loops would be introduced into situations where Casio keyboards, brass instruments from Turner and a drum machine would be used with other additional noises. The music could be explosive and dissonant but it also had a significant aspect of contemplation to it, with parts of their releases having a distinctively meditative feel to them. Tinnitus had multi-levelled themes in their work but notable components were the aesthetic of time or journeying and a critique of Christianity.

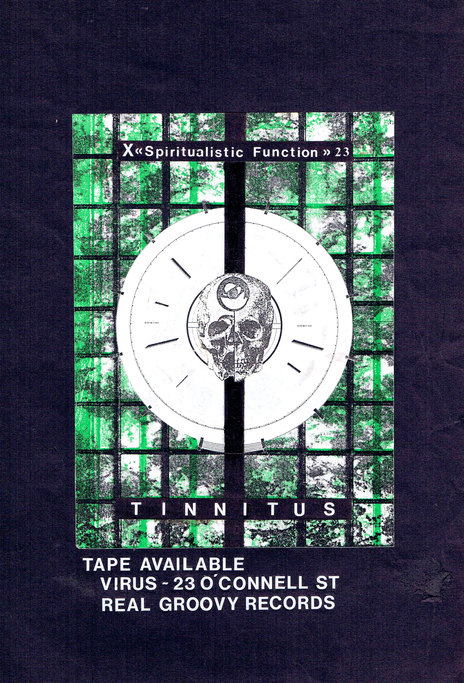

Tinnitus were adept technicians as well as artists, incorporating the latest audio technology when they could afford it, and setting high production standards for themselves from the start. Spiritualistic Function, released in 1987, is a landmark recording, and shows how quickly Tinnitus had become masters of sound editing and recording. None of the ideas or textural components in their soundscapes would be overstated nor overstay their welcome, whether they be a sequenced drum/bass line or found sounds (eg. a jet engine, birdsong, or bell).

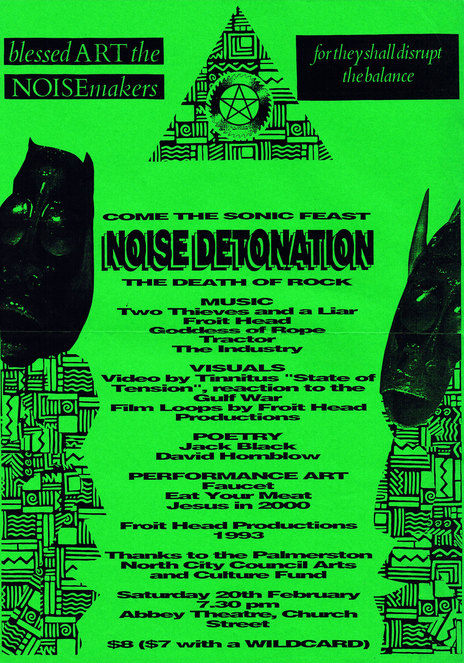

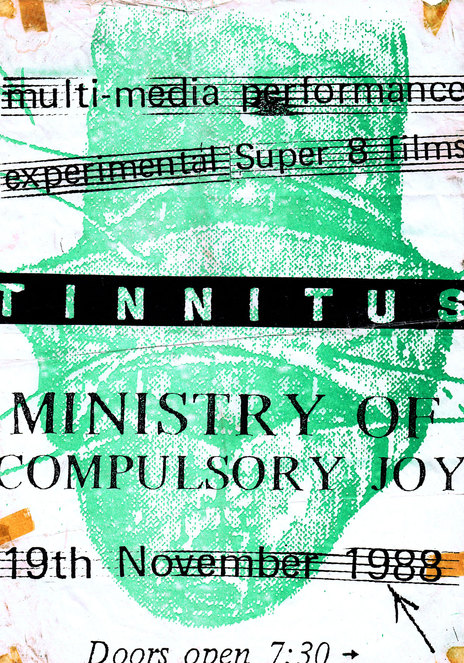

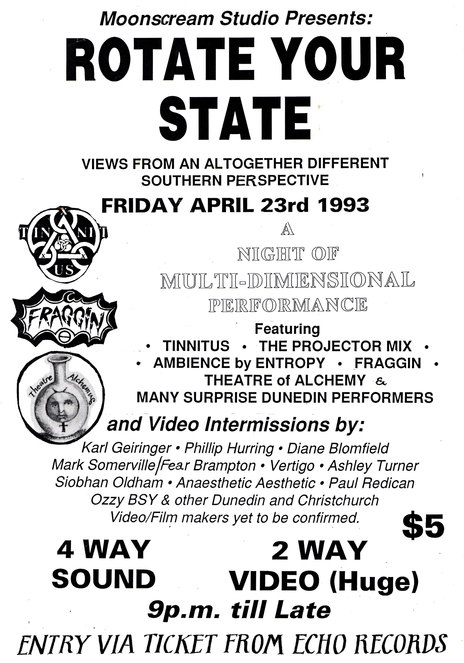

By 1988 Tinnitus had moved to Auckland and were established as a popular artistic draw around New Zealand. Four years on, by 1992 they had released 13 cassette albums and played a large number of live shows. ‘Function 2.3.2’ was on the Failsafe label’s compilation South (1987), they appeared on the 1992 Freak the Sheep Vol.2 compilation, and the same year, they also released the album Futures Past on Flying Nun.

With each member becoming more embroiled in their own projects, their last performance was in 1993. They played a show in 1997 for an Opus Locus release then retired again from public view.

In the following years Hodgson concentrated on his multimedia work, firstly as The Projector, where he would do visuals for many bands. He is now based in London and continues to perform with Pitch Black, which he formed in 1996 with Paddy Free. McNaughton (with partners) founded Incubator, a recording studio in 1990, and since then has become one of New Zealand’s most prolific and acclaimed sound engineers and producers, working with Headless Chickens, DLT, Dimmer, Naked and Famous, Pitch Black and many others. He now teaches at MAINZ and is setting up a new mastering studio in Auckland. Turner is now a designer who also lives in Auckland and is active in the Auckland art scene.

While Tinnitus never enjoyed the kind of public profile and critical acclaim that their work deserved until the end of their life, they made an important contribution to the development of the independent music and arts scene of the 1980s and 1990s. Key components to their artistic success were their intrepid exploration of sound and visuals, audience participation and their fierce independence and resourcefulness. Everything was DIY – from recording to cassette duplication to the retail displays at record shops. And the sonic language they developed out of their experimentation was exemplary.