Before going out on her own as a children’s artist, Claudia was (and still is) the vocalist and co-producer for dance music duo Substax. But after her first child was born, something had to give. With a deeply musical ancestral lineage, the crossover from dance to children’s music seems like a destiny that couldn’t be halted.

Her mum, Denise Gunn, was one of the six singing Bulte Sisters. Her father played drums and saxophone in long-running dancehall band Bulte’s Orchestra. Each generation grew up surrounded by music.

Claudia Robin Gunn’s reach is international, with 15,000,000 streams on Spotify by 2024

“The first music I remember hearing would probably be something played on my parents’ record player,” remembers Claudia, “like a Beatles album, Joni Mitchell. At all our family events and birthday parties, everybody would sing in harmony. So, a mixture between some old classics on records, Mum and her sisters singing, and my dad belting out a tune while he demolished a wall in our house. Also probably some Eric Clapton, or Cream, maybe Santana … ”

Denise was a songwriter and musician too, playing in bands like PG and the Hot Tips, and Blue Cockatoo in the 1980s and 90s. She juggled live gigging with university study, working part-time and parenting, showing her daughter what was possible. Reading Denise’s songbooks with her siblings, Claudia remembers loving the songs ‘Moonshadow’ (Cat Stevens), ‘Islands in the Stream’, (Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton) and ‘500 Miles’ (The Proclaimers).

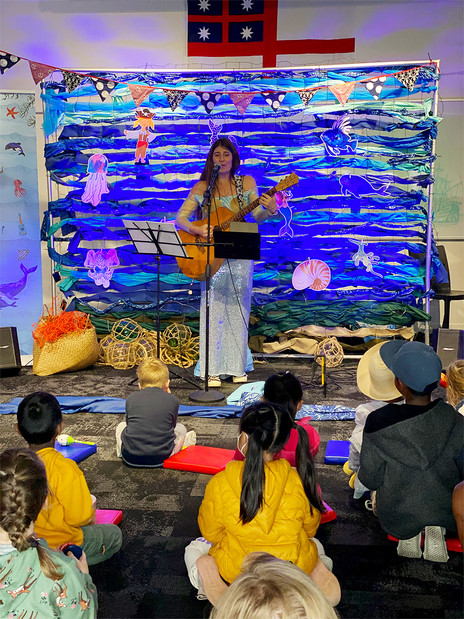

When she was the same age as the kids she sings for now, Claudia was a confident child. “Quite loud,” she says. “I was quite boisterous, and probably didn’t have any volume control. I wasn’t as brave as my sister, though. My sister Melissa is a year older than me. She was the kind of kid who would go and help light fireworks, and I’d go and hide by Mum. So, I was brave, but not as brave as my sister. I really liked singing, and I think I didn’t have very many fears. I had one sister just a bit younger than me, Pipiana, and Melissa just a bit older than me, and we were definitely like a gang of three.

“I had a teacher at Kauri Park Primary [Beach Haven, Auckland], Mrs Halkyard, who I really, really loved. She would take us out under a tree in a field and sing, and that made an impression on me. I was part of the Culture Club – we’d call it Kapa Haka now – I loved that. We also had a teacher, Mrs Green, and she played autoharp, which I thought was amazing. I still really want to get one like she played.”

In the summer of 1986-87, following Bananarama dominating the New Zealand pop charts the preceding September, history began repeating itself in the form of the next generation of Bulte descendants. At Waihi Beach’s legendary New Year’s festival, the three young Gunn sisters entered the talent quest to give ‘Venus’ the prize-winning treatment. Their dad, Moss Gunn, recalls they “performed confidently in front of the crowd,” winning them third place.

A few years after that, Claudia auditioned for a production of the musical Chicago at Takapuna Grammar, and was cast as understudy for the Roxie Hart role. When the lead fell ill on the second night, Claudia stepped up for the rest of the show’s run.

“I actually wanted to be an actress first, when I left school. I did a year of drama school. But I really liked singing, and I was writing quite a lot of poetry. I started writing my own songs and teaching myself guitar.” She learned how to use a four-track recorder to aid these endeavours, and easily tumbles into musing about further advancements in music technologies she has kept up with.

Although music was in her blood, she was encouraged to chart her own course independently.

“I take my hat off to Mum,” Claudia says, “going out and playing three or four times a week sometimes, and she did some voice teaching. But Mum didn’t teach me; probably just a mother-daughter dynamic. I understand that now, because I have a teenage daughter, but at the time I thought Mum would help me more. She literally wrote just three chords on a piece of paper and said, ‘Just work it out. I taught myself, you can teach yourself. If you want to do it, you’ll find it yourself,’ which was actually really good advice because it’s true. When someone hands something to you, with no effort on your part, you don’t appreciate it and you don’t really even take it in. So, I started off with three chords, and I’d learn a new chord, and write a new song including it so I wouldn’t forget the chord. That was my way of getting my head around a guitar fretboard. That worked through a few early songs.”

writing at night trying to get her children to sleep encouraged Gunn to write lullabies

While at university she was in a band called Touchpaper, often playing at Temple Bar in Queen Street and spending all her money on tech gear. She remembers being very loyal to all the bands she worked with, at the cost of ever leaving the country. It was a pre-digital world of old school methods, actual magazines, and going into studios, and – from her eventual position as singer and producer with Substax – she didn’t imagine motherhood would change that when its time came.

“I probably was a little optimistic about the impact of being home with nappies. There was the whole baby versus sleep thing. I literally don’t think I’d read a single book about what you do when they arrive and the fact you can’t make them sleep. That’s what really got me writing lullabies, and onto the children’s music pathway. It was literally just, nothing would work unless I’d sing, and singing was the only thing I could do, and I didn’t need to have a phone battery or anything plugged in.”

She’d often sing any old thing that came to mind, but she began freestyling new songs, and the keen technophile had everything needed to capture these at hand.

“I’d record them as memos, and – because I had my studio, hidden under the bed, I hid guitars in cupboards – I just needed to find time and space and no toddlers, and plug everything in. So, I did a few demos, and when Arthur Baysting put out a call out with APRA for the first Children’s Music Awards, I sent one or two unreleased demos in. I was knocked over with astonishment when I co-won that songwriting award the first year they ran it.” (In 2008, Gunn’s ‘Lullaby Time’ was co-winner with Craig Smith’s ‘Wonky Donkey’ of the inaugural award.)

“Julie Wylie [MNZM], who’s an absolute bastion of children’s music and teaching in New Zealand, had a whole bunch of her students as a choir, and they sang my song in the Christchurch Town Hall. Mum came with me, and it was a shivers-down-your-spine moment to hear the kids sing the song back to me.”

Another baby came a year later, and Claudia remained “in the thick of motherhood”.

“I take my hat off to musical mothers whose careers are already in motion when they have babies,” she says. “I look back now and think, it took me so long to get going, but I was lucky I had my own gear that I could use at home. That allowed me to work on the songwriting when I had time, which was always in the night, hence why I wrote so many sleepy songs, but I won the APRA songwriting award again in 2010.”

She was still writing with Substax. Her first solo album, Little Wild Lullabies, was released in 2016 by her own production company, Little Wild Music.

“Some things do take a long time, but it was definitely demonstrative of the fact that if you keep putting one brick further along, you’ll make a pathway. Even if you’re not sure where that pathway is going, you’ll definitely have somewhere to walk.

Gunn had a breakthrough: making music “has to dovetail in with the kids”

“My kids were a bit older at that point, but I don’t think it’s ever easy with kids. They definitely keep taking time, because you’re incalculably attached to them. After thinking I had to have some time out from the kids to make music, I finally had a breakthrough at some point along that pathway. You have to make it with them, it has to dovetail in with the kids. At home, it’s better for them to be part of it. Let them climb on the guitar. When you let it get completely playful, that’s definitely the way I found to keep doing it. I’d sometimes just turn on my voice recorder and sing them a song I’m working on, and ask them questions, and let them help me finish it.

“That’s definitely the way I found to keep doing it, and not let the fact your life has changed and you have different responsibilities curtail your creativity. You can find ways to keep translating the experiences you’re going through in a musical way that is sympathetic and supportive of your life – and hopefully also is something that resonates and will have some relevance and meaning to your fellow humans who may be experiencing the same funny moments, or hard moments, or exciting, or overwhelming feelings of adoration and joy, or, ‘Oh, my God, I can’t get through this,’ or everything in between.”

When she first got into the kids’ music scene, Claudia had no idea about what she calls “this really beautiful renaissance of artists bringing all of their musical history in different genres into the space intended for children”.

“Back in 2005-2006, I was mostly inspired by other artists I really liked at the time: Beth Orton, or Dolly Parton. Probably bringing that singer-songwritery sound into the work is really more my jam. I did discover some lovely artists whose work I’ve definitely taken as an inspiration: Frances England, Elizabeth Mitchell, and Ella Jenkins is the third point in that tri-pointed star.

“And as I got to know Arthur [Baysting] more, I got to know Justine Clarke’s work. Arthur and Peter Dasent did so much writing for her, and I really love Arthur’s writing styles. I only got to know more of his work (sadly) after he passed away, and then I discovered what an absolute treasure trove he had been creating his entire life. So, mad respect for our local heroes.”

Claudia further acknowledges Suzy Cato as a big influence, particularly for her work establishing the Kiwi Kids Music collective, which she cites as an essential source of networking and community building. But, before that networking happened, Claudia was finding inspiration on her children’s bookshelves.

“In the early days too, I came across a lot more children’s books than children’s music, So, writers like Margaret Mahy, Joy Cowley, Pamela Allen; The Little Yellow Digger, My Cat Likes to Hide in Boxes. Lots of the songs I’ve been writing start more from the storytelling writing perspective, and then they’re musical, because I always hear melodies, and I put them into a rhyme scheme that suits being sung.”

The combination of influences creates music that’s not only embraced by kids, but their kaitiaki too, making Claudia one of those secret love weapons that make raising children more natural, and joyful.

“the most successful children’s music, probably parents don’t love it”

“The key to creating music for kids – that parents will love too – is relatability. So, tunes that feel familiar but they’re new, but they maybe have some quality about the texture or shape of them, the sonics or the acoustic beat. Whatever genre you’re going for, you’re essentially making music. You’re essentially remaking music with a message, a story and visual imagery in it that relates to a child’s world, but you are putting the wallpaper on that would suit whatever club or space the parents want to be in. You’re reducing the jarringness.

“In actual fact the most successful children’s music, probably parents don’t love it. If you want to get critical acclaim, maybe make what parents will love; if you want to just get numbers, I guess everyone follows the crowd. When you're trying to do music mostly like I’m doing, it’s not the fast lane. It’s definitely the slow lane, but it’s kinda like the little niche where I like to hang out because I don’t want to be in the pack.

“There’s nothing worse than music getting a bad name and parents wanting to shut it off, because then the child is deprived of the music. If you build the music in such a way as it’s got a bit of charm, or a bit of zest, or a great bassline, something about it musically is really satisfying, that means the children get the benefit of that music, and it doesn’t hurt their parents’ ears, and that’s mostly good for the child. That might seem like you’re catering to the parents’ taste, but you’re doing a service to that family by creating something they can enjoy together, and isn’t something that makes people reach for the remote.”