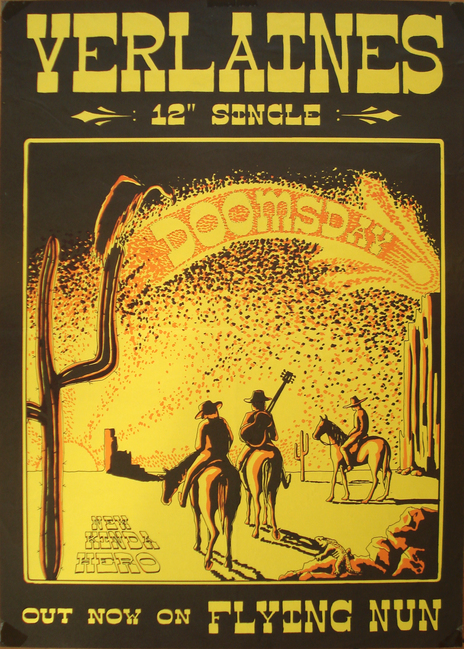

After establishing themselves with groundbreaking albums for Flying Nun, the band signed to Slash in the US and, managed by Downes’s wife Jo, they toured the US and Europe on the back of the albums Ready to Fly (their Slash debut in 1991) and Way Out Where (1993).

If album sales were never quite what they might have been – his solo album Hammers and Anvils (2001) was released in the US on Matador two days before 9/11 – Downes’s credibility was always high among college radio audiences. He was philosophical about the band’s lack of success, returned home and simply rebuilt his life and career and continued to work.

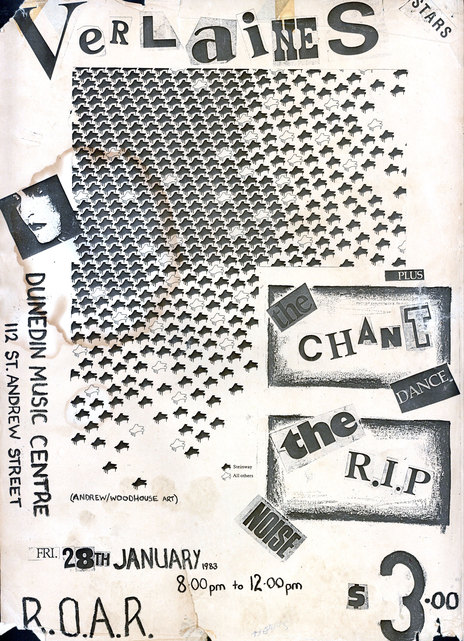

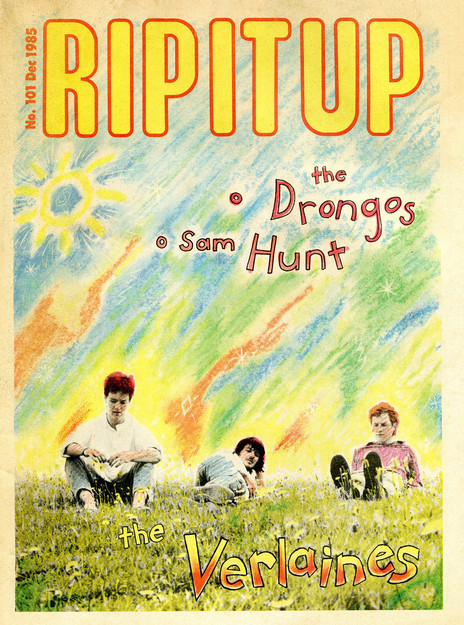

There was always something different about Downes’s approach, in large part due to his classical background, ambition and literary songs. Downes and The Verlaines were always a band apart and they staked their claim early on the multi-act Dunedin Double released in July 1982.

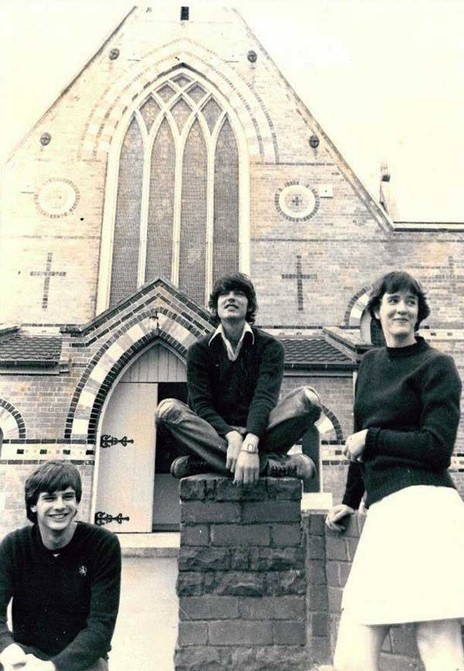

But by his own admission when The Verlaines first started, “I knew about music theory and complicated chords and a lot of classical theory, but I didn’t know diddley-squat about rock music and what made a rhythm section function.”

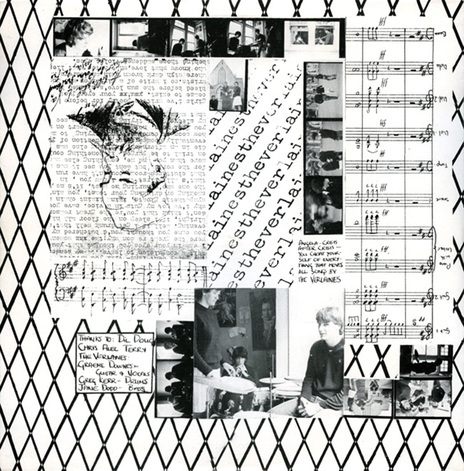

He learned quickly. But he also nailed up his outside interests right from the start. Downes’s collage art for the band’s side of the Dunedin Double gatefold sleeve had his score for ‘You Cheat Yourself of Everything That Moves’ (one of three Downes songs on their side of double set) with a picture of the 19th century French symbolist poet Paul Verlaine and some song lyrics.

It was a measure of Downes’s intellect – and musical intentions – that he named the band after the poet and on their early classic ‘Death and the Maiden’ he name-checked him and his young poet-lover Arthur Rimbaud. The song took its title from one of the abiding themes in literature, music and art (notably the painting by the Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele).

The B-side of the ‘Death and the Maiden’ single was ‘CD, Jimmy Jazz and Me’ which referred to Claude Debussy, James Joyce, and Downes in bohemian Paris “to write of the sea”. Few bands on Nun, or indeed anywhere, would be quite so intellectual straight out of the gate. But Downes sold the songs on stage.

Few bands on Flying Nun, or anywhere, would be quite so intellectual straight out of the gate.

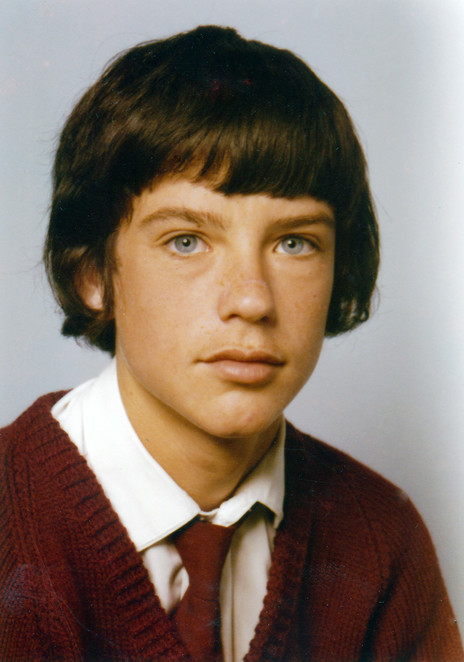

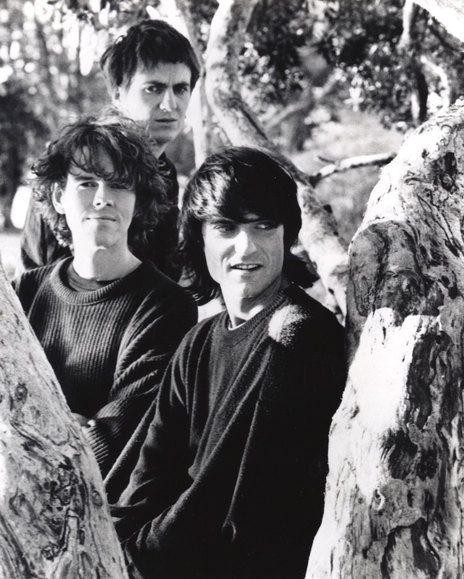

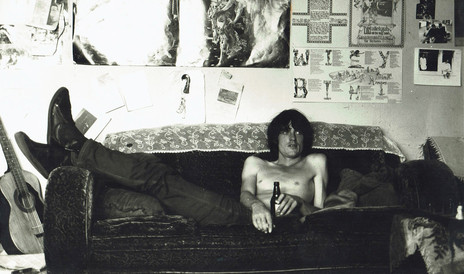

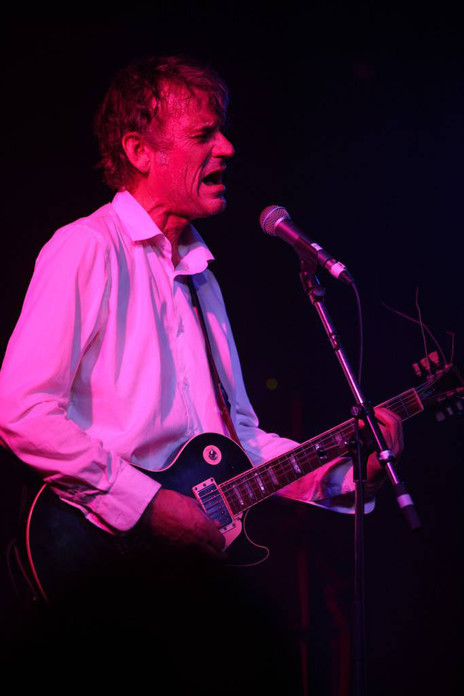

Matthew Bannister (of Sneaky Feelings, Dribbling Darts of Love, One Man Bannister etc), in his memoir Positively George Street, captured the essence of Downes’s presence at that time: “Graeme was smouldering and Byronic. He had gaunt cheekbones and eyes of the clearest blue, which he set off by playing in a white shirt and sometimes a red bandana round his neck.

“He whipped himself into an expressionistic frenzy on stage and dropped literary references by the bucketload . . . his classical training gave him a broad palette and all his songs were structured carefully with an ear for clever harmonic twists and sidesteps.

“They also did a lot of speeding up and dramatic pauses and stops which gave them impact … I was amazed that they weren’t more popular.”

In the first issue of the Flying Nun fanzine garage, Ralph E Stanton wrote “on stage Graeme Downes burns so white you think: God he can’t go on like this. Won’t last the distance. Going to burn out. Fast. He throws these wasted Keith Richards-like shapes, a boy seemingly carrying an unmanageable burden. “Therein lies the Verlaines’ spark.”

That furious energy and commitment – rare among bands perfecting the art of cool detachment and a non-committal attitude – also set Downes apart.

“I’m very influenced by classical music,” he said at the time. “What I’m trying to do is write songs that inject a little bit of drama into rock music. If you want to make something sound dramatic you start in one key, go away from it and come back to it.

“That creates tension. In country and western music they lurch up a key, play another verse and then change up another. Totally aimless. It grates. University has taught me to set high standards.”

And he did, not just in his complex but always engaging songs, but in the presentation of the Verlaines’ albums.

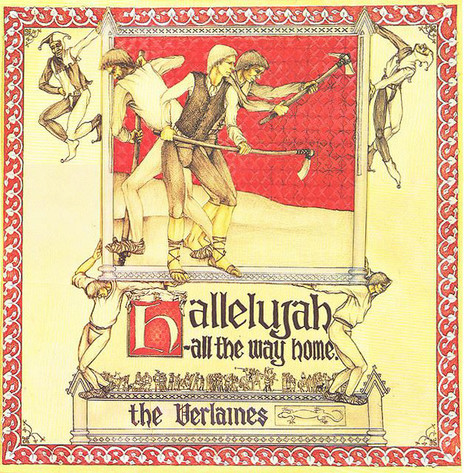

When the money and opportunity came his way the recording quality went up and the band’s early Flying Nun albums Hallelujah All The Way Home (1985) and Bird Dog (1987) came in gatefold sleeves with lyrics and elaborate art work.

But that Gothic gloom of Dunedin “under a pot-lid sky” (as he wrote on ‘I Am’) and the landscape around the city was frequently present in his extensive canon.

Some regard The Verlaines’ music as depressing; if anything, Downes is a great romantic – Grant Smithies

As Grant Smithies noted about Bird Dog in his book Soundtrack: 118 Great New Zealand Albums, “On Bird Dog and elsewhere, Downes’s lyrics frequently touch on three pet subjects: death, alcohol, and the cold remains of love that has smouldered away to ash. That has led some reviewers to write off The Verlaines’ music as depressing – if anything, Downes is a great romantic.

“It’s just that he finds more meat to chew on when contemplating the lonely aftermath of love than when contemplating love itself.

“And death? Do you know any better metaphor for finality, for loss, for the very fullest of full stops?”

And alcohol is the cheapest of anaesthetics for pain.

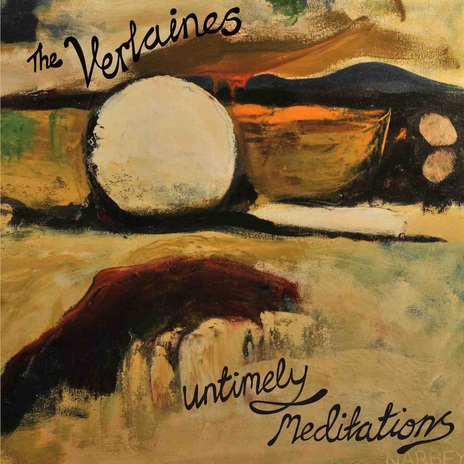

Whether writing about love, life or even politics and corporate capitalism (as he did overtly on The Verlaines’ 2009 album Corporate Moronic), Downes was always a craftsman with words as he bounced between philosophy and rage. As on the angry opener ‘Born Again Idiot’ on The Verlaines’ 2012 album Untimely Meditations, where the protagonist talks to God who says he should have read His book but “you read Nietzsche instead, I’ll catch up with you shortly after you’re dead”.

He referred to that album as “the most criminal piece of work I’ve ever done”.

When I posed the question “if music was denied you, your other career choice would be …” he replied, “Philosophy.”

This from a man who also said Harry Belafonte’s ‘Jamaican Farewell’ – sung to him by his dad at bedtime on Sunday nights – was the first song which really affected him, who considered The Beach Boys’ ‘God Only Knows’ one of three songs he’d love everyone to hear (alongside The Verlaines’ ‘Last Will and Testament’ on Untimely Meditations and Mahler’s ‘Ich bin der Welt adhanden gekommen’), and if he could get on stage with anyone it would be Neil Young to play The Beatles’ ‘Helter Skelter’.

To outsiders, Downes might have seemed an uncommon character in his broad range of interests, but he never saw any conflict.

Of lyric writing, he told me in 2003, “I have always binge-read to get in lyric-writing mood and keep fresh ideas coming – whether it be poetry, literature, philosophy, history, political commentary – there’s no end.

“And of course studying songs by others, or scores of composers. If you think you can write original music in a vacuum you are fooling yourself … For me a good lyric is down to coherence and no padding, no weak lines there for perfunctory reasons. Focus, focus, focus!

“The DNA comes from the music (the right key, tempo, melodic shape, rhythmic ideas etc). It doesn’t matter how you go about it, but in the end a good song is music and words that seem utterly inseparable.”

“A good song is music and words that seem utterly inseparable.”

Recently, when noting that for more than a decade the words come first, he quoted James K Baxter’s line that the only way to get a poem off your back was to write the damn thing down.

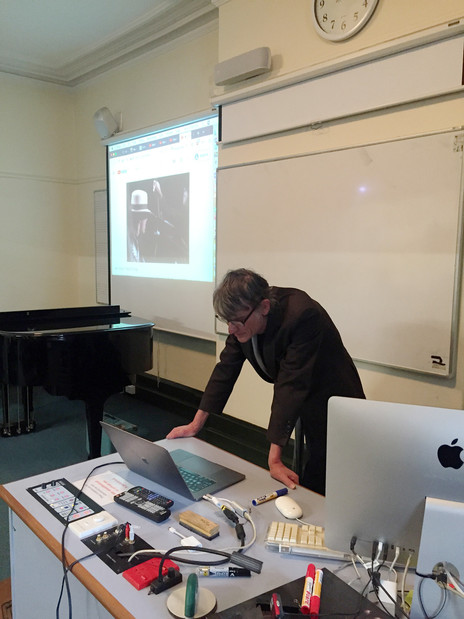

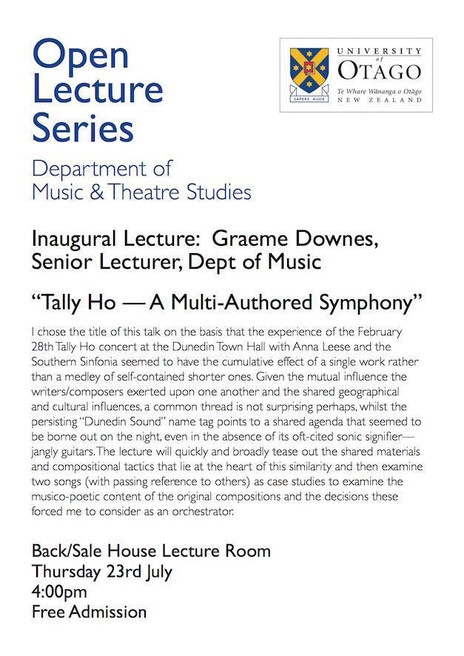

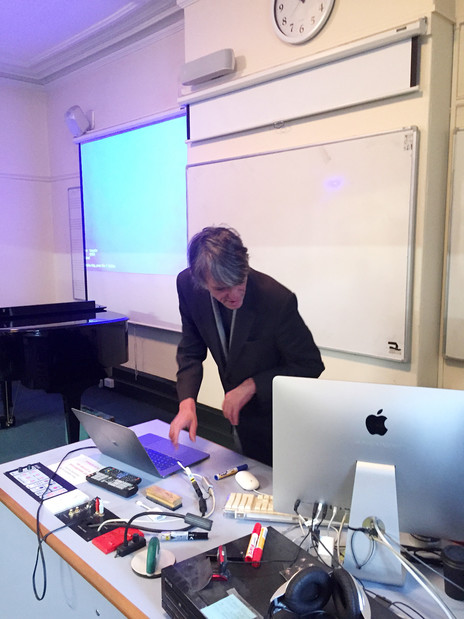

As a senior lecturer – and subsequently HOD – at the University of Otago department of music, theatre and performing arts, Downes shared what he had learned. He introduced courses in composition and musicology, and developed New Zealand’s first degree in rock music.

He also spoke before classical concerts and shared his knowledge on RNZ Concert, and was behind the Tally Ho series in 2015, 2017 and 2019 in his hometown, in which Flying Nun music he orchestrated was played by the Dunedin Symphony Orchestra with guest musicians such as Martin Phillipps of The Chills, Shayne P Carter and David Kilgour.

And for three years from 2018 he was on RNZ National’s Nine to Noon, talking music of all kinds. His deconstruction of Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ through self-similarity was typically insightful, provocative and enjoyable.

Anthonie Tonnon was one of his students, and shared his experience with AudioCulture: “Graeme’s songwriting lectures were legendary, and the highlight of the week for me. He showed us the tiny, tightly wound components in a song that make it work together like a Swiss watch. He found tricks from classical or romantic composers in seemingly simple pop songs – and showed how they underlined the effect of the lyrics. He even had a lecture where he compared Nirvana to Shostakovich. It was like learning the engineering behind miracles, but it wasn’t Penn and Teller – he always remained in awe of a great song. He made many of us devotees of Randy Newman’s 1970s political songwriting, no mean feat considering we grew up with him being the guy from Toy Story.

“Most importantly, he taught us how to learn from other songwriters. I remember him showing us a Bruce Springsteen song that hung around the IV and V chords without ever getting to the tonic, creating a sense of no resolution. He told us it wasn’t a good idea to sing like The Boss, or copy his guitar style, but it was worth playing around withholding that tonic chord to get a feeling across. Graeme was at his best when he took his reverse engineering approach to new music, and in recent years on Nine To Noon it’s been a pleasure to hear him find things that amaze him in Billie Eilish or Lorde’s writing.”

It was on his RNZ radio slot in late 2020 that Downes let it be known it would be his final appearance on air. As we learned subsequently, he has cancer (he hasn’t said what type) but he was typically philosophical and circumspect.

At 58, he took early retirement from the university and moved to Otaki on the Kapiti Coast to be near family. He told the Otago Daily Times, “It’s not flash. Put it this way, I’m not going to be in much of a position to do radio shows for quite some time. “I’m going through various testing options ... and then surgery.”

It was curable, he said. “It is what it is, you just get on with it.”

In 2021 Dr Graeme Downes was made a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to music and music education.