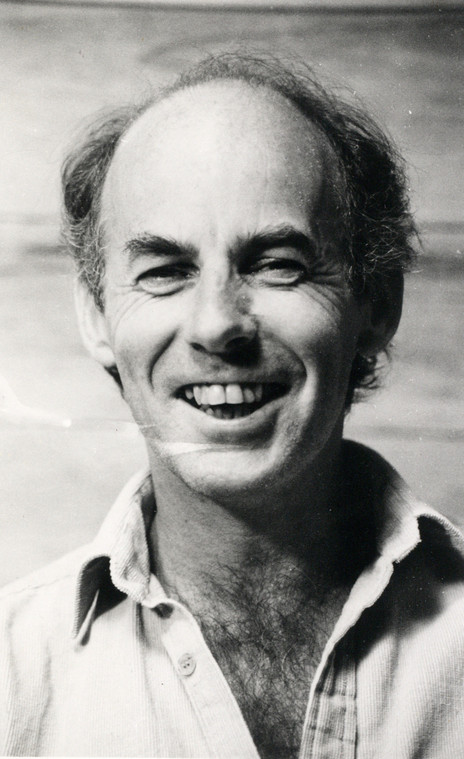

Michael Anthony Nock was born 27 September 1940 in Christchurch although most of his childhood was spent in Ngāruawāhia and Nelson. At around 11 years old Nock began taking piano lessons with his father. After his father’s sudden death in 1952 lessons continued with Ngāruawāhia pharmacist Bert McNamara.

The jazz programme Rhythm on Record, hosted by legendary broadcaster Arthur “Turntable” Pearce on 2YA, was crucial to Nock while growing up. “I used to listen to it as a kid,” he told RNZ in 2024. “He’d say, ‘Any jazz, any blues, any beboppers today?’ That was his call sign. He would play the latest music from the US, it wasn’t all jazz, but it was comprehensive. There were little groups all over New Zealand that would study this show and get together and talk about it.”

Nock’s considerable appetite for music, and a driving ambition to play as well as possible, saw him move to Wellington around 1956.

Leaving school as soon as legally permissible, Nock fell in with some Nelson musicians and began performing jazz and dance music. It was a good place to start but Nock’s considerable appetite for music, and a driving ambition to play as well as possible, saw him move to Wellington around 1956.

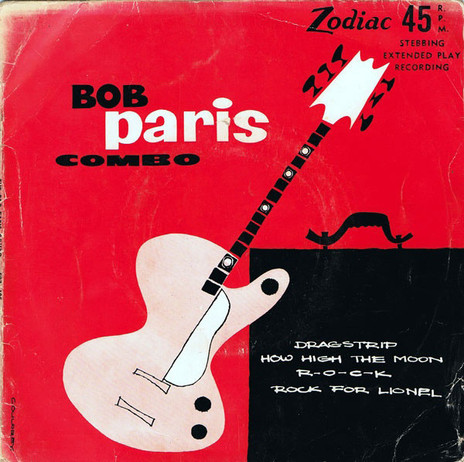

In Wellington Nock played with many local musicians and for a time worked with The Fabulous Flamingos, a Palmerston North-based dance outfit promoted by popular entertainer Johnny Cooper (and Mike played uncredited piano on several recordings by Johnny, not least the classic 'Pie Cart Rock And Roll'). Conditions in that group were so straitened that they had to sleep together in a single room at the motor camp, and to eat, they stole vegetables from gardens or money from milk bottles on the street. Occasionally, a girlfriend might be roped in to help provide some money or food, but the gigs simply didn’t provide enough income to support the band.

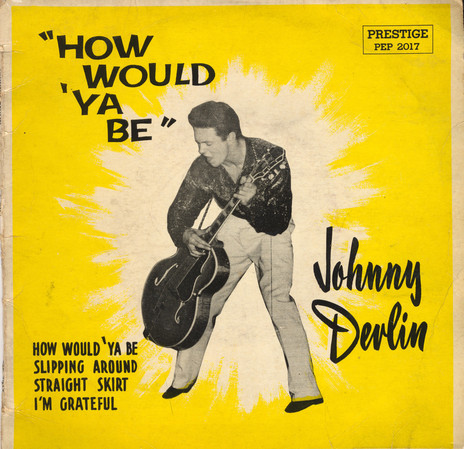

The greener pastures of Auckland inevitably beckoned, and by 1957, Nock was living there. He was soon performing with many of the best players, recording with early rock and roll singer Johnny Devlin, and forming important relationships with drummer Tony Hopkins, trumpeter Kim Paterson and, in particular, drummer Lachie Jamieson. As good as it was to play with Jamieson, who had spent time in the United States working with musicians including Sonny Rollins, Nock’s ambition was to experience first-hand the heartland of jazz, the United States; he believed that the best route there was by way of Australia.

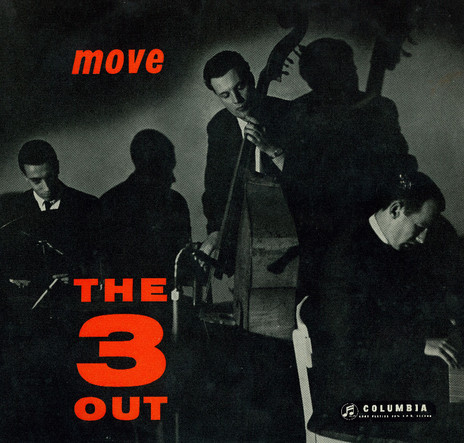

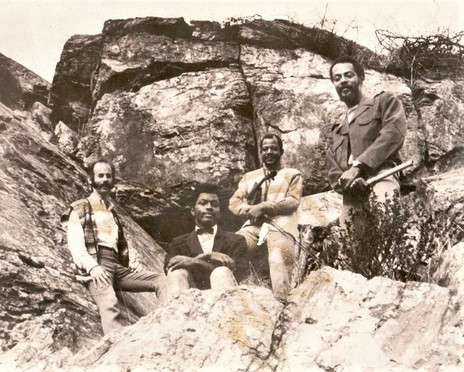

Stowing away on a boat, Nock arrived in Sydney in 1958 and soon became embedded in the local scene. His group, The 3-Out Trio with bassist Freddie Logan and drummer Chris Karan, became one of the most popular jazz groups in Sydney. They played up to four nights a week at King’s Cross jazz club the El Rocco, and recorded Move for EMI’s Columbia label in 1960. The album sold like hotcakes, and its follow-up, Sitting In, featured a number of Australian horn players performing with the trio.

The extraordinary local success Nock enjoyed with The 3-Out was a double-edged sword: while he was grateful for the opportunities to perform and the financial benefits of the group’s high profile, he was also aware that such local acclaim was a trap that might entice him to stay in Australia.

His plan had always been to get to the United States, and to that end, he applied for a scholarship to Berklee College of Music in Boston. News that Nock had been awarded a scholarship to the school saw The 3-Out Trio sail for England, playing for their passage. They spent a few months performing in the UK and Europe before Nock travelled on to Boston and study.

Nock quickly established himself on the local scene, working as house pianist at Lennie’s on the Turnpike, where he played with many jazz luminaries, including Coleman Hawkins, Zoot Sims and Buck Clayton. Some of his most formative experiences during the 1960s included playing with drummer Tony Williams, saxophonist Sam Rivers, and multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef.

Playing with such exploratory musicians fired Nock’s musical imagination and left him with a life-long appetite for music that defies category.

Playing with such exploratory musicians fired Nock’s musical imagination and left him with a lifelong appetite for music that defies category. Lateef invited Nock to join his touring band in 1964, and with the group, the pianist recorded the live albums Live at Pep’s, Volumes 1 and 2, and the studio album 1984.

Lateef introduced the young New Zealander to the African-American sources of jazz and was a profound influence on him. He later said, “I don’t believe you can play this music called jazz without first understanding the roots of the music, which come from black America.” Appearances on Lateef’s recordings during that period propelled Nock to national exposure.

Settling in New York, Nock performed with many of the significant names of the time – Stanley Turrentine, Booker Ervin, Art Blakey, Tony Scott – and enjoyed regular touring work with Dionne Warwick.

Despite good opportunities, making a living as a jazz musician in New York during the 1960s was challenging. Nock recalled: “Life was pretty intense; you had no money, you had very little to eat, and you were getting paid very little for jobs. The pressures were still there, but you didn’t care. You loved it, you played, and that’s all you cared about, playing.”

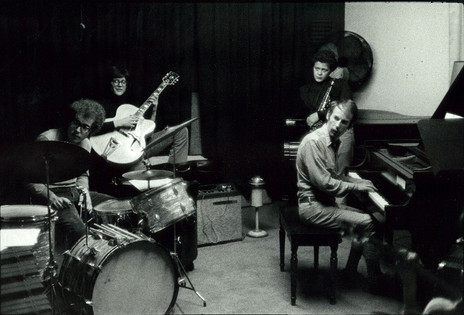

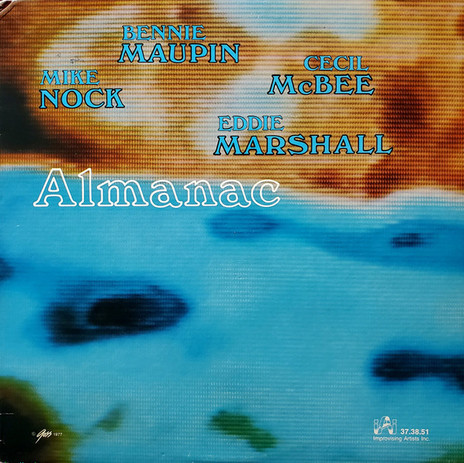

Nock’s own group, a trio with bassist Cecil McBee and drummer Eddie Marshall, recorded Almanac in 1967. Essentially, the pianist’s first album as a leader, it also featured Bennie Maupin on reeds, and when belatedly released in 1977 on pianist Paul Bley's Improvising Artists Inc. label, received a 5-star review in DownBeat magazine.

One of the most exciting musical experiences he had in the city was with Count’s Rock Band, led by saxophonist Steve Marcus and including Larry Coryell on guitar and Bob Moses on drums. As one of the first jazz-rock groups, they recorded two albums for the Vortex label before Nock left the city for the calmer waters of California to perform with saxophonist and Charles Mingus alumnus John Handy.

Handy’s group enjoyed popularity with young rock audiences, and Nock found himself performing in some entirely new contexts, although the experience wasn’t always entirely to his liking. “In San Francisco, we used to work the Fillmore opposite all those big [rock] groups, and man, it was like being on another planet. I couldn’t relate to the loud rock and roll; it was tasteless and corny shit to me.”

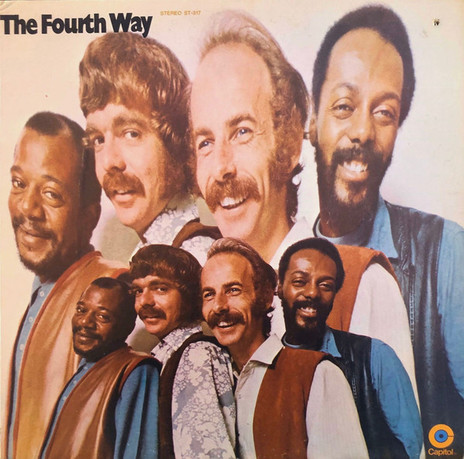

However, there were ideas and approaches from rock that Nock did find inspiring, and within a year of relocating to the West Coast, Nock and violinist Michael White left John Handy’s group to form a new band using some of those musical approaches. That group, The Fourth Way, included drummer Eddie Marshal and bassist Ron McClure, and although relatively short-lived, has been celebrated as one of the first fusion groups, mixing jazz with rock music and playing amplified instruments. They recorded for the rock division of Capitol Records – the Harvest label – and released three albums to critical acclaim.

A high point was performing as the opening act for Miles Davis’s group. The Fourth Way was on fire that night, and Davis found himself upstaged by the young San Francisco group. Miles reportedly said, “Man, I’m never going on second again.”

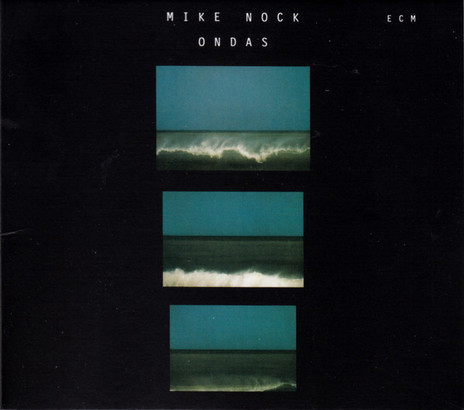

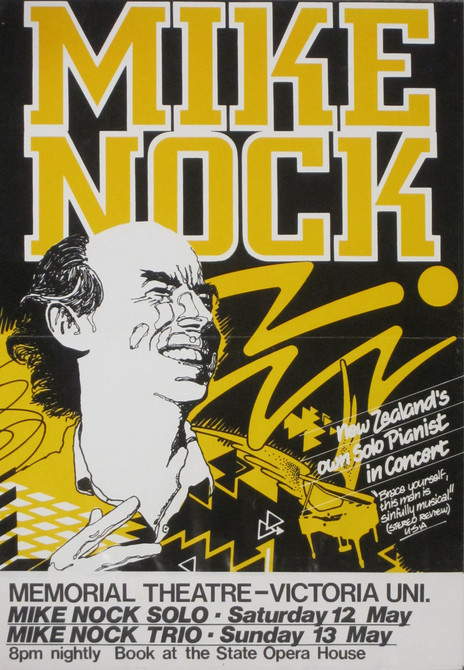

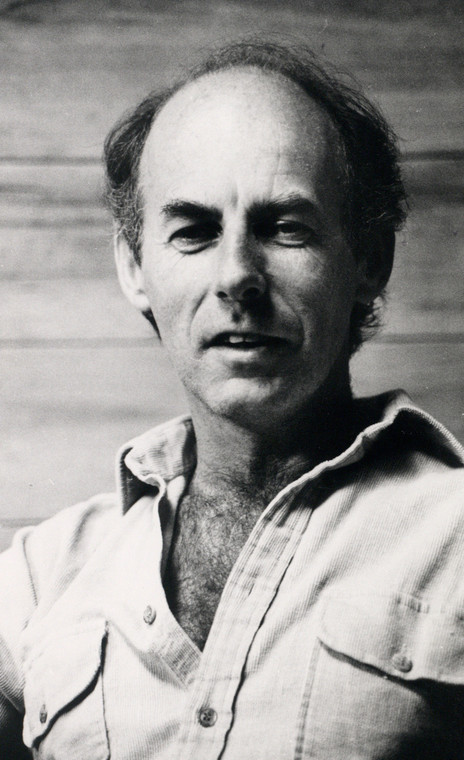

Nock returned to New York in the mid-1970s to reacquaint himself with the scene, and once there, he frequently performed and recorded as a leader. From this period, his albums include Magic Mansions (with Charlie Mariano), In, Out and Around (with Michael Brecker), Climbing (with John Abercrombie and Tom Harrell), Succubus with Alex Foster and two solo albums, Piano Solos and Mike Nock Solo (recorded in Australia). A high-water mark from this period is his trio record Ondas. Including bassist Eddie Gomez and drummer Jon Christensen and recorded in just two hours, the album was released by the ECM record label. It is a beautiful record, with a pristine sound and austere performances. Nock has said, “I am amazed at just how good it is.”

Returning to Australia in the mid-1980s, Nock settled in Sydney, where he began teaching at the Sydney Conservatorium. Since his return, he has balanced a teaching career with composing, regular touring, plenty of recording and a stint as artistic director for the Naxos Jazz label. His recordings with The New York Jazz Collective reveal that life in the Antipodes has done nothing to dull his edge, and his albums with young New Zealand and Australian musicians contain some of his finest writing. Highlights include the quintet album Ozboppin’, his large group recording Meeting of the Waters, and his recent spate of recordings on his own label Fourth Way Music (FWM).

Compositionally, the last 30 years have been very rich and include many compositions for jazz groups, as well as writing for big band and a variety of chamber group pieces. ‘Transformations’, for string quartet and jazz band, and ‘Sketches’ for jazz quintet and chamber orchestra (both recorded and released by Ode) are indicative of his work in this space. He has also written a great deal of fully notated music for solo piano, compositions that have been recorded by Australian virtuosi Michael Kieran Harvey and Simon Tedeschi, plus New Zealander Michael Houstoun.

Nock lives in Sydney with his wife, Yuri, and continues to teach, write and perform. Teaching has become very important to him, and as a seasoned jazz musician who proved himself in the turbulent US scene, he has found there is much to offer aspiring young jazz musicians in Australasia. He takes this role very seriously, both in the classroom and by hiring young players for his groups.

“That has been one of the great joys to me of being in Sydney; that I have been able to take on this role. It’s been wonderful, like a thousand flowers blooming. In the last twenty years, I’ve seen some amazing music being made, and some of the talent that has emerged there is really quite staggering.”

--

In October 2024, Mike Nock was to be inducted into the NZ Music Hall of Fame/Te Whare Taonga Pūoro o Aotearoa.

–

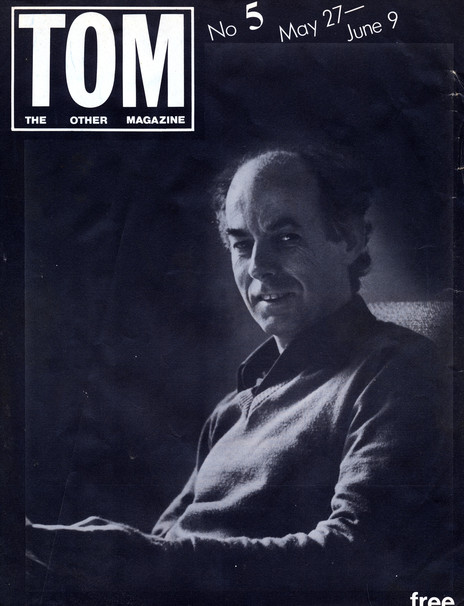

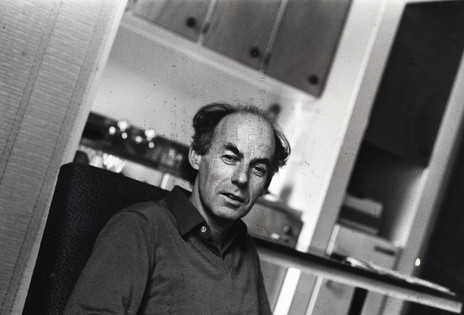

Chris Bourke on Mike Nock, 2010.