Maniapoto spent eight years getting experience singing on the South Auckland club circuit, playing venues such as the Peppermill, Cleopatras and Club 21. This was followed by gigs in Auckland itself, as well as concerts, rallies, union gigs and even gang headquarters, organised by her husband and manager, Willie Jackson. With this apprenticeship, observed Donna Yuzwalk in Rip It Up, “you’re not likely to harbour illusions of instant stardom.”

Her first release as Moana was ‘Kua Makona’, produced by Ryan Monga and Dalvanius, appearing on the latter’s Maui label in 1986. Its lyrics – again in te reo – were about alcohol moderation. In the late 1980s she joined the Wellington band Aotearoa which, led by Ngahiwi Apanui, specialised in original reggae songs sung in te reo.

But, like so many New Zealand musicians before her, it was a cover version that broke Maniapoto through to mainstream airplay. ‘Black Pearl’ was originally a hit in 1969 for biracial US group Checkmates Ltd, produced by Phil Spector, who co-wrote it with Toni Wine. In 1990 Moana and the Moahunters turned the song into a celebration of Māori women as taonga: precious treasures, gifts, living jewels. The message, the press release declared, was “E tu, wahine Māori! You’ve been in the background much too long. All Māori women, kuia, whaea, kōtiro and babies are beautiful and special, whatever their job and role.” Only a few changes were necessary to turn the song into “a good positive song for Māori women”: minor alterations such as “You’re my Miss America” becoming “You’re my Ms Phenomenal”.

‘Black Pearl’ – already a dancefloor magnet at Moahunter gigs – reached No.2 on the New Zealand charts, and was on the charts for 14 weeks. Its message of affirmation for women, Māori and Māoritanga has remained the cornerstone of Maniapoto’s music and public life ever since. But it was a continuation of an approach she had established in the four singles released before ‘Black Pearl’, and in her other lives: as a stroppy talkback host on Aotearoa Radio, as a legal rights advocate.

The follow-up single, ‘AEIOU’ declared her agenda even more directly: the sub-title ‘Akona Te Reo’ means “learn the language”, with the song’s chorus – written by Mina Ripia as a jingle for Aotearoa Radio – cheerfully showing the correct pronunciation of vowel sounds in te reo. Set to a funk backing, with a rap from Teremoana Rapley in the bridge, the song’s message – directed at every race – was “get back to your roots”.

The MOAHUNTERS developed their own approach to soul, in which funk met “haka house music”.

Moana and the Moahunters were a band fronted by a trio; with vocalists Teremoana Rapley and Minia Ripia they developed their own approach to soul, in which funk met what Maniapoto called “haka house music”. Rapley and Ripia were “young, energetic, staunch and cute,” Maniapoto told the Auckland Star’s Tahu Kukutai. “They don’t drink and smoke so I never have to worry about them turning up half-cut to perform. They’re also incredibly loyal and punctual.”

Their sweet harmonies were presented with dance routines, backed by accomplished funk musicians who had come through a similar apprenticeship: Cadzow Cossar, Jay Dee, Ritchie Campbell, Teina Benioni and Peter Hoera. She spoke of them indulging themselves on ‘Black Pearl’, making the song longer, and adding a rap from Upper Hutt Posse, before the genre was widely accepted.

As always, behind the seductive soul was a positive message: female pride and Māori cultural awareness. “We thought Māori music had a lot of international potential because it’s something different,” Maniapoto told Yuzwalk in January 1991, as ‘Black Pearl’ was edging into the Top 20. “We didn’t see much point in just being another funk/soul band with Māori artists because Chaka Khan and co do it heaps better than we do. But they can’t sing in Māori and do the haka.”

Though Maniapoto (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Tuhourangi, Ngāti Pikiao) was born in Invercargill, she went to St Joseph’s Māori Girls’ College in Napier. Her father and mother – respectively, a watersider and factory worker – “slogged their guts out” to send her to boarding school. Though not a native speaker of Māori, visits to the local marae were a key part of her childhood. After her father Nepia had given a speech, he would make her sing. “I was so shy – I hated getting up in front of people,” she told Kukutai. I used to die of embarrassment when Dad made me sing. Then he used to get up with his brothers afterwards and they’d do those doo-woppie sort of songs which were really great.”

In 2014, Maniapoto wrote evocatively for the Sunday Star-Times about her childhood. Nepia would pick up his guitar every half hour. “He came from the era where vocal harmonies were king … He and his four brothers were like the Māori Platters. They’d sing non-stop from the time visitors sat down for a kai at the marae until they finished. They sounded as good as they looked. And totally nailed [Prince Tui Teka’s] ‘E Ipo’ and ‘For The Life Of Me’.

Moana: “Something in Renee Geyer’s smoky voice hinted at life outside the convent.”

St Joseph’s is famous for its choir and its kapa haka training. Maniapoto’s kapa haka mentor was Georgina Kingi, who also tutored Whirimako Black, Hinewehi Mohi and Maisey Rika. After hours, the music of Renee Geyer ruled among her classmates. “Something in that smoky voice hinted at life outside the convent. I learnt to play ‘Heading in the Right Direction’ on guitar. Just as well. It was a classic Māori party song.”

Parliament’s ‘Flashlight’ “blew my socks off”, she said, as well as Chaka Khan. But pivotal was the moment she and a friend hitch-hiked up from Hamilton, in their first year of university, to see Bob Marley at Western Springs in 1979. “We were 17 years old: wide-eyed, ex-convent girls and Bob Marley was our first ever rock concert. Life-changing stuff.”

While studying law at University of Auckland, Maniapoto’s world combined rallies and protest marches – and debriefings at the legendary Kiwi Tavern on Symonds Street – with a social life that recalled her childhood. “We hit the clubs, where I would often be moonlighting as a singer, then half the club would hit our garage for a party: three guitars, plenty of Bob, Renee and Tui. Set me up for life, I reckon.”

At university, Maniapoto became politically aware – and even more so after she married into the Jackson family – and found her musical footing “at a time when pop, soul, reggae, rap and waiata were all part of the contract,” wrote Graham Reid in the liner notes of the Moana and the Tribe compilation. “Moana’s music has drawn from American soul, taonga pūoro (traditional Māori instruments), female empowerment, tino rangatiratanga (Māori self-determination), hip-hop and contemporary dub. And from waiata and a deep well of intuitive spirituality.

“She’s the only musician I know who could present an album (Rua in 1998) which dealt with Māori grievances and prophecy, love of the land and ancestors, and end with a moving version of ‘Awe Maria’ accompanied by Māori girls from the Catholic school choir she was once part of.”

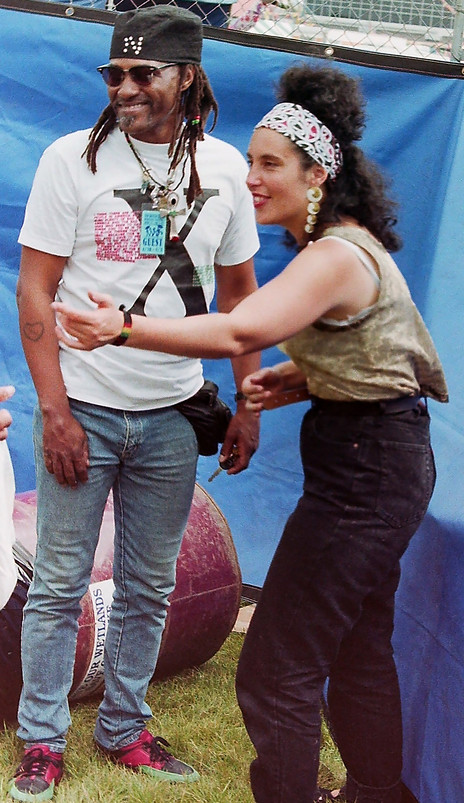

‘Black Pearl’ and ‘AEIOU’ appeared on Murray Cammick’s newly formed Southside label. Shortly afterwards, the Moahunters’ profile was lifted when they were the support act on the Neville Brothers’ first visit to New Zealand in 1991. After taking the politically conscious New Orleans group to Ngā Whare Waatea (Mangere), a rapport was established. The Nevilles featured a snippet of both groups – and everyone else present at the marae – singing ‘Whakaaria Mai’ (‘How Great Thou Art’) at the pōwhiri on their 1992 album Family Groove. It also led to the Moahunters performing at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival that year, alongside other contemporary indigenous groups.

Southside released the Moahunters’ first album, Tahi, in 1993. William Dart described it as “a mighty debut, fearless in its diversity, and the risks it takes.” Already the elements of Maniapoto’s music and vision were present. It featured acclaimed te reo songwriter Hirini Melbourne’s ‘Tihore Mai’ performed a cappella by the trio, with a backing of traditional instruments: poi, karanga weka and hue. The video of ‘Peace, Love & Family’ included vintage photographs of warriors and kuia. Maniapoto found the production so powerful that at the editing session she had a minister give a karakia before they began.

There was a sense of history throughout the 1993 album ‘Tahi’.

There was a sense of history throughout the album, especially on ‘Back Where We Belong’, an archetypal Maniapoto fusion of soul, gospel and karanga, accompanied by an acoustic piano; the song was co-written with Minister Rasul Muhammad. Tahi led to an association with Melbourne’s cohort in Māori instruments, Richard Nunns, and began a collaboration with Ruia Aperahama.

But there were also tracks aimed at airplay: the sweet soul ballad ‘Seven Years’ (produced by Simon Lynch), a sensitive cover version of Jimmy Cliff’s ‘Rebel in Me’, ‘Sensual’, with a muted trumpet from Greg Johnson, and a wordy duet with Andrew Fagan on his ‘I’ll Be the One’. The pop-rock song was aimed, said Maniapoto, at “white male parliamentarian types. As the song says, you can tuck your tie between your legs and bugger off, basically.” The album’s title track ‘Tahi’ was a tour de force, six months in the making and presented twice: a Māori roots version based on a two-verse moteatea by Hareruia Aperahama, and a bilingual dance mix co-written with Angus McNaughton, fresh from his successes with the Headless Chickens. The 12” single also featured an eight-minute audio documentary on traditional instruments. The video starred kapa haka icons Waka Huia.

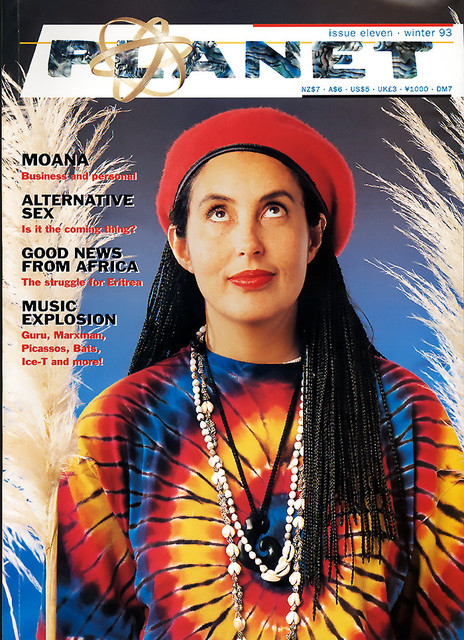

Maniapoto credits Jackson, her former husband, manager, and strategist, with a lot of her momentum in her early career. With national tours and television appearances, her profile was so high in 1993 – she had already had a stint hosting TV3’s Yahoo show on Saturday mornings – that she was invited to play a doctor on Shortland Street. Within a year, Tahi sold more than 8000 copies.

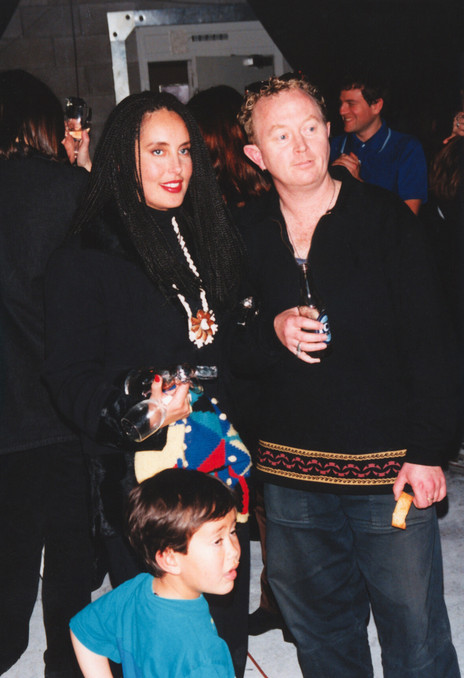

The Moahunters gained more international experience through the Womad circuit, but in 1998 after a tour of Canada the trio was dissolved, and the Maniapoto-Jackson marriage had come to an end.

In 2001, Maniapoto performed a series of acoustic concerts in Florence accompanied by Cossar, Richard Nunns, Warena Morgan and Hereana Roberts (two top haka performers). A year later, she was approached by German manager/agent Sol de Sully. They established a new group: Moana and the Tribe. They released the album Toru under the name Moana in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Italy through Pirate/Sony. “It was sweet-as with the Italians because I shared my name with the most famous porn star in Italy,” she joked to Trevor Reekie. But a German media company has the trademark for the word Moana and threatened Pirate Records with a law suit. So, while driving down an autobahn, the group hurriedly came up with Moana and the Tribe: “the best out of a really stink bunch of names we came up with under pressure.”

The Tribe she describes as "a fluid group of talented performers": more than three dozen are listed on her website, including Cadzow Cossar from the Moahunters band, Paddy Free, and bassist Max Stowers. Maniapoto's husband, filmmaker Toby Mills, is tour manager and handles the multi-media effects.

Since Tahi there have been four more albums, continuing the te reo numbering: Rua (1999, on Tangata) with the Moahunters. With the Tribe, Toru (2002, Tangata), Wha (2008, Black Pearl/Ode), and Rima (2014, Rhythmethod/DRM). A Live Unplugged album was released in 2005, the Best of compilation in 2012 on Black Pearl/Ode, and in 2003 the Live & Proud DVD (on Pirate in Europe, King in New Zealand).

There would be few New Zealand artists who have taken their music as many places as Maniapoto. With her bands she has toured the Pacific, Europe – especially the festival circuit – and even Russia. “In fact,” Reid points out, “Moana and her groups have performed more often outside Aotearoa than within it, and that has been our loss. And shamefully, her uniquely New Zealand music is rarely played on local mainstream radio, because it is in te reo or doesn’t fit the format. That has meant her career has often mean a struggle.”

From the beginning, Maniapoto has been a champion of Māori music of all kinds, for radio acceptance and also for acknowledgement at national awards. It is partly through her efforts that Māori music has more of a profile at the annual New Zealand music awards – at which Māori felt marginalised for many years – and the establishment of the APRA Maioha award. In 2004 she was made a New Zealand Order of Merit for services to Māori and music, she received the Tohu Mahi Hou a Waka Toi award in 2005 (for leadership and contribution to Maāori art), and in 2007 became an Arts Laureate. She is a Toi Iho accredited artist and trustee. In 2016 she was inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame.

From the beginning, Moana Maniapoto has been a champion of Māori music of all kinds.

In a 2016 essay, ‘Mana Wahine: Māori Women in Music’ in Te Kaharoa, Maree Sheehan wrote, ‘Maniapoto’s mana as a Māori woman is not limited to receiving recognition and accolades outside her community. Her mana is grounded in her whakapapa, her connection to the whenua and the relationships she upholds in her iwi, hapū and whānau. Throughout her music career she has remained true to composing and performing kaupapa-driven waiata that are also expressions of being Mana Wahine.”

The same year, music journalist Graham Reid asked Maniapoto whether, after all these achievements, she had any unrealised goals. An international No.1 hit that “could only have come from New Zealand” was just one of the answers.

In April 2019 Moana and the Moahunters’ 1993 album Tahi was revealed as the recipient of the Independent Music NZ classic record award at the Taite Music Prize. The award acknowledges music that has inspired and influenced others, long after its release.

--

Watch: Moana Maniapoto interviewed by Ross Cunningham for AudioCulture.

Read: Moana and the Tribe.

Read: Brothers and Sisters, 1992 – Moana and the Moahunters in New Orleans.