New Zealand had a thriving folk music scene in the 1960s. In 1963 the Kiwi record label began releasing albums by New Zealand folk artists, Wellington channel WNTV began a local folk programme in 1964, and LPs by American folk singers enjoyed strong sales. Also in 1964, in Auckland, a group of enthusiasts began promoting Sunday night concerts and University Arts Festival shows. In October a five-day folk-singing festival was held around the city’s art galleries and at the Town Hall Concert Chamber (where critics felt that the ratio of good to indifferent performances was about one to three!). The Auckland University Folk Music Club was formed and 500 students attended their 1965 orientation concert. Peter, Paul and Mary toured nationally, and Nina and Frederick performed at the Auckland Festival. The Anglican Youth Movement held a hootenanny at St Mary's Cathedral.

This activity continued right through the 1960s: in Durham Street in the central city, the Blind Lemon Folk Music Club opened, across the harbour bridge the Devonport Folk Club was formed, and in 1967 the Poles Apart folk club opened in Newmarket and the Rafters Folk Club on Ponsonby Road. By 1967 the Northern Federation of Folk Clubs had been created, and weekend evenings at the Wynyard Tavern were jumping. Also that year the first of four National Banjo Pickers Conventions were held at Hamilton.

Roger Giles was born on 7 April 1941 in Devizes, a market town in Wiltshire, England, around 25 km north of Stonehenge. His father George Giles was publican of a small pub in nearby Childrey called The Crown; behind the bar was Emily Cleverly, a former nurse who became his wife. Roger was an “afterthought” – his father described him as “bomb damage!”. His older brother Robert and sister Janet were, respectively, 13 and 10 when he was born.

As a boy Roger wanted to be a shepherd, so he could spit accurately into the fireplace.

So Roger spent a lot of time hanging round the pub and annoying the local characters. The shepherds would come into the pub for lunch, drinking pints before the fire. By the age of five he decided he wanted to be a shepherd, so he could spit accurately into the fireplace and whistle the dogs and tend the lambs. In the evenings, Janet played jazz piano in the lounge bar for visiting US servicemen.

Childrey (pop. 300) is about 4 kms from the Uffington White Horse earth sculpture on the northern edge of the Berkshire Downs; the rolling chalk land was planted in wheat and barley during World War Two. Before that it was watercress, racing horses and sheep-rearing country. Roger did well at the Childrey Community School but intentionally failed his 11-plus exam so that he could become a shepherd.

But this was not to be. George’s family were potters and brick-makers in Devizes and when Roger’s Uncle Bert died George was asked to manage the brick yard, originally set up in 1800 to build the walls of the Caen Hill Locks on the nearby canal. The pubs were sold and the family moved to Devizes when Roger was 14, and he continued at Southbroom Secondary School until he left at 15 for a job on a dairy farm.

Milking cows for a living turned out to be drudgery so Roger took night classes, winning a scholarship to study for a diploma in agriculture. After working as a stockman on a Hereford experimental farm for two years he headed north to Culmington, Shropshire, becoming head stockman for a family that owned several farms fattening sheep and cattle.

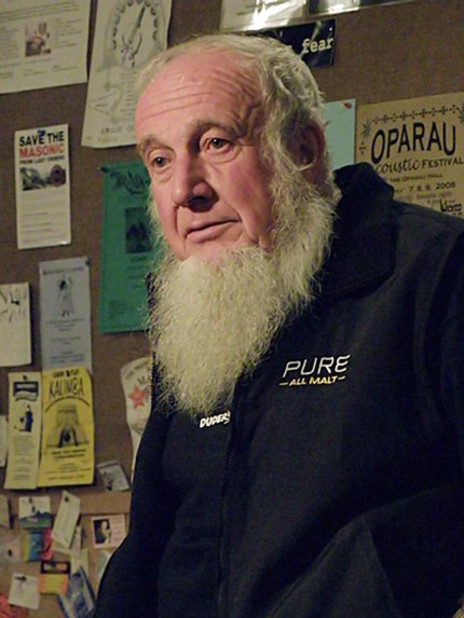

For five years he lived at the Royal Oak Pub, and around this time he began sporting his trademark Old Dutch beard.

In the pubs run by his father, the locals used to turn up on the weekends with their squeeze boxes and violins to sing the local ballads and love songs, which Roger soaked up like a sponge. The Royal Oak was run by Jan Jordan, whose uncle Fred was a popular traditional singer performing at folk clubs and festivals throughout England. Fred and the locals often used to sit around the fire at night and sing, Roger recalled: “I learnt to play the double bass badly, mainly when the bass man with the local trad jazz group got too drunk or forgot to turn up.”

“I learnt to play the double bass badly, mainly when the bass man with the local trad jazz group got too drunk.”

In 1963 champion New Zealand shearer Godfrey Bowen visited the UK to demonstrate his new pressure-point technique and Roger – who had learnt to shear using the cumbersome English system – was impressed. He envisioned a lifestyle of making a fortune during the summer and wintering over in Spain. Being born with a curvature of the spine which doctors had been unable to straighten was an advantage, said Roger: “as a humpback I was well suited to being a shearer. I was already half-way bent over to start with! When I was young I had to wear a corset and slept on a plank.”

He saw an advertisement in the Farmer’s Weekly for farm workers to travel to New Zealand and he applied. In 1965 he boarded the SS Southern Cross for an assisted passage to Wellington. “It was an experience for me; I’d never been out of England before, the booze was duty free and I was in heaven!” He took the overnight train to Hamilton and studied at the Te Aroha Dairy Company factory. His ute arrived from England and he was given a round in the Rotorua district for a season. As a herd tester he spent each night on a farm and tested their herd for butter fat.

Roger then bought himself out of his contract and went shearing, but that didn’t work out as planned. “When you're not shearing you’re drinking. I’d made a fortune and I’d spent a fortune on drink and eventually I realised that I couldn’t go on doing this!”

He moved to Devonport and began a succession of jobs: as a storeman at Arthur Yates, a seagull on the wharves, a porter/trainee auctioneer at Radley’s, and finally with the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries as a quarantine inspector. His job was to inspect containers and cargo coming off the ships for diseases and pests. He collected samples for testing. Later he moved to the airport, checking cut flowers, plant material, fruit and vegetables and tourist souvenirs.

“I wanted to retire when I was 65 but they couldn’t find anyone to replace me. They’d give me these university kids to train up and they would leave after three months because they want to be scientists and all we were was inspectors. So in 2005 I went part-time and three years later a guy at Air New Zealand retired and died that evening. So that was it, I left then and there and I’ve been busy ever since.”

In 1966 Roger met Sonja, a school teacher who at the time was secretary of the Devonport Folk Club. Roger headed back to Britain in 1969 with a plan to find a job with a house and call her over but she became pregnant so he returned to marry her. He realised he preferred life in the colonies. In 1975, when their son Samuel was five, they heard that Roger's father was unwell and expected to die, so the family moved to England. This time Roger found a job in a carton-making factory where he scored a good paying job as the head hoist driver. They bought a campervan and headed to a folk festival in Devon – only to wake up one day to the realisation they could not afford the petrol money home. He found a job on a nearby dairy farm and they lived in the campervan until a worker’s cottage was built. A year later they moved again, to help his brother run a firewood business.

In 1979 his father died and the family returned to Auckland where Roger was lucky enough to get his old job back at the airport. Daughter Emily was born in 1983, but 12 years later the couple separated, with Roger gaining equal custody on the weekends. “The kids have done really well. Sam plays jazz bass, notably in the Chris Mason-Battley Group and Kingsley Melhuish’s Spargo: and Emily plays cello in a bluegrass-style band. She has two kids, Nina and Selma.”

Hilary Condon became his dedicated partner in the Devonport folk music club.

In 1997 Roger became the partner of Hilary Condon, and stepfather to her two boys Kerrin and Alec. Hilary also became his dedicated partner in the Devonport folk music club, handling much of the behind the scenes work and organisation.

When Roger first arrived in Auckland, he could only find a few jazz venues. “It was six o’clock closing so I used to go to the Montmartre on a Friday late night but that was about it.” Eventually he immersed himself in the Devonport Folk Club which at that time was in the basement of the old Devonport Methodist Church, and run by Scotsman John Sutherland. “I didn't like going there at first because all the singers were doing American tunes which I didn’t know. It was only later that somebody told me that the stuff I had heard as a child was also traditional music and suddenly I had a repertoire.”

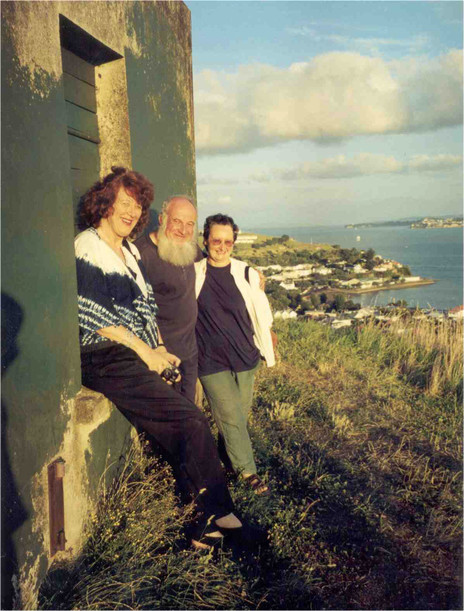

In 1970 Ted Jackson, mayor of Devonport, offered them the use of the old bunker on Mt Victoria. “I was dead against going up there. I told them, that won’t work. Nobody is going to go up the mountain in the winter, in the rain. We need to be down close to the ferry!”

But the club moved in and opened in April 1971; it has been there ever since. The bunker was originally built in 1899 to defend Auckland against a looming Russian invasion. A shipload of faulty railway lines was used for reinforcing, and disappearing cannons installed. During the Second World War it was used as a lookout and fire-command post.

“When we first got there, there were cattle roaming the mountain. They were starving in the winter, damaging the Māori sites and shitting everywhere. I tried to get the council to terminate the lease but in the end I wrote to the North Shore Times. We formed a Friends of the Mountain group and organised fire breaks to be put in and planted trees. We watered them every two weeks during summer and quite a few grew. I still look after the mountain, pulling weeds out and picking up rubbish.”

When the Devonport folk club started at the bunker, there were still cattle roaming Mt Victoria.

Roger was president of the Devonport Folk Club when he left to visit his father in the UK in 1975, and took up the role again when he returned four years later. He would remain president until his death in 2020.

The first Auckland Folk Festival took place in 1973 at Moller’s Farm in Oratia and by the time Roger had returned it had moved to the Knock Na Gree Camp in Oratia, then onto the Kumeu Showgrounds. The festival became a long-standing feature on the folk calendar, celebrating its 40th anniversary in 2013. Roger was MC and on the committee since his return in 1979, but in the late 2010s pulled back from the roles: he felt it was time to encourage younger people to take over. (The festival committee is represented by the Devonport Folk Club, the Bluegrass Club, Titirangi Folk Club, City of Auckland Morris Dancers, and the Gaidhealtachd community from Whangarei Heads.)

Roger Giles died on 14 March 2020, aged 78, after a short illness with cancer. In 2010 the Variety Artists Club of New Zealand granted him its Unsung Hero Award. But to many, not just the folk community, he was an unsung hero. To all who knew him, the great kauri of Takarunga – Mt Victoria – had fallen.