In 1986, when I tracked Malcolm Hayman down to his home in the stark, windswept Wellington suburbia of Karori, this seminal figure of New Zealand music seemed to have been all but forgotten.

For me, it was a personal pilgrimage to meet and interview one of my New Zealand music heroes. Unable to muster any interest from local media in a story about some past-it rocker filling in his last days in the ignominiously titled pub-rock band Captain Custard, I met Hayman under the pretext of a piece I was writing about the evolution of the music scene in the Capital city.

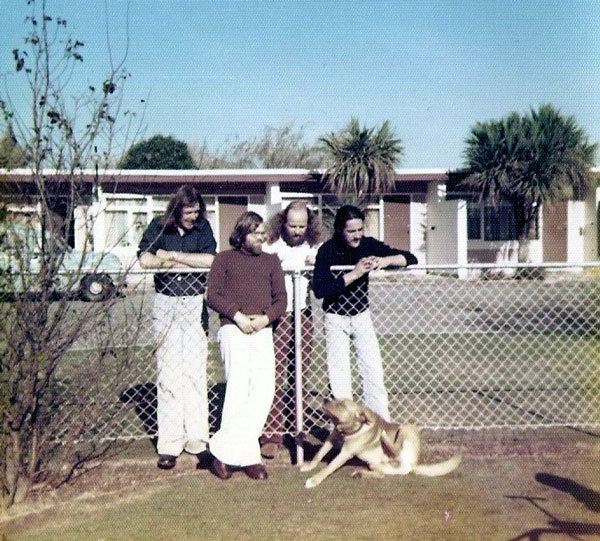

Malcolm Hayman's post Quincy Conserve band Captain Custard, taken about 1981. Left to right: Malcolm Hayman, Peter Whyte, Stu Petrie and Jimmy Dwan - Jackie Matthews collection

It was a profoundly depressing experience. Hayman’s doom-laden, chilly home seemed stripped of all but the bare essentials, and the man whose distinctive voice had wrapped itself around unforgettable songs like ‘Aire Of Good Feeling’, ‘Ride The Rain’ and ‘Alright In The City’ was attached to a catheter, and clearly not well.

Still, the famously abrasive singer, bandleader and arranger proved sporadically effusive and – despite displaying some bitterness and regret – did his best to conjure up memories of a scene that he had helped to shape, but which had ultimately betrayed him. Hayman died just two years later of complications from diabetes, a veteran of the New Zealand music scene at 48 years of age.

“It’s 30 years I’ve been playing professionally this year,” he told me. “That’s a long time to be doing that. I started back in 1956 when I got booted out of school at 15. When I started there were just two dance halls in Wellington, and the hotels closed at six. We used to do one of those dance halls every week. Then I went to Australia for five or six years, came back and formed Quincy.”

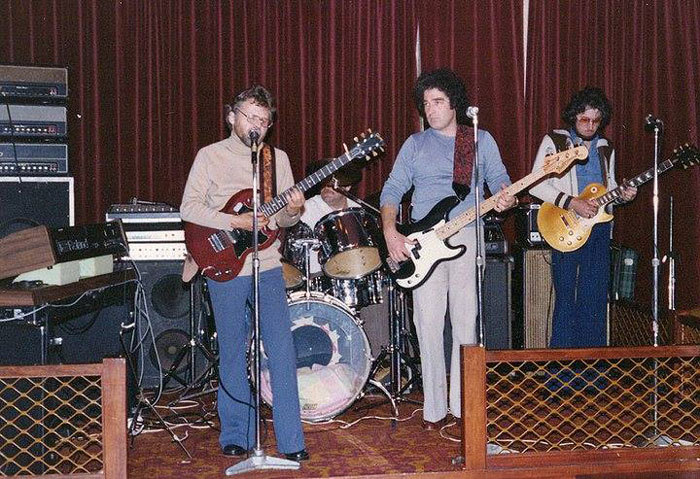

Captain Custard's first lineup in the late 1970s: Murray Loveridge, Malcolm Hayman, Dave Alexander and Don Burke - Murray Loveridge collection

Ah, Quincy. As a school kid in the early 70s, The Quincy Conserve was to prove a revelation. With no real sense of there being a local music scene past the poptastic inanities of television’s C’mon and Happen Inn, and no real rock media, I relied on Playdate magazine to find out about the slightly more "underground", credible rock bands, and that’s where I first heard of "The Quincies". When I got hold of their records, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. What we heard and saw on radio and television in those days were the predigested, manufactured singers: people like Mr Lee Grant and Craig Scott. Real rock bands were "underground", and the best way to hear them was at some live event. Quincy Conserve were something else again: I didn’t know what to call it back then, but their music was heavily jazz accented and laced with funk, soul and rhythm and blues influences, with a dash of psychedelia and progressive rock around the edges. They were also easily the tightest ensemble I had ever heard, and the first time I had heard a properly arranged horn section in a rock band. That made for a powerful mix.

Quotes

Hayman on Mr Lee Grant

"I made most of his records for him. He had a manager, Diane Cadwallader, and she got him everywhere. That lady was devoted. And she was smart too. She was a business lady – she had a couple of boutiques. But she decided that he was going to be the next star. She taught him how to stand, how to move and sing, and he didn’t do that real well. I can remember cutting a track called ‘Maria’. I did that thing for him. And we had half the National Orchestra in the studio and he had to put the voice down coz it’s ad lib. And we were there from 9 o’clock in the morning to half past four in the afternoon, and he still didn’t get it done. He couldn’t sing in tune … And I was thinking these string players were worn out – they couldn’t even vibrato in the end. We were stopping for numerous cups of coffee and swearing sessions in the toilet. And this guy was trying to sing. But he was a good act. He looked good. He had the legs and the height. He used to have the suits at the arms ripped off and the girls used to grab the arms, and the arms would come away – it was all set up, she would have these girls to run up onstage, grab the suit and tear at him and they’re pull them off by the hair. But this guy standing in the middle of the studio looked like a lump of jelly. We got it down in the end, but it’s the most atrocious version of ‘Maria’ you’ve ever heard in your life.”

Hayman on Split Enz

"I played their first gig with them actually – in the Christchurch Town Hall. I remember thinking ‘this band will never go anywhere!’ They were the opening act. They had amateurish equipment. And they had this tape, and they put this tape thing down, connected it up before we started, and then they came on with all the lights off y’see. The intro part was on tape. But someone inadvertently tripped over the tape recorder. There was a crash and a thud and the tape went NRRRGH!!! And stopped. Pitch black. Oh no, this is it, but they go on and there were things squealing and whistling and carrying on. And finally they started to play, minus some bass, coz the bass player disappeared off the stage looking for a lead. I felt so sorry for them. They had it so well planned. ‘All the way from Auckland, Split Enz… whistle, scream, burp! That was my introduction to Split Enz. But I tell you what, they were an amazing group when I saw them the last couple of times. They certainly fought their way up from the bottom. Boy did they start at the bottom!"

On surviving in New Zealand music

“I don’t think a lot of people really give New Zealand musicians the credit that is due. We’ve got such a small population that every band in this country’s got to please somebody sometime or they don’t get anything, whereas in Australia you can specialise. You only need a little section of Sydney to like you and you’ve got enough people to follow you and keep you employed, whereas if you have a small section of Wellington you have two people every night.”

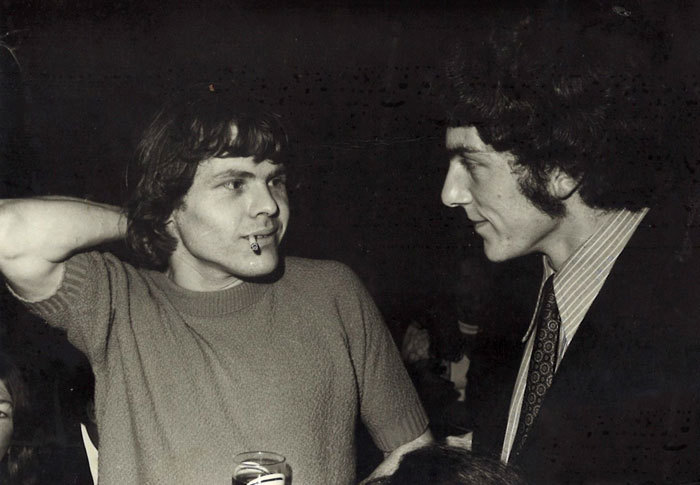

Malcolm Hayman and Raice McLeod, circa 1968 - Jackie Matthews collection

–

Read more: The Jackie Matthews photo collection – Malcolm Hayman and the downtown scene 1956-1975