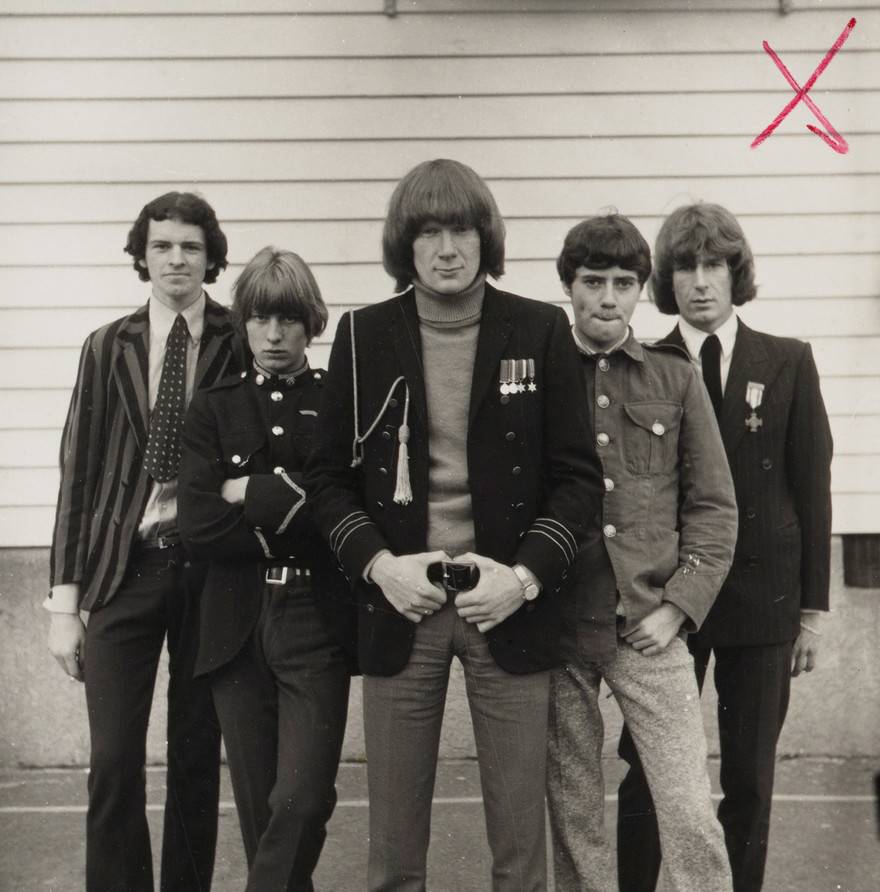

Tom Thumb (Rick White, centre), Wellington, June 1967. - Barry Clothier, PAColl-7031-1-59, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Catching the bug

Rick White: “A typical story. I was straight out of high school art classes. Surf music was around. There was Bobby Darin and those guys. A lot of good mates were into surfie music and had surfie hair, cool looking guys and I was a nerd and then all of a sudden came sixties music – early Beatles, then The Rolling Stones started to happen and ‘Not Fade Away’ was on the radio. I started playing lead guitar in The Electrons because I didn’t know any chords.”

(The Electrons were White’s high school band with Hofner violin bass playing Onny Parun who was soon to be a well-known international tennis pro.)

The anti-career

“Young people played music to get ahead. Kids’ bedrooms were plastered with pictures of pop stars in those days. It was a career alternative and your parents hated it therefore you liked it. I was bought up on ZB stations. My old man listened to Bing Crosby. The Stones played on that – the more the olds hated it, the more you were driven to it. My parents were really worried about me until we got on television (as Tom Thumb). That was a mark of respectability. The only benchmark they had to go on.”

Flirting with the real world

“The economy was coming right. There was more money around and no such thing as unemployment. I had maybe a dozen jobs when I was playing. You’d just tell them to get stuffed and walk out and get another job next week if you wanted one. My first job was working in an advertising agency – KBR – it was the growth industry in those days like computers these days. It was maybe a little alternative. You could get away with wearing a brown suit, not a grey suit and Cuban heel boots.

“I met another Cuban boot wearer there – Dave Jenkinson – who knew a guitarist, Milton Parker, so we started rehearsing, playing R&B and calling ourselves The Relics. We got to know The Breakaways quite well from going to see them play. They said they knew this guy in Wanganui, who was really cool, Alan Beamsley. He looked like Brian Jones. He had the hair. He moved down and became our lead singer.”

Stepping out with The Relics

“The Relics were semi-professional, pretty rough musically, but the stuff we were listening to was rough. We started doing local dances, church dances and rugby clubs. Played all over. Wellington’s suburbs all had their own youth clubs. Wellington had 20 to 30 youth clubs each with their own followings and bands.

Hanky Panky with The Relics.

“We were sharing a flat in Moxham Avenue in Haitaitai. Milton and I had one bedroom. Dave had his own room. Beamsley had the sun room. We’d steal milk bottle money and break into the flat next door and steal their food. The place was like a flophouse. There’d be no money from gigs. The whole lifestyle felt naughty because it was different. When I was just 17 I was going to bible class and had cuffs on my trousers. One year later, I was running around with my dick in one hand, and a bottle in the other, gone totally wild.

“Our only single – ‘Hanky Panky’ backed with ‘Jambalaya’ – was awful. We wouldn’t have chosen to do either song. It was not the sort of stuff we were playing. It was recorded in 1966 at Victoria Street by Viking Records’ Frank Douglas, who chose the songs.”

Exit Rick, enter Barry Coburn

“The Relics rebelled against me apparently. I was a bit of a hard bastard in those days. They brought a guy up from Christchurch to play organ called Barry Coburn. He later left and ended up staying with me before returning to Christchurch.”

(Barry Coburn, was a Viking Records rep who recorded The Unknown Blues and managed Split Enz in their early days.)

Long hair

“We were living a counter-culture existence. We had long hair and were called poofs, louts and queers. There might have been a half a dozen of us in Wellington who had hair over their collars. When I’d just left high school guys I was working with used to offer me two and six to get a haircut. I went to work with my hair brushed back just over my collar, but come five o’clock, I’d shake it down.”

The birth of Tom Thumb

“I put an ad in the paper and got lots of replies – Sammy Shaw was a drummer who’d not long ago arrived from Ireland.”

Didn’t he claim to have played in Them?

“It wouldn’t surprise me if he had. He knew so much about them. He came from exactly the same place as Them. I’ve seen an early photo of Them and this guy could have been Sammy. The name Tom Thumb was from a band Sammy knew in Ireland called Tom Thumb and The Four Fingers.

“I wanted to get Blake Thompson to play guitar. He said 'try my younger brother Graeme'. He turned out to be a really good player, he was later in Quincy Conserve.

“We got a keyboard player Warren Willis, who was a biker and had a leather jacket, greasy hair with a greased down cowlick in front. A real bad dresser. We made him change his image. Paul Newton (the first of many bass players) said he’d done sessions with The Who. I doubt that, but we traded on the fact, we had overseas connections. There was a Union Jack on the bass drum.”

You had a lot of trouble with bass players?

“We chewed through bass players. We were working frequently at this stage.”

Dave Orams (ex Breakaways), Dave Chappell, Mark Tretheway?

“Mark Tretheway was a total manic madman, no drugs, but he used to drink and drink and drink. He functioned, but he was uncontrollable. He’d left us by the time he died. We were playing The Place and someone came in and told us he was dead.”

It sounds like you’re playing lead bass on some of the records?

“The best musical move I made was to go onto bass. On later recordings, whatever I played on, the bass was fairly prominent.”

Revenge

“The first gig we did was a jamboree in Lower Hutt in front of 3,000. We were a little slicker and harder edged than The Relics and it went okay. The English and Irish guys had been through it before and were a bit more pro. There was a stage in one corner – that was us – and in the other corner was the remnants of The Relics (now called The Suburban Mudd). I was blessed; it was our first gig and their last.”

The La Gloria era

“Producer Howard Gable came into a club we were playing one day. All the labels were hunting for pop acts as the pop market was still going strong. Previously La Gloria were doing Maori recordings and poems. A very conservative label. We were their first electric band.

“Gable chose our first two sides. You’d go in and the producer would say, okay guys, play a bunch of stuff that you like, play 10 or 15 songs. It would do two things, get you used to the studio and let him see if you had anything. Nine times out of ten, he’d say, sorry, don’t like any of your songs, you’re bullshit, but you can do this one. We never made any money from the recordings. To this day EMI would have me believe I have no rights to that material.”

The first single: ‘Midnight Snack’ – it was done originally by The Midnite Zoo.

“I didn’t know that. I can’t remember ever being played the original version. We never played it live, ever, but you did it because it might advance you and these guys were supposed to know.”

‘Respect’

“If I ever regret doing a song, it’s that one. It was a few years until I heard Aretha’s ‘Respect’ and realised what I’d done. Our version was horrible.”

The second single: ‘I Need You’ – It’s pretty aggressive. It’s a rip-off of a Pretty Things thing isn’t it?”

“R&B. It came from that sort of thing – Downliners Sect and Pretty Things. I can’t remember writing it. We played it live. If nothing else, it’s nasty.”

What’s it about?

“When you weren’t working, you’d hang out together. The guys you were working with are closer than anyone else, even your family. Because you relied on them 100 per cent and had a common goal and ambition. You relied on each other until you split, then you were incredibly unclose, like a marriage really.”

‘Got Love (If You Want It)’ – it’s on the first Kinks and Yardbirds albums.

“We used to play it at 20 times the speed live. Anything Sammy’s playing on, that got recorded, you can guarantee it’s faster than the original.”

It was supposed to have been banned by the New Zealand Broadcasting Commission?

“I remember nothing about it being banned.”

The third single: ‘Whatcha Gonna Do About It’?

“If you listen to the early stuff we recorded it’s a 17-year-old's voice and it’s pretty squeaky. I wanted a voice with a croak in it, bearing in mind, I was listening to guys like Steve Marriot (it’s a Small Faces song) and Eric Burdon and those guys made their voices croak. So I had a hot shower, started running up and down in the dead of night, naked, trying to catch cold and get that croak in my voice.”

‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’ – the original is by The Thirteenth Floor Elevators, a Texas band. It was a minor hit in the United States.

“It’s not the kind of thing Gable would have handed us. It was very much the kind of thing we were playing live. Another possible scenario is someone gave it to us. We used to get given records by American sailors. That used to happen quite a bit. We got ‘If I Were A Carpenter’ like that. It was on Top of the Pops and someone gave us a tape of it.”

The lost album tapes: ‘Sorry She’s Mine’, ‘Little Girl’, ‘The Hammer Song’, ‘Tired of Trying’ and ‘Naggin’ Woman’

“In those days you didn’t do an album, you did a bunch of singles. If the singles were doing anything, they’d put the whole lot out as an album. So we wouldn’t have gone in, and done just two tracks. We could easily have done four or five songs.”

Punk rock?

“I hated punk rock. But having said that, I can understand why it happened, because music got soft. The Who were the first punk band. The Pretty Things were punk. Punk blew away a lot of cobwebs like that glam rock thing. We had no contact with punk. They wouldn’t have talked to us anyway. After the movement settled down it got more interesting. I credit punk to this day for bringing back live drums and guitars."

The Place – Tom Thumb’s residency

“An L shaped joint, just magic, it was seriously great. It was smokey and downtown. There was the odd pimp and prostitute, the odd hood, just enough to make it exciting.”

Bruce Sontgen

“We had heard The Layabouts (Auckland R&B band) had split. Tastes were changing and I personally wasn’t keeping up with them so I rang Bruce up in July 1968 and told him to come down. I thought he had a good voice. He was pretty aware. He said basically you guys can’t play, so let’s start again. He stripped the band right back.”

Exit Sammy, Warren, and Graeme. Enter Mike and Tom

“One day Bruce came up to me and said, these guys aren’t up to it. Rightly or wrongly in my arrogance, I said OK. We had a resident job and we wanted to keep it. So Bruce and I found a guitar player we liked – Mike Farrell – hunted around for a drummer – Tom Swainson – and rehearsed with them during the day and played with the existing Tom Thumb at night. These guys didn’t know, because we wanted to keep the name out in front of the public. Someone spotted us rehearsing and told them. We played one Saturday night then went to rehearse the following day and all their gear was gone. They’d left. They went straight around the corner and formed The Wedge.”

Where did all those cool guys go?

“Twenty or thirty guys passed through Tom Thumb. A lot of people just toyed with the idea and fell away. It’s a natural elimination process. When The Relics sacked me, I said, 'fuck you, I’m better than that,' and formed a new band. When we sacked the rest of Tom Thumb, they stopped. Only one guy carried on – Graeme. He was an okay guitar player and an okay singer. He became a great bass player and a hell of a good singer. He recorded with Quincy Conserve and sang on a couple of their records. Maybe I did him a favour.”

Peter Dawkins

“We played on, kept our residency at The Place, and were also traveling and playing, getting slicker and slicker. Bruce kept getting nodules on his throat so one night we played as a three piece without him. This wee innocuous, inconspicuous guy said, ‘I’d like to record you guys’. I remember leaning on the bar, saying, ‘Yeah, so fucking what’. He said, ‘No, no, I’m a producer at HMV – Peter Dawkins.’

“We were the first act he ever recorded as a producer. He’d basically been a tea boy at PolyGram in England. He was a very, very good drummer. He went to England in 1966 with Mee and The Others with Paul Mugglestone (guitar) and Gary Thain (bass), and recorded in Europe as The New Nadir.

“He sat down with Tom Swainson, and said I want the bass drum happening, before that he was all top. I can remember Dawkins tying one of his hands behind his back in practice and saying, ‘use your feet.’ Because of that Tom has this reputation in Wellington as a drum god. People still talk about him and it’s because of his bass drum and because he played tight as hell.

"We’d fight and he was dictatorial, but he knew what he wanted. He was determined to get a hit record. So he gave us one style and it didn’t work. So he gave us a ballad, and when it didn’t work, he gave us a novelty record, and when that didn’t work he gave us a Beatles record (‘Hey Bulldog’). He tried every single thing. We had regional hits, but no national hits. ‘If I Were A Carpenter’ came close. It almost became an anthem for us. It hummed live.”

Ali Baba’s nightclub

“We opened it with The Avengers. They were recording a live album and we were supporting them. Frank Douglas and Peter Hitchcock were engineering and they used us for the tape levels. Later, Peter Hitchcock said to me, ‘you should hear the tapes, they’re great, you blew The Avengers away’.”

Managers and promoters

“Ken Cooper (infamous Wellington promoter and proprietor of The Place) was the nearest to a pro we came across. He gave us a bit of discipline and kept us on the track. The fact we fought against him made us stronger and we had regular work, a focus, rehearsal facilities, records and touring. His competitiveness rubbed off. If we went out in public, we had to behave. We were not to be seen with girls, not allowed to wear street clothes on stage and weren’t allowed to go to parties unless we arrived and left as a group.

“As we got more popular, we rebelled and were fined accordingly. He’d dock our wages. The prick would ring me up at three o’clock in the morning and say, ‘Mike Farrell, seen on the street at midnight, fined five pound.’

“We were playing at Nelson over the Christmas period, living in a tent out the back of the hall, or in a cottage over a swing bridge with slats missing. We had four bikes for transport and a tin bath, which you had to boil a kettle to get hot water for.”

The Ludgate Hill mini-epic

“I hate it. It’s a bunch of shit. Political thing. Dick Le Fort and Martin Hadlow wrote it, but we only got a minute long tape, which Dawkins wanted us to try.”

The end

“The USA music scene started to get more interesting starting with Moby Grape – not flower power bands – but rockier bands. What happened was someone gave us a joint and it was just like the 1960s again. We all started smoking dope, writing opuses and rehearsing every night, playing bands like Yes and Genesis, who were indulgent bands with one 100 songs in one. We just followed the trend.”

(Rick White’s bands after Tom Thumb – Taylor and Farmyard – who both recorded albums, had two distinct repertoires, one they learnt and never played live and one they played live.)

The non-reunion

“We talked about getting back together in 1974 as five-piece with Kevin Bayley, when I was house producer at EMI. It didn’t quite happen. Bruce was off on another tangent by then and Mike was living up North. We all had different agendas. Bruce had been through the Oz experience with Highway and I think that really fucked him around. In a band you really have to look after each other and realise each other’s strengths and weaknesses to get the best out each other.”

The 1996 reunion

“There’s been a wave of reunion and get-togethers around the country in recent years. I was involved in one in Wellington in August in 1995 playing in a scratch band with Bruce "Phantom" Robinson and Bob Smith. No rehearsal, nothing, and it went great, so this year we started talking about Tom Thumb.”

“It got real interesting! I hadn’t spoken to Mike for about 20 years, but after the first couple of phone calls, it was like we’d never been away.

“The other big advantage for us was that we still all play and the kind of R&B we were doing hadn’t gone away. We did a big pop and rock reunion in Lower Hutt on June 30, 1996 with about a dozen other bands. Around 1,200 people turned up and we blew them away. We had one rehearsal a couple of hours before the gig and just went and did it. I’m still in awe of the other guys after all this time. Mike plays great and Bruce is a real R&B shouter. We did the gig without Tom who we found in Australia only a few days before.”