Like Radio Hauraki before it, the station we now call 95bFM began at sea. During capping week in 1969, a group of University of Auckland students got together and broadcast pre-recorded programmes on a station they called “Radio Bosom” from a borrowed boat on the Hauraki Gulf.

“It was initially out beyond Waiheke,” recalls Roger Fowler, who hosted the Breakfast show as “Roger Crumpet Brain”. “But the signal wasn't strong enough, so they came closer and closer and into Okahu Bay. And the police and Post Office officials eventually homed in on where the signal was coming from, boarded the boat and closed it down.”

Unlike the Hauraki founders, the students were not budding media professionals – and they weren’t particularly good sailors either. Seasickness was apparently another factor in coming in closer to land.

“We had no concept that it would turn into a bona fide radio station that would still be broadcasting today.”

It was, says Fowler, “an extravagant capping stunt. We had no concept that it would turn into a bona fide radio station that would still be broadcasting today.”

The prime instigator was the late Dave Neumegen, who later renamed himself Arif Usmani and was best known to several generations of kids as Auntie Uncle of the childrens’ music theatre group The Aunties. Although Neumegen was never afraid of stirring the pot – he campaigned for the AUSA presidency in a Superman costume and both he and Fowler were involved in the infamous Jumping Sunday musical happenings in Albert Park – the crew didn’t attempt to repeat their short-lived piracy escapade.

Instead, they settled down to “broadcasting” via a network of speakers installed in the quad and around the campus. A “shadow executive” of students led by “President” Neumegen provided the speakers and sounds. And while they might not have been properly on air, they proved quite capable of causing trouble.

During Orientation in March 1971, AUSA president Bill Spring stated that, having received complaints about the volume of the music, the student executive would be restricting the hours during which music could be played. Neumegen declared he would ignore the edict, but backed down in the face of unspecified disciplinary action.

L to R: Richard Segedin (programming assistance, announcer, technician), Romi Patel (announcer, technician, future station manager) and Ron Imms (technician) in a vacant office on the first floor of the student union building. The technicians were working late into the night to upgrade the mixer before an on-air broadcast. - Rob Gordon Collection

“Condensed and magnified in Auckland University is all the indifference, apathy and contempt for activity that chronically afflicts our nation,” raged future Green MP Sue Kedgley in a zesty “Campus Comment” column in the Sunday News.

Although, according to Kedgley, the playing of jazz, rock and classical music had gladdened the hearts of students in a way any number of “arranged” activities had not, it remained controversial.

Technicians Pete Gronous and Neil Dudley (at front). - Rob Gordon Collection

“Loud rock music drifting from Auckland University’s Student Union building is alleged to be disturbing people seeking the tranquillity of Albert Park opposite,” the Auckland Star reported that May. Members of the faculty complained to the university council, but the new vice-chancellor Colin Maiden observed that “a fair body of opinion among certain students seems to want the music during the day,” and the council’s hand was stayed.

Neumegen scorned the council in his Craccum column – and revealed plans to expand rather than peg back the music. During the first term holidays, he had worked with local music tastemaker Selwyn Jones (who was at the time president of the university’s Blues, Jazz and Rock Society) to set up a studio in the university’s Arts Centre at 24 Grafton Road. The students’ association, he said, had not provided “one bit of help”.

“Because several of the other organisers (including myself) were connected with RADIO BOSOM – set up in 1969 for Capping Week – we have decided to call this venture RADIO BOSOM,” Neumegen wrote.

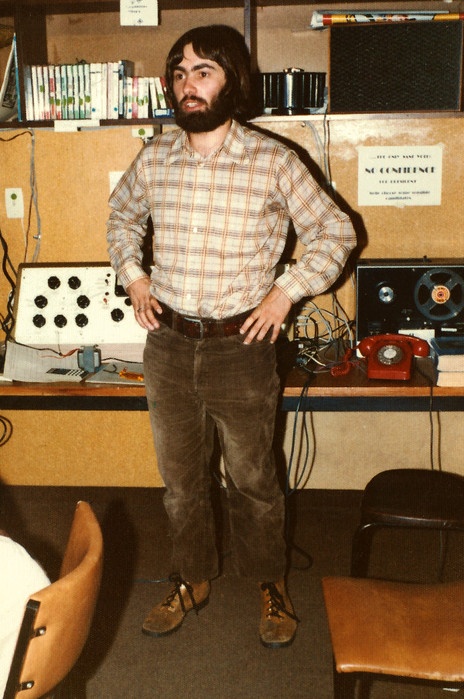

Engineer Mike Stretton. - Rob Gordon Collection

“Our ultimate aim is to apply for a private licence, perhaps next year, for it is a well known fact that the next private licence to be issued in Auckland will go to the University.”

Neumegen concluded by marking out Radio Bosom’s musical ground. “We will definitely not sell out to middle-of-the-road tastes as all the Auckland stations have; we exist only to play the music you wish to hear. Disc jockeys from other stations are to be invited to guest shows and we will be experimenting a lot, so the result should be interesting. At the very least RADIO BOSOM should encourage students to think more about music, and provide advertising for any groups who wish to use it, but it will only work if you get behind it. RADIO BOSOM for ever!”

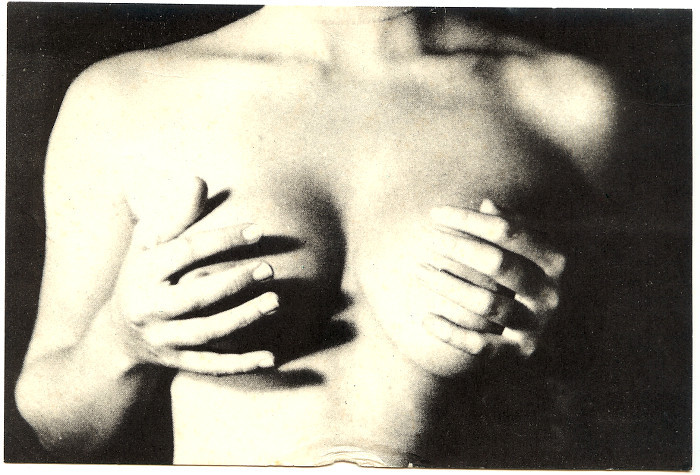

The front of a Radio Bosom QSL card, used as written confirmation of reception of a radio transmission

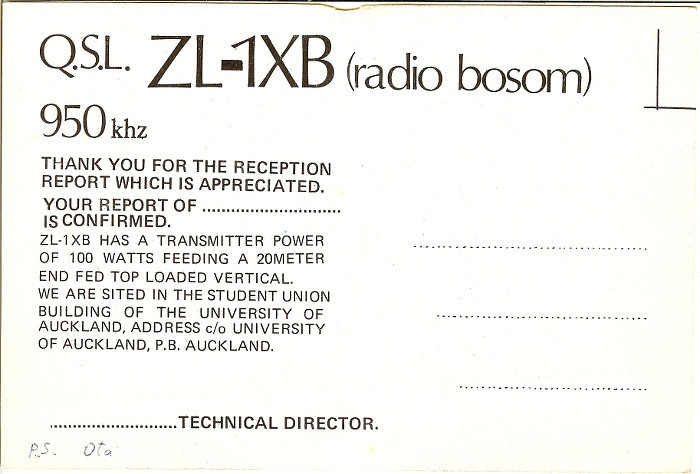

The back of a Radio Bosom QSL card, used as written confirmation of reception of a radio transmission

Glenn Smith, who became involved when the Arts Centre studio was established, and subsequently became station manager, says Jones was “the person that put it on a more serious footing. He was very serious about making it happen.”

But by the end of the year, the station had moved to the student union building, on the floor below the present-day 95bFM studio. It soon delivered staff to the early commercial radio stations Radio i, Radio Windy and Radio Avon, establishing B’s reputation as a talent factory for the industry.

But Neumegen’s “well known fact” about the granting of a licence to the university was fanciful. Even bids to broadcast a low-powered AM signal to the nearby halls of residence were rejected by the Broadcasting Authority.

Barbara Hochstein, responsible for news reading and interviews. - Rob Gordon Collection

It took the sensation caused by its pirate sibling Radio U in 1972 to finally help get Bosom to air. Although the Radio U broadcasts took place under a National government, in November of that year, the Kirk Labour government was elected. Labour rewrote the Broadcasting Act, abolished the Broadcasting Authority (and replaced it with the Broadcasting Tribunal) and made Roger Douglas the minister.

The changes meant temporary licences were certainly available in theory – but no one had ever got one. It took some direct action by Glenn Smith, by then station manager, to get the station over the line.

“Roger Douglas was the Minister of Broadcasting and he refused to talk to us,” says Smith. “So I masqueraded as one of his constituents and crashed his Saturday morning electorate meeting to talk to him about short-term broadcast licences. He was quite flabbergasted when I got to speak to him, but he basically said, put in an application and we’ll see how it goes. We did have quite a reasonable discussion after his initial consternation.”

Technician Pete Gronous. - Rob Gordon Collection

So another application was made. Even then, there was a problem with the Tribunal.

“The key thing they were concerned about, allegedly, was bad language. So they put a condition on the licence that we had to put up a cash bond of $50,000 in case there were complaints or we did something bad. In 1974 that was a huge amount of money, so we went to the university council, through Claire Ward, who was president of the students’ association – and they said yes immediately and put up the fifty grand.”

Smith suspects the Tribunal had never supposed that the student longhairs would actually come through with a bond. “It really blew their lights out when we fronted up with the money. It all got returned because there was nothing amiss. We didn't feel unduly restricted – just elated that we actually had the licence.”

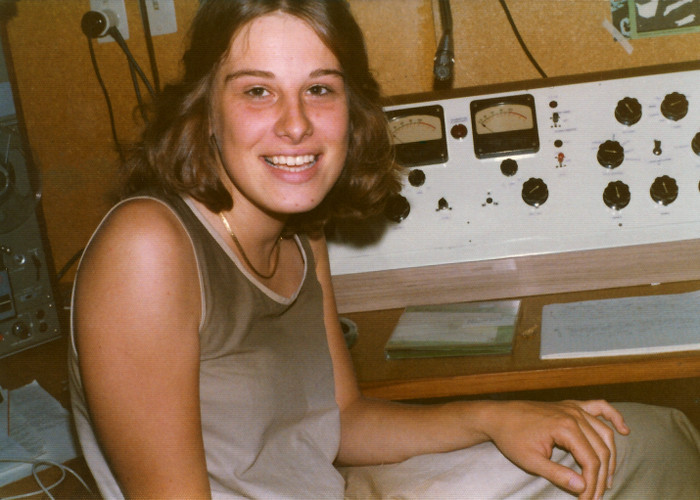

Senior announcer Julie Pendray, aged 17 or 18, circa 1974. - Rob Gordon Collection

And so, for three weeks in February 1974, Radio Bosom 1XB conducted its first legitimate broadcast. Hours were limited and there was to be no broadcasting on Saturdays, but it was the first licence to non-commercial private radio, the first to a university and the first short-term licence. The frequency, presaging the present-day “95” brand, was 950KHz. For the rest of the year, the “radio” would be delivered only through the university’s speaker network.

Given the shift in the public mood and the changes to legislation, the granting of the temporary licence was not a shock. But the terms of the warrant – authorised on the basis that the station was a student information service – were immediately problematic.

“We were meant to have six or ten minutes of music per hour and the rest had to be student-oriented talk, which was clearly unfeasible,” recalls one of the crew, Robert Gordon. “We did try to keep up with the talk, but for most of us we managed about ten minutes an hour of talk.”

Whatever the regulators said, Radio Bosom was about the music. “The music tastes we had, we didn’t have playlists,” says Gordon. “Our feeling was that we just wanted to get away from the narrow formats of the existing stations, so we were encouraging people play their own favourites. The announcers would select their own music.”

“I have memories of discovering great music that mainstream stations did not play,” says another former announcer, cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh. “We were fortunate to have the record company reps on our side. I think we were playing Bob Marley and reggae in general well before it caught on in mainstream New Zealand."

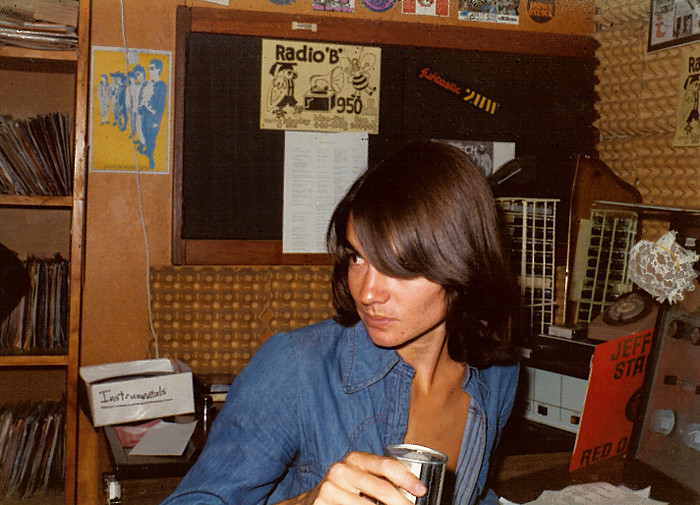

Announcer Stuart Dryburgh, now a successful cinematographer. - Rob Gordon Collection

But the government wasn’t exactly cutting the bonds. Postmaster-General Fraser Colman met with the students after the first broadcast and warned that there would not be a repeat unless the station changed its rather racy name. In the event, “Bosom” was not formally abandoned, but the name Radio B was used in polite circles.

Into what had hitherto been a boys’ club wandered 17-year-old Julie Pendray, fresh out of Mangere College in 1975. Students were encouraged to enrol in clubs, so she chose Craccum, Radio B – and The Winnie the Pooh Society.

Senior announcer Julie Pendray. - Rob Gordon Collection

“It was months before I got the courage to go introduce myself quietly. Robert was there that day,” she recalls. “He said, ‘we’ve been wondering where you were. We saw that you’d signed up.’ He asked me what I’d like to do. I didn't have a clue about their volunteer job descriptions, so I said, ‘I’ll file records in your library for you.’ Robert said, with a big smile, ‘No you won’t. You’ll be our first female DJ!’”

Pendray gradually went from being too nervous to say more than a few words between the records to, at the age of 18, winning a “female DJ” competition run by Radio Hauraki and becoming that station’s first woman on air: “It was very exciting to be doing that at such a young age”. She has since worked in TV, radio and newspapers in the US and still keeps in touch with the B crew. “Those guys are like my brothers.”

Radio B attracted the same kind of creative, enterprising, slightly strange kids that 95bFM does today.

There was also the odd invasion by sisters. “I remember being hijacked by Sue Kedgely and her team of black-clad feminists one lunchtime,” says Dryburgh. “They burst into the studio and demanded to be given the mic. I happily stood back and obliged, offering tech support when needed.”

Radio B attracted the same kind of creative, enterprising, slightly strange kids that 95bFM does today. Perhaps the big difference was that quite a few of those kids could actually build a radio. They were directly responsible for Victoria University’s Radio Active getting to air, after a team from Auckland travelled to Wellington and set up Active’s first transmitter. One particularly rebellious technician, Tim Stanton, is now an oceanographer in California.

Others on the crew went on to make names for themselves both on and off the radio. Journalist (and later respected parliamentary press secretary) Fraser Folster headed the news team and covered the station for Craccum. John Sweetman followed Pendray to Hauraki and eventually became the continuity “voice” of TV3, which he remains today. Larry Summerville, later head of More FM, was a host, as was future Auckland City councillor Glenda Fryer.

Senior announcer Larry Summerville. - Rob Gordon Collection

Another member of the team, Pat Courtenay, headed to Ireland and on-air roles with the hugely popular pirate stations Sunshine, Energy and Nova – he returned to New Zealand in the 1990s to be breakfast host on the new Classic Hits, but is now back in Ireland with the licensed station now broadcasting under the Nova name.

DJ Pat Courtenay, now a radio host on Dublin-based radio station Nova. - Rob Gordon Collection

Smith himself went to the first regional independent station – Whakatane’s 1XX – in 1974, and never left. Now the manager of the still-independent 1XX, he received a special radio award for services to broadcasting in 2013 and the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2014.

Radio B saw out the 1970s as a legitimate but very much part-time station. The 1980s would see much greater things.

--

Russell Brown on bFM’s later years

A history of New Zealand student radio, by RNZ's The Wireless