Whenever the Civic Theatre is mentioned in a musical context, two memories always come up. Auckland music fans now looking at 70 mention the Rolling Stones, who played there in 1966. Those much older than 70 recall something much more prosaic: the barge. This was a gimmick that, from its opening night in 1929, always made the Civic different and – with the Milky Way of twinkling stars in the main theatre’s ceiling – unforgettable.

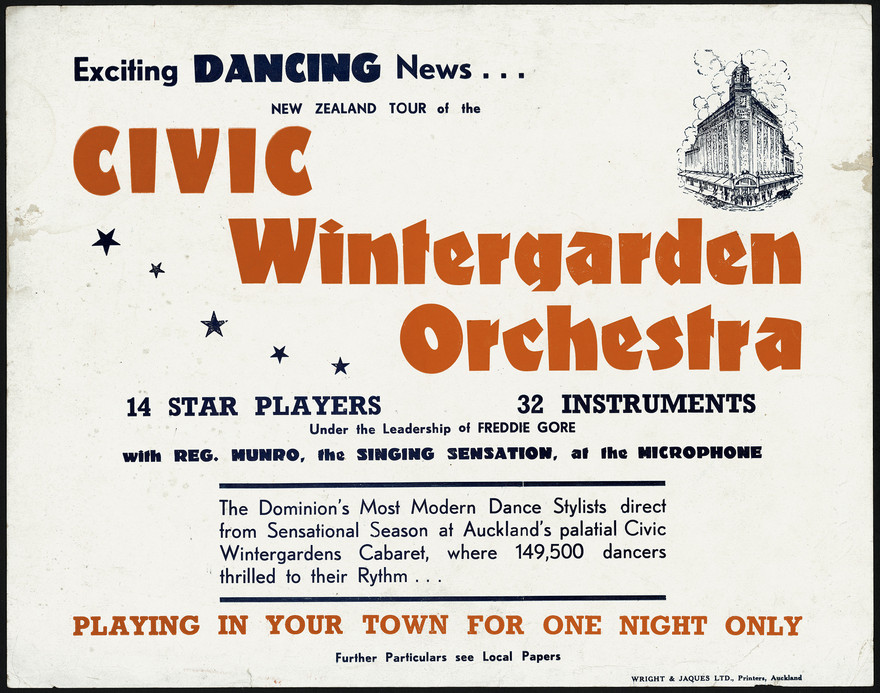

A 1945 flyer announces the national tour of Freddie Gore’s big band, direct from Auckland’s Civic Wintergarden. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, Eph-C-CABOT-Music-1945

“The barge” was a moving bandstand – elevated by a hydraulic lift – that would appear in the main theatre during intermission, with a big band pumping out a brass-heavy swing tune. This was high-class entertainment – and a tease. The message of this burst of music was: “After the film, head to the Wintergarden cabaret below the cinema for dancing”. There, some of the best bands in New Zealand provided music for well-dressed patrons, from 1929 until 1955. By then, young couples were going to the Trades Hall up in Hobson street; they would soon be dancing to rock’n’roll and, shortly afterwards, the Civic would enter the doldrums with the arrival of television. It sat on its prominent corner site, deteriorating and unloved except by children, under threat of demolition until the 1990s when finally Auckland citizens said Enough to the destruction of the city’s character.

For 25 years the Civic was as much a music venue as a cinema, with the main action taking place for the dancing elite in the Wintergarden. Not until about 2000 – soon after a $50 million refurbishment – was it once again appreciated as a music venue. Was it the celebratory package of Bic Runga, Tim Finn, and Dave Dobbyn that first made the seats dance again? In the 2000s the ceiling’s stars have witnessed Bob Dylan, BB King, Al Green, Emmylou Harris, Brian Wilson and many other overseas and New Zealand acts. The idea of the Civic without songs is again unthinkable.

The Civic from a musician's point of view. The stage is set up for Bonnie Raitt's concert in April 2017. Photograph by Craig Wilson

Neil Finn in the Civic Theatre, Auckland, 2001 - Photo by Karin Catt

On the opening night of 20 December 1929, the packed house was presented with a stage decorated with palm trees waving among minarets under the night sky. The audience heard a fanfare of trumpets from an unseen band; this soon appeared as the barge came up through the stage, decorated as a gondola. The band was a 30-piece orchestra led by Ted Henkel, an American based in Australia. Among the musicians was Frank Coughlan, soon to be one of Australia’s top band leaders.

“Under the baton of Mr Ted Henkel,” reported the Herald, the musicians “stole into Ponchielli’s ‘Dance of the Hours’. Vitality and fire shone through the interpretation of the sparkling music and Mr Henkel marshalled to perfection the resources of his players. He is a musician for whom Auckland should be thankful.” After a set of light classics, the band then showed its other side: its showmanship. “It was a demonstration of the force of personality. The band appeared in an elaborate staircase setting with a background representing the ‘Sunrise of the New Show World’. Two numbers were played by the band, a novel arrangement of selections from Faust, and an engaging melody, ‘I’ll Always Be in Love With You’. The performance of both was crisp and clear and Mr Henkel showed that he has developed fully the gift of originality in his orchestrations.”

The music was only one attraction that night: there were also acrobatics, ballet dancing and a recital on the ‘grand organ’ which closed the evening. This, said the Herald, “was alone sufficient to send the audience away with feelings very much akin to those which made Oliver Twist famous.” But then the lights lowered for the debut film attraction: Three Live Ghosts. The film was silent, even though the Civic’s competitors lower down Queen Street were already showing talkies.

Stan Hills, Auckland dance band trumpeter from the 1920s to 1950s; he is the source of the magnificent Civic photos from the 1930s.

A collection of photographs that were offered to AudioCulture to share reveals the lavishness of the Civic’s musical productions in the 1930s. The photos were from the album of Stan Hills, a trumpeter in leading dance bands from the 1920s to the 1950s. The productions are like Busby Berkeley in the South Pacific, with costumed dancers, actors and musicians performing in exotic stage sets that rose high into the proscenium arch. The “themed nights” were often Arabian, but sometimes nautical, Spanish, colonial or Olde English.

The bandleader who was associated the longest with the Civic and the barge was Ted “Chips” Healy, who led the band from 1932, and played right through the Depression at the Wintergarden, and the war years, until 1955. Healy, a saxophonist who would have a blow after taking a large cigar out of his mouth, was one of the most colourful characters in Auckland music. Up until the early 1980s young musicians and ageing jazzers would seek him out in his Queen Street workshop where he repaired reed instruments.

“Chips, what can I say about him,” said trumpeter Jim Warren in 2006, looking back on an association that began 70 years earlier. “He was a cunning old fox, you could say, a very slippery character in some ways, and I had a lot to do with him in the music business at times. I always got on well with him [but] he was a tricky bugger! For instance they used to import instruments that I’d want to buy for Beggs and I’d go up and say can you sell me some of those clarinets, ‘Oh yes, they’re £39 or 39/10’. So I’d say, well I’ll get an order and when I went back they’d be £57, that type of thing. ‘Oh no, no he’d say, that was the wrong price I gave you, no, can’t sell you that, I’d be losing money.’ That’s why he had the name Chips, he was always after the chips.”

Chips Healy Band on the Civic stage

Bass player for Healy in the 1930s was Spike Donovan who, before he died in 1984, recorded his memories of early Auckland dance bands. “At the Civic we started playing as soon as the picture had finished … we’d sneak onto the bandstand five minutes before the end of the picture while everything was in darkness, then we would come up as the picture finished, blowing lustily, popular tunes of the day or perhaps an extract from that particular picture.

“After we’d played that number we’d go down again to the lower level and start playing for the dances. This particular night that I have in mind we had a very good trombone player named Jack Evans there … Evans was climbing up to the back [of the bandstand] but with an eye on the picture, and all of a sudden he fell all over Frank Condon’s drums. Frank had quite a fair size outfit of drums and the drums fell down and went rolling down the steps, bang, clatter, crash – cymbals falling. Poor old Jack he was most confused and Chips, who in the ordinary way was a good-tempered man, quite a good band leader to work with, was rather perturbed because we were just due to start playing and he said bitterly to Jack, ‘Now kick the bloody thing!’”

Healy, said Donovan, was a good bandleader who paid good money. “He was paying professional wages and he expected professional conduct and ability and that was as straightforward as that.”

The 1930s were not all boom years for the Civic or its band. In 1936 the number of musicians was temporarily cut down from 12 to six. The hours were very tough on the band – they began before the film and played in the cabaret until 1am – so they would have welcomed the back pay they received in 1937, the enormous sum of £400. In 1938 there were reports that the gig “appears doomed”. But during World War II, it bounced back as a venue with the arrival of tens of thousands of US Marines, who loved to dance, and the Auckland women who loved to dance with them.

Bert Peterson, seen here with his band at the Metropole in Upper Queen Street, was the bandleader at the Civic during World War II.

During the war, while Healy was in the RNZAF band, the Civic bandleader was Bert Peterson. On Friday and Saturday nights, they would play to crowds of 3,000 people. The Civic was “now the rendezvous of the elite” wrote the Australian Music Maker in 1943: officers and their glamorous dates. But there were many other venues for the lower ranks.

Veteran dance band trumpeter Vern Wilson recalled in an oral history, “During the war at the Civic, the Navy boats used to cable in for a dance after the films. They’d take the whole Civic [dancing to] Chips Healy’s band. They were great dances, they would bring up 44 gallon drums with ice and beer. There was always lots of beer left over. We got it: I used to park the car outside the Civic. One night, two policemen were out there, and I had bottles under my coat. I dropped the bottle, and it smashed. The policeman said, ‘Come here. Get that off the footpath!’ He didn’t lock me up, he was very decent.”

The moment New Zealand jazz fans never forgot occurred in August 1943, when Artie Shaw’s Navy Band visited. In effect Shaw’s band was a top US swing band, led by the star clarinetist (‘Begin the Beguine’) who, after joining up, recruited many top jazz players and friends. Late in the evening of 10 August, several black American GIs were brought in to the Civic Wintergarden cabaret. On the stage was the Artie Shaw band. Aspirant entrepreneur Pat Quinn – who later had an international career as the hypnotist, Franquin – had managed to secure the band for an appearance at the Wintergarden during its visit. But it was the black dancers giving a jitterbugging display – flying about with abandon – who stole the show.

The musical highpoint of New Zealand jazz at the Civic came nearly two years later when the war ended, and Wellington bandleader Freddie Gore formed a band to play at the Wintergarden for a couple of seasons, after the sudden departure of Bert Peterson. Gore was a cutting-edge jazz band leader, who arranged not in the “sweet” style of Glenn Miller, but challenging, like Stan Kenton combined with Freddie Slack

It was at the Civic with a 14-piece dance orchestra that Gore – and many of his musicians – really established their reputations. In May 1945, with Esme Stephens and Reg Munro as vocalists, they performed at a patriotic premiere hosted by the Civic for the Irving Berlin film This is the Army. Twice a week the Gore band filled the Civic Wintergarden, receiving wide acclaim. By the end of the year, they were hired by Warner Brothers to go on ‘the biggest national tour ever attempted by a big band in New Zealand’. Advertisements for the tour informed small towns of the scale of what they were about to experience: “modern dance rhythm stylists that 149,500 paid to hear in their sensational cabaret season in the palatial Civic Wintergarden, Auckland – 14 Star Players – 32 Instruments – The Top Tunes of the Hit Parade, with the singing sensation, Reg Munro, at the microphone.” All for five shillings.

A female singer who, after the war, tried a stint with the Healy band, was Mary Throll (later an artists’ agent with Fuller’s). “I auditioned for a spot with the Chips Healy Big Band at the Civic Wintergarden,” she recalled. “This was a complete departure from my usual style as I had always been a ‘floor show’ singer, mainly on stage or in clubs, cabarets, or broadcasting. Never having experienced the metronome-type restriction of a big band, I hated it, but as Chips had kindly given me a six-month’s contract as the band’s vocalist, I had no option but to persevere – and persevere I did, every Friday and Saturday.

“When the current Civic film ended, the band emerged with a flourish on a barge-type contraption, no doubt hoping to entice the patrons to come downstairs to the Wintergarden. This seemed to be successful, as we were always crowded. The Civic Wintergarden was a very popular place in those days. The Chips Healy Band was a large one – 10 piece – and they had a reputation as one of the best bands in Auckland. I loved their polished ‘Glenn Miller’ sound, but performing for them was simply not for me, and I was relieved when the binding contract ended and I was free to go back to ‘proper show business’.”

In June 1955, the Civic Wintergarden suddenly closed, and Healy and his musicians – once again down to a sextet – were out of a job. The Wintergarden would eventually become a micro-cinema and an all-purpose function centre. Several other venues took up residence in other parts of the building. Upstairs in the main theatre, until the theatre’s restoration, the flurry of beat bands that played there in the 1960s was the main music heard by the stars above.

Supergroove at Auckland's Civic Theatre, 5 September 2008 - Photo by Charlette Hannah. Courtesy of Auckland Live Music.

Now, the Civic has long left behind its beginnings as a folly from the late 1920s, and its neglect from the 70s to the 90s, to become a permanent part of Auckland’s music scene. If only His Majesty’s, the Gluepot and so many others were so lucky.

Read The Civic by Peter Wells here