The New Zealand premiere of Hair opened to great fanfare at His Majesty’s Theatre in Auckland on Saturday, 26 February 1972. It had been a long time coming and the lead-up had been tantalising.

The American countercultural “tribal love-rock musical”, written by James Rado and Gerome Ragni (book and lyrics) and Galt MacDermot (music), opened on Broadway on 29 April 1968 after a six-week off-Broadway trial season in New York’s East Village and several weeks at the Cheetah nightclub.

Wellington's Evening Post welcomes Hair, August 1972.

News of its edgy content of youth-based pro-love, anti-war, civil rights themes, controversial simulated sex and drugs scenes, and – quel horreur! – a nude scene had broken first and the news of the world took note. The open-minded were intrigued while the establishment blanched or blustered with moralistic fervour.

The unruly, long-haired, high-energy tribe in shabby hippie garb danced and sang on a set that resembled a rubbish-strewn inner-city block. They moved in and among whichever audience they faced, smoked dope on stage, apparently (to all intents and purposes), swore loud and often, and sang raucous anti-social and protest anthems to an onstage rock-band accompaniment. Audiences, who were virtually corralled within the experience, were invited onto the stage at the end of the show to be part of the “be-in”.

This wasn’t the sanitised, singalong musical theatre of yore, with stage and auditorium, actors and audience carefully delineated and separate. There was intermingling. And while some musical shows and opera theatre had long presented realism on stage, and others made moving and breakthrough theatre pieces with powerful music (West Side Story, and Porgy and Bess, for example), Hair burst through the conventional theatre barricades and broke down the walls.

Hair ticket booklet, Opera House, Wellington, 1972. - Linda Scott collection

Theatre critics sharpened their red pencils and let fly with both invective and superlatives. While the critics were not all in accord – conductor Leonard Bernstein, for example, thought the music sub-par and walked out – shining reviews well outnumbered the naysayers and audiences flooded in. Clive Barnes, influential critic for the New York Times, wrote that it was “the first Broadway musical in some time to have the authentic voice of today rather than the day before yesterday”.

A 1968 original cast recording, which won the writers a 1969 Grammy Award for best score, was the first taste of Hair for New Zealand audiences. Its instant emblematic pop-rock classics, like ‘Good Morning Starshine’, ‘Hair’, ‘I Got No’, ‘Frank Mills’ and ‘Easy to be Hard’, received much airplay from either the original album or cover artists such as the 5th Dimension’s chart-topping double-header ‘Aquarius’/‘Let the Sunshine In’ and the Cowsills’ version of ‘Good Morning Starshine’.

The show’s popularity in America led to numerous seasons and revivals in other centres. By 1970, widespread international interest had sparked satellite productions in London, Paris, Stockholm, Tokyo, Germany, Israel, Tokyo, Brazil, Italy, Switzerland, Canada, and the Netherlands, among others. A production in Belgrade, Yugoslavia was the only one behind the Iron Curtain. Where a production nation’s first language was not English the show was translated into the home language, with nationally appropriate political and satirical allusions inserted in places to give it regional relevance, while remaining faithful to the writers’ overall content and the original staging.

Meanwhile, across the Ditch, impresario and expatriate New Zealander Harry M. Miller, who was never short on initiative or business prescience, had seen the show’s potential and acted quickly, gazumping many of the international seasons with his perfect timing. He obtained the rights, travelled overseas to see various productions, instructed director Jim Sharman to audition in the US to fill vacancies for African-American parts, and opened his Australian production at the Metro Theatre in Sydney’s Kings Cross on 4 June 1969. It was drawing closer to New Zealand.

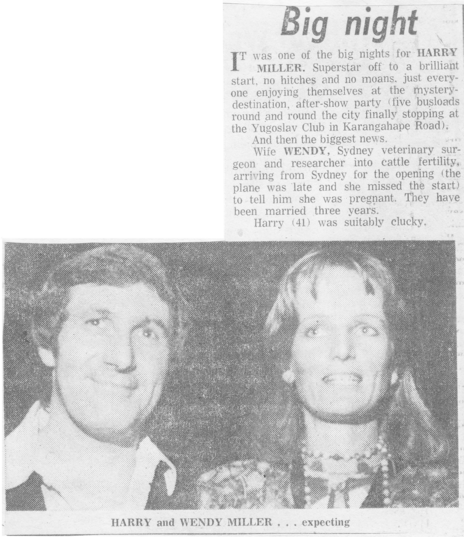

Great expectations: Harry and Wendy Miller at the opening night of Hair, Auckland.

Harry peopled the Hair tribe, as the cast was known, with a mix of actors and dancers who could sing, and strong singers who could move and act or be taught to, each of whom had a distinctive look and presence, with the goods required to inject all the vigour the non-stop, two-and-a-half hour show demanded under the direction of youthful theatre luminary Jim Sharman. Sharman had directed Shakespeare and opera, and was considered one of the top-10 theatre directors of the time.

Before it crossed the Tasman, some 10.5 million people around the world had seen Hair. Over two years at the Metro in Sydney, some three-quarters of a million people saw the Australian production and the Melbourne season attracted around 300,000 people. When it was announced that the show would open in Auckland, advance ticket sales exceeded 32,000, which included bookings from individuals as well as multiple group bookings from social clubs and so on. Tickets were in high demand.

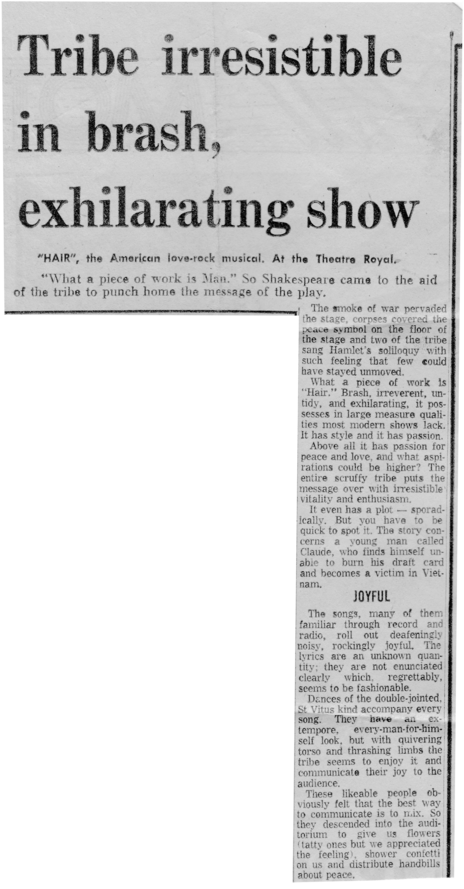

A review for Hair at the Theatre Royal, Christchurch, 1972.

Opening night in Auckland was all that it promised to be. His Maj rattled to the tribal chants of “beads, love, freedom, happiness”, feet and beats pounded, and incense filled the air. Harry had flown in from Sydney to attend and put on a characteristic first-night hooley for cast, crew and selected guests.

The late Iain Macdonald – latterly of London as a Fleet Street journalist and film, theatre and television critic before becoming the New Zealand Herald critic – reviewed it on the Monday following as, “Simply terrific …. Not so much a show as an irresistible experience”. Poet and playwright Bruce Mason, whose review appeared in the Listener, wrote: “ ‘Hair’ is a brave and beautiful piece, at once liberating and integrating. All theatre that follows will have to be sounded against its ringing and triumphant affirmations.”

Not everyone was happy. The righteous burghers of Auckland railed against what they perceived as the show’s depravity and indecency. Its content was an affront to the public standards of the day, they suggested. The filth on show would corrupt and entice vulnerable viewers. It should be stopped. The proverbial hit the fan on the Monday. There were rumours of judicial interference and, on the Tuesday, this eventuated. Sir Roy Jack, the then Attorney-General, authorised a police prosecution of the promoters and producers of Hair re Section 124 of the Crimes Act, the specifics of which cover the “distribution or exhibition of indecent matter”. Sir Roy had reacted to a senior police officer’s impressions of the show from his attendance on opening night.

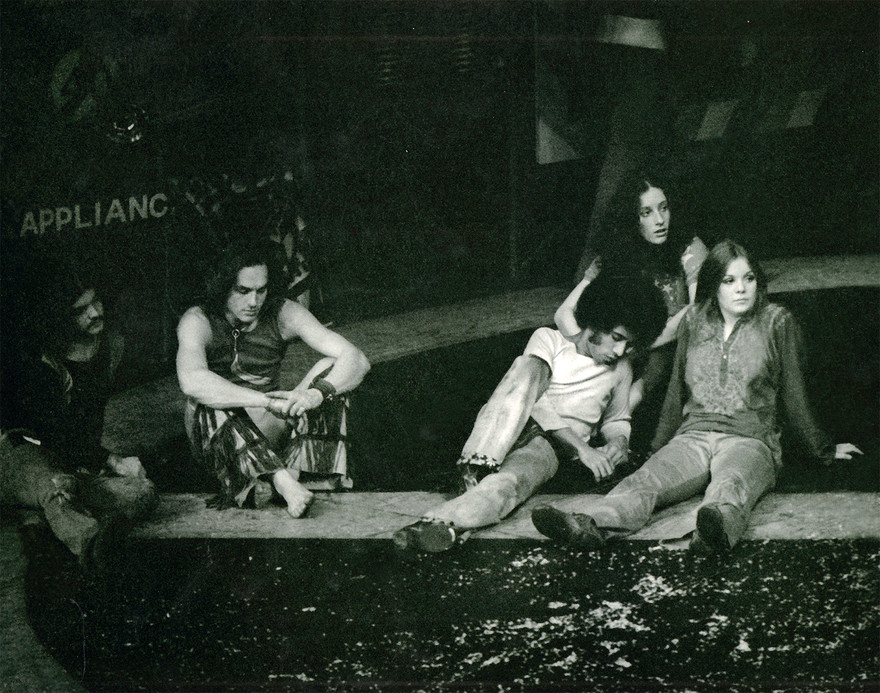

A scene from Hair - Rosa Shiels is at back right.

Detective Chief Inspector E G Perry, of the Auckland CIB, was instructed to serve a summons on Mr L W Brown QC, counsel for Hair promoters Harry M Miller Attractions Ltd. After a three-hour hearing in the Auckland Magistrates’ Court to hear the charge read – presentation of an indecent show in a place to which the public had access – Mr Brown pleaded not guilty on behalf of his client and opted for a trial by jury in the Supreme Court.

This would be New Zealand’s first prosecution of a theatre show for indecency.

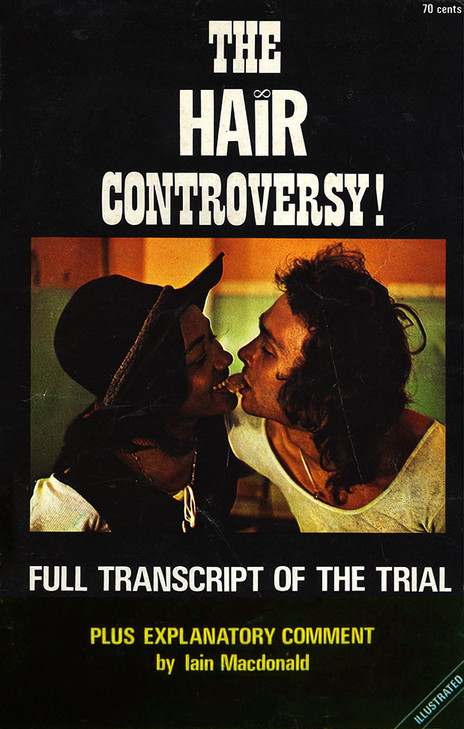

A transcript of the three-day trial, titled The Hair Controversy, was published by Auckland’s Comill Publications in March 1972, with additional and often tongue-in-cheek commentary by the Herald’s Iain Macdonald.

The Hair Controversy: the book of the Auckland trial for indecency.

In light of today’s either permissive or inclusive social standards, depending on your viewpoint, the transcript and witness statements make for fascinating and often laughable reading. Western society has moved on considerably since then and many proponents of the show hold its then-brave and confrontational standpoints as directly or indirectly responsible for social change.

The judge, Mr Justice McMullin, presided. First among the three witnesses called for the Crown by prosecutor Mr D S Morris was journalist Pat Booth, assistant editor of the Auckland Star, who later coined the nickname “Mr Asia” while covering the drug syndicate and wrote extensively about the Arthur Allan Thomas case.

Macdonald writes that Booth was “shocked and disgusted by some of the language and the actions” onstage.

DCI Perry, appearing next, explained at length what he saw, and what he had deemed indecent, providing some technical explanations for the benefit of jury members. “These included,” writes Macdonald, “apart from mere reporting of the use of ancient Anglo-Saxon copulatory and excretory nouns and verbs, some clinical definitions of terms such as sodomy, pederasty, fellatio and cunnilingus.”

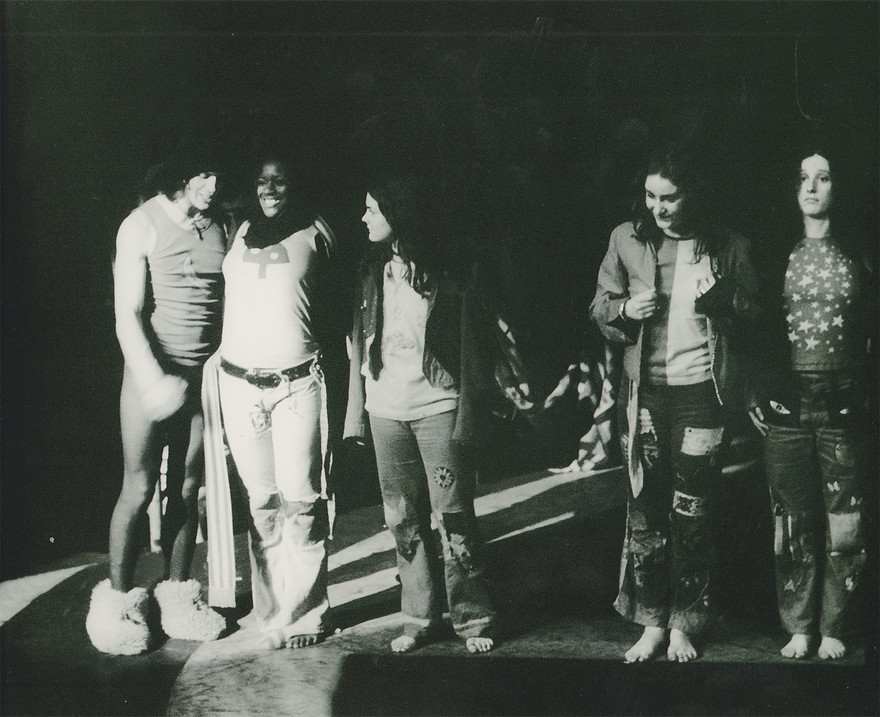

A promotional photo for Hair. From left: Vivian Grey, Peter Noble, Michelle Rupena, Ken Gregory.

For the final witness for the prosecution they called a Whakatane secretary who had travelled to see the show. She was upset by the four-letter words and various simulated sex acts.

In a synchronous legal double-whammy, feminist Dr Germaine Greer, who was touring New Zealand at the time, was busy colouring her own “pungent polemical utterances” in blue lingo wherever she lectured. She was summonsed to her charges of using obscene and indecent language and appeared in the Auckland Magistrates’ Court the day after the Hair representatives had been there. Dr Greer was found guilty of using obscene language, fined $40, and left the country, saying it was “full of humbug”.

Defence counsel for Hair had requested that the jury see the whole show so that any evidence could be seen in context. The 11 witnesses then called ranged from theatre and music specialists, journalists Macdonald and Marcia Russell, one former and one current minster of the Church, a theatre-graduate cast member and a professor of music.

Apart from the stance of prosecution witnesses DCI Perry and Pat Booth, who maintained their opposition when questioned, the opinions of each of the defence witnesses were in concert. They all believed that Hair had intrinsic artistic and theatrical merit, was current and relevant, and was serious about and true to its central pro-love, anti-war, anti-hypocrisy themes. The cast was disciplined, the lyrics were clever and thought-provoking, production values were top class, and the music, while too loud for some and not to others’ taste, was of high quality. Moreover, the witnesses all agreed that the verbal vulgarity and sex scenes were exaggerated to the point of caricature.

A scene from Hair - Rosa Shiels at far right, Marcia Hines second from left.

“As I see it,” Iain Macdonald testified, “the writers of ‘Hair’ define as obscene not bare bodies or commonly used cuss words but rather things like war, violence, cruelty and bigotry.”

The Reverend F R Hamlin, the New Zealand Presbyterian Church’s then-director of education, found the nude scene to be of “profound religious significance … the hope of mankind in all its troubles is to drop all barriers. The symbolism of nudism was this; all barriers had to be down, we had to completely expose ourselves to others.” He compared the central, peace-loving character of Claude – who had been drafted into the Vietnam War and was facing imminent departure – as being Christ-like in his vulnerability. “Claude comes onto the stage in a white robe. To me that almost conveyed the impression of a transfiguration of our Lord.”

Distinguished composer Jenny McLeod, then Professor of Music at Victoria University, was deeply moved by the show. “To put it mildly, I was staggered,” she said. “… in terms of what I would call emotional highpoints or climaxes in ‘Hair’,” she said, “I found more than I have found in any other live experience I have seen. I would be proud if I could do the same thing myself on such a scale.”

She found the moments in the show that were especially moving were those that enabled the audience to “transcend themselves, able to get beyond their petty concerns and join in the brotherhood of man” and compared the effect of this to that of the Bach Passions.

On the third day, Harry Miller rose to take the stand. When the prosecutor suggested that three of the protest banners with offensive language could be dropped out of the show to little effect, Harry parried with the reply, “I suggest that you can take four notes out of a concerto and suggest it is the same concerto.” If certain banners were dropped, Harry said, “I would be totally dishonest if I pretended that I had put on the authors’ show. People pay to see a show. I should honour the obligation to produce it.” He saw the themes of Hair as being “tolerance, love, understanding and a total disgust with war, senseless killing and hypocrisy”.

Others appearing before the prosecution and defence made their final submissions included playwright Bruce Mason: “For people of my generation it showed the young, their hang-ups, enthusiasms and hopes, more vividly than I have ever seen portrayed.” He added the production was of tremendous vitality with great technical resources, such as a virtuoso lighting display.

In summing up the main points for the jury the next day, Mr Justice McMullin said the jury had to consider whether show’s content offended public decency and social standards regarding religion, sex drugs and so on. He suggested the jury might “wonder why, in 1972 matters of obscenity were dealt with by a law made in 1908”, but said that definitions of indecency were elastic. “But if the over-riding effect of the show is to call the attention of society to matters in which society’s attention should rightly be awakened,” he said, “then the public good may be served.”

The jury filed back into the courtroom at 12.25pm ...

When the jury filed back into the courtroom at 12.25pm that day and pronounced the Not Guilty verdict, the courtroom erupted in cheers and clapping. The only other international cities that had found any parts of the show objectionable had been Melbourne, which questioned the use of a naked flame on stage; Boston, which found use of the US flag irreverent; Mexico, which closed the Acapulco show after one night for being a corruptor of youth’s morals; and Tokyo, which cut its season short after prosecuting five cast members for smoking marijuana.

It’s a showbiz truism that any publicity is good publicity and the court case boded well for full houses wherever Harry M Miller Attractions’ production of Hair: the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical played thereafter. This included Christchurch, Dunedin and Wellington before returning to Australia for seasons in Perth, Adelaide, Brisbane, Hobart and finally Launceston where it closed some four years after its 1969 premiere at the Metro Theatre in Kings Cross.

As Macdonald reiterated in his extended commentary accompanying the transcript of the New Zealand trial for indecency, “The one factor which was never in doubt was the show’s basic philosophy – freedom of the human body and spirit and a loathing of cant, cruelty and soulless materialism.”

--

Read: Inside the Hair tribe, by Rosa Shiels

* Trial reference material and quotes are from The Hair Controversy! Full transcript of the trial, plus explanatory comment by Iain Macdonald, edited by Neil Illingworth (Comill Publications Ltd, Auckland, March 1972).