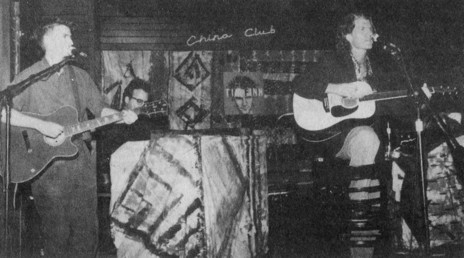

Los Angeles, April 1989 – Even on a Monday night, Hollywood’s hip come out to play. Dressed in black leather and teased hair, impenetrable shades and (the males) with stubble just so, 200 scene-makers fill the China Club, a small venue off Sunset. They rub shoulders with Roger McGuinn, Nick Seymour, and Paul Kelly, slug back a few free Coronas – and take in a show by Capitol’s latest signing, Tim Finn.

Tim Finn's 1989 showcase gig in LA, with brother Neil; Mitchell Froom on keyboards. - Rip it Up Archives

He’s the one dressed in tapa cloth (like an ethnic Hawaiian shirt to this audience) flicking long curly hair out of his eyes and strumming his acoustic with intensity. That’s his brother Neil beside him, the Crowded House guy – though he’s not doing much with his guitar, just grinning broadly.

The serious pair at the back of the stage? Mitchell Froom and Richard Thompson. Froom is playing Hammond B3 organ and bass pedals in this pick-up band; he deserves a night “off” after producing new LPs for Thompson and Tim Finn. Thompson shuns the limelight, but manages to stun the audience with his unique guitar work.

Tim Finn's self-titled second album, produced by Mitchell Froom (Capitol, 1989)

But Tim Finn sends them home impressed. His new songs have more impact live, and punchy old favourites like ‘I See Red’ and ‘Six Months In A Leaky Boat’ force a reaction from the Enz stalwarts present. Tim throws himself into the music with an energy that cuts dead the El Lay mellowspeak. Paul Hester helps Alex Acuna on percussion, and the Finn brothers trade spirited harmonies on South Pacific standards such as ‘Throw Your Arms Around Me’. With references to Taranaki, Te Whiti and Parihaka in Finn’s new songs, all that’s missing are Vegemite sandwiches in the buffet.

The concert over, ‘How’m I Gonna Sleep’ appears on the video screen, with its scenes of actress Greta Scacchi and Auckland. Will the FM programmers present give it airplay?

Later in the week, inside the mock-Tudor A&M complex that once housed Charlie Chaplin’s film studio, Mitchell Froom says the Tim Finn showcase was “scary, but fun.” There was no rehearsal and Froom had to play organ and bass simultaneously, “but it came off well. Tim took the reins and made it happen. We were trying to play as subtly as we could, but make the songs sound bigger than if Tim was by himself. Neil was great, he broke up a lot of the tension – and to hear them sing together is about all you could ask.”

Neil seemed to glow with pride at his brother’s performance – a reversal of the early Enz days, when Neil was the new kid on the block. “Tim’s been out of performing and out of the limelight, while Neil has really developed. He’s been on stage so much in the last couple of years, he’s got a whole different voice and demeanour. He’s very relaxed, whereas Tim has to get back into the flow of it.”

Mitchell Froom, 1998. - Publicity photo

On stage Froom is about as flashy as a bank clerk. There’s a modesty about him, an unpretentious intelligence that comes across in his music. Producing ‘La Bamba’ for Los Lobos is his biggest success – a US No.1 in 1987 – but an embarrassment. “That’s a joke: two days’ work!”

Froom’s connection with Tim Finn came about when Neil gave his brother a tape of Froom’s instrumental music for Slamdance. “Tim called me, said he really liked it and thought it might go well with his music. He started sending me tapes of just him at the piano, and then came through LA when I had some days off. So we just got together and played for three or four days.”

They recorded into Froom’s blaster box and he took the results to Capitol. “They said, ‘Great, go make a record.’ It was an incredible three days, like two guys getting together and forming a group and getting a contract.”

Froom says Neil’s involvement in their meeting was quite indirect. “It was good because if Tim had called me – as great as I always thought he was – and said, ‘I like the Crowded House record, let’s do something like that,’ it’d be the last thing I’d want to do. Whenever you try to copy something, it’s always second generation, never very interesting.

“Also, the last thing I really wanted to do was get in the middle of two brothers. What if one doesn’t like the other’s work, where does that leave me? What if someone promotes this guy more than the other and is successful? But I thought, if I don’t do this, it’s just stupid.”

“NEIL LOVES TO SING IN THE STUDIO; WITH TIM YOU HAVE TO CREATE MORE OF A PERFORMANCE ATMOSPHERE.”

Before his work with Crowded House, all Froom knew of Split Enz’s music was the few singles that received US airplay. “I always liked them but I wasn’t what you’d call a diehard fan. Actually, that helped – I’ve just worked with Richard Thompson [on Amnesia], who has got a real core of devoted followers. If you’re a huge fan, there’s an intimidation factor and also a notion of the music’s not quite fresh. I like it when they seem like brand new artists.”

“But in a lot of ways they’re similar because they were around each other when they used to write.” The best moments of the showcase gig – and also in the punchier songs on the first Crowded House LP – reflect their upbringing of belting out songs together on acoustic guitars. Froom would like the pair to make a simple acoustic album together, “just for fun.”

The two brothers have quite different approaches in the studio, he says. Apart from the fact that “one is a band, the other isn’t,” Neil concentrates on his guitar while Tim dabbles with various instruments. “And they’re very different in that Neil loves to sing in the studio, whereas with Tim you have to create more of a performance atmosphere. He doesn’t like being in a dark room, having a track come up, and trying to sing. I really saw that at the show – he thrives on the live performance.

On Tim Finn’s album, the same group of session musicians played on each song. Finn and Froom both played keyboards, David Rhodes guitar, and Tony Levin bass (both have worked with Peter Gabriel), plus the ubiquitous Jerry Marotta and Alex Acuna played drums and percussion.

For Froom, the highpoint of the sessions came when the tracks to several songs were down: ‘Show a Little Mercy’, ‘Not Even Close’, ‘How’m I Gonna Sleep’ and Tears Inside’. “Tim said, ‘I’ll just go out and sing these songs, just run ’em in order.’ And the way he sang was just beautiful – almost all of it is on the record. I couldn’t believe it. It was because he wasn’t thinking about it, and he hit this emotional peak.”

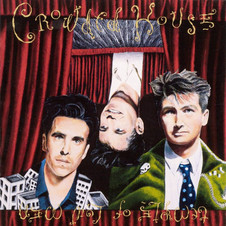

The debut self-titled album from Crowded House, produced by Mitchell Froom (Capitol, 1986).

Recording ‘Now We’re Getting Somewhere’ for the first Crowded House LP was a similar highpoint; ironically it’s the one track on which Nick Seymour and Paul Hester don’t appear. It was early days for the band, says Froom, and “a shuffle feel is the hardest thing for a band to play.” Rather than ditch the song, he decided to try it with two session players, Jim Keltner (who drummed for John Lennon in the 70s) and bassist Jerry Scheff (Elvis Presley, Elvis Costello).

“It was a real touchy moment, but Jim said something like it reminded him of Lennon, and Neil loved that.” On one of the first takes Neil improvised the whole end, the screaming, melody and lyrics. “It was a new groove for him to play and it felt really good. Ironically because of that I think Nick and Paul were a bit depressed that they couldn’t get it. But the next song they did was ‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’ and they played it really sadly, beautifully. That helped the song quite a bit – it might have been too anxious or had too much energy, but this was a beautiful performance.”

But ‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’ wasn’t Froom’s hit pick for Crowded House. “I always thought ‘Something So Strong’ was the one, and ‘The World Where You Live’. Crowded House was the second band I ever recorded, and I heard a demo with Neil singing ‘Don’t Dream’ with just guitar – that just about every producer in town had turned down. I just couldn’t believe it. The things people get excited about are so incredibly bad.”

Temple of Low Men, the second album from Crowded House, produced by Mitchell Froom (Capitol, 1988).

Froom prefers the second Crowded House album. “I think Neil comes out more, the band plays better and the songs are better. People say Temple Of Low Men would have sold more if the songs were better, but personally on the first album I think about two or three songs were lost in the translation. I listen to them and they just missed the boat.

“People have the idea that the second record was a misery and the first was joy. The first was hell and the second was joy. With the first we were trying to work out what the band should sound like. More electronic? Like Talking Heads? Pet Shop Boys? How to approach it?”

Froom has made his reputation as a producer giving groups with traditional musical values a contemporary sound; acts such as the Bangles, Del Fuegos, Bo Deans, plus the work he’s done with T-Bone Burnett, Los Lobos and Elvis Costello. “That year in which ‘La Bamba’ and ‘Something So Strong’ were big hits was just a fluke, but in general the type of music I work with might be related to singer/songwriters like the Beatles: good songs done simply and well. But still they have the notion that there’s a crazy guy in the studio that wants to try out something outrageous. But that’s about 15 percent of what sells nowadays. It used to be the whole thing.”

Recently Froom worked on the songs Elvis Costello recorded with Paul McCartney (released on Flowers in the Dirt later in 1989). “Elvis had wanted the songs to sound very early 60s – really raw. So they sent me these songs and said, ‘Paul doesn’t want it to sound like a retro record – you want to work on them?’ They were great songs, there is definitely something better about them.”

Talking production, Froom says Costello could be one of the great producers – “he really is full of music” – and that the role George Martin played in the Beatles “can’t be overstated. All the classical influences and the understanding of harmony. If I listen to Rubber Soul and the way they do a guitar overdub, or put a harmony line an octave higher – it’s very much a classically orchestrated idea. The mind behind it isn’t just one of ‘Oh, I’ll just play along.’

“Though I must admit, having worked with Paul, he’s probably the most natural musician I’ve ever met. Honest, his bass playing is staggering. It’s as though he understands everything there is to be understood about harmony. But the one guy Paul McCartney would hold in high esteem is George Martin.”

Froom has expressed admiration for the role Brian Jones had in the Rolling Stones: being experimental, adding musical colours to simple pop songs. He collects old keyboards and has a myriad of unusual instruments at his home studio. “One thing I was curious about working with Paul McCartney was how did the Beatles start [experimenting]? He said it was because at EMI there were like 12 grand pianos sitting in a room, and a closet full of all sorts of weird instruments. And they’d say, here’s 12 grand pianos, let’s hit a chord on all 12 of them. They had that spirit, and the tools were there.

“You come to a studio now, and what’s there? A piano. And musicians don’t think about experimenting, either. They think, oh I’m going to play my guitar today. Jones was prepared to pick up anything and make a noise out of it.”

The fan in Froom is quick to emerge, so it’s no wonder that when he gets together with Neil Finn the results have echoed their heroes. “I was talking to Neil about it, and he never knew what rhythm and blues or early rock ’n’ roll was. He thought the Beatles invented rhythm and blues. But I think people can be much more interesting when they don’t hear the authentic thing ’til later. Because a lot of people, when they hear something authentic, they just ignore it or copy it exactly.”

“I’M Real GRATEFUL I WAS NEVER SUCCESSFUL EARLY ON, BECAUSE WHO KNOWS WHERE I’D BE RIGHT NOW.”

Froom himself comes from a classical background. He studied piano and pipe organ, and played in rock bands around the San Francisco Bay Area during his teens. “Really miserable stuff, but you have to learn somewhere. I wasn’t one of those people who was brilliant right from the start – I mean, Stevie Winwood at 17 singing ‘Gimme Some Lovin’! All the stuff I was involved with until my late 20s was really miserable. I couldn’t figure out how to put together all the things I’d learnt. So I’m real grateful that I was never successful early on, because who knows where I’d be right now.”

“To be honest, I think producers ruin records. I’d prefer hearing records just with the band, if they were hitting their straps. You hear over and over again about the charm of demos and what’s lost with the end results. A producer’s job is just to make sure every moment on the record works, rhythmically, melodically, that there are no dead spots in the songs, and obviously to get as good a performance as you can. And that everything makes sense, there’s nothing superfluous about it. That gets under my skin. There’s a lot to worry about.”

Hearing Froom’s organ playing, T-Bone Burnett hired him to play on albums by Marshall Crenshaw, the Bo Deans, Peter Case and Costello, which led to Froom’s own career as a producer. Working with legends such as McCartney and Thompson is like a dream come true, he says, but one you can’t think about. “It’s great, but the reality of it is you listen to the music and figure out what the problems are, so you worry about it all the time.

While he’s worrying about others’ work, Froom’s own music is on hold. After finishing a Pat McLaughlin LP he is scheduled to produce the Pretenders. “It should work out – there’s a couple of real good songs and she’s got a band, so it’ll be real, probably pretty garage-y, like the original stuff.”

And late this year, work will begin on the third Crowded House album [Woodface, 1991]. “Producers produce music about as long as an artist, so while people are interested I’ll keep doing it. When you have a certain amount of success people come around and tell you you’re great and it’s gonna be forever and all that. You can’t think like that – just one step at a time.”

--

First published as ‘Spirited Harmonies’ in Rip It Up, June 1989