Dave Dobbyn's role as a cultural taonga is so deeply embedded now that it's almost shocking to recall that nearly 30 years ago he was being formally held responsible for New Zealand's worst civil disturbance since the 1930s: the 1984 Queen Street riot.

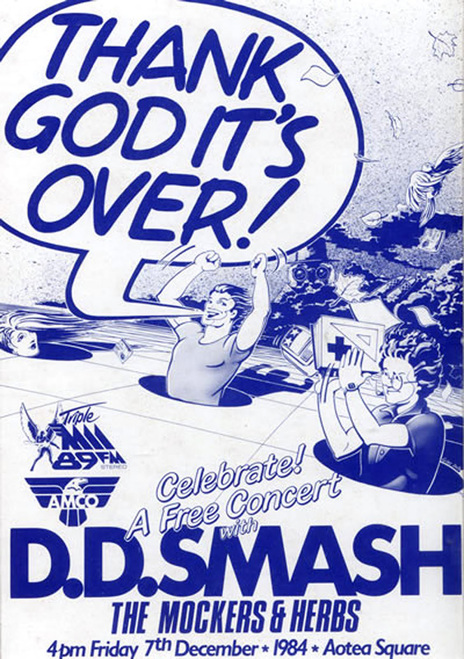

On December 7 of that year, Triple M 89FM, then the operator of a new FM radio licence in Auckland and pitching itself as a new kind of station for real music fans, staged a free concert in Aotea Square. Everything seemed to bode well. School was out (hence the name of the show: Thank God It’s Over) and the weather was lovely. When Herbs opened with a sunny set of their own, everything seemed set for a great day.

DD Smash pre-show: a short-lived lineup from 1984, in which Dobbyn and Warren were joined by Australian session players. - Photo by Murray Cammick

A few hours later, Queen Street was in bits, the country was in shock and Dave Dobbyn was in trouble.

As Rip It Up's deputy editor, I had turned up expecting to review the show. I watched Herbs and The Mockers, popped into the backstage bar, where everyone was in a good mood, then went back out front to watch the headliners, DD Smash – Dave's band.

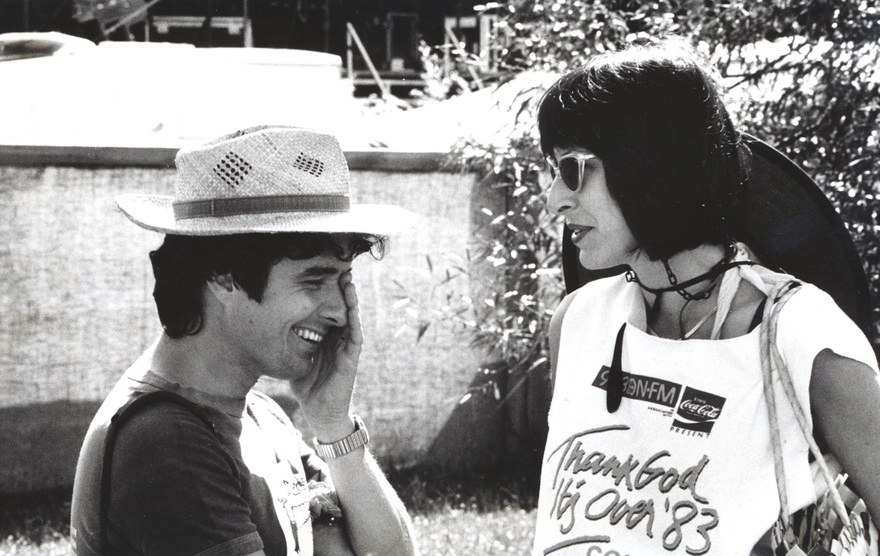

Backstage - Murray Cammick with Willie Jeffery. Murray is laughing at the '83 on the T-shirt

Dave McArtney, Andrew Boak (No Tag, 89FM), Harry Lyon backstage - Photo by Bryan Staff

Mushroom Records NZ staff: Bridget Delauney, Debbie Harwood, Debbie Mains with Mike Chunn behind - Photo by Bryan Staff

The author, on the left, backstage pre-riot - Photo by Bryan Staff

Dilworth Karaka and Fred Faleauto of Herbs backstage in Aotea Square, 1984 - Photo by Bryan Staff

The set didn't start well. The power failed during the first song, around 7.30pm. Peter "Rooda" Warren came down to the front of the stage to chat to fans while the problem was fixed. About 40 minutes later, there was a second stoppage – this one at the order of police – and then the riot.

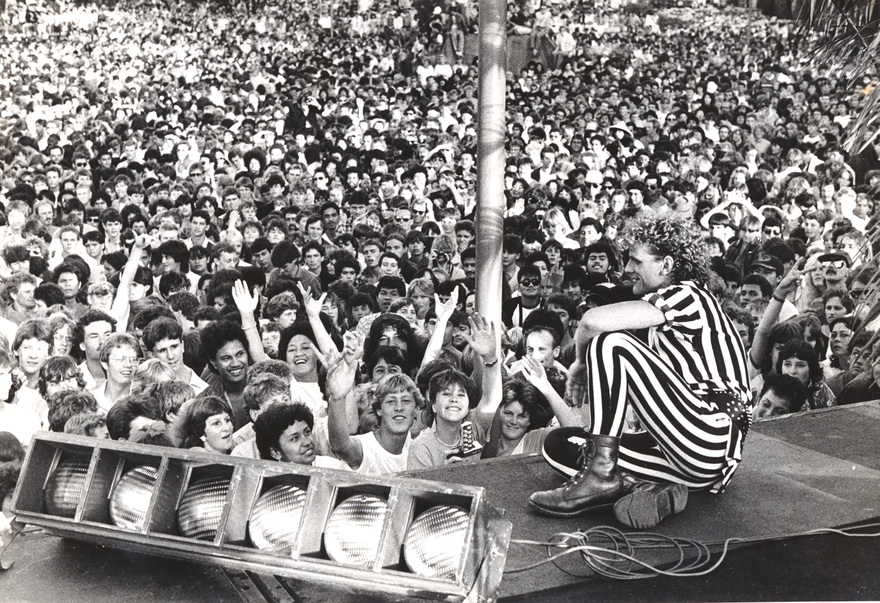

Peter 'Rooda' Warren from DD Smash talks to the peaceful crowd during the power failure - Photo by Bryan Staff

During the first break, a couple of drunkards had clambered up onto the covered walk by the Wellesley Street Post Office and urinated and dropped bottles on passers-by. When police officers arrested those responsible, they were obstructed by bystanders – and a fateful decision was made to send in a team of officers in riot gear. Anyone born in the last 35 years will probably not have seen police officers dressed this way. But at the time, the shields, helmets and batons were familiar to everyone as a legacy of the 1981 Springbok tour. For many New Zealanders, they were deeply negative symbols.

Aotea Square pre-gig - Photo by Bryan Staff

The police team lined up on Queen Street, across the only exit from a crowded square. They attracted the attention not only of the crowd, but the singer. Dave Dobbyn uttered a sentence he will regret for the rest of his life: "I wish those riot squad guys would stop wanking and put their little batons away."

The words were captured on a tape recording being made by Ron Kane, an amiable American obsessed with New Zealand music. The same tape provided me with a remarkable record of what happened next. I don't think I can do any better than repeat what I wrote then (reporting in Rip It Up in 1984):

"Where are they?" a bystander can be heard saying.

"We can take care of ourselves, it's alright," Dobbyn says later in the song; and then later, realising that the crowd's attention is beginning to shift away from the stage: "C'mon, you gotta do something here. Oh, forget about that, let's just get into the music."

Crowd noise then makes a definite shift from jeering back to cheering and clapping for the band.

"One more sentimental song and then we'll rock out," Dobbyn says before the band goes into 'Stay'. The words take on a rather grim irony a few minutes later.

"Sorry, this is just too uncontrollable … sorry, we've got to stop," says Dobbyn after the song.

Triple M's Fred Botica is up at the mic almost immediately: "We've been asked by the police to stop the concert."

Noise begins among the crowd again: "What'll happen to all this energy?" a crowd member says. "They're getting the long batons out – shit."

The sounds of jeering became louder, breaking glass can be heard. Each major impact is followed by a loud cheer.

"It's their bloody fault!" comes an exasperated young woman's voice. Other voices as the crowd moves are more puzzled than worried.

A drunken-sounding voice wanders in and out of range: "Arseholes … bastards …"

One woman screams, then shortly after comes the voice of what sounds like a young teen: "Hey … we might get on TV!"

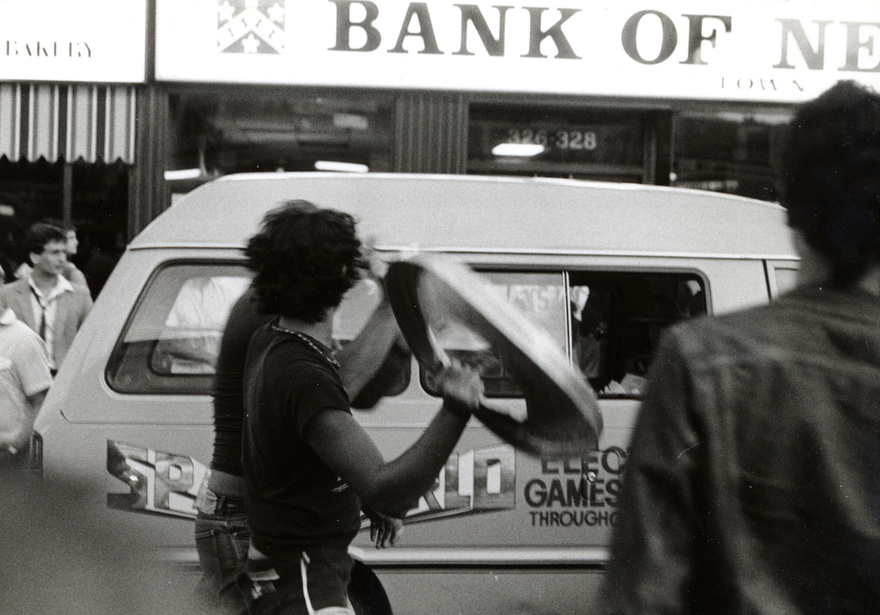

Rioting outside the Town Hall branch of the BNZ - Photo by Bryan Staff

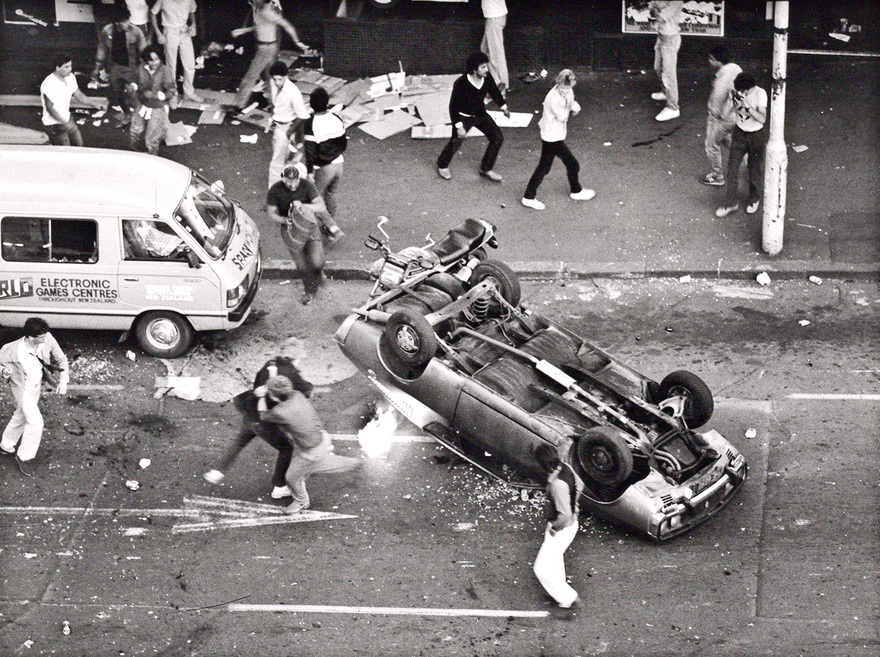

Out on Queen Street, it quickly became clear that the police had made a terrible error in blocking the only exit before stopping the show. The line of riot police was driven back beyond the Wellesley Street intersection. One group of youths began throwing missiles at the police line. Others began attacking the surrounding buildings with a spooky sense of purpose. Still others stood back and cheered each time a rubbish bin was hurled at the six-metre windows of the empty-since-it-was-built Development Finance Corporation building.

A young Wendyl Nissen later reported for the Auckland Star an atmosphere of terror among bystanders, but my experience was quite different. I walked up behind the front line of youths, in my shorts and jandals, without any real sense of fear – until the police charged, when everyone turned and ran. That was frightening. The police fell back, then charged again. This time, I lost a jandal in the retreat and had to hop, urgently, around a carpet of broken glass. I retrieved my jandal, looked around to see a fire flickering in the wrecked information centre at the corner of the square and decided it was time to go.

- Photo by Bryan Staff

I walked back along Elliott Street to the old Rip It Up offices where I was met by the editor, Murray Cammick.

"Well," he said, "You've got your story now."

I did. Outside, the police were about to make yet another terrible decision by forcing the crowd down Queen Street, where dozens more shops (including a gun store) were smashed and looted. I walked back up Wakefield Street to get my car to go to a gig at the Windsor Castle. The really sad part of the rioting had begun. Kids ran laughing from a wrecked lunchbar, carrying drinks and cigarettes.

The Auckland Visitors Bureau in Aotea Square - Photo by Bryan Staff

Meanwhile, Murray and Ron Kane set out for a long-planned 10th anniversary party for Split Enz at the Albany property of their promoter Ian Magan. The news of the riot beat them there, and as music business people arrived – some direct from Aotea Square – security staff for the guest of honour, Prime Minister David Lange, were very visible. But Lange himself never arrived. He had decided to skip the party and joined his old friend and colleague, Mayor Cath Tizard, at the Auckland Town Hall.

Ripper Records' Bryan Staff (top right) taking photos in Queen Street - Photo by Bruce Jarvis

Meanwhile, the atmosphere at Triple M, at the top of Wakefield Street, had swung from joy to dread. The event that was supposed to cement the city's affection for the station had become a disaster. Night-time hosts were told to avoid playing anything that might be seen as a reference to events. It's a safe bet that Nick Lowe's 'I Love the Sound of Breaking Glass' did not get an airing that night.

By the following day, the street was clean and Centrepoint Fabrics was advertising a "Riot Sale" across its restored front windows. But for a time, it seemed the riot might have serious repercussions for the music industry itself. Days before, there had been trouble outside a Deep Purple concert at Western Springs. Now, Cath Tizard's council found itself under pressure to ban concerts from all council-owned venues. Planned shows by Neil Young (Mt Smart Stadium), Spandau Ballet and Culture Club (both Western Springs) were threatened.

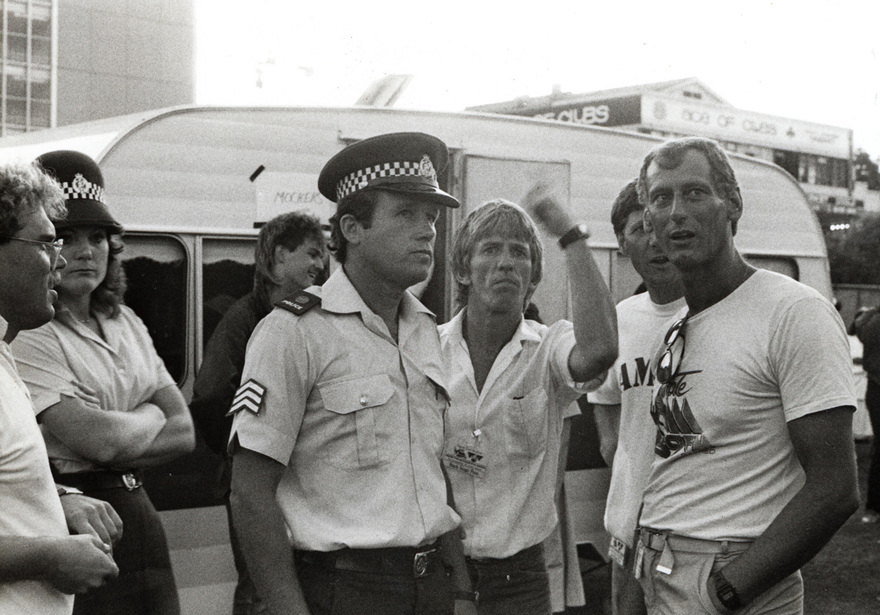

The police with clearly worried 89FM staff - Keith Williams (programme director), Barrie Everard (station owner and MD) gesturing, Cliff Kinnard (MD Amco Jeans NZ, sponsors), Fred Botica on the right. The Mockers' Tim Wedde is in the background - Photo by Bryan Staff

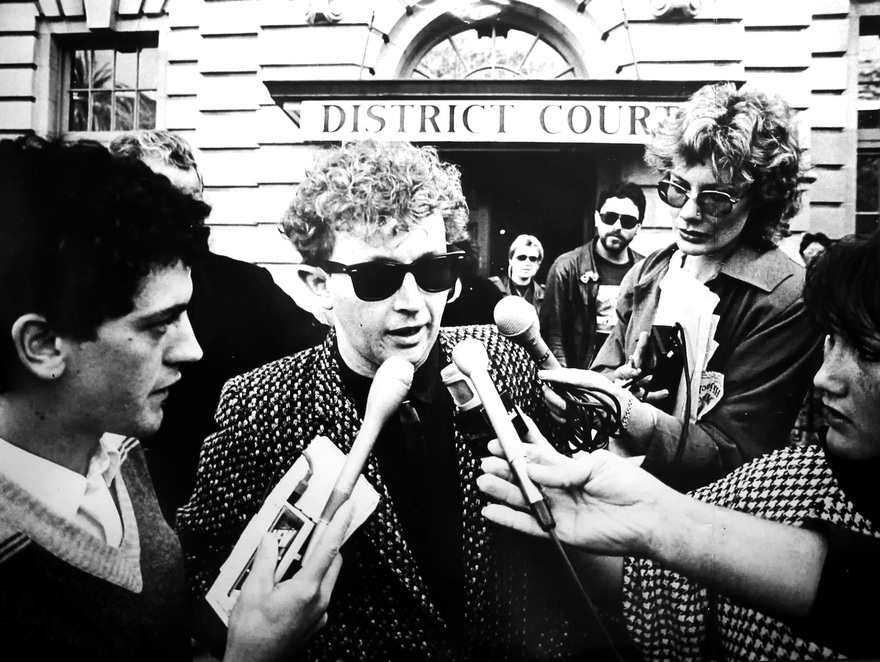

The ban was averted – but Dave Dobbyn wasn't so lucky. Unexpectedly, he was charged with behaving in a manner likely to cause violence against person or property and using insulting language. Although there were always recordings like mine that showed what he did (and didn't) say, the police presented interviews from others present putting all kinds of words in his mouth.

Dave returned to Sydney, where he was based. When I talked to him the following April, off the back of a national tour with a new band, the case was weighing heavily on him.

"I was pretty paranoid," he said, "especially playing in Auckland with the riot thing hanging over our heads. Even though we got a lot of support, it does affect you. Everyone dropping riot jokes all over the place. I'm sick to death of fucking riot jokes. But I feel better about the whole thing now. I'm looking forward to getting back in June and doing a couple of gigs."

June was, of course, the month of his trial. Defended by Peter Williams in the Auckland Magistrates Court, he was acquitted of the charges.

Dave Dobbyn leaves court. In the background is Steve Thorpe from The Mockers.

The truth was that although he said one thing he still regrets, the Queen Street riot was not Dave Dobbyn's fault. Alcohol certainly played a major part (laws on public drinking were changed as a consequence). So did an unruly public mood that had grown during the Springbok tour and brewed in the dying days of the Muldoon government.

But, overwhelmingly, the cause of the riot was a series of disastrous decisions by the police. A dark era of policing – the one of Gideon Tait's team policing units and their provocative raids on pubs where bands played – met its end in disaster. My reporting later went to the commission of inquiry on the riot, where I gather it was of interest.

Christmas of 1984, at a barbecue at my parents' place in Upper Hutt, I was talking to a senior Māori policeman, a friend of the family.

"So," my dad piped up, "Russell says you guys blew it at Aotea Square."

I cringed and inwardly cursed my father for raising it.

"Yeah," said the policeman, sadly, looking at us both. "We did."

--

Response to this feature was such that AudioCulture has published an oral history page sharing memories of those who were there: Queen Street Riot Memories.

Russell Brown reports on the 1984 Queen St riot for Rip It Up.

Shake! magazine 1988

--