The corner of Customs and Little Queen Street in mid-60s downtown Auckland, an area demolished in the early 1970s. Galaxie signage can be seen at far right.

In downtown Auckland in the mid-1960s, the Galaxie was the club of a thousand dances. Teenage workers in the CBD would flock to lunchtime gigs at the upstairs venue on the corner of Customs and Little Queen Street, and after 8pm many would return to dance until midnight. The top drawcards at the Galaxie were The PleaZers, The La De Da’s, and The Underdogs, and go-go girls would lead the latest dances: the hully gully, the watusi, the jerk, and especially the shake. The Galaxie was originally the Shiralee, where from 1962 the Embers and Ray Columbus and the Invaders drew big crowds. But by 1965 – with the Beatle Inn just around the corner – the Shiralee had lost its shine. So its proprietor Fred McMahon sold the venue to Auckland entrepreneur Eldred Stebbing, creating what would now be seen as a 360-degree music business. Stebbing had Auckland’s leading bands signed to his Zodiac label, recorded them at his Saratoga Avenue studio, and now he could offer them regular gigs, just as the teenage dance market was booming. The Galaxie opened on 11 December 1965, with the PleaZers topping the bill. Soon the crowds were lined up down the street, waiting to climb the narrow stairs to Auckland’s pop Mecca. In a few short years the venue – and location – was obliterated by the Downtown shopping centre. It is now part of Britomart transport hub. This is an extract from Wired for Sound: the Stebbing History of New Zealand Music by Grant Gillanders and Robyn Welsh (Bateman, 2019). – AudioCulture

Countdown to clubland

The Galaxie, with the Stebbing family at the helm, was always destined to be a hands-on affair. It was Margaret Stebbing who sewed yards of red gingham into table cloths and who laundered them daily. It was Vaughan Stebbing who helped his mother after school by ironing them on their commercial press at home so that Margaret could then patch the holes left by cigarette butts.

After weeks of hard work, a series of publicity countdowns appeared in the entertainment page of the Auckland Star that read: “One week to go for the grand opening of the Galaxie” ... “Only two days to go” ... “Only one day to go” ... “Tomorrow night, don’t miss it”. The Galaxie duly opened for business and The PleaZers and The Layabouts were the first two resident bands.

The PleaZers at the Galaxie opening - Grant Gillanders Collection

From the start, Eldred had wanted to create a club without alcohol that would be a safe, affordable place for young people to enjoy live music. The Galaxie itself was a world away from its understated street frontage. Inside, a small foyer with its white painted, decorative concrete block walls was home to the genial, well-built bouncer called Jerry who neatly deflected any undesirables. Those who got past him headed up stairs into the first-floor nightclub with their tickets from the cashier, who just so happened to be Tony Moan, Stebbing’s junior engineer at Saratoga Ave, who worked at the Galaxie a couple of nights a week.

The club itself fronted Customs St West and comprised two stages, two dance floors and a raised area for the DJ and his double turntables, as well as the cloakroom, ladies and gents toilets, mezzanine office and kitchen/cafeteria. The stairs led directly up to the smaller dance floor with its motorised, mirrored ceiling ball and tables and chairs. Further to the right, the main dance floor was flanked by raised cubicle seating. Eight switchable, four-colour lighting grids, along with concealed lighting underneath the seating, added to the mood and enabled the back-up bands to set up on the smaller end stage in the subdued light.

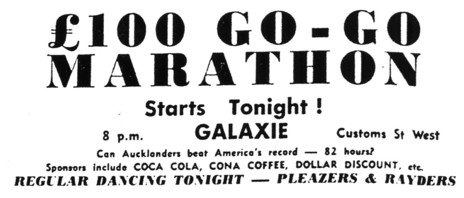

Ad for the new Galaxie Lounge opening night, 11 December 1965.

Nearby, cafeteria staff served toasted sandwiches and poured soft drinks directly into jugs for the patrons to take with their chunky tumbler glasses back to their tables. The Cona coffee machine was at the far end of the counter. Eldred’s pride and joy was his large commercial ham-slicing machine which stayed out-of-sight in the kitchen, up steps behind the counter.

In keeping with the law, alcohol was forbidden, and if anyone turned up drunk they were despatched with a tactful, “Come back when you’ve sobered up.” Robert Stebbing explains that his father Eldred “did become something of a parental figure to some of these kids. A lot of them came from broken families and he’d help them out, listen to them and offer them a bit of advice if he felt they needed it.”

The Galaxie, lemon gin and cider

The law aside, alcohol and the band members who frequented the neighbouring liquor store before their Galaxie gigs was another matter. Evan Silva, latterly a soul-funk-gospel artist, recalled his Galaxie days with his first band The Action and his pre-gig routine of taking the bus into the city from the eastern suburbs, to play from Wednesday through to Sunday nights.

“Every night there’d be other musicians from different bands on the bus – Neil Edwards, Mike Wilson, Gus Fenwick, Kim Rouch – and we’d all be heading into the city. We’d hook up on the bus on the way to the terminal and then part ways. Some would go to the Top 20 or to the Platterack, some to the Galaxie and other clubs around the town and we’d hook up again at all the parties later. We'd buy cheap lemon gin – 15/- a bottle it was – from the bottle store opposite the Galaxie. We used to sip that stuff out of our shoes. We'd then go on to perform – at times we were off our faces.

Go-go marathon competition at the Galaxie. The winner, Faye Walker, danced for 100 hours 5 minutes.

“I remember Eldred coming in at a similar time each night to oversee things at the club. I was out the front of the band so I could remember his routine. He’d stop at the top of the stairs, do a general glance then head over to the kitchen or band room to do a quick scan for approval. I remember sneaking past him on the Galaxie door a few times when I had my bottle of lemon gin under my jacket. I’m sure he knew …”

The Underdogs also pushed the bounds of behaviour. In addition to their night-time gigs, they would perform at the 12 to 2pm lunchtime session and then rush to catch the 2pm movies, either around the corner at the Oxford or a quick dash up Queen St to the other cinemas.

The boys always dressed the part of whatever movie they were going to see, as Murray Grindlay explained: “We saw Blue Max, which was about a First World War German fighter pilot. So we dressed in German air force uniforms, goggles, scarves and those leather flying hats that domed up under the chin.

“On another occasion we went to see the Oliver Reed movie The Trap, which is about a fur trapper in the north of Canada, so Lou Rawnsley made us all costumes out of fur, and that’s how we showed up at the ticket booth – all five of us standing there looking like Daniel Boone.

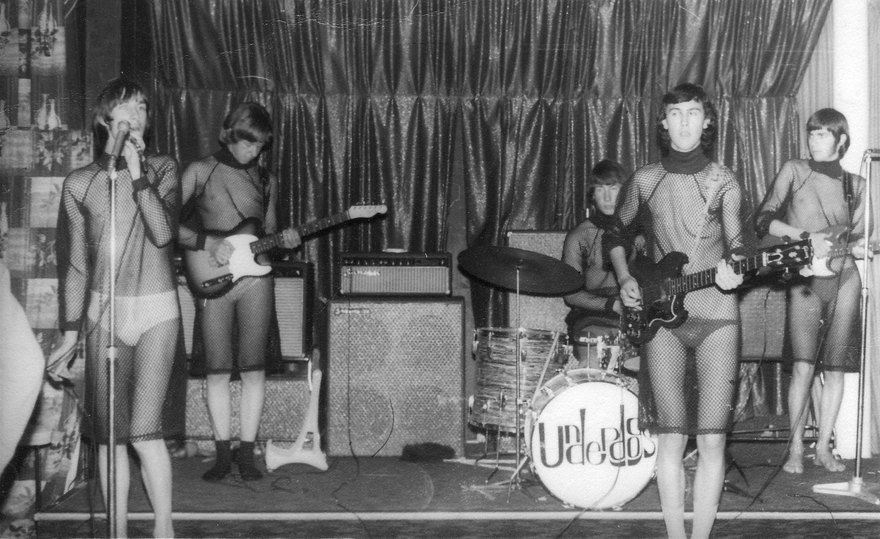

The Underdogs in their underpants at the Galaxie. Left to right, Murray Grindlay, Harvey Mann, Tony Walton, Neil Edwards, Lou Rawnsley. - Ian Thomson collection

“After the 2 o’clock pictures, we’d head back to the Galaxie and stop off at the joke shop in the Canterbury Arcade for our supply of practical joke items, stink bombs and stuff that we could throw at people from the stage. We’d then head on down to the Great Northern Hotel, across the road from the Galaxie, for a bottle of Rochdale cider. It was the cheapest booze that you could get at the time. We were so young and skinny that it didn’t take much to get us pissed – not that getting pissed was a big thing for us during this stage of our career and we didn’t have a lot of money to spend on booze anyway.

“Then it was across the road to the Galaxie to work till closing time at midnight. After the gig finished, Eldred would lock up behind him and leave us to rehearse until about 3 o’clock. We just loved our music so much and we were learning new stuff every night. It was great. We became music intellectuals and we’d sit around and dissect all of the latest sounds. As far as we were concerned, if you didn’t like the blues then you were of no use to man or beast.”

Neil Edwards would sneak his cider into the Galaxie on numerous occasions. “I would hide it behind the coat racks in the cloakroom. It was like hiding it in your wardrobe at home and, apart from the men’s toilet, it was the only place that Margaret never looked.”

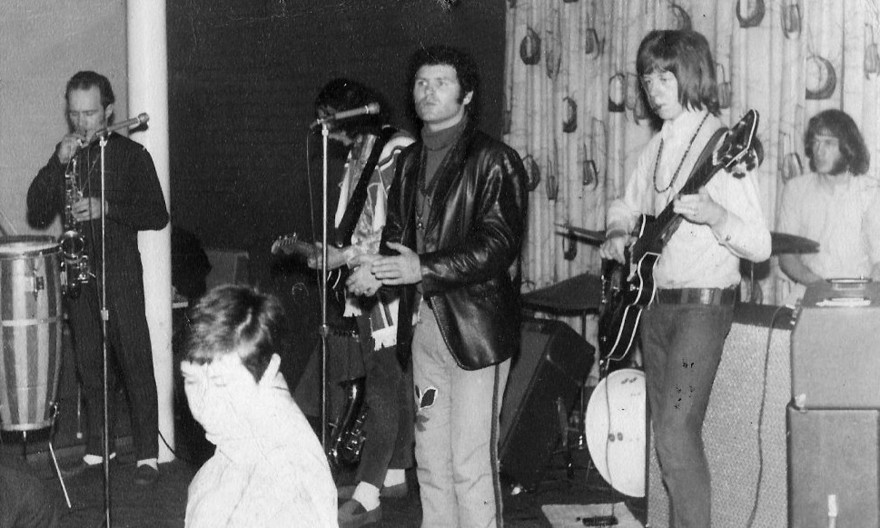

The Brew at the Galaxie, 1967. Left to right: Bob Gillett, Doug Jerebine, Tommy Ferguson, Harvey Mann, Ian Thomson. - Ian Thomson collection

As a live music venue, the Galaxie was a winner. It ran six nights a week from Monday to Saturday with lunchtime gigs that initially featured bands, but which later used jukebox entertainment instead. Sunday afternoons were reserved for the young teenagers.

For the Stebbings, juggling the recording studio and the Galaxie’s commitments was a tough act. Margaret’s responsibilities included managing the studios. During the day she did so when Vaughan, their youngest son, was at primary school. Robert managed the Galaxie on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday nights, with Eldred, or Margaret, and Robert there on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. Robert’s other commitments included outsourcing the lunchtime catering that had to be fitted around his tertiary electrical engineering and telecommunication studies.

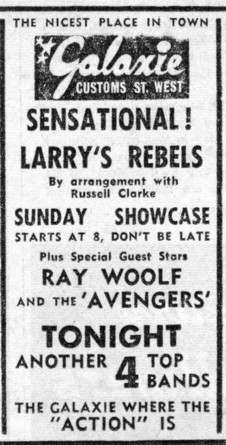

Larry's Rebels, Ray Woolf with the Avengers, the Galaxie, 1967.

Meanwhile Eldred was busy recording, managing and touring his bands and battling interminably to get his artists’ records played on the state radio stations. But if he thought that performing at the Galaxie would help secure them more airtime, then he was wrong. It was a long time before he found out why.

“They were a pack of wags at Broadcasting House. Some weeks I’d have two or three new releases and I’d personally go and see the programming manager and give him copies of the new releases. He’d say, ‘Oh, great, thanks a lot. Don’t worry about a thing. I’ll make sure that they get played,’ but he never did.” Eldred later learned that when the manager retired, the old carpet in his office was ripped up for replacement and a great number of local records were discovered underneath. At the time though, his frustrations required some creative alternatives.

Promotions, the Galaxie newsletter and the Go Show

Eldred produced a monthly four-page Galaxie newsletter which served as a gig guide, complete with profiles of the Galaxie bands. He also paid for air time for the Galaxie’s own 30-minute radio programme called the Go Show, which was broadcast on 1ZB every Saturday morning with DJ Phil Shone and Galaxie compere and singer Bobby Davis.

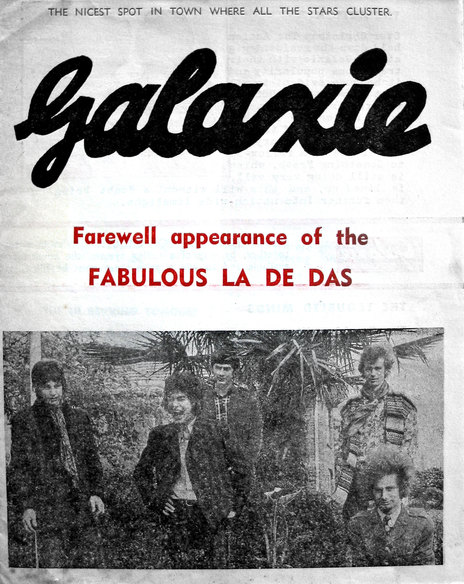

The Galaxie nightclub newsletter the week The La De Da's left for Australia, 1967.

For the PleaZers, who had been banned from the airwaves after their behaviour on the TV show New Faces, the Go Show was their only chance for radio exposure in the days of state broadcasting before Radio Hauraki went to air in December 1966.

The show was recorded at the Saratoga Ave studio with more than 50 percent of its music drawn from the Zodiac and Philips catalogues and the rest from various HMV releases. Advertising content featured the Galaxie’s forthcoming attractions and special guests.

Engineer Tony Moan worked through the pressure of those production deadlines. “The show was recorded live-to-tape and delivered to 1ZB for broadcast. There was little or no editing or post-production, so for 30 minutes I’d have one hand lining up the records while the other hand was cueing up the tape decks for the ads and various sound effects. It was a bit like flying by the seat of your pants really. If I made a mistake with the cues then we’d have to go back and start again from the top.”

In September 1966 the New Zealand Top 10 was broadcast live from the Galaxie. In the shiny suit is host Peter Sinclair, with local drummer Alex Behrens. At the back, from left: Roger Wiles from The Gremlins, NZBC radio producer Johnny Douglas, and Ben Grubb, Peter Davies, Paddy McAneney and Glyn Tucker, all from The Gremlins. Kevin Borich from the La De Da’s is obscured on the right. - Johnny Douglas collection

Eldred’s approach to the running of the Galaxie paid dividends from an unexpected quarter that first year. Word had got back to the parents of the well-to-do girls about town that the Galaxie was the place in town for a reputable “do”. That was sufficient for the heads of the Diocesan School for Girls to allow the annual ball to be held there, even if the venue was at the seedier end of town. The rules were clear. Any patron not property attired – and that included wearing a tie – would be told to go home and change. Then the Galaxie would be happy to receive them back as a guest.

The police were regular visitors to the Galaxie although rarely, if ever, on official business. Those on the beat regularly called in for a free cup of coffee or a chat with the staff and it all added to a relaxed vibe in the area. Robert recalled the vitality. “The whole area came alive after the Galaxie opened. We quadrupled the patronage from the Shiralee days, the bands all socialised together and they’d often head out to the Oxford picture theatre too. Margaret’s red Fiat Bambina that Eldred often drove was parked outside the club most nights. One night Eldred came out to find the Bambina sitting on the roof of the underground public toilets across the road. It was just a good bit of harmless fun.”

By the late 1960s, significant changes in New Zealand society were starting to take shape. Moves had been afoot throughout the decade to relax the sale of liquor laws and by 1967 the old days of “6 o’clock closing” had given way to 10pm closing times. The ramifications for the hospitality industry were significant, but Eldred wasn’t interested in getting involved in any of it. He’d had two hectic years running both his studio and the Galaxie. He had also learned of plans to demolish the Galaxie building to make way for the new Downtown shopping centre. Besides, he had his own plans for a purpose-built studio complex. Amid all of this, the success of the Galaxie had not gone unnoticed by Fred McMahon. By early September, Fred was back as manager at least, according to one newspaper report. Whether or not he was the new owner then was not confirmed.

Eldred recalled the timing slightly differently. “Before we took over the club and renamed it, they’d have been lucky to get 40 people in there on a Saturday night. We were constantly getting up to 800 people. Fred was asking if he could buy the club back so at the end of 1967 I let him have it.” He did so having built an enduring fan base.

--

An excerpt from Wired for Sound: the Stebbing History of New Zealand Music by Grant Gillanders and Robyn Welsh (Bateman, 2019).