On 19 July 1985, Radio With Pictures filmed a "reggae special" at Victoria University's Union Hall, in conjunction with Radio Active. The bands were Aotearoa, Dread Beat & Blood, and Herbs. Ten months later, with the addition of Ardijah to the bill, this groundbreaking event became a national tour. The 1985 TV special can be viewed above.

Wellington, 1987: Heads turn when Aotearoa strike up their rendition of Nina Simone’s ‘Young, Gifted and Black’. Ngahiwi Apanui, the Wellington band’s ebullient songwriter, grins. “A lot of Pākehā people shit themselves when they hear it!” he says. “They’re dancing and they stop!

“It’s amazing how a song easily accepted in the 60s can stir such emotion in New Zealand now. But of all the songs written to inspire young black people, that one says it all. Black people don’t look at themselves as being talented. It’s a self-esteem thing. But all of a sudden you’re being told you’re young, gifted and Black – and you go, Wow!”

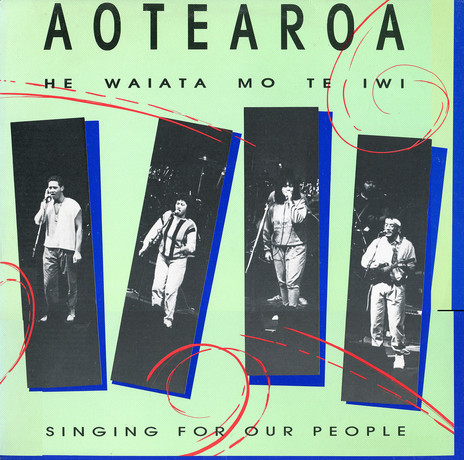

‘Young, Gifted and Black’ is the only cover version on Aotearoa’s second album, He Waiata Mo Te Iwi, (“Singing For Our People”). Apart from a Joy Yates/Dave MacRae number all the songs are written by Apanui. It’s a bilingual album sung in English and te reo Māori. Aotearoa’s aim is to awaken young Māori to their own spiritual resources. Led by the determined Apanui, they are a dedicated political band.

Aotearoa LP cover, He Waiata Mo Te Iwi (Jayrem, 1987).

“Heaps of Pākehā musicians say. ‘Your stuff is political, you’re pushing this stuff on us,’” says Apanui. “And I say, ‘Look. Everything that you sing about, what you wear, the way you look, the language you speak, reflects where you’ve come from, where your people are at. So don’t tell me I haven’t the right to do that as well.’”

Apanui formed Aotearoa in 1984 after meeting his friend Joe Williams at Victoria University’s Te Herenga Waka marae. The purpose he says, was to make “Māori culture and Māori cosmos and being Māori acceptable to young Māori people.”

“My first idea was to have a group singing totally in Māori. After a while it became obvious that there was a whole section of Māoridom that would miss out on what we do if we didn’t sing in English as well.”

Since the days of the band’s first single ‘Maranga Ake Ai’ the composition of the group has changed as members have come and gone – so maintaining the original concept has been difficult. “In the beginning we had people who knew everything about what we were doing intimately. Now the band is more typical of Māori youth, with varying degrees of knowledge of things Māori. It’s been hard to get them past this thing that it wasn’t the music that was the most important thing, but the concept.”

Implicit in adhering to that concept is an understanding – and belief – in the spiritual side of “being Māori”.

“There are a lot of spiritual forces at work which can either punish you or support you. The concept that we carry, the kaupapa, is very dangerous and a lot of people shy away from it. People say you can get stung by it.”

Apanui talks of “timely little reminders” to do things correctly, or with the right motive. “Things like visitations. I’ve seen it happen. There are times when I’ve felt under threat. When I’ve woken up in the middle of the night and I’ve been fighting with something that’s just about given me a hiding …

“For me the concept of the band is something totally Māori, and therefore deserves everybody’s total respect. It has to for the music to come out convincingly.”

Aotearoa, 1987. At the back: Jon Wrigley, bass. In front, L-R: Kerry Noda, keyboards; Maaka McGregor, drums; Ngahiwi Apanui, guitar, vocals; Mike Morais, manager; Karl Smith, vocals; Ngapera Hoerara, vocals. Absent: Kevin Hotu, guitar. - Tu Tangata, June 1987

He Waiata Mo Te Iwi is a consistent album, with superb singing and musicianship on many fine songs. The vocals are confident, with lovely harmonies. “Māori have always got this thing for melody,” says Apanui. “They love melody, heaps and heaps of it! …

“Māori songwriting has always been totally different to English songwriting, because the emotions that are evoked in Māori songs are very deep ones. Māori have very, very deep emotions. Go to a tangi and they just sob – they call that ‘e hotu hotu manawa’ – your heart sobs, it really does, it really hurts.

“It’s the same when you get angry, so pissed off you can’t hold it. Young people today are probably more angry than 20 or 30 years ago. They’re angry because they feel they’ve missed out on something, something they felt would have made them whole. It’s made them feel like, ‘I’ve wasted 20 years of my life and finally discovered what I am.’”

So now it’s a matter of “overturning conditioning”. While the album has traditional elements such as the opening song of welcome ‘He Waiata Pōwhiri’ or the timeless melodies of ‘Sweet Child’ and ‘E Hine’, the influence of reggae is still very strong. Apanui, however, believes that Rastafarianism doesn’t fit in with “being Māori.”

“We’re using reggae and rock and soul and funk to put across these messages they’re familiar with.”

“We take what the English press call ‘a modernistic approach’. We use methods that are familiar to people to put across our messages. If our whole concert consisted of two hours of waiata they wouldn’t know what we are talking about, basically because they’re not familiar with it.

“We’re using reggae and rock and soul and funk to put across these messages they’re familiar with. We sort out which medium is going to suit best the theme of the song, and reggae has become the Black political music. So because a lot of our songs are politically motivated we’ve used reggae – and have become known as a reggae band rather than a Māori band.”

To this writer, a “Māori band” usually means strong singing and exquisite playing, from Herbs to any small town pub band, and Aotearoa’s album reflects this. However Apanui is aware of the negative stereotypes as well. “The words ‘Māori band’ have always had negative connotations, but for me it’s now. What it actually means is a band based on things Māori.

“The problem is that Māori musicians have been at a disadvantage – not talentwise – but because there’s a heap of stereotypes about what they do and their attitudes. I know several bands that have been really good but have been ignored, so after three or four years bashing their heads against the wall they give up. So then it’s ‘Oh, a typical Māori band, breaking up, no stickability.’ That would kill most bands.

“Golden Harvest, with Karl Gordon out front, were great. Then he left, and no one took any notice of them after that, because they were all Māori. The same with Taste of Bounty down here. They were a great band. Hori and Hemi were good too, they were the same as we are about.

“When I started this band I thought there’s no way we’re going to be ignored because it’s gonna scare the shit out of everyone. Sure enough our strength – what’s made us noticed and newsworthy – is what we’ve been singing about. People said, ‘You won’t get exposure, they won’t listen to a Māori political band.’ And I said, you just watch ...

But, says Apanui, it’s much harder to run a band with a political attitude than one which just wants to entertain. “You tend to take a lot of flak, people yelling ‘Get off!’ or ‘You don’t know fuck all about the country!’ People think singing about politics is a load of crap, but everything you do on a stage is political! You dress and play in a certain way and people think, ‘oh wow, that looks really cool. I’d like to dress like that.’ Music is put up as a kind of fantasy world, so it’s a powerful medium to put across messages.”

The album contains songs such as ‘Positive’ and ‘Singing for Our People’ that are the assertive voice of the Māori renaissance, plus the supportive ‘Kanaky People’, which urges unity among the people of the Pacific. “The Kanaky case really sticks out in the Pacific at the moment. A lot of Māori people feel it’s wrong to pull together, but Māori people are preoccupied with surviving. Any time they get to put in Māoritanga is a bonus. There’s a divide-and-rule mentality of administration in the Pacific ... Out of all the people in the Pacific, we’re the most closely related.

“Herbs started off with a kaupapa that was about Pacific unity, with the combination of all these Pacific influences. [At first] I thought they were just another reggae band, like country and western singers, singing about Tennessee. But I was dragged along and thought, Wow – these guys are neat. I was so inspired. I thought if we do reggae, we’re gonna do New Zealand reggae, which is Herbs. Funny thing is, our first single ‘Maranga’ was Herbsy, but the recent stuff is very UB40 – and I don’t know how that happened!”

Herbs, Ardijah, Dread Beat & Blood, and Aotearoa, assembled onstage at Whangarei, 29 July 1986. The national tour featuring all four bands was promoted by Hugh Lynn. Ngahiwi Apanui is third from right, with a white headband. - Simon Lynch Collection

Apanui is quick to acknowledge Herbs’ role as the leaders of contemporary Māori music.

“They started everything, there’s no doubt about that. They’re looked at as being the Black band in New Zealand. That band is loved. Maybe the younger ones have got bored with them, saying they’ve become commercial. But after six years of bashing their head against a wall they deserve it, I think. Their talent demands it. Them singing with Dave Dobbyn to tell everybody they’re good – I already knew that!”

Aotearoa’s LP is to be released in Britain in August [1987]. Last year the band won a Commonwealth Youth Secretariat award, for services to Māori youth. It’s the first time a band has won such an award, and Apanui is particularly proud of it as it’s a reflection from “outside our people” of their impact. The band is yet to actually receive the award: Prince Andrew was supposed to do the presentation ...

“I thought, what! We’ll get our arses kicked! For us to accept it from an institution that for so long has been responsible for the way we are would have been wrong. And political suicide. So I said to Internal Affairs, No way. The symbolism is too strong. It goes against everything we stand for. We said we’ll take it off two people – the Māori Queen or [Prime Minister David] Lange. They went away for a while and came back and said, ‘What about Peter Tapsell [the Minister of the Arts, a Māori]?’ I said, okay, anyone, as long as we get the thing ...”

Apart from the medallions for the band members (“Wow”) the award means two of them can travel overseas to any Commonwealth country. “So we’re going to Canada to study the Indian people. Their situation is really peculiar – it’s a bilingual country, but their language isn’t recognised. Then we’ll go to Britain to look at studio techniques, what young people are doing, and to Wales, where the parallels are so similar to here.”

Aotearoa, from Rip It Up, April 1987. Ngahiwi Apanui is second from right; Joe Williams is on the far left.

In Wales, the recognition of Gaelic as an official language has meant the survival of the language (a Gaelic television channel recently filmed Aotearoa in concert) and the introduction of Māori media such as radio stations and a television channel is seen by many to be equally essential here. Apanui, although he’s been involved in short term Māori radio projects, is hesitant: “It’ll give commercial radio programmers more excuses not to play Māori music.” However, say the Māori radio lobbyists. Māori music isn’t being played now, so there’s nothing to lose.

But Apanui doesn’t want another ghetto like the Polynesian prize at the New Zealand Music Awards. “Herbs’ Long Ago was the best album to come out that year by a long shot. Instead, it got the darkies’ consolation prize. To not even be judged by your peers. It was a joke.”

Frustration is understandable. Aotearoa’s sweet ballad ‘E Hine’ was purposely aimed at commercial radio, but Apanui knew it wouldn’t be played because it’s in Māori – despite foreign language pop such as Falco and ‘99 Luft Balloons’ receiving airplay here.

“Oh well, I thought, here we go, shall I bash the radio stations again on Te Karere?” he says. “It struck home when ‘Poi E’ wasn’t played: the reason was that it was in Māori, and a lot of people were frightened by the resurgence in Māori things. “What’s there to be frightened of? The more that an urge to be resurgent is repressed the more that it’ll turn into violence, and I don’t think a lot of people realise that.”

In the meantime, the status quo remains. Radio continues to ignore local music, or wait until they’ve been accepted overseas. An indigenous music is growing, however – at home in Aotearoa.

--

First published as “He Waiata Mo Te Iwi Aotearoa: Singing For Our People”, Rip It Up, April 1987.

Read more: Herbs, Aotearoa, Dread Beat & Blood, and Ardijah, on tour 1986