Peter Needham: “Mick Jagger bought us a beer!”

I first met Arthur while working in Wellington for the NZ Listener. I started there in 1968 as a sort of cadet/copy boy/writer, fresh out of Naenae College, and was delighted to begin my first job in such a creative environment. I got on well with fellow writer Arthur, who was a couple of years older than me and more experienced (these things count when you are 18!).

The Listener was a talented place – names I remember from the time when Arthur and I worked there include editor Alexander MacLeod, Noel Hilliard, Ray Knox, Larry Pruden, Philip Temple, Alex Fry, Rob Keyzer, Jill McCracken, Pauline Swain, Cameron Hill and David McGill – as well as sub-editors Noeline Myers and Tom McWilliams, photographer Bill Beavis, and George Barrett, who handled the commercial side.

Arthur became an ally and a good friend – a fine writer with dry sense of humour and a wide knowledge of music. We flatted together for a time in a big old weatherboard house. Arthur had a lot of tolerance – I was a bit erratic and not the world’s easiest flatmate.

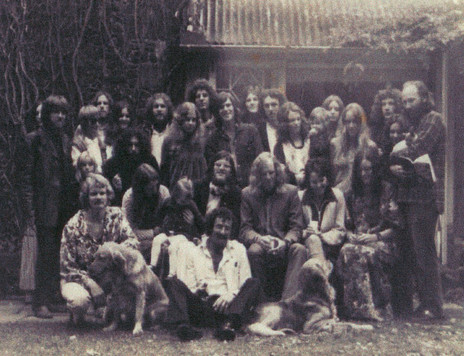

Auckland journalists out in force for a Joe Cocker press conference at the Hotel Intercontinental, 5 October 1972. Seated in the second row on the right are Arthur Baysting and Terence Hogan. Phil Gifford is in the centre, at the aisle, with moustache. At left, Ray Columbus and Neil Roberts. In the front row, with head down, is journalist and blues guitarist Alan Young. At the far right is Auckland Star columnist Michael Brett. Standing at the back, centre right, in horn-rim glasses, is Ian Magan. - Photo by Bruce Jarvis, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1704-0820B-13

Early in 1973, the Rolling Stones visited New Zealand to play at Western Springs. The Listener was offered an exclusive interview with Mick Jagger. Wow! Three staff writers immediately volunteered for this assignment – and in the end, perhaps to avoid bitter disappointment, it was decided that all three should jointly interview Jagger.

So Arthur, me and Rob Keyzer headed for Auckland. We were all aged in our early-to-mid 20s. Arthur had seniority by a narrow margin. The interview took place after the concert. Jagger (who, incidentally, was aged 29 at the time) was still wearing his stage gear, an aquamarine velvet jumpsuit with silver ornamentation. Very 1970s chic. Arthur asked the best and most astute questions – mainly because he knew plenty about popular music (probably more than Rob and I combined). Arthur brought out the best in Jagger. Instead of arrogant and stroppy (as some media had portrayed the Stones’ front man), he came across as articulate, polite and intelligent.

At one point, Jagger even asked if we wanted a drink. We did – and beers duly arrived. This was significant because it was Sunday and in those days you couldn’t buy alcohol on Sundays, unless you were a guest at a hotel. Jagger met that criterion at the old Hotel InterContinental Auckland. Presumably our refreshment went on Jagger’s account.

Interview over, we headed back to Wellington to write it up. When my girlfriend of the time asked how things had gone, I replied, with as much casual nonchalance as I could muster: “Mick Jagger bought us a beer!”

Thanks Arthur!

Susy Pointon: this is an epic love story

My first sight of Arthur Baysting was a black-and-white photo of a long-haired youth in flares and wide-rimmed black spectacles, posing on a swing in some bleak Wellington playground, circa 1968. Jean Clarkson (then a dead ringer for Buffy Sainte-Marie) and myself (desperately trying to clone Pre-Raphaelite muse Jane Burden) were first-year students at Elam School of Fine Arts in the days when if you wanted to get a critique from tutor Colin McCahon you had to go hunt him down in the Kiwi pub up the hill.

Susy Pointon, late 1960s.

It turned out Jean was in love with a romantic poet (moonlighting as a cub reporter for the Listener) whom she had met during a thrill-packed visit to Wellington. He must have been impressed with her character because he turned up soon afterwards and basically has never left.

This is an epic love story. Arthur and Jean are my personal role models for functioning healthy couples. They have managed to pursue a myriad of dazzling and diverse creative adventures together over the past 50 years, as well as raising two kind, smart and well-adjusted children, and maintaining a warm and welcoming home: and all of it without subsuming each other, or losing respect for each other. They are still keen to have a laugh and a dance when the mood takes them.

Over the years I have been fortunate to share this friendship in many kitchens, many flats, many cities and many guises. I have known Arthur the poet (I still have vivid memories of he and Jean hand-setting his book of poetry in the Elam design studio), alternative press journalist, political activist, stand-up comedian, TV star, pop culture journalist (he was famously chosen to co-write the feature film Sleeping Dogs on the basis of the thoughtful review he gave Roger Donaldson and Ian Mune’s first drama Derek in 1974), documentarian (he and Jean toured the world researching alternative culture for then-producer Bob Harvey), scriptwriter, songwriter, political adviser for Helen Clark, music industry advocate, local TV content advocate, children’s advocate, cannabis legalisation lobbyist, husband, father, brother, and beloved friend of many.

His career demonstrates the skills to duck and weave needed by anyone hoping to sustain a creative career in New Zealand, but in his case it is always driven by passion and the acceptance that there will be lean times as well as fat times and you’d better enjoy the process rather than hanging out for some pay-out at the end.

And in this process Jean has never been content to be a muse (“I love your feet” – Neruda) or a handmaiden. She has always maintained a parallel career in the arts: as the designer of some landmark political posters in Australia and New Zealand, as an advocate and practitioner of Pasifika through her teaching in the fabric design department at AUT (a programme that produced a number of our current fashion luminaries), as an artist exploring the legacy of her ancestors, the women who travelled with mutineer Fletcher Christian from Tahiti to Pitcairn and later Norfolk islands, as a teacher of art to prisoners at Paremoremo and Wiri Women’s prison, as the chair of Pacific Arts Trust Tautai and as someone who can whip up a gorgeous dinner for however many eager faces that come to the door of their Grey Lynn cottage.

I have so much to thank Arthur and Jean for. For their friendship during the good times: that premiere of Sleeping Dogs at the Civic where Arthur turned up as Neville Purvis and Nevan [Rowe] and I arrived in a white Rolls-Royce; picking them up in Nashville in a long grey Cadillac to take them home to my farm in the Appalachian Mountains; the many exciting writing sessions on fabulous film scripts that didn’t get made; and the years labouring over a film history that didn’t get published. Also, the bad times: when I was literally under the gun and I called Arthur in despair from the parking lot of a Walmart in Ohio. He held the phone up to the window so I could hear a tui and a chainsaw on a Sunday afternoon in Grey Lynn to remind me that there was another reality, another sanity: the sounds of home.

Those who know Arthur and Jean will join me in treasuring the nights around that red Formica topped table in their kitchen with great music and great food and laughter, great people telling stories, making plans, being outrageous, keeping the faith. Like the tall trees in their garden sanctuary that have never been mowed down to make way for more in-fill housing, like the simple stuff Jean and I rescued from the inorganic rubbish collections to furnish our houses, like the visits from the wild birds, the eager children and other people’s pets that come to their garden seeking refuge from the anxiety and bombast of the city, it is good that some things never change. When I think of Arthur and Jean the word “patriots” comes to mind. Or maybe “cultural warriors”. Or maybe just bloody good folks.

Jan Kemp: Toitoitoi Arthur!

Though it was Murray Edmond who first invited me to read poems with him & others, when I was living in Titirangi in the late 60s and studying at Auckland University as he was, it was Arthur Baysting who first published me in book form as editor of The Young New Zealand Poets (Heinemann, 1973), after we’d all contributed to the student newspaper Craccum and the little magazines Freed and Spleen as well as a New Zealand Universities’ Arts Festival Literary Year Book.

A garden party at 2 Ayr Street, Parnell, c. 1972. Arthur Baysting is sitting in the centre, with bow tie. David Mitchell, poet, is on the grass in front of him. Jan Kemp is at the back left, the fourth visible person; on her right are writer Russell Haley and his wife Jean. The tall man two along on her left is artist Rodney Fumpston; three along from him, centre right, is graphic artist Terence Hogan; writer Barry Southam on the far right. - Jan Kemp collection

The Young New Zealand Poets was the first anthology in book form of the work of the group with whom I mostly read: 18 men and me. Although I remember a few woman poets taking part in some Auckland readings too – Eleanor Horrocks and Anne Donovan –I was the “lonely only” in the book, strange it would be now indeed. Was Arthur there too when a bunch of us “bought” sixpenny pillows at Auckland railway station for the long overnight trip on the Limited to Wellington, stopping of course at Mercer and remembering Shakespeare’s “mercy”/Fairburn’s “tea”, and staying overnight, first in Hamilton, in David Mitchell’s brother’s house, where I remember sleeping on a mattress in a cupboard, others all over the house. We eventually arrived in the capital, were billeted out to stay with the Wellington poets – Bill Manhire, Rhys Pasley and others – and came out billed as “The Young New Zealand Poets” in the late-late-show at Downstage Theatre. A wild party on a Wellington hill house the next night and a Sunday visit to the Begonia House capped off the weekend.

After that trip, perhaps Arthur asked – or was asked – to do the 1973 book? Arthur, quiet, kind, caring, patient and with his own agenda always; plus those witty poems he wrote and read in his droll manner, as well as his talent with music and journalism, always innovative. The hardest thing for me was to write a little preface to my group of poems in TYNZP “why I write” – but I now still believe every word of what I wrote then. I’m glad he asked.

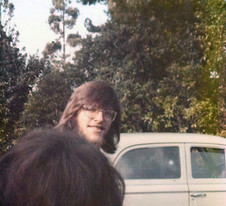

Arthur Baysting, Auckland, c. 1970. - Jan Kemp

The colour photo from the Aotearoa New Zealand Poetry Sound Archive website, I took of Arthur in Titirangi, either after a gathering at his and Gene’s house there, or someone else’s. Perhaps they’d already moved by then to Parnell, where they held the most wonderful garden party imaginable and which so many writers and artists happily attended.

Arthur also once worked with me on a script for the ABC – perhaps he was then living in Australia – as my guide and editor through writing the script of a conversation between a young New Zealand woman poet visiting the first big city of her life, Melbourne, and her reactions to it, being interviewed by an inquisitive journalist.

Arthur Baysting, a fine facilitator and gentle friend. Bravo Arthur! Toitoitoi! as we say in German, as if madly waving bunches of toetoe – and, thank you!

Terence Hogan: an accomplice to his enthusiasm

I first met Arthur sometime in 1970, when he and Jean lived in a tiny flat around the back of a house in Parnell. Being immediately attracted to these two warm and interesting people, and living close by, I began to drop in. In a sense I’ve never stopped dropping in.

Arthur was the first person I got to know well who made a living, of sorts, as a writer and who called himself a poet. As the blurb on the back of his 1972 collection Over The Horizon says, he “participated in poetry readings in theatres, dance halls, universities, coffee bars, arts centres, churches and a graveyard”. He and Jean hand-set the book in metal type themselves, with no previous experience. I was very impressed.

By the time they’d moved into the historic Kinder House at the top of Ayr Street we were firm friends and I visited regularly, relishing the talk, laughter, and endless cups of tea. Their occasional Sunday afternoon parties on the sprawling back lawn among the old oaks and totaras, attracted artists, musicians, writers, and non-conformists from all over town. These leisurely gatherings live on, and with a somewhat louche reputation, in the informal history of the Kinder House gallery.

For Arthur and I the music was a strong bond from the start, along with a cultural like-mindedness in all sorts of ways. Our musical tastes overlap considerably, but not entirely. He was writing record reviews in the early 70s, regularly getting albums in the mail, and I was glad to claim the occasional leftover. At the same time, I learned much from Arthur’s focus on the songs and the songwriters’ craft, his thoughts often illuminating details that had eluded me, in whatever we were listening to. By then he was writing songs himself, with his 70s work culminating in the hit for The Crocodiles, ‘Tears’, which he wrote with Fane Flaws. And the fine songs have just kept on coming.

Arthur is forever at work, pushing on with projects, and always keen to collaborate, exchange ideas, and draw you in as an accomplice to his enthusiasm. One 70s afternoon I found myself on camera beside the Ponsonby reservoir, hair slicked back, singing doo-wop harmony to a satirical song of Arthur’s for broadcast on TVNZ. You have to love a friend who talks you into something like that.

We checked out bands and films, shared records and magazines, and hung out wherever something might be happening. Arthur has an abundance of friends, acquaintances and associates, and knowing him has always meant getting to know a much wider world, and coming into contact with lots of other busy, creative people: timely examples for me back then, of doing what you enjoy and getting on with things. Which is what Arthur does.

As the 70s raced along, changing circumstances and the tyranny of distance thinned out our contact, but not the bond. I dropped in when I could. Arthur and Jean lived in Wellington for a period and I recall during one visit a typical afternoon brainstorming on a script of some sort (Arthur always has a script on the go), exploring some newly bought second-hand records, then heading off to see The Wide Mouthed Frogs: work/fun, music, then more music.

Eventually they moved to Sydney. Arthur’s darkly comic alter ego Neville Purvis had been indiscreet on live TV, disrupting Arthur’s freelance work in New Zealand. I moved to Melbourne myself in 1981, but they were on their way back to Auckland not long after. We’ve never lost touch, never stopped sharing the music and anything else that grabs us, and providing a bed whenever the other is in town.

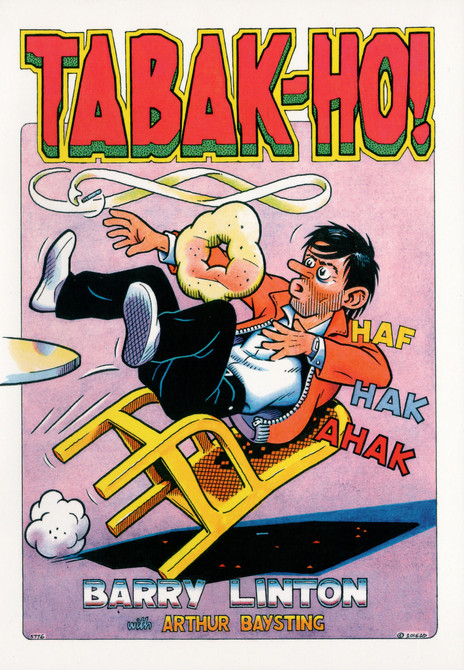

Tabak-Ho! by Barry Linton with Arthur Baysting.

In recent times Arthur has battled to have our late friend Barry Linton’s comics and graphics fittingly anthologised, and Barry and Arthur’s collaboration Tabak-Ho! (Steele-Roberts, 2017) is typical of Arthur’s work: sharp, funny, unpretentious and, as always, engaged with others in the most positive way.

Ian Wedde: subverting “official culture”

Arthur first became known to many as the performer/stand-up comedian Neville Purvis, associated in the mid-70s with the loose confederation Red Mole, whose members included poets, in particular Alan Brunton, musicians such as Jan Preston, also the crews of Red Alert/The Drongos (Tony McMaster, Jean McAllister et al), and various carnivalesque performers, notably the fearlessly extravagant Deborah Hunt. What these poets, performers and musicians had in common with Neville Purvis was the manner in which they embraced the Red Mole manifesto:

1. to keep [the] romance alive.

2. to escape programmed behaviour by remaining erratic.

3. to preserve the unclear and inexplicit idioms of everyday speech.

4. to abhor the domination of any person over any other person.

5. to expend energy.

The objective of these principles, uttered in a droll, pugnacious tone, was to subvert the decorous requirements of what might be termed “official culture”: the literature, theatre, art and music that burnished the refined tastes of the few at the expense of a broader, diverse spectrum of cultures.

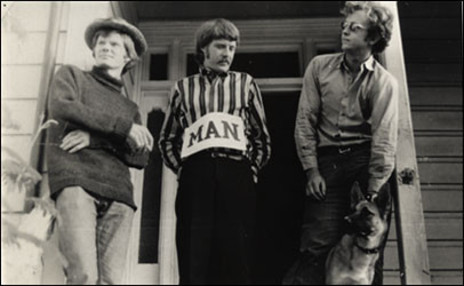

Ian Wedde (at right) with Alan Brunton (left) and Russell Haley. - courtesy Ian Wedde/nzepc

This was symptomatic of a shift that began in the 60s with what was, depending on your point of view, reviled or celebrated as “Youth Culture”. “Sixties Youth Culture” had its roots in music, protest against the war in Vietnam, and radical organisation exemplified by the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley, California. Songwriters and poets – poet-musicians, if you like, such as Joni Mitchell (‘The Dawntreader’) and Bob Dylan (‘The Times They Are a-Changin’) – were central.

Before he became the stand-up Neville Purvis, the poet Arthur Baysting participated in this refranchising of poetry as belonging as much to youth as to the literary establishment. He did this by both contributing to and editing The Young New Zealand Poets, published in 1973. His editor’s Introduction acknowledged the broadsheet magazine Freed, founded by Alan Brunton in 1970, and noted with modestly concealed satisfaction “one older poet going so far as to describe the first issue as heretical”.

At the time it was published The Young New Zealand Poets – despite what was and is seen as the under-representation of women in it – advanced into cultural debate, while at the same time being simply timely. Arthur’s subsequent career has taken many turns, including his admirable work for the Green Ribbon Campaign. Most obvious though has been his continued trajectory from The Young New Zealand Poets close on 50 years ago into songwriting and music: his poet-musician trajectory.

Arthur is not one to big-note his commitments, though the line-up of musicians and bands that have used his songs, and the projects that have benefitted from Green Ribbon and from his Apra commitment – not least the Apra Children’s Music Awards – is lengthy and distinguished. And we’ve now had two New Zealand Poet Laureates, “Fast-Talking PI” Selina Tusitala Marsh and “The Mad Kiwi Ranter” David Eggleton who, while not descended directly from those “Young New Zealand Poets”, do owe a debt to the poet-editor-musician who opened the door to the times that were a-changing back then.

Neville Purvis got his own TV show, The Neville Purvis Family Show, back in the early days, but got shut down in 1979 for using “bad language”. Ah well, Neville, no harm done, in fact a lot of good, over the years.

Ken Williams: life-enhancing endeavours

Arthur Baysting has always seemed to me to be one of the good guys. That feeling was reinforced recently when I became aware that, in collaboration with the Australian actor-singer Justine Clarke he was creating songs for children, a most worthy enterprise. Clarke was one of many Australian theatricals to have entertained and educated the very young, and their parents, on the long-running ABC-TV series Play School.

First encounter with Arthur – though personal acquaintance was to come some years later – was in 1973 when I succeeded him as writer on, ahem, serious non-classical music for the esteemed Listener. If memory serves, Arthur’s valedictory piece was the tour by the Rolling Stones; my first was on a forthcoming visit by John Mayall.

Arthur made a lasting impression (I chortle even now) later in the 70s as the wide-boy Neville Purvis, “at your service”: a purveyor of anything dodgy, transparently bent but devoid of self-awareness. Marvellous.

The brilliant Baysting and the fan Williams met at that time (a tour with Red Mole perhaps?), and again once or twice in Melbourne where I have lived these nigh 40 years. These encounters were through our mutual friend Terry Hogan, who often had reports of some new Arthur endeavour, all of which seemed intelligent and life enhancing, a far cry from the bodgie Purvis. But it brings a smile to think that Neville was never far away.

Martin Edmond: earlier incarnations

I first met Arthur in Auckland in 1972. I was dropping out of university “to become a poet”, and one of my lecturers – Denis Taylor probably – in despair at my insouciance but with a generous eye towards my future, sent me round to see him at his flat at 2 Ayr Street, upstairs in the old Kinder House in Parnell. This because Arthur was editing a collection of writing about Auckland to which Denis thought I might be able to contribute. I was a confused young man of 20; he was five years older; kindly if circumspect. I don’t think he knew why I was there either.

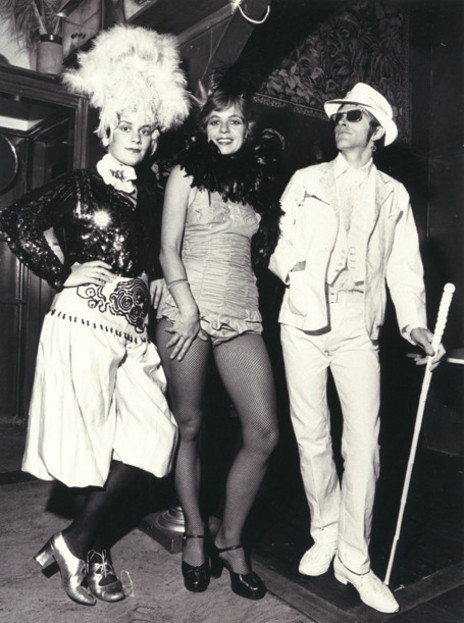

Deborah Hunt and Sally Rodwell of Red Mole, with Neville Purvis (Arthur Baysting) backstage at Cabaret Capital Strut, Carmen's Balcony, Wellington, 1977. - Red Mole archive/new zealand electronic poetry centre

The flat was full of stuffed birds on pedestals on loan from the Auckland Museum because Arthur’s wife, Jean Clarkson, was using them as models in her art-making. She was drawing bird-headed people. I never wrote anything and I don’t think the book appeared either. This was Arthur in an earlier incarnation, as poet and man of letters; his anthology The Young New Zealand Poets would be published by Heinemann in 1973; it’s a fine selection of work and still a valuable resource from those years.

The next time our paths crossed was in Wellington, when the first Red Mole cabaret, Cabaret Paris Spleen, opened at the Performer’s Theatre in Courtenay Place in 1975. Arthur wasn’t in that show, but Jean made the poster for it and also did artwork for Spleen: a useful organ, which started the same year. Arthur was a regular contributor to the magazine too, writing long, multi- or mixed-media articles about Split Enz and the Red Hot Peppers; a sci-fi country and western fantasy; and an educative piece about the perils of embracing nuclear energy.

He made his own debut as a performer with Red Mole in 1976, at the second cabaret, Cabaret Pekin 1949, at Unity Theatre at the bottom of Courtenay Place. When I asked him what he remembered about the show he said, “Jean made a huge winking cardboard sun to a Brian Eno soundtrack.” The song was ‘Taking Tiger Mountain’ from Eno’s 1974 solo LP Taking Tiger Mountain (by Strategy).

I also asked him where, when and how Neville Purvis originated. He said, “The character, but not the name, came during Holyoake’s Children when Jean dressed me as a bodgie and I spontaneously broke into song.” Holyoake’s Children – the allusion is to Robert Patrick’s 1973 play Kennedy’s Children – was sketched by Alan Brunton for Cabaret Pekin 1949 and revived during the delirious seven-month long season of Red Mole’s Cabaret Capital Strut at Carmen’s Balcony. Item 3 on the one-page scenario for the first of those cabarets, in March 1977, reads: Arthur Baysting, Emcee + continuity.

This was the first public appearance of Arthur’s much-loved, much-abused alter ego Neville Purvis. Neville Purvis, at your service, he would say. That’s Neville on the level to you. Neville was a spiv. He wore white shoes, white trousers, white shirt, white waistcoat, white embroidered jacket, white hat, a black greasepaint pencil-line moustache, dark sunglasses, and carried a white cane. He was from Lower Hutt and he lived with his Mum. He drove a Mark II Ford Zephyr and his milieu was one of petty crims who hung around billiard saloons and boarding houses, pubs and burger bars. He was smart but he wasn’t: I thought fast and, when that didn’t work, I thought slow, which is me normal pace.

Arthur spoke Neville in his own voice: flat, nasal, a bit monotonous. His mode was a mix of the laconic, the satiric and the naïve. In his fiction, he wasn’t part of Red Mole: after he’d got out of Mt Crawford Finishing School – jail – Red Mole asked him to come and lend them a hand. He positioned himself as an outsider and so might refer to the acts he introduced as something beyond his ken. He liked to bait the audience and the audience liked to heckle him back. He had a few standard rejoinders: You just keeping taking the tablets, darlin’, was one. A saga on the lager was another.

He told shaggy dog stories and jokes that were funny in a bathetic, low-key kind of way. Once he imagined being asked what the Hutt Valley was like before the Pākehā came. Miles and miles of empty state houses, he dead-panned. Neville was not, not ever, politically correct. In another routine he evoked the famous New Zealand painter Genghis McCahon. Murray Edmond recalls a third, the tale of the fate of the winner of the annual Silver Plough contest:

As the winner drove home, up the Foxton Straight, in his Zephyr, “his mind must still have been on ploughing that straight furrow” – and here Neville inserted the only movement in his stand-up comic talk – his right hand went forward to grasp the imagined steering wheel while he turned his left arm, shoulder and his head to look behind him at the disappearing road, in his mind, the straight furrow. The head-on collision did not have to be mimed or named to be imagined by the audience: “He had ploughed his last furrow.”

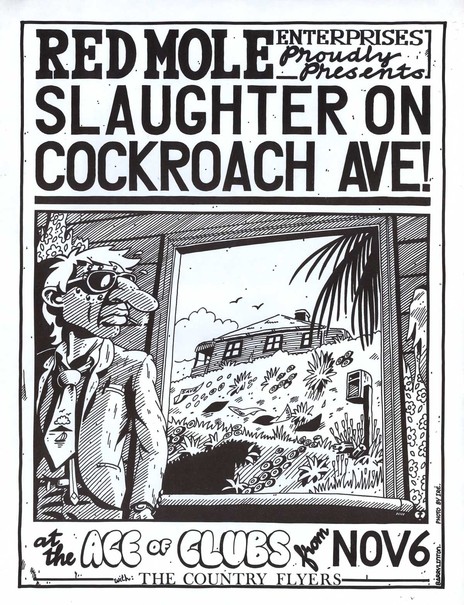

Neville was intrinsic to the cabaret; he strung things together, night after night; his thin white thread ran through the outlandish exotica of the rest of the acts. He was also beginning to write lyrics for songs. There was one he sang himself, with backing from The Country Flyers, during Red Mole’s Slaughter on Cockroach Avenue at Phil Warren’s Ace of Clubs above the old Cook Street markets in Auckland. ‘Money’, it was called and included the line “pictures of the Queen” to refer to banknotes.

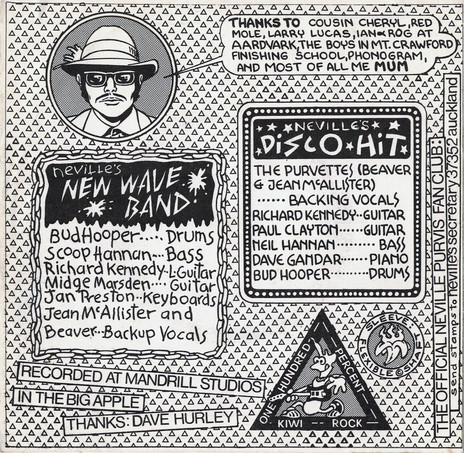

Red Mole's Slaughter on Cockroach Ave was performed at the Ace of Clubs Auckland, November 1977. Alan Brunton wrote the "scenario"; the music was by Midge Marsden, the Country Flyers, and Jan Preston - Barry Linton

For that show Arthur also wrote the lyrics for a beautiful reggae tune, music by Neil Hannan, bass player in The Flyers, which Midge Marsden sang, with backing vocals by Beaver and Jean McAllister, sometimes called The Purvettes: “O Rangitoto/ Sitting in the harbour/ Rangitoto/ Sitting in the bay.” Midge performed that song for the next 40 years. Both these tunes were recorded; ‘It Takes Money’ b/w ‘Disco on my Radio’ was released as a single.

I missed Neville’s solo career because I was away overseas with Red Mole. I next encountered Arthur in Sydney, where he had come after being banned from the airwaves for being the first person to say “fuck” on New Zealand television. At least we never said “Fuck” was the last line of the last Neville Purvis Family Show. I remember asking him if he thought of himself as an exile: Nah, he said, that’s too romantic for me. Down to earth, as always.

In Sydney Arthur organised and introduced the annual Kiwi Nights, which took place at the Astra Hotel in Bondi and were riotous evenings of music, comedy, drag and who knows what else. I don’t know how they got the gig but it was a good one.

Not so long ago I ran into Arthur at Café One2One on Ponsonby Road; it was during a Sunday afternoon gig by Sam Ford and Trudi Green. I was visiting to look into the Brunton/Rodwell archive in Special Collections at Auckland University. Arthur was with Bill Lake, one of his songwriting partners; Bill, with his band The Right Mistake, had a gig on the North Shore later that evening, promoting their CD As Is Where Is. Arthur contributed to about half the tracks on that excellent album. As usual, he was business-like. Have you got anything in your book about Red Mole’s work with kids? he said. If you haven’t, you should.

Arthur Baysting reunites with Carmen, Sydney, 2009. - Jean Clarkson

Jean McAllister: making things happen

The first time I had a conversation with Arthur was in Wellington in the gallery space next to Carmen’s Balcony strip club. Jean had an exhibition of her bird-headed figures and was minding the store. Arthur was waiting for the rest of Red Mole to arrive for rehearsal, smoking a roll-your-own, absorbed, taking notes.

I remember how kind and engaged as artists and performers both of them were. They were an attractive couple; Jean artistic, stylish, cheerful and Arthur, laconic, rail thin, clearly intent on developing his alter ego MC, Neville On the level Purvis at your service. I was a green young singer, a student, not quite sure of my part in the heady, intense Cabaret Capital Strut. I had no idea why Jean and Arthur would take any interest in me, but as we talked I knew I had found life-long friends.

The cabaret was wildly popular in Wellington. While Red Mole’s roots were theatrical, political and literary, Neville was pointedly none of those. He turned out to be a genius creation, a character about as different from Arthur the man as it was possible to be. Neville was just out of “Crawford finishing school”, a small-time crim from Naenae. He was “helping out his mates” as the MC for the show. Dressed in a rumpled skinny-legged white suit, carrying a white cane, wearing a white fedora, shades and a pencil moustache he was the sleazy showbiz bodgie. The audience loved him, Neville took their heckles and responded in a flat monotone. Neville wasn’t the sharpest tool in the shed. He got his best ideas from having “a saga on the lager”.

The Country Flyers were the Cabaret’s house band, music was an intrinsic part of the show. Arthur was always a big fan, a passionate listener and connoisseur of great songs, with a keen memory for quoting his favourite lyrics. Carmen lost her lease on the Balcony and the Moles and band moved to Auckland at the tail end of 1977 for cabaret seasons at the Ace of Clubs for Slaughter on Cockroach and Pacific Nights at the Sweet Factory in Parnell. But the audience in Auckland was smaller, lacked the Wellington vibrancy, we were all looking for the next move.

Arthur had started contributing lyrics to songs for these shows. He wrote ‘Hey Rangitoto’, Neville wrote and performed ‘It Takes Money’. We all got together to record half an album’s worth of songs in a crowded marathon session one long night in the summer heat at Mandrill studio. Beaver and I sang backing vocals and were credited as “The Purvettes” on ‘It Takes Money’ which was released as Neville’s single.

Joe Wylie's illustration for the back of the picture sleeve for Neville Purvis's single 'It Takes Money'/'Disco on My Radio' (Vertigo, 1977). - Joe Wylie

Around this time my brother Neil died tragically. My father, brother and I were reeling with grief and I went home for a few weeks to be with them. Arthur sent a heartfelt but typically straightforward letter saying, “There’s nothing I can say about your brother except sorry, and you should come back to Auckland to work on the new show.”

That was Ghost Rite. Neville’s routine was part of the first half of the show but by now he wasn’t linking the acts, he was his own. Arthur and Jean helped me paint the mask I was making for the show. It was a duck’s head, right up Jean’s alley! I was still in mourning and the intense work was a good distraction, but Arthur and Jean seemed to know that it wasn’t quite enough. I felt buoyed up by their help in painting that mask, I’ll never forget their care and attention at that time.

Right before I left for the US in 1978 I went to say goodbye to Arthur and Jean. I was excited and terrified about leaving, it was a plunge into the unknown. They told stories about their own trip through the US and assured me that it was the right thing for me to do, to embrace the adventure. Then they gave me a parting gift, a book of cartoons which I took with me and have to this day: B Kliban’s Never Eat Anything Bigger Than Your Head and Other Drawings. On our travels, it was brought out often, we would go through it and howl with laughter.

I was away in New York with Red Mole and our band the Drongos for the best part of the next decade so only heard about Neville’s TV show, his notorious sign-off line, Arthur and Jean’s move to Sydney. We stayed in touch, one of Jean’s prints went up on my wall and I thought Fane Flaws’ and Arthur’s ‘Tears’ was amazing.

The Drongos came back to New Zealand for a tour in 1985-86. The night before we were due to fly back to the U.S. Arthur and Jean came to our hosts’ place in Grey Lynn for a farewell dinner. I was five months’ pregnant with my first child and Jean was almost due to give birth to her second. Over the course of the evening she was quite uncomfortable and needed to move around. We said goodnight and Jean and Arthur set off on their short walk home. The next morning, Arthur called to say that Jean had gone into labour on that walk and given birth at home a couple of hours later! We stopped by on our way to the airport to welcome and kiss goodbye, for a while at least, baby Rosie.

Back in Auckland at the end of the ’80s, Arthur suggested we get together to write some songs. I had contributed to The Drongos originals but wasn’t the main songwriter, felt out of practice and unconfident. Arthur was prolific, he was writing constantly. He quickly came up with some lyrics, put them in front of me and said, “Sing this”. It was a country break-up ballad called ‘Goodbye’. I strummed a waltz, jokingly improvising the first tune that came to mind to fit the words into. Arthur was happy but had a few interesting directions: “Go up on that line!” “Repeat that bit!’. For someone who has never claimed to be a singer, Arthur still knew where the song should go. After only a few minutes the song was done and recorded on a cassette. Later, Arthur shopped it to Slim Dusty’s daughter Anne Kirkpatrick and she included it on her CD Out of the Blue, which became the Australian country album of 1992.

Arthur has always been good at making things happen. More than just for himself though, he‘s acted as a true believer in New Zealand creativity and built a community of collaborators. His old friends are not forgotten. Not too long ago, he spotted his mate, the brilliant comic artist Barry Linton getting off the bus. Barry had emphysema and struggled to cross Ponsonby Rd. Arthur, shocked at his condition, was prompted to make a deal with Barry: “Stop smoking for a month and I’ll come and work with you every day to make a new comic.” He did just that. Barry died not long afterwards, but Arthur helped him to spend that time together doing something they both loved.

At a music night at Arthur and Jean’s a few weeks ago, Tony [McMaster] and I sang Hey Rangitoto’, learned from the 1978 recording. Arthur listened as afterwards a friend was prompted to announce to everyone that the song is still a Ngāti Whātua taonga 40 years on.

Hey Rangitoto

Sitting in the harbour

Rangitoto

Sitting in the bay

Yeah the people they come and go

Rangitoto here to stay

Ian Mune: Renaissance man

I knew Arthur’s poetry before I knew Arthur.

The Last Moa

the warriors were young

and careless, had snared

several pigeons already so

the ambush was ill-prepared.

when they showed themselves

too soon, the bird hesitated

but he knew and turned

toward them, and waited.

So when I met him I was somewhat in awe, and a little startled at how we connected.

When we were schoolboys, poets were people with other jobs. Something happened in the 60s and 70s. An academic, a poet, an actor and a businessman set up a theatre – Downstage – which wasn’t supposed to be possible. People like Arthur didn’t think it was strange to be a poet without another job. There were others – David Mitchell, Paul Grey.

I was trying to get a script together for Roger Donaldson’s upcoming Sleeping Dogs. I asked Arthur if he’d like to get involved. He seemed to think that was a reasonable suggestion, so we co-wrote that and, not to look a gift-horse in the mouth, I got him onboard with a TV series I was working on: The Mad Dog Gang Meets Rotten Fred and Ratsguts. It was Arthur who came up with two new and important characters: a ewe named Mrs Woolworth and her lamb, Gladwrap. The name comes from the city kids seeing the birth and their awe at the shiny coat the lamb arrives in. They brought a new dimension to our story.

Neville Purvis and Cousin Cheryl - Arthur Baysting and Jean Clarkson - walk the police gauntlet to attend the premiere of 'Sleeping Dogs' at the Auckland Civic, 6 October 1977.

By late 77, when we had the premiere for Sleeping Dogs, Arthur turns up as Neville Purvis, white suit, shoes, hat, moustache and all. Where did that come from? I thought this guy was supposed to be a poet. But no, he’d already been touring with Red Mole, hooked up with Blerta, and eventually landed his own TV series, which he managed to torpedo by becoming the first person to say “fuck” on NZ television.

Rennaisance man. Although I’ve never seen him with brush in hand. I guess he chose early on to leave that to Gene with her clear, incisive prints.

In the age of Greta, this still catches me in the gut …

And That Piano

Yes, well I agree

there’s been too much

exploitation of resources

but

I like music

and that piano

was once

trees and rocks

and elephants.

Thanks Arthur.

--

Read Part 2: 1978-2019 – Rough Justice, Windy City Strugglers, The Crocodiles, Apra, NZ Music Commission, children’s songwriting, Pasifika.

Contributors

Peter Needham is a travel writer and editor, based in Sydney

Susy Pointon is a film scholar and writer, based in Northland

Jan Kemp is a poet, based in Germany

Terence Hogan is a graphic artist and writer, based in Melbourne

Ian Wedde is a Wellington poet, writer, critic and curator

Ken Williams is a former Radio i journalist and Rip It Up writer, based in Melbourne

Martin Edmond is an author, poet and screenwriter, based in Sydney

Jean McAllister, formerly of the Red Mole band and The Drongos, is an Auckland-based musician

Ian Mune is an Auckland actor, writer, screenwriter and director