The old AC/DC adage about it being “a long way to the top (if you wanna rock’n’roll)” could have been written for Nigel “Booga” Beazley, frontman of legendary stench rockers Head Like A Hole. Despite the band not being able to perform live, the singer remains wedded to the dream that began when he dropped out of the school choir circa 1980. He initially relied upon a series of well-timed mix tapes as signposts to the place he would manifest his personal superpower – that of frontman – onstage, typically presiding over a gnashing moshpit.

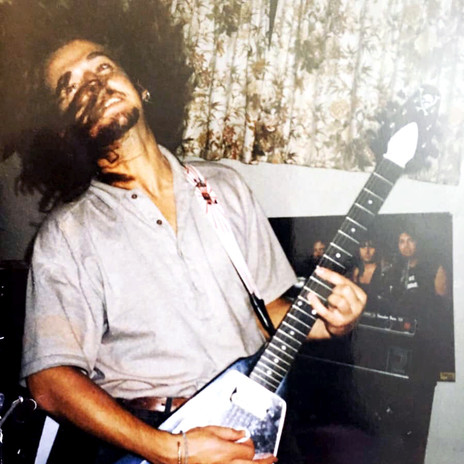

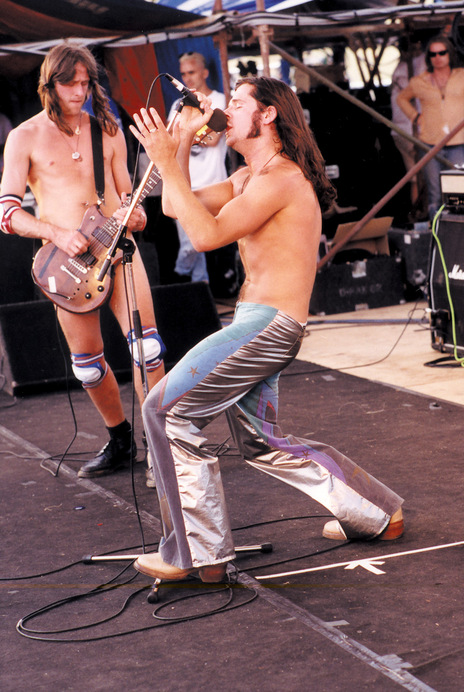

Booga Beazley and Michael Franklin-Browne on stage. - Nigel Beazley collection

“I tried to sing in the choir at primary school,” he recalls. “That didn’t go down so well. I used to get shit by some people at school because my mother could sing operatically, and she would teach the choir how to sing at the Laings Road Methodist Church in Lower Hutt.

He remembers performing in “stupid little skits” at Lake Taupō for family holidays, but – as far as music went – it took a next-door neighbour to hit his play button. “He gave me a tape – on one side was the Buzzcocks’ Singles Going Steady, and on the other side was Bronski Beat – weird combo. I listened to that one tape constantly.”

At nine years old, that tape got him to thinking, “Being in a band would be sick.”

When he reached intermediate age, an older cousin made the next influential introductions. “He was right into Kiss. He had just got back from America, where he saw Twisted Sister live, [in] 82 or 83. He said, ‘You should listen to this.’ And as soon as I listened to that, I just went on a massive metal, Twisted Sister, Scorpions, W.A.S.P., Mötley Crüe [bender]. Everything just opened up for me. I was just like, ‘Wow! That’s what I really want to do.’ I liked what they wore, the big hair, the makeup and stuff. It was just brilliant.

“As soon as I got to boarding school [Rathkeale College], same thing there. This guy gave me a tape. One side was Mötley Crüe’s, Shout at the Devil; the other was Queensrÿche. I never liked Queensrÿche, but when I heard Shout at the Devil – and I looked at what Mötley Crüe were wearing – I was just, like, ‘This is crazy, man.’ Like, just the leathers and the studs, and the flames behind them, and all the makeup. I used to look at it and think, ‘Who are these people? What do these people do when they’re not dressed up? Do they dress like this all the time?’ It was so rad. I could smell the leather and studs.”

Booga aged about 18. - Nigel Regan

By the time Head Like A Hole came along, he had added a bunch of premium era Sub Pop bands into the mix. Sartorially, his tastes were harder to label.

“I did the most stupid things. I would wear one-piece 1930s bathing suits. For some bizarre reason, I made up [the outfit of] one of those people that sell peanuts in a tray ...

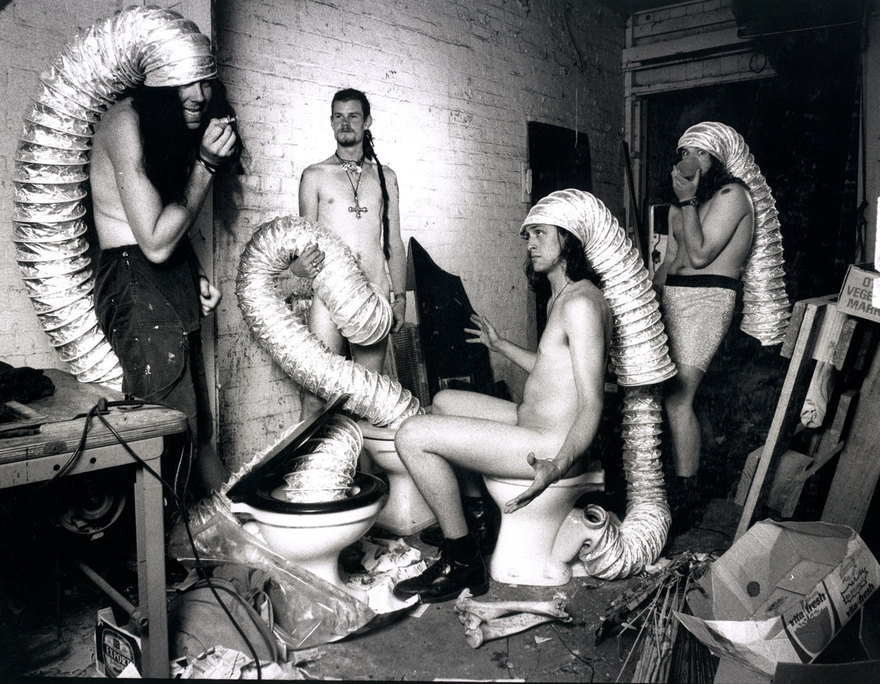

Head Like A Hole, 1992 (from left): Tallbeast, Hidee Beast, Datehole, Booga - Mark Graham

“When we went to play, Mark [Hideebeast] Hamill, our drummer, walked out wearing his studded codpiece, and a spotlight was meant to go on him. He walked out, and the spotlight wasn’t on him. He just stood there. Everyone’s shrouded in a little bit of darkness. Then, all of a sudden, he raises his arms, and he goes, ‘Well? Come on!,’ to the spotlight person. And the spotlight person finally put the spotlight on him. It actually made it hilarious.”

Guitarist Nigel “Datehole” Regan would wear Gladwrap with nothing but bits of fruit underneath the Gladwrap, and that would be on a well-dressed day.

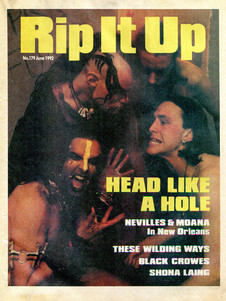

Head Like A Hole on the cover of Rip It Up No.179, June 1992.

“We just wanted to be different,” says Beazley. That difference saw them both lauded for and dogged by expectations of nudity, comedy, and unhinged behaviour.

One person who did not think Head Like A Hole were a joke was their manager, Gerald Dwyer. When I interviewed him for Capital Times, in 1992, he said, “The audience reaction has been amazing to watch … The band formed to have a good time, and they have passed that on to the punters. They have an excellent attitude towards their music … Their potential is huge.”

From their earliest days, that potential was often dogged by darkness. In 1992, their lighting tech Paul Anderson was murdered by Graeme Burton, at the Carpark venue, “on our watch,” Booga is at pains to recall.

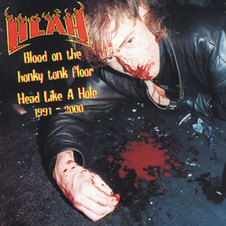

Then there was the tragic story of Blood on the Honky Tonk Floor album cover star Matt Hall. It turned out that sustaining moshing injuries at a Head Like A Hole gig would be far from the most dangerous thing to happen to him. He was in a band called Backyard Burial, and died in January 2001 as a result of a stabbing attack at his Johnsonville flat.

The Mark Roach designed cover for Head Like A Hole's Blood On The Honky Tonk Floor, 2000

Beazley worked for Dwyer’s Sticky Fingers bill posting and flyer distribution company. He recalls late nights on the town postering with Dwyer, who carried his Head Like A Hole, Shihad, Sticky Fingers, and personal finances divided between his four pants pockets.

“I’d go, ‘Do you ever get them mixed up?,’” Beazley says. “And he’d be, like, ‘No.’ But me and him would get ripped and go out on the town, vomiting out the window of his van, posters everywhere, like a couple of extreme junked-out nutters.”

Gerald Dwyer was 11 years older than Beazley, who was still a teenager when they met.

“Gerald and Lane Husband, I used to think they were the shit. Gerald was this rad dude. He was a singer of Flesh D-Vice. He became this amazing ambassador of music, and loved everything about New Zealand music and wanted to manage bands. He did everything he could in his power to get Shihad and Head Like A Hole onto the big stage. And Lane was always there, driving and shooting endless amounts of footage. These dudes that were a little bit older than us and were so good to hang out with.

“I don’t know how long it was, but they sort of hid it from me that they were doing intravenous drugs for a while, until one day, I was just like, ‘What’s so important that I can not be privy to what you’re doing in the kitchen?’ ... And then next thing you know, I started having a little bit of dabble here and there.”

Head Like A Hole onstage in 1995, with manager Gerald Dwyer in the background, in a white t-shirt. - Photo by Mark Roach

Dwyer never got to realise his dream for Head Like A Hole, dying of a drug overdose on the night of the 1996 Big Day Out. Just hours earlier an “extremely buff” Head Like A Hole had inspired Rip It Up’s Jonathan King to rave: ‘The future is in the hands of these guys, so you better watch out.’

“That whole year, he’d been, like, ‘I’m not doing any drugs. I’m staying away from it,’” Beazley recalls. “Then that happened. It was very unfortunate.”

He talks about Gerald haggling to get his bands paid, on the day of his death. “At his tangi, his face was all bruised. I found out the reason why, because he had been in a fight … then he dies …

“It was, like, what do we do now?,” Beazley recalls. “You’d think that a situation like that would make you run in the opposite direction. But, for me and Nigel, it was the completely opposite. For some stupid reason, we decided to go even further into the intravenous drug realm. And the next few years … 97 to 2000 was just a nightmare of touring. And, I mean, playing the shows was great – I played great shows, really out of it – but just the maintenance and different managers, different people in the band managing us … It was just chaos really.”

For a time, any money earned by the band seemed to be flying almost everywhere except equally divided between them. While drug use by half the band accounts for much of the fund drainage, Beazley also felt many people – who he should have been able to rely upon – let the band down.

Clockwise from left: Datehole, Booga, Hidee Beast, and front centre is Shihad's Jon Toogood standing in for an absent Tallbeast.

He was disappointed Head Like A Hole were not called upon to play with Shihad on their old friends, labelmates, and sometimes even bandmates’ recent farewell tour. It’s impossible to argue when Beazley says – for the fans – a Shihad/Head Like A Hole double bill would have been “the ultimate look back in time”.

“Who did they play most with?” he asks. “Head Like A Hole! But nah, not even.”

He recalls a moment when their shared label, Noise International, visited both bands backstage at a European gig.

“The record company were like, ‘Holy shit. You guys are blowing Shihad away. We’ve actually got it wrong. You guys should be headlining and Shihad should be supporting.’ And we said, ‘Nah, we don’t wanna do that. We love playing first.’ When they said that to us, Shihad were, like, ‘What the fuck?’ And I could see it in Jonny [Toogood’s] face, that changed the way he played on stage. I mean, he was always rad, Shihad were always rad, and tight as shit. I did the lights for them. I used to love doing the light show for them every night, because I just love listening to their really rad, you know, heavy songs.”

He says there’s no way he would ever want to go back to the old needle-and-spoon lifestyle that turned his life upside down.

“I wish I never had, you know, because I’m probably, probably having health issues because of it ... maybe. The stroke wasn’t anything to do with drugs, apparently.”

That would be the minor stroke he suffered late last year. Speaking on the phone, across a couple of sessions in the darkest part of winter, he reaches for words that occasionally seem elusive – someone’s name, names for things.

“It’s been ratshit, actually,” he says. “It’s taken six months to get feeling relatively normal. It seems like a small thing to happen – blood clot into the brain – and then you’d think you’d make a recovery, if you’re not dead. I just didn’t think it was going to be as hard as it is. You just feel like shit the whole time. I’ve been going through dizzy spells, which sucks. How the hell am I gonna sing, you know, like all that air out of my lungs? I’m gonna have to address that at some point with a rehearsal. I’m just going to get my shit together and feel better.”

Head Like A Hole, from left to right: Andrew Ashton, Booga Beazley, Simon Nichols, Nigel Regan, Michael Franklin-Browne. - Bradley Garner

He also suffers from severe tinnitus he is keen to get a handle on. His own health was not the only reason Head Like A Hole were forced to cancel gigs in December 2024 and February 2025. Bassist Simon Nicholls has also been laid low.

Beazley explains: “He’s got cancer, which is terrible. He’s going through a very hard time.” (Beazley organised a Give-a-Little campaign for Nicholls, raising over $10,000.)

“So, we just had to put things on hold while Simon was having chemo. I just wasn’t sure when we could get back on stage.”

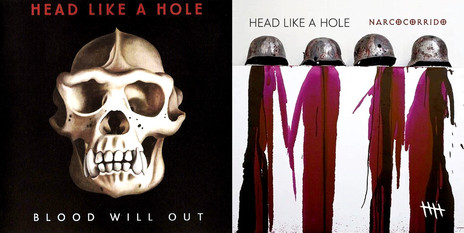

Head Like a Hole - Blood Will Out (2011) and Narcocorrido (2015)

After all, there is still so much to prove. Two uncompromisingly heavy studio albums – Blood Will Out (2011) and Narcocorrido (2015) – have failed to blow the cobwebs of Head Like A Hole’s wild youth away from established points of view.

“People that seem to think they know what bands are really great, successful and deserving, see us us as sort of this weird, ‘Yeah, they’re cool, but they’re not really worth much,’” says Beazley. “When we get offered shows, I sometimes feel like, ‘Are you kidding me?,’ when I look at the fee, ‘I think we’re worth a lot more than this.’ It feels like, ‘We’ll just get Head Like A Hole, mate, because they’ll play for fuck all.’ I get what it is, you know, you’ve got to be playing constantly and releasing music constantly, be relevant and build up your profile, and that equates to how much money you get paid for certain things. But sometimes I just feel it’s like we’re a bit of a joke sometimes. It’s a weird feeling.”

Booga Beazley in Porirua, 2021. - Nigel Beazley collection

He considers the New Zealand Music Awards, where the band were filmed ostentatiously not winning in 2012, for the 2017 Swagger of Thieves documentary.

“We’ve tried to win an award there, we failed, and we’ve never really been back. And it’s turned into a big corporate, thing now. Every time I watch some of it – I don’t usually – I look at the people that are nominated into the Hall of Fame, and I think to myself, I think New Zealand’s running out of bands to put in the Hall of Fame ... I wonder if they’d ever decide, ‘Maybe we should nominate Head Like A Hole?’ But I know that they could never do that, because – in their eyes – there’s nothing good to say about us. Usually it’s, like, ‘Oh, they’ve won Silver Scrolls …’ There is a dot next to our name. Just imagine. It’d be hilarious. ‘They’ve done nothing. They used to play naked.’”

For now, when Beazley talks about heading to “the studio”, it’s his tattoo shop – Zardoz Tattoo Studio, in Paraparaumu – he means. While some people come looking for Head Like A Hole tattoos, or to know they’ve been tattooed by the band’s singer, Beazley’s real passion is traditional tattoos.

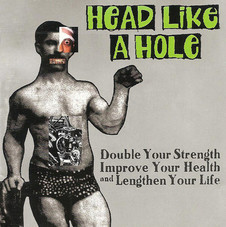

HLAH – Double Your Strength, Improve Your Health and Lengthen Your Life (Wildside Records, 1995)

Fans can look forward to a new vinyl release of 1995’s Double Your Strength, Improve Your Health and Lengthen Your Life. As for new music, steady inspiration can be hard to come by when those things that once worked for a process are removed or no longer work.

“When we were together, as a young band – very young – I’m living the certain lifestyle which equated to writing some of that music we did. Thirty years on – your body and your brain – you’re not living that lifestyle. It’s hard for me to write lyrics now, because it’s just totally different. I’m not being an idiot like I was back then. So, what do you, what do you write about? Being in a family?”

Would he ever write about that?

“No,” he says plainly. And being a parent impacts on his sense of expression in other ways too. His 19 year-old daughter lives downstairs from her parents, and is not backward about telling them to turn down the “thumping” if the stereo gets too loud upstairs.

“I usually bash the music out at the [tattoo] studio, you know, so I don’t have anyone telling me to turn it down or not play certain things,” he says. “I won’t listen to modern music, unless it’s something no one would think that I’d be listening to. I had a fascination with Dua Lipa for a while. I’ve been listening to Lola Young. She sounds like Shona Laing. I think she’s pretty awesome. I don’t really listen to pop music, but when I do hear pop music that I think’s rad, like that, I don’t mind. Apart from that, I’ll be listening to metal all the time. I might listen to some 70s classics. I’ll just listen to anything that’s really good. Even The Beatles, mate. I’d probably never, ever put it on, but if it came on the radio, I’d keep listening to it. But it’s The Rolling Stones over The Beatles any day for me.”

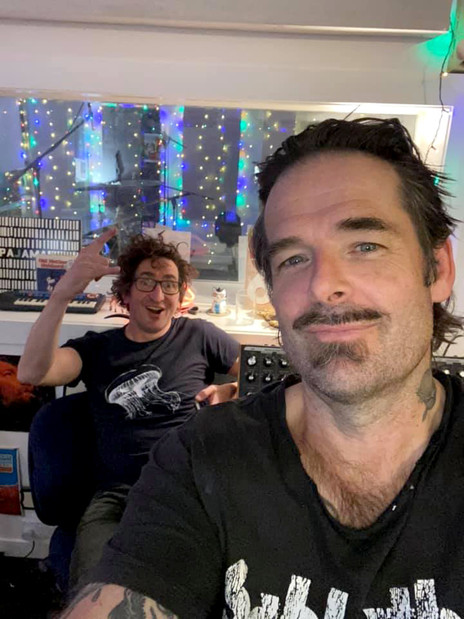

HLAH's Booga Beazley and Michael Franklin Browne at Depot Artspace in Auckland, 2021. - Nigel Beazley collection

He believes what prevents Head Like A Hole from being wildly successful could be around the quality of their songwriting. Despite having lyrics stashed “all over the place”, he’ll sometimes wing it when it comes to laying down a vocal track. He’s also taken lyrics from other people.

“A couple of years ago, my nephew was messing around with music, and he sent me a few ideas. I actually borrowed some lyrics and a bit of music. He was, like, ‘Do with it what you want.’”

Head Like A Hole - One Foot in the Grave single (2024)

That not only scored young Caleb Beazley a songwriting credit for the 2024 HLAH single ‘One Foot in the Grave’, he also co-starred in the single’s video, with his brother Raphael Beazley, who shot the clip (without the band) in Byron Bay and Melbourne, Australia.

‘Demons’ (2021) was another track which benefitted from an offering of lyrics, by HLAH superfan Bridget Powers.

Beazley says he honestly doesn’t know what he wants to sing about these days. Sometimes television helps with that. Single ‘The End of Life’ (2017) added some Star Trek inspiration to a riff of Regan’s. ‘Monstax’ (from Blood Will Out) was all about Chalky White from Boardwalk Empire.

He’d like to get back to performing, but geographical logistics join health issues with Beazley living in Raumati, drummer Michael Franklin-Browne in Whanganui, and the rest of the band living in Tāmaki Makaurau.

“I’d like to do music with someone else,” Beazley says. “When you play guitar, you can just basically bowl around someone’s place, pick up a guitar and start playing away, yeah? And, if you can sing, hey, cool. That’s a bonus sort of thing. But, for me, it’s not like that. It’s like, well, I don’t really play guitar, I’m just just a singer. So, that’s quite hard doing it that way. I’m always open.”

--