Jazz drummer, groundbreaking manager of Th’ Dudes, pioneering café venue proprietor and restaurateur, innovative cinema operator, Charley Gray has lived on drive, passion and ideas. This interview was first published in ChaCha, November 1984. Gray’s next move was to establish Charley Gray’s art-house cinema in the old Capitol theatre on Dominion Road. It was described as a “24-hour film festival” and was again ahead of its time. In 2012 Charley Gray returned to music as a DJ, playing jazz and world beat at Auckland’s Golden Dawn, double-billed with Murray Cammick.

--

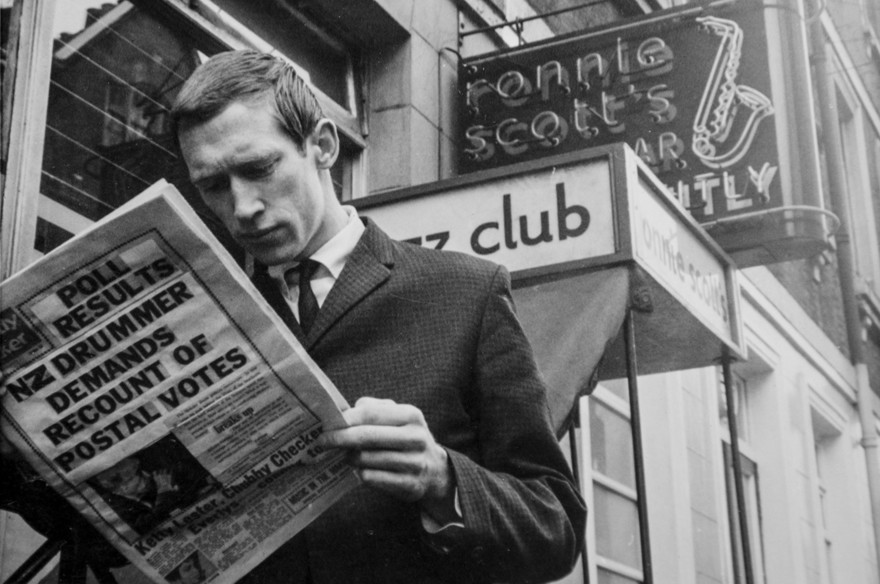

Charley Gray outside Ronnie Scott's jazz club, London, c. 1963. - Bryan Staff collection

Some people believe in an overwhelming sense of destiny, which spurs them through life, justifying their actions, and convincing them that whatever they do is inevitably right. People who make their living by being themselves – by making their own tastes and visions available to others, and as a result either become wealthy or bankrupt.

Currently on the “ladders” rather than the “snakes” side of fortune is The Famous Last and First Café partner Charley Gray, who reveals that life hasn’t all been roses on the back fence …

When did you come to Auckland?

When I was 15. I went to schools in the Bay of Islands: Edgecumbe, Whakatane and Morrinsville. The public career as such is probably a reaction to my under-education. Music was my out.

I wanted to be a drummer. I studied technique under Mauri Faiers [NZ Jazz Trio]. But of course the real teachers were Philly Jo Jones and Elvin Jones. You know, the ego is a very healthy thing. The reason I was so into music was this feeling, even as a little boy, of not wanting to be one of the soldiers, but to be something a little more. But this is also why I was a bad drummer. I mean I could attract attention – which would have been great if I was a sax player or something like that, but I chose to be a drummer. So I was using drums as a crutch to attract attention to me, rather than keeping good time. And of course there would be these pissed-off soloists looking around wondering what on earth I was up to.

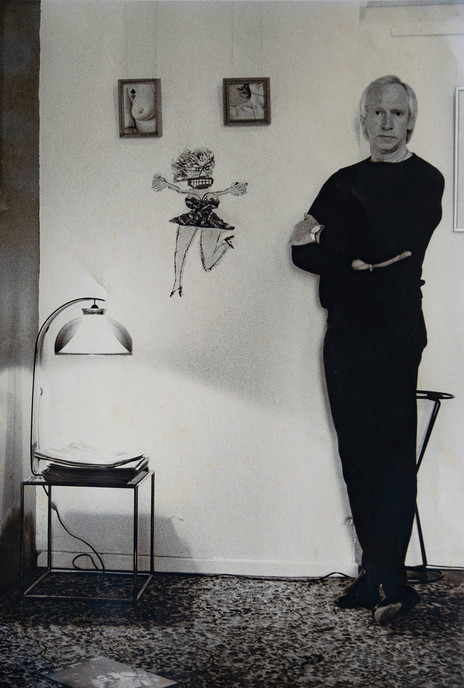

Charley Gray, 1984. - Bryan Staff

Did you ever plan to make a living playing the drums?

I remember going on tour with Howard Morrison as my first paying job at the end of the fifties. We were a six-piece band – I wasn’t really good enough to do the job, but I got paid $30 per week. It was a long, three-month tour of little places like Murupara. Then, right at the end in Morrinsville I came down with appendicitis and had to be rushed to Tauranga hospital. Benny Levin put the tour on, and ended up working in a lunch bar up in Ponsonby afterwards, I think because it cost him so much money. But it pointed the way for me, at that stage I really wanted to make it as a drummer.

As a drummer in New Zealand?

There wasn’t much happening in New Zealand, especially in jazz, so I gradually announced to everyone that I was off to Britain; and that became a thing in itself for six months or so – “oh Charley is off to Britain” … so that when I actually stood on the deck of that ship, I got cold feet, turned pale and thought, what have I gone and done? I mean it is a whole lot different now, my youngest boy Warner has just gone to Switzerland. And a day or two later he rings me up – collect, of course – to announce that he had arrived. No, going to Europe in those days by boat was a whole different thing.

And did you do the whole musical pilgrimage, hang out with musicians and such?

Mmm, yes. 1962. The Establishment [Peter Cook’s satire and jazz nightclub] was where I would go the most. Or the Marquee or Ronnie Scott’s. I arrived in London with £100 and immediately bought this and that LP that I had always wanted. Soon I was down to £6. I took a job in Notting Hill for £8 per week, and a room at £5. I just disappeared into that room and lived the most miserable existence for a year. That winter of 1962 was the coldest in Britain for over 100 years. I went down to about seven stone.

Murray Cammick and Charley Gray DJing at Golden Dawn, 2012. - Simon Grigg

What broke the pattern of that lifestyle?

Meeting Ann, who was to become my wife. She was a receptionist at the firm where I worked. Up until recently, my success with women always came from the women. I never got anywhere unless the woman decided that I would. So Ann had seen me and picked me up. We came back to New Zealand together when she became pregnant. It cost her £10 to come out, and my parents put a deposit on a time-payment fare. We came back and got married about a week before Miles was born.

Is he named after Miles Davis?

Of course.

So who is your second son, Warner, named after – Tim Murdoch?

Ha ha, can we say that I said that? No, both boys were accidents. Poor people don’t plan families. We came back to a state flat in Onehunga. I used to hang around in those days with a film-maker called Don Cauldrey. He had the reputation for turning on the Beatles when they came out here.

When did you first come across pot yourself?

In London. I wouldn’t have anything to do with it before that, because I didn’t want to get hooked! But these musicians I idolised would go for a walk around Soho Square during their breaks at the clubs, to smoke a joint. So I tried it and it didn’t do anything for me; and then came my annual holidays from the warehouse and a drummer I was friendly with said, “Buy yourself some grass, go home and get yourself stoned”. This is 1962. So I took this little pipe, and I put on a record – I’ve still got it, Tune Up by Sonny Rollins. Well something must have happened. It reminded me of railway tracks. The bass player was the tracks, and the drummer made the cross ties. With the sax swooping down like a fucking great firefly. And I laughed and laughed. And then thought, “What have I been doing for five years?” I had been wearing the right ties, and having my lapels out the right way – learning to say “man” and stuff like that … But for the first time I UNDERSTOOD. So then I sat down and worked on getting my cymbal time right.

Back in New Zealand, did life carry on much the same, working in a warehouse by day, and being a drummer by night?

The music always comes first. I got to the stage where I went and hired a house up in the Waitakeres, where I could take my stereo and drum kit to practise. The milkman would come by at 3am, to see this crazy guy working out snare drum and bass patterns, in total dedication. This is all so at the weekend I could go down to The Jolly Farmer to play ‘Black is Black’. So one day I thought fuck this, I’m going to Australia. The plan was for the wife and kids to stay behind, while I sorted this music thing out. I had read somewhere in the Bible about the chopping off of rotten branches. You see the whole family was always set up around Charley the drummer. But after a couple of months they came over anyway. And I’ll tell you why I gave up playing – I had these friends in Australia, in a band, and they asked me to play with them, but in addition to another drummer. The idea was, I was to just play toms. And the other drummer would hit something different, on this particular tune and both would meld into a nice fat rhythm. Well I couldn’t handle that. They wanted me to do what any fucking idiot could do. In a way it summed up my attitude towards music. Whatever it was you could do, wasn’t what you should do; because that should be something difficult, if not impossible. Anyway, to keep body and soul together I worked on the General Motors assembly line for three years.

We returned here in 1975. Murray McNabb and Frank Gibson were playing in a band called Dr Tree, which is a fucking silly name, but they asked me to organise their business and be their manager, so we move into the part of my life where I became an entrepreneur. I enjoyed writing the letters, and pushing the band here there and everywhere – on Monday nights we would fill the Globe, using the PA of a young band called Hello Sailor. While this was going on, I was working in a warehouse in Anzac Ave – doing all the right things, respected in my job, going to meetings with the boss and collecting a lousy $85 a week. I mean for me to buy a flagon of wine would break the bank. There was just no spare money. So I thought gee, if I am so fucking smart … why don’t Ann and I get a place and do what we want to do?

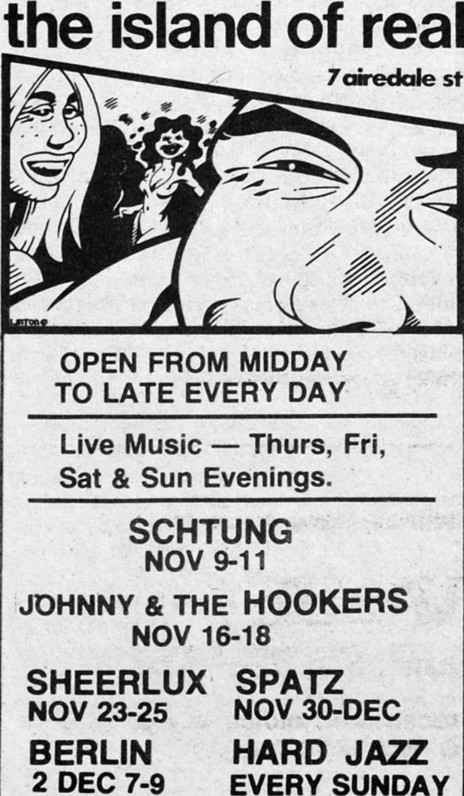

Is that The Island of Real? Who dreamed up that name?

Ann. It was a bit of a mouthful, but it worked. Most everything I have done, has been what I like, or what I want to do, and I figure that other people will come to like it too. It is a personal thing. When Ann and I lived in London, and we were both working, we pooled our money towards three entities: Ann, me, and my career. If we were short on money, but there was a new Frank Butler record out, well we just had to get it because of my career. I was justifying dope like that in those days too: “… I’m doing it to research this new Wilson Pickett record!” That sort of thing.

But The Island of Real. That place had been an old printing works, which we got from the City Council. I went in there one Christmas Eve and set to it with a crowbar. It took six months to set up, because we were so inexperienced. We didn’t realise that it would have been better to have paid a tradesman than to stuff around trying to do it ourselves. We sold the car for finance. When we first opened, I would walk to the markets, then grab a taxi, with arms full of tomatoes and lettuce and stuff.

Advertisement for the Island of Real, Airedale St, Auckland; illustration Barry Linton – Rip It Up, 1978.

Did you see it as a band venue in those days?

Not at all, it was just a coffee bar. The back room was even roped off. We were just doing lunches and stuff. We were really famous all over town for our filled rolls. People would queue up to buy them. I fact it wasn’t until some time later when my son gave me a calculator for my birthday that I worked out we were losing 20 cents on every one that we made! But we always wanted to put on bands and theatre and such, then one day this raving idiot whose major claim to fame had been to stick up a post office somewhere, suggested that we use a bank loan to open the band room. So I built a small stage, then the night that Th’ Dudes supported Peter Frampton at Western Springs, a carpenter came in and built the stage that lasted … until you bought the place.

Yes. In hindsight, why did you sell the place?

Basically because we were tired. We had had it for three years, and I was then into doing other things, like Muchmore Music Agency. Besides, the music scene was very rapidly changing. Places like Zwines and Rock HQ had started up. If The Island of Real was Auckland’s rock kitchen, then Zwines was its toilet! And speaking of which, Ann once went in to our “Ladies” and there was this girl who was probably a prim and proper little shopgirl during the week, attacking the bloody bog with a hammer. By this stage Zwines and Rock HQ had had enough, and groups like Country Flyers and Living Force weren’t where it was at with the crowds any more. We were most relieved when you bought the place and made it XS. I didn’t like the colours that you painted it though.

You were managing one of the country’s top bands, Th’ Dudes, at this time. How did that come about?

We had had them play a couple of times on a Sunday afternoon and Peter and Dave suggested I manage them, but I had turned them down. They seemed to have all the work they needed without me. I remember taking my lawyer, David Gapes and half Th’ Dudes to lunch at Raffles so we could work out a sort of bill of rights. One of these was that I would make no more money than any individual member of the group. Well, it ended up costing me money but we won’t go into that … Peter Urlich may have more stretch marks than me, but mine go deeper!

Charley Gray and producer Rob Aickin, flanked by Th' Dudes, New Zealand music awards, Parnell, 1979. - Jocelyn Carlin

Was the relationship between you and Th’ Dudes always great?

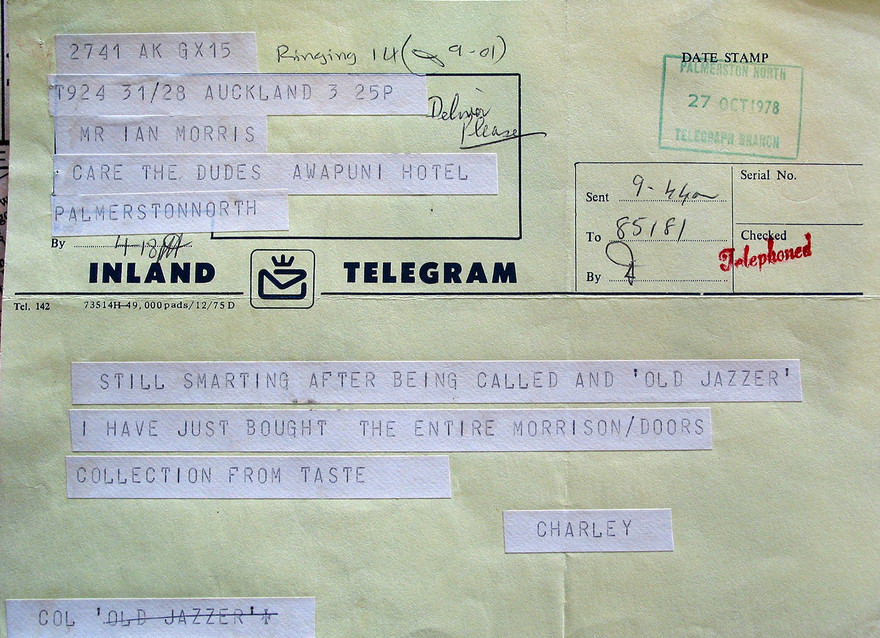

Not always. But when it wasn’t, there was always a good reason for it. For example once when we were on tour, eating dinner in the kitchen of the Awapuni Hotel, I was putting forward my ideas of how Murray McNabb and others who I believed knew music could help Dave Dobbyn. Well of course he didn’t want to know, and as it turned out, he was perfectly right, but in those days I just thought he was being blind to possibilities – and that is when they first saw the rage I was capable of.

Telegram from Charley Gray to Ian Morris at the Awapuni Hotel, Palmerston North, 27 October 1978.

Why did Th’ Dudes break up?

Ann blamed me for the demise of The Island of Real. I wouldn’t put Th’ Dudes in as they were too big to work there. She said I was dumb, and cutting my own throat. Anyway. From the very beginning they had had this inbuilt destruction factor. And I don’t blame them. Once we didn’t do a job in Tauranga, because the fucking crew didn’t think it was in the band’s interests. They aren’t the ones who are responsible for the overdraft. And one day the phone rang, and Peter said he couldn’t be bothered making a rehearsal, in fact he thought maybe they should actually call it a day. We had been to Australia to support The Members, yet when we returned, everyone thought we were returning because we weren’t good enough to hack the pace or something. There was one last weekend at The Windsor which was a disaster ’cause everyone was listening to Hammond Gamble by that stage anyway.

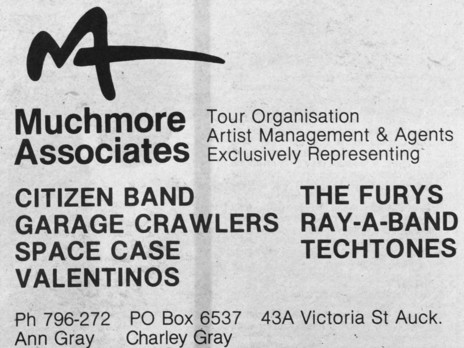

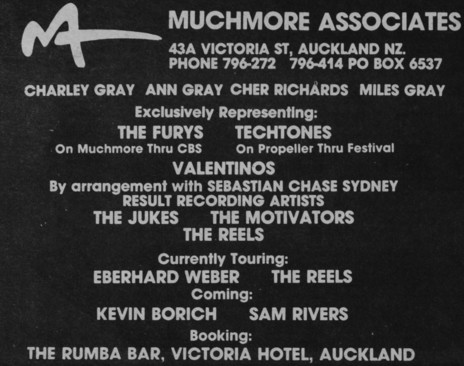

You were involved in Muchmore Music Management too – did that work?

Muchmore was a direct result of my Island of Real experience, plus seeing how efficiently Chris Murphy ran The Members tour in Australia. Tour itineraries, etc. That is the way you do it. I set up with Brian Jones. He was managing Hammond, and I had Th’ Dudes. Plus Citizen Band. Yet before we even got into this office, we had a phone call from Russell Clark asking what we thought we were doing. He maintained that he was the big international company: that his firm was doing already what we wanted to do and that there was really no point in our even starting up. Ha! Where things crapped out though was Mike Corless would go behind our backs to Brian and say, “Gee mate, if I need Hammond Gamble in Hamilton, I don’t really have to go through your agency, do I?” So it all collapsed. Then Th’ Dudes broke up. Citizen Band went to Australia, and Brian pulled out. Mind you, the Rumba Bar was pulling in some $100 per week for us, so that kept the office open. My son Miles was running that – but then he wrote off my car and I learnt my wife was dying – and I would be walking in and out of town trying to care of all these things.

Muchmore Associates advertisement, Rip It Up, 1980.

When did you first learn that Ann was dying?

I really can’t remember. I mean no disrespect to Ann, I just can’t remember dates.

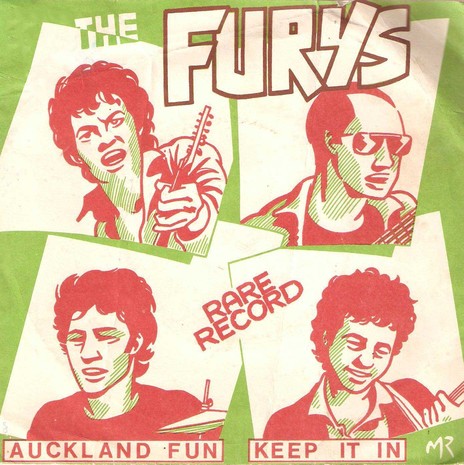

It happened the day Chris Murphy came to see Th’ Dudes. We took him to No 5 for dinner. Ann had come home from the doctor very upset and said they had told her that she had cancer. But we sort of glossed over it then, and went out and had a fantastic evening. We had been to our doctor in Herne Bay one day, and he had sent her out to the car, taken me aside, and told me he should have realised earlier that she had a really bad dose of cancer. But they gave her treatment and told her on a scale of 1-10 she was only a three, so no problem. But I think, really, you could have inverted that – one day at the hospital a doctor said to us, “Mrs Gray you have a problem that we can do no more about, because it is terminal. You have to consider every day that you have left to be quite special.” And the amazing thing is that while she was dying, she became more concerned about me. She saw herself as a controlling factor, and said, “Who is going to look after you and the kids?” Maybe it is because I was doing more crying than she was. She knew I was groping to be successful one way or another – my life had had so much drama. I didn’t really want people dying all around me. I mean the same week as we are told Ann is dying is when Miles – without a driver’s licence – is hit by a bus in our only vehicle. Right on the door. Another foot back and he could have been killed. Ann dying had a bad effect on Miles. I handled the grief in my own way – in fact I hurled a colour TV out that window in an explosion of rage which is really just an outlet of emotion. After Ann was admitted to the terminal ward of Mater Hospital, I resolved that the day she died, I would do a hugely successful deal for The Furys … I didn’t of course, I blubbered all day then went out to a licensed restaurant with friends, and got totally pissed.

The Furys’ 1981 EP on their manager Brian Jones, and Charley Gray's Muchmore label; illustration Barry Linton.

Was Muchmore still running – albeit down?

Yes. After Ann died, I moved into the office here, which was good for my soul: living alone again. Anyway, getting back to the end of Muchmore, Sam Rivers, a legendary American sax player who was in Australia with a trio, was going to come to New Zealand. So Murray McNabb said that if I put them on, he and Frank Gibson would split any losses with me. Their night at The Gluepot was, to my mind, one of the most amazing music nights in New Zealand history. We only made about $15, and we blew that taking the band to Raffles. But next we brought over Eberhard Weber – and we actually made some money on that one. However another jazz tour by Old New Dreams – who had been the heroes of the western music world for some 20 years – could barely pull 290 people into the Maidment Theatre. The one that killed us though was Snakefinger. We were to pay the band $100 a day in their hand. We had booked into the Maidment, the Gluepot, airline tickets and motels up and down the country – then when Snakefinger came off stage in Melbourne, after a sell-out show, he had a heart attack. And that was the end of Muchmore.

Muchmore Associates advertisement, Rip It Up, 1981.

What you got you back on your feet?

I looked out the window here one day, over at the Royal International Hotel, and came up with a deal to their manager with a view to putting American jazz musicians into the Grotto Room. Well he came up with another proposal over my running the pub’s accommodation. I wasn’t particularly interested – this is just before Christmas 1981, and Miles and I were going to Brazil. But he persuaded me to try it for a bit and gave me a salary plus food and dry cleaning expenses. However the figures didn’t come up to scratch, so we negotiated out again.

Why did you want to go to Brazil?

I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say I am a passionate man. I feel things strongly. I’m sensitive to some degree, and I wanted to go somewhere where people are people. And in Brazil the sunlight is incredible. I had also been listening to Brazilian music. Jorge Ben. Rod Stewart had ripped off one of his songs, and the guy had sued for millions of dollars, and got the money. Brazil is a fantastic place. We had this fantasy that we wouldn’t come back. I could stay there and write. It is important to realise that things for me are continually ongoing; I mean someday I would like to bring Pere Ubu out here to tour and say, “Take that New Zealand”.

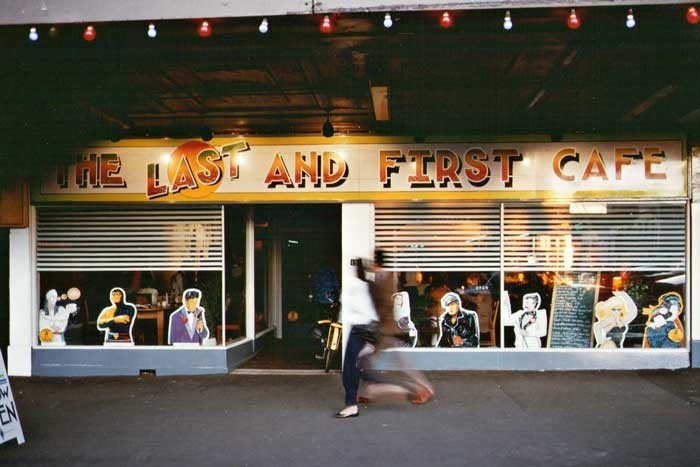

Finally, The Famous Last and First Café …

I came back to New Zealand, moved back into the office, and read a lot. And ate in restaurants. Every time I went out to dinner it would cost 30, 40, 50 bucks. The saving grace was Le Brie at $15. Then someone suggested John’s Diner. I liked that except the food kept repeating on me. It reminded me of a place in London I used to go when I had a spare quid, called The Fiesta. It was run by a West Indian guy who would play Ornette Coleman records, and yell out, “Watch this guy, he’s gonna be big!” Anyway I had to do something, because I was running out of money. So, I thought I would open a café, and do the cooking myself. To cut a long story short, I found these premises in Symonds Street, and got Peter Campbell – who had worked for me at The Island of Real – back from Australia, and offered him a partnership. We opened on fuck-all money, a lot of hard work, and the grace of the bank manager. And from day one, it went crazy.

Charley Gray’s Last and First Café, Symonds Street, Auckland, 1982 - Simon Lynch

What do you feel about the late night cafés that have sprung up in your wake?

These people would openly come down to check us out, sitting there taking down notes and costings. But the difference is we are a restaurant with nearly a million dollar a year turnover. We can’t afford to cater to just one form of clientele. We are there for all sorts, from [Metro founding editor] Warwick Roger in his black leather and studs, to [politician] Jim Anderton with his kids. You see people have been following me around for years. Ann would see them at The Island of Real – people would actually come up and say, we can do this bigger and better, and we will take all your customers. Ha! Good luck to them. I mean, I need somewhere to go at night myself.

--

In 2010 Charley Gray was interviewed by Kim Hill, talking about the 25 years after the ChaCha interview, covering his years running the art-house cinema, and his time in Australia. The audio is embedded below.