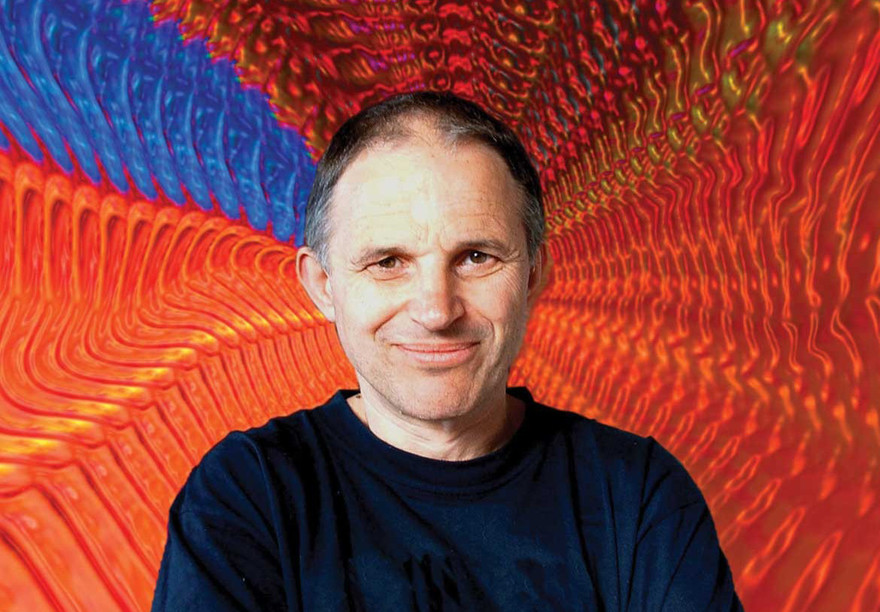

Chris Knox in 2005. - Simon Grigg Collection

Part three of a conversation between Gareth Shute and Chris Knox from early 2007 (read part one and two here). We are publishing this transcript in full so fans, researchers and writers will have access to his raw reflections on his life in music and better understand Knox’s important role in the New Zealand music scene.

--

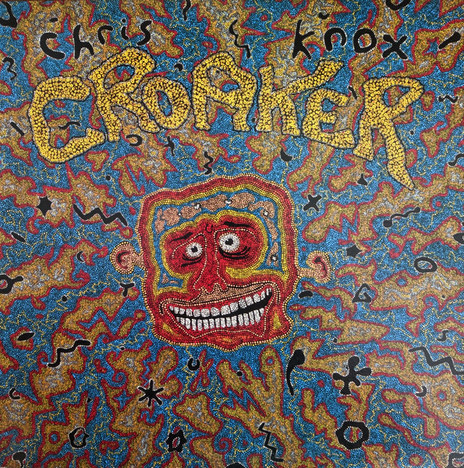

It seems as if from 1990 to 1993, you had this really prolific period. Two solo albums – Croaker (1990) and Polyfoto Duck Shaped Pain and “Gum” (1993) – and two full length Tall Dwarf albums – Weeville (1990) and Fork Songs (1991). Was there a particular reason behind that?

I don’t why so much was coming out. I was enjoying the solo stuff and I was doing a lot of writing I guess, because I realised I could do it by myself. All the Tall Dwarfs stuff was just written while we were recording, so that didn’t take any time out of the solo writing, so it was just really easy to do both. And yeah, it did seem to be pouring out. It was really good fun going down and recording with Alec [Bathgate] or him coming up here, because we’re best mates and we don’t get to see each other much so it’s a good excuse to see each other.

Were you trying to do different stuff with the solo work?

It wasn’t really a matter of trying, it was just the way that it was. My solo stuff was all pre-written and the Tall Dwarfs stuff just came out of the ether, so it was always different. Alec was a real musician so that made a difference with the Tall Dwarfs stuff. Tall Dwarfs was lyrically generally different because a lot of my solo stuff was about things that concerned me. The Tall Dwarfs were more about things that were not about me but were about things that we both felt enthused or amused or abused by.

Croaker seems particularly unusual in how tender it is, I guess because it has cello parts and has a few quieter moments on it. How did that come about? Did you just see after Seizure that you could go further in that direction?

There was gentle stuff on Seizure (1989) as well but it was overshadowed by the noisier things – one, because they were more obvious and two, because the noisier things were recorded in an actual studio and they sounded better. But yeah, on Croaker I guess there may have been more of the gentler stuff. Apart from anything else, I was recording at home, so I wasn’t able to get the big sounds that it was so easy to get in a studio. Yeah, it was just a different feel. I suppose it was a year on and you’re writing about different things because different things are going on in your life.

Chris Knox - Croaker (Flying Nun, 1993)

Around then, you also did the first Tall Dwarfs overseas trip?

Yeah, and that was great because the first gig was in San Francisco and there were 800 people. We couldn’t believe it. We were headlining. “800 people in San Francisco? What? That’s crazy.” It was fantastic. I didn’t sleep for quite some time on that tour, but apart from that, it was brilliant.

Most of the time when you were back in New Zealand had you found it quite hard to tell how well you were doing overseas?

“There were bands around that were namechecking us as inspirations, which was very cool.”

Absolutely, though we were getting more and more mail, and seeing more and more reviews, and so forth. We were also finding out that there were bands around that were namechecking us as inspirations, which was very cool. Other Flying Nun bands as well. So yeah, our heads were getting quite swollen really.

The band was quite popular with NME. At what point did it feel like they really cottoned on it. Would that have been in the late 80s?

It was probably around the time of the first compilation, but I’m not at all sure. I wasn’t really interested in the English scene at that point, to be honest. It didn’t seem… [Chris is suddenly distracted] ... Yay, I won, I got Yoko Ono’s Fly double album for nine bucks American. I’ve been after it for bloody years.

In 1993, you did a solo tour supporting Yo La Tengo. Then after that, you toured with them as the Tall Dwarfs.

Possibly. Me or the Tall Dwarfs certainly did several go-rounds with Yo La Tengo. Which has become completely confused in my head. But I do know that it was probably that solo tour that you’re talking about when they made me buy a guitar tuner because they were just so sick of my guitar being out of tune. The only shop that was around was just closing and I actually had to physically go under the roller door as they pulled it down and I ended up buying a really crappy tuner. You get that.

Pavement and Superchunk seem to be the other ones that regularly namechecked the Tall Dwarfs?

Yeah, I ended up playing with Pavement several times when they came over here and that was fun because I hadn’t realised they had that debt to us. As far as Spiral Stairs [Scott Kannberg] was involved, we were right up there with The Fall. I also toured with Superchunk. I can’t remember if it was Tall Dwarfs or solo – I think it was Tall Dwarfs. It transpired that the Merge [label] types had that Tall Dwarf thing going too so it was really nice to actually meet these people and have a little adulation thrust upon us.

How did you find your deal with Homestead in the US worked out in the end? A lot of the American bands later said that they had trouble being paid out, not because of Gerard Cosloy [label manager at Homestead] but because of [parent company] Dutch East India Trading?

We heard all about that and when Gerard left, we lost interest in the label really. It didn’t really affect us because we were so used to not being paid for records, so to be not paid for another one was nothing remarkable. Gerard promised that Matador would release our stuff but that was a hollow, tragic promise – it never came to anything.

[Matador was founded by another ex-staff member from Dutch East India Trading, Chris Lombardi. Cosloy joined him as a partner in the business in 1990. Matador did release Yes by Chris Knox in 1990, but never worked with Tall Dwarfs.]

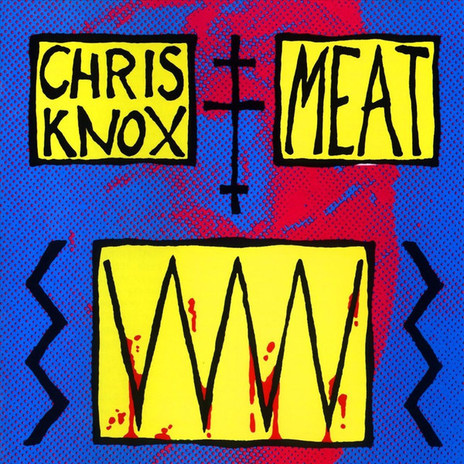

Chris Knox - Meat (Communion label, 1993)

You did a later album through Communion?

Yeah, I did an album through Communion and that was really cool. Gary Hell was extremely cool. Meat was a compilation of the first two albums, plus one song off Guppies that he insisted go on there. He was a sweetheart but unfortunately we fell out because I pulled out of a tour with Smog – not at the last moment, but I could have handled it more gracefully. I was just terrified of travelling at that point because the last time I’d been there I hadn’t slept and I was going to have to go over there by myself and do these long 12-hour drives between gigs, though I would’ve been driven by someone else because I don’t drive. It was just like – I’m not putting myself through that again. Though it would have been great because I get along really well with Bill Smog – Bill Callahan.

You did the Fast Forward Festival in Holland with him as Tall Dwarfs in 1994 and then undertook a small tour with him as the support act?

Yeah, that’s right. It was really really interesting because he was the shyest person on the face of the planet at that point. I’ve never met anybody like him, but he was singing these dark bleak little songs, stripped right down to the core. At the time he was touring with this girl who played guitar and sang a little bit, but she’d only played guitar since she’d met him. I’ve completely forgotten her name, even though I know it really well.

That was the tour during which the Tall Dwarfs were supported by Green Day?

We were playing in Cologne in this little club. We got there and found out that we were being supported by this young American band who’d just been touring around the UK. They’d come direct from England and that night they had to get the ferry back after playing – straight back to the UK to recommence their tour. Their tour manager had done a real bad job. They were playing these tiny little dives for bugger-all money, supporting these non-entities like ourselves even though they were Green Day and Dookie had just come out and gone triple platinum or whatever, but they were stuck – contractually obliged to do this series of gigs.

So, this tiny little club was just full to overflowing when these guys got up and played. It was amazing because they were just absolutely zoned out – lying on pool tables, any flat surface they could find – they were just absolutely shagged. But by the time they got up to go onstage, they put on an amazing punk show. They were really really good. It was great to see them in that little room. Then as soon as they’d finished, they just dived in the van and got driven away. And that was that. We got on and at least half the audience left. We just said, “wow, I’m not sure what just happened, but hey, we’re the headliners”. It was an experience.

It was nice to see that. One, a big band who had obviously got big really quickly, could still get fucked over, it wasn’t just us little bands that were being fucked over; two, that even though they were being fucked over, they had the ethics to continue with the tour and not pull out of it, so good on them; and three, that they could go from completely comatose to the most alive energizer bunnies in the world onstage at the flick of switch. They were definitely pros before they got famous.

Were there points in your own career when you feel like you’ve been fucked over?

Just tours that are routed really strangely. Like when The Clean and I first went over to Germany, we had to go down to Frankfurt. It was a six-hour drive just for a bloody radio interview that we could’ve done on the phone. I mean, that’s fucking you over.

By the time of your solo tour in 1995, you had enough money to bring Barbara [Ward] over for the tour and still had enough money left over to buy a car for you guys?

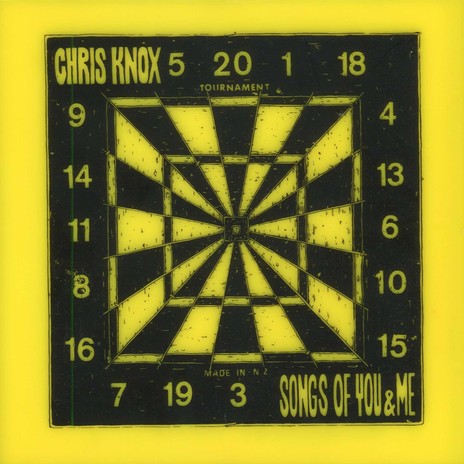

That’d be a $5000 car, just for the record – we’ve never spent more than five thousand on a car. I think that would’ve been the Songs Of You and Me tour. At that point, I was the taste of the month. At one point, I was number one on the college music journal radio charts and Songs Of You and Me did remarkably well.

Chris Knox - Songs Of You & Me, (Flying Nun, 1995)

Who put that one out?

That was through Caroline and dunno how that happened. I just got word from them that they would like to do an album and did it.

Do you think that was bigger than Meat?

Yeah, I think so. It got a lot of push, and it got a lot of coverage. It went to the tops of charts and things like that. God knows why, it was a great big ugly sprawling thing. The cover helped I think – the fact that it was unusual. It was a screen-printed dartboard on an opaque yellow jewel case. It leapt out of the shelves at you. It was the only time that I’ve really been part of that machinery, where I’ve had to do 18 interviews in a day and that sort of thing. It was really interesting.

Did you have interest in the UK at that time or had your career mainly moved toward the US?

4AD were quite interested and Ivor Watt Davies – the guy who founded and ran the label – did a cover of one of my songs on the Hope Blister album, which unfortunately sold bugger-all. That was about the only interest out of England.

How was the balance between Tall Dwarfs and your solo career at that point?

It was pretty equal. I was doing more solo gigs because they were easier. We didn’t have to practise and get each other from the other ends of the country to join up and so forth, but as far as recording, it was pretty much Tall Dwarfs one year and solo the next year for a decent chunk of the nineties. That’s eased off a lot recently, but I still think of the two threads as being equal in value and importance.

You did more tours overseas during the late nineties? Including a tour supporting Ween just after you released Yes (1997)?

Yeah, either with Tall Dwarfs or I seem to tour once every 18 months or something. Again, that’s slackened off. I haven’t done a full-scale tour since 2000. Tall Dwarfs went over to France for a one-off thing which was just two gigs, but that doesn’t really count.

That was the festival where you had to share music with the other artists?

That was interesting. It was in one of those spiegeltents, like they have at the Auckland Arts Festival. It was a wooden tent lined with mirrors, in a little courtyard in a northern French town that nobody ever wants to go to, called Arras. It was the arras-hole of France. It was awful.

It doesn’t even have a cinema.

Oh, you read that? Yeah. 40,000 people and no flicks. Crazy. It was interesting in its own way. I met some nice people and did some interesting collaboration, but it wasn’t what we were expecting. Not only were we playing in a circus tent, but we had a ringmaster controlling our every move. We thought we’d just jam, but no, we were forced to compose and play on each other’s songs. It was very odd.

Dylan Taite interviews Chris Knox, the 2000 Silver Scroll winner with 'My Only Friend'.

Then there was the Olivia Tremor Control tour in 2005. That also coincided with reissues of Weeville and Fork Songs, which came out on Cloud Recordings, the label owned by John Fernandes from Olivia Tremor Control ...

Sorry, yeah, we have done one tour since 2000. How could I forget that? That was amazing. There were about 12 of them and they all played everybody else’s instruments, they’re like a Lil' Chief band but even weirder. They were great gigs. We generally got reviewed very badly because there was just the two of us and people had expectations of something like Olivia Tremor Control I think, and they were much more musicianly than we were. They got longer soundchecks. But it was great fun, met some interesting people, and saw good old Jeff Mangum [Neutral Milk Hotel] do his thing with them. He did a couple of songs during two nights in New York. We tried to get him up to do ‘Nothing’s Going to Happen’ because he knows the words better than I do, but the little bugger chickened out unfortunately.

Did you still find you had an audience over there? I mean obviously it was their gig.

Yeah. It was their gig, but we still sold quite a lot of merch, I did lots of drawings for people, and we had people doing the “oh my god, you changed my life” spiel. “May I have your children?” “Well, yes, but they’re quite old.” But because we were the support act, Olivia Tremor Control were getting more of that than us, but did we feel bad? No, not at all.

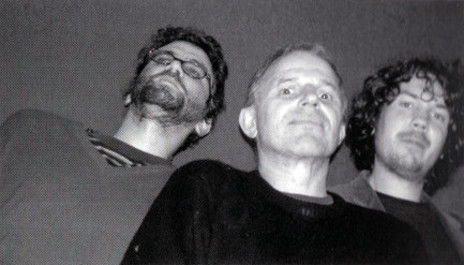

Chris Knox and The Nothing, with Stefan Neville at left and Jol Mulholland at right.

How does your approach differ now? I know recently you’ve done an album with a band in a studio [as Chris Knox & The Nothing]. Is Tall Dwarfs still on tape or do you use digital recording?

No, the last album we did, we started on tape and then transferred to Pro Tools, because I bought Pro Tools halfway through the process. I edited it all on Pro Tools and did overdubs with it. The next one will be on Pro Tools too because Alec has it down in Christchurch and I’ve got it up here, so it just makes complete sense. This will hopefully be this year.

When was the last one?

The Sky Above The Mind Below in 2002, so it’s been a while. We need to do another one. Five years between Tall Dwarfs albums is too long. Alec swore never to do another solo album, because he hates the process so much that the only way to get Alec out there on polycarbonate is to do a Tall Dwarfs record.

[Alec Bathgate’s two solo original solo albums and an instrumental album from 2020 were reissued on vinyl in 2022 with distribution through Flying Nun.]

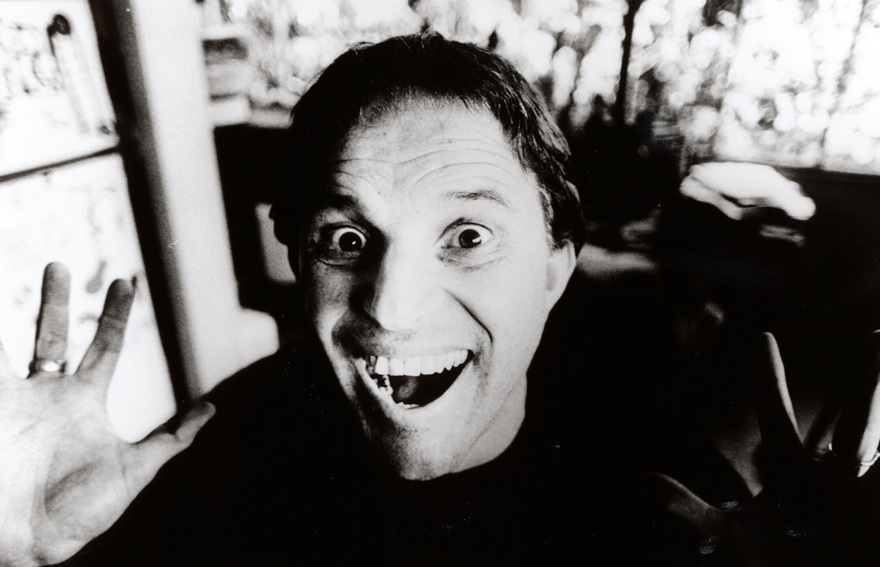

Chris Knox in a promo shot for the Beat album, 2000.

How do you find it looking back, when you compare your career to bands that went the major label route? Like The Chills working Warners via Slash Records and Straitjacket Fits working with Arista? Whereas The Clean and Tall Dwarfs kept being …

Tiny? Insignificant? No, it was good. We’d had the big label experience, so we weren’t curious about it. We knew it was slimy and horrible so didn’t see the point. Whereas those guys hadn’t been with WEA or whatever. We had, so we knew what to expect. It was purportedly better then than it had been back in Toy Love days but, even so, it seemed like a better thing to have complete control of your destiny, even if you weren’t very good at doing anything with that control.

At least you knew what was happening to a great degree, rather than just letting yourself be taken over by some big corporate beast that didn’t really give a shit who you were and what you were doing, only that you were selling units. So, I can’t blame those guys for what they did, but I don’t think any of them came out of it any musically better. They may have made a few more bucks on advances and so forth, but Straitjacket Fits died while working with one of those big labels. The Chills died in similar circumstances, even though Martin would protest that and say “no The Chills are better than they’ve ever been”. But recorded evidence doesn’t support that.

A self portrait. - Photo by Chris Knox.

You weren’t tempted in 1990 when you had that overseas interest and The Chills were in NME every week?

Nah, I wasn’t tempted by any of that stuff. It was fun being able to go overseas to play and have a credible, small-major (or a large-minor) label look after your interests, such as Homestead, Communion, Caroline. The last one I had anything to do with was ... I do have a memory somewhere. Two words. Isn’t it pathetic, I can’t even remember the label that released my last album that went out domestically in the States. First Ear.

Which album was that?

It must have been Yes. It was Yes.

[It was actually the album after this, Beat (2000), which was released on Thirsty Ear, but Chris was close!]

Since then, you’ve done the album Friend? Was that a complete studio album?

Yes. Friend was just me and the computer – purely and simply - and a bunch of cassettes of found sound. Friend was the name of the artist and Inaccuracies & Omissions was the name of the album. One of those words was spelled wrong so be careful. It was maybe inaccuracies, I guess. Maybe I left a letter out of omissions if I was being really clever.

Was that the noise album?

Yeah, found-sound manipulated like mad.

You did one on the end of Yes as well, didn’t you?

Yes and nobody got it. It was spelt ‘N D I D I’ and it was on the end of the Yes album. Yes-indidi.

Indeedy! Just to finish, it would be great to get a sense of your perspective on some of those other early artists – Shayne Carter and Martin Phillipps.

Shayne reminded me of me to a degree, in that, he was a really pushy, stroppy obnoxious frontman and he pushed the envelope musically, especially while being pretty out of it on stage. He was laceratingly funny between songs, as was Wayne Elsey in Doublehappys – they were a wonderful pair. He was instrumentally way more talented than me and wrote more complex songs, but I felt a real kinship with him. I was never a huge Straitjacket Fits fan, I actually like Dimmer better than the Straitjacket Fits in many ways, but I just really respected what he did and what the band achieved.

Martin was a whole different kettle of fish. He was a kettle of fish actually! That’s as good a way of describing Martin as any – he was one out of the box. He was a unique little person, though he eventually became taller than me, though I did know him when he was shorter. He was much more concerned – not so much with the moment, but with the legacy. I think that was the big difference between Martin and virtually anybody else on the label, with the exception of Sneaky Feelings. He really wanted to go down in history because all his heroes had done. He was the only one who seemed to follow templates, even though his music was entirely individualistic. In terms of behaviour, he seemed to want to emulate his heroes right down to the drugs that they took and so forth. He was a music scholar with a real good way with a tune, whereas Shayne wasn’t nearly the music scholar but was more of a natural musician, I think.

Chris Knox with Debbie Harry and Chris Stein after Chris opened for Blondie, Paris, 1998.

You always sensed Martin was always working hard to achieve what he did, whereas with Shayne, it just sorta slipped out, which is not to denigrate what Martin did at all, because both ways can come out with fantastic music. Just they were different. Martin was always striving for something he could hear in his head, but could never quite get down on tape, whereas Shayne trusted other people a little more to help make what he heard work. Arguably songs like ‘Dialling a Prayer’ and ‘She Speeds’ were really the sort of symphonic sounds that The Chills were after, but realised with seemingly much more ease than The Chills ever did.

Chris Knox. - Photo by Barbara Ward

But then, nobody at Flying Nun made a song as extraordinary as the last track of the Lost EP. I can’t even think what it’s called [‘Dream by Dream’] but it’s got the “goodnight Martin, goodnight Chills” thing at the end. It’s about the band breaking up, about the bass player leaving and so forth. It’s extraordinary. He had a real sense of the cinema in music, which he shared with the likes of Brian Wilson, and that track in particular was like the little fairy tale that came off the Holland record by the Beach Boys that was half-played, half-music [‘Mount Vernon and Fairway (A Fairy Tale)’].

So yeah, they both had extraordinary strengths that were expressed differently and came from extraordinarily different human beings, but yeah – equal talents, arguably.

At what stage do you think your own stage persona changed?

“At that point, I stopped being angry onstage and just became as funny as I could be.”

I don’t know the date, but I was playing a Tall Dwarfs gig at Sammy’s in Dunedin. Always Dunedin. And I got really pissed off with the audience, who were all sitting cross-legged on the floor and sending back no energy at all. As a performer, the more energy an audience sends to you, the more you can give back to them, which makes a great gig. It’s really hard doing it to a bunch of people sitting on the dance-floor cross-legged. I got really pissed off and berated them at length between songs and went on about what a cesspit Dunedin was and so forth. Then on the bus up to Christchurch, I just sat there thinking to myself, “Hmm, I was right, but I should’ve expressed it with humour. not with anger.”

At that point, I stopped being angry onstage and just became as funny as I could be. I made a big decision to stop trying to be angsty and weird; to try and be really intense and make people scared of me and my music. Instead, I open my arms and just say: “nah it’s just a big giggle”. Which I’d always been doing, but the anger was always a part of it. Since that point, I’ve gone out of my way to not let the anger come through, unless the lyrics of the song need that there – but not between the songs. So now I’m much more of a clown than I ever was and that hasn’t changed. At Big Day Out a few weeks ago, I ran through the crowd, injured myself badly, got jumped on by a woman physically and we both fell onto the bitumen stuff that covered the ground, so nothing’s changed as far as stupidity is concerned.

The early Flying Nun bands seemed to do away with the whole rock star thing, as far as what you and The Clean were doing.

That distance did come with Straitjacket Fits when they started getting serious. Before that, with Doublehappys, they were very much about breaking down that third wall or fourth wall, whatever it is. But for me, there is this symbiosis that goes on which requires equal output and input from both sides of the gig equation. That’s why it’s really good when you’ve got lots more people offstage than you’ve got onstage, because it’s hard for five or six people offstage to give as much energy as four or five people onstage, because we’ve got all that noise going for us. Having said that, some of the best gigs I’ve played have been to a dozen people. If you’ve got a couple of hundred people that are going apeshit then you’re going to have a really good time. That’s when it gets into that feedback cycle where it just gets bigger and bigger, and eventually it explodes in orgasms of happiness and everybody goes home drained and happy and pleased with themselves.

Do you think you’re more down-to-earth now that you’re older?

Possibly, but I’m just that sort of person really. Even though I occasionally make very pretentious art of one sort or another, I don’t like pretensions. Possibly the only gig I’ve really enjoyed where the band was totally aloof was The Jesus and Mary Chain the first time they came here. They were utterly aloof, but I think it was primarily out of shyness. They showered themselves with dry ice and you couldn’t see them half the time, but it was an amazing gig. Mind you, they’re an amazing band, that helps. It was extraordinary.

The last time I saw a band that were pretty aloof, though not as much as that, was Wire. That’s probably up there with Brian Wilson as one of my favourite gigs of the 21st century. So, you can do that too and get away with it, but it’s harder. People who actually relate to the audience – where you can sense their humanity – they’re just one step ahead. Well, for me, anyway. Some people just like hearing the record really, really loud with people playing onstage, but I hate that.

--