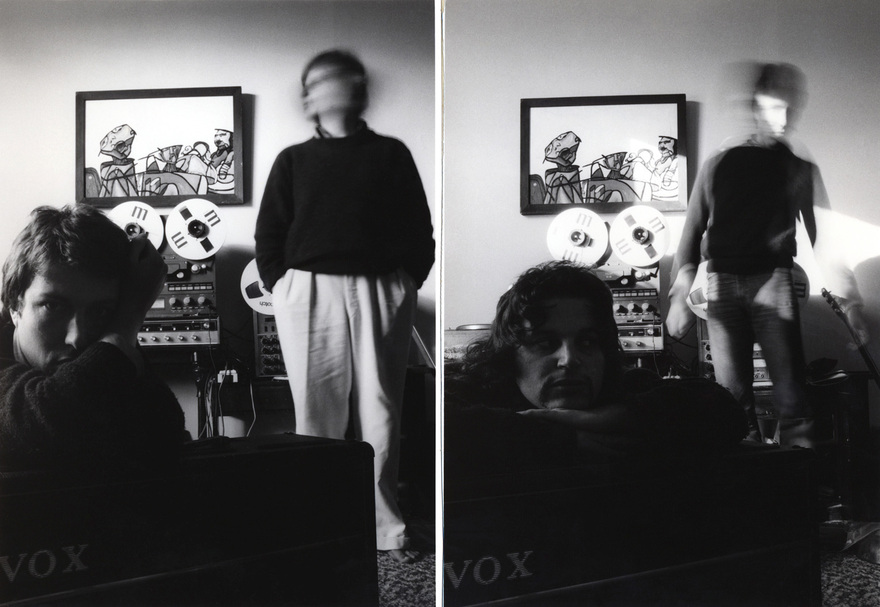

A 1998 Tall Dwarfs publicity shot. - Photo by Jono Rotman

The following is part two of a conversation between Gareth Shute and Chris Knox from early 2007 (part one is here). We are publishing this transcript in full so fans, researchers and writers will have access to his raw reflections on his life in music and better understand Knox’s important role in the New Zealand music scene.

--

Toy Love’s breakup is well covered, but can you tell me about the decision to move on to Tall Dwarfs?

We’d had a pretty unfortunate experience recording the Toy Love album in Australia and we never wanted to repeat that. When we broke up, I was pretty bereft really, because I’d gone from being the centre of attention amongst a whole lot of people and being onstage all the time and having a whole bunch of fun, to being with Barbara [Ward] underneath a house in Grafton Gully. She was pregnant and it was just such a huge change. My grandma died and left me a little bit of money and I bought a four-track and started mucking around with that. Alec [Bathgate] was around and everybody else had disappeared, so he and I started doing some stuff. He was living in Auckland at that stage. We had this riff left over from Toy Love. A three-chord riff. Well, two chords really. We always thought it would be a great rock anthem of some nature so that was one of the first things we tried to put down. That was the song that everybody likes … that the Tall Dwarfs did on their first record …

Tall Dwarfs, 1983 - Murray Cammick Collection

‘Nothing’s Going to Happen’?

‘Nothing’s Going to Happen’, that’s the one! The first recording we actually did was ‘Luck or Loveliness’. That was hilarious because we had 12 layers of recording on that song, which on a four-track is a pretty interesting procedure.

Bouncing and bouncing and bouncing?

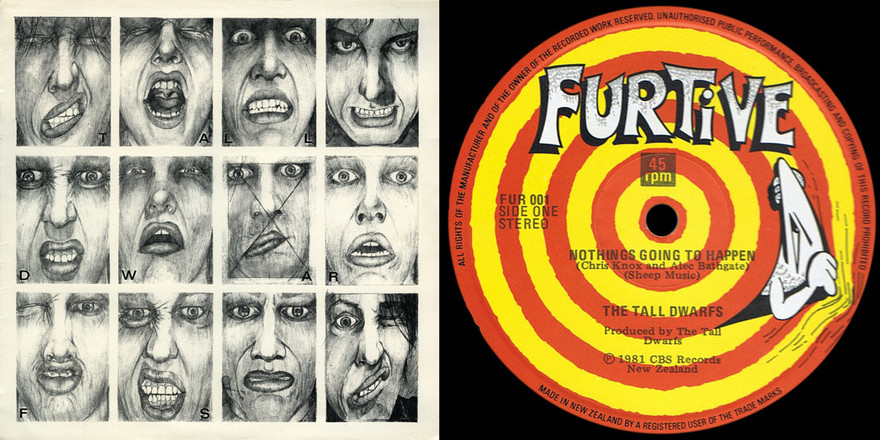

Yeah, bouncing and bouncing and working out from the beginning where something is going to end up on the stereo input at the end. It’s no mean feat. So, we were really happy with the recordings we did. They were released by Furtive, which was Paul Rose and Simon Grigg.

Tall Dwarfs - Three Songs (Furtive, 1981)

At what point did Alec move back to Christchurch?

I really can’t remember. It must’ve been just after that EP. I think that was the only one we did while he was up here. So, I’d say about ’82 or something. But it was marvellous because we just realised that we could get all those sounds that we really wanted, that engineers never let us have in those whoop-de-do studios. It was great fun. Just one mic and our mixer was just a thing that routed things left, right, or centre. No EQ or anything. Just bang, bang or bang. So, it was learning from a very minimalistic point. It formed the music we made from there on in.

What was the idea behind not getting a bassist and a drummer? That would’ve been quite unusual at the time?

Bass players and drummers are so hard to get along with. The bass player’s always the real muso of the group and thinks he knows everything, and the drummer is just a fuckwit, so it’s much easier to be without them.

Tall Dwarfs, early 1980s. - Murray Cammick Collection

So, a lot of it was just banging on a table or whatever?

We had a multi-track so we could do rhythms ourselves – just bashing on a guitar case or a cardboard box or whatever. I mean some of the best records ever have been recorded with rhythm tracks like that. Buddy Holly and The Beatles have done tracks like that. Yeah, bugger it, we don’t need a drummer.

So when you talk about “tape loops”, you mean actually physical loops of tape?

Yeah, we could’ve got some indentured slaves from the north to play them through for us instead. But yeah, they were just a loop of tape with a piece of sticky tape. I’d heard them years before and had always been fascinated by the idea. It was like – “yeah, they can be our drummer, woohoo”. We didn’t really use them until the third record. Before that any percussion was live percussion in real time, but it very quickly became our rhythm section of choice.

That would’ve been Canned Music?

Yeah, Canned Music had ‘Turning Brown and Torn in Two’ with the “wuh wuh wuh wuh”, which was just exactly that, looped for a rhythm. From then on, we just said – “let’s do this more and more and more”.

Once you loop it, do you record it back onto the four-track?

I must’ve done them on the two-track, because I had a two-track by then. So they would’ve been two-track loops then played from that down to [a single] track on the four-track.

It would be much easier to do it with computers now – cut and paste.

It would be easier to do with computers and every bastard under the sun is doing it. We were the pioneers, damn it!

How did you feel when Flying Nun started and those first Clean recordings came out and ‘Tally Ho’?

Oh man, we were thrilled! It was just amazing that someone had actually glommed onto The Clean and released a single. It was like – yes! Then we found out that it was Roger Shepherd who used to come from Christchurch to Dunedin to go to Enemy gigs and so forth, it was like, “ah, that nutter, that whiskey-crazed bastard! It’s him, fantastic. We even know the guy that’s running it. Excellent!” So yeah, we jumped on board as quickly as possible. Every Tall Dwarf record after that has been released on Flying Nun. Even the first one was re-released a couple of years later as a Flying Nun record. Most people think that all Tall Dwarfs releases were all on Flying Nun, but no – the first one was Furtive.

Tall Dwarfs, 1981 - Photo by Barbara Ward

How did you find Roger early on? He’s sometimes painted as the sensible bookish one, but was he more of a whiskey-drinking party animal?

He was a total party animal. He was a rager, almost to the point of insanity at times. He was not the world’s best businessman, but he managed to create a longstanding business within New Zealand so his methods must have something going for them. He certainly managed to engender enthusiasm. His main wonderful point was he let us do what we wanted to do. There was no “oh look, the cover looks a bit weird, could you perhaps tone it down a little?” There was no “that track’s just useless, do something else”. None of that. “That mix is vile” – nope.

It was just – whatever we presented Roger with, he’d put it out as long as he liked the basic musical unit, which was great. He had good taste in terms of most of the people he signed. Well, there wasn’t any signing involved. He just said, “make a record, go on”. He trusted the musicians he liked to come up with stuff that would work for listeners, and he was generally right.

Was it mainly through recording the Dunedin Double and stuff like that, which meant you got to know the younger bands? When did you get to know people like Martin Phillipps and Shayne Carter and so on?

Through The Clean really, because we had the connection with The Clean. Then through Flying Nun. When the bands came up here, they’d stay with us because we were the only Auckland people they knew. We were the Flying Nun branch up here. So, we got to know them all pretty damn quickly. We were excited to find out who all these post-Clean bands were because we’d hear from the Kilgour brothers and so forth. “This new band, The Chills, is our mate Martin Phillipps, it’s pretty cool. The Stones, you should hear the bloody Stones man, whew! They make us sound like the Doobie Brothers.”

So, we’d be hearing these rumours and we’d be getting letters from them about these new bands. It was really exciting for us. Through those connections, we got to know them really well and we liked all the music – even Sneaky Feelings, Matthew [Bannister]! We liked it all and really wanted to help them in any way we could. That transpired to be helping to record them with my four-track and Doug Hood’s expertise.

Then they’d sleep on your couch when they were up here and shoot music videos in your lounge?

Ha! Yeah, all that shit.

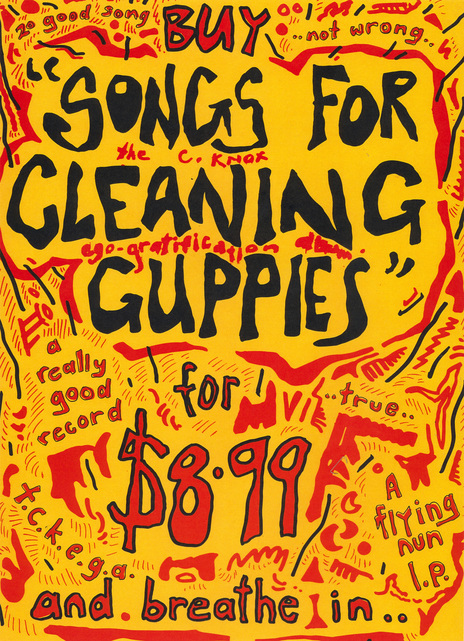

Advert/poster for Chris Knox - Songs for Cleaning Guppies (Flying Nun, 1983)

How did your first solo album, Songs For Cleaning Guppies (1983), come about?

That was just me trying to work out how to work the four-track and how to become a recordist. I’d amassed a whole bunch of tracks and had been playing them to family and friends and Doug [Hood] said, “oh, you should put these out, you’ve got a record here, you’ve got 20 tracks (or however many it was), put out a record!” I went, “come on, these are just experiments, they’re not for public consumption, they’re so stupid.” “Nah, go on.” So I did, and it sold in pathetic quantities and is now probably priceless amongst a very very small bunch of people.

Though it seems as if up until Seizure, Tall Dwarfs remained your main focus.

Yeah, the Tall Dwarfs were everything. Alec went to England, and we thought that was going to be the end of it in 1984, but then he came back and it gained a whole new lease of life. It was fun. I had young kids and Alec had even younger kids, so we didn’t have an awful lot of time to devote to music, an EP a year was just about dead right. It was always an adventure because we never had complete songs written when we started recording. We never knew what we were going to get until we were finished, which was a great way to do things.

So, the EPs were partly because of you having children and partly because of the distance of living in different cities?

It was just a really natural thing to do because we could get together for a few days at a time and have maybe five or six songs. Rather than wait for another period and get another five or six songs to make an album, it seemed to make absolute sense just to put those songs out. EPs have traditionally sold really with Flying Nun. I think it’s one of the few labels in the world – I’ve never come across another one – that made its reputation on EPs. Virtually every band who was involved with Flying Nun – early Flying Nun at least – their first EP was probably their best record, I think.

A lot of the early Flying Nun EPs also made it onto the singles charts, so that’s quite a sneaky way to get on there.

Yeah, I think it was great. It was cheap but you got a decent number of songs. It was 12" 45rpm, so you got a good sound – better sound than an album. Good artwork is possible with a 12" spread, so yeah it was perfect.

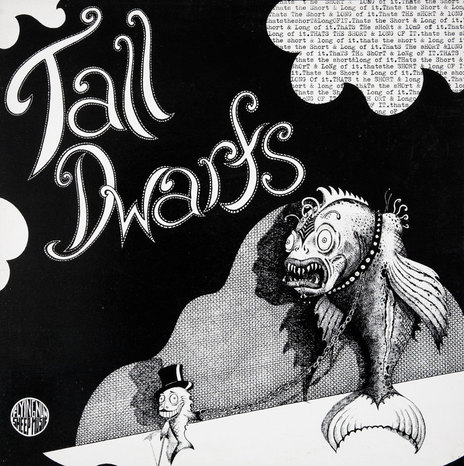

Tall Dwarfs' 1985 album That's The Short And The Long Of It. Side one plays at 45rpm, side two at 33 1/3rpm.

Was That’s The Short and Long of It (1985) the first time that Tall Dwarfs did an album rather than an EP? People talk about Weeville (1990) being the band’s first proper album?

Weeville was the first straightforward album. Short and Long of It was a 12" 45rpm on one side and 12" 33rpm on the other. There were 12 songs all together and the two songs on side one (the 45rpm side) took up about 12 minutes between the two of them, so it was basically an album, but it was just a Frankensteinian album.

When did you first feel like Tall Dwarfs were getting overseas interest? Was it right from the start?

I can’t remember to be honest. I guess it was when we got a letter through Box 677 – which was Flying Nun’s PO Box number – from someone in the States going, “wow, love this Louie Loves His Daily Dip shit, man.” Then we realised that not only was the record getting over there, but it was getting over there to people who were enthused enough to write back. Then reviews started filtering through from places like Forced Exposure and so forth. By the mid-80s, we were beginning to realise that there were people out there who were really keen to hear more. It became obvious at some point that we’d actually be able to tour and shit, which was pretty amazing.

John Peel picked up some early stuff as well.

I can’t remember to be honest. He was pretty onto everything, so no doubt he played some of that stuff.

Do you think the first big international release for you guys would’ve been the Hello Cruel World compilation, put out through Homestead in the US?

Yeah, a lot of our stuff had been imported previously and we’d had a couple of tracks on some compilations, but yeah, I think Hello Cruel World – a composite of our first four EPs – was probably the first thing that was domestically available in the States.

I guess a lot of that was through Gerard Cosloy?

Who we stayed with when I went over there, which was interesting because at that point, he was the bass player for GG Allin.

Did Tall Dwarfs go overseas before your solo tour with The Clean?

No, I went over solo the first time in ’89 with The Clean. Then Tall Dwarfs went the next year, from memory. 1990 I think. I stayed with Gerard on the ’89 tour in New York.

Alec Bathgate and Chris Knox.

How was it staying with him?

It was great. He had a lovely girlfriend – whose name escapes me – she was really nice. He was very dry and fun. Fun in a funny sort of way. Her brother was living downstairs in their basement, and he seemed like he could be serial killer material. It was all very New York; it was all very thrilling. Everything about New York was thrilling back then, until Giuliani fucked it up.

“Everywhere we went, people were going, ‘I’ve been waiting years to see you guys.’”

What are your other memories of that tour with The Clean?

Going into New York at 10 o’clock in the evening in a big black stretched limo driven by a big black stretched man and seeing the steam coming up from vents in the street. It was just like, “Oh yeah! We’re in Taxi Driver – woo hoo!” The gigs went down really well. We were amazed how well we were recognised, because that was the first time The Clean had been over as well. Just everywhere we went, people were going, “I’ve been waiting years to see you guys.” “You have?” Shit a brick. And they’d have all the Flying Nun original 12"s and getting us to sign them and all that sort of rubbish. It was an eye-opener, I tell ya.

Do you think you surprised them by being quite Kiwi?

Yeah, especially with my stuff. A lot of them thought I’d be really serious and quite dour like some of the lyrics. I think they got quite a shock to see that. One, I couldn’t play properly. And two, it was rickety as hell and I was dressed funny with jandals and shorts and so forth. I’d bleached my hair blonde at that point too. Just this pathetic idiot onstage, fucking up songs and getting people onstage and being a clown. That took a lot of them a bit of getting used to. Some of them were mortally offended by the fact that I didn’t take the song that had changed their lives completely seriously. Likewise with The Clean, but in a slightly more diluted form because they could actually play.

The Kilgours were a bit … cooler too, I guess?

Yeah, but nothing cool about Bob [Scott]. They did have that going for them as well.

What was your role at Flying Nun through the 80s? I heard you did distribution early on.

Yeah, Barbara [Ward] and Doug [Hood] and Carol [Tippet] and I would carry records around to the various shops. It was very very low key, but it worked a treat. They bought heaps. What’s forgotten too, is that the second-hand stores in Auckland at the time were selling New Zealand stuff at cost. It was fantastic. Real Groovy, Revival, and the Record Exchange all just sold them for what they bought them at, as a way to help New Zealand music along. I think a lot of people have forgotten that, but they shouldn’t because it was a fantastic gesture on those people’s parts, and it worked a treat.

Then there were people like the ex-head of the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand, Mark Ashworth, who at the time over on the shore was buying up all the New Zealand stuff and selling tapes of it for a dollar each. Or maybe you could hire them off him and tape them yourself? Whatever it was, it was so diametrically opposed to what he ended up with at RIANZ, but that’s neither here nor there.

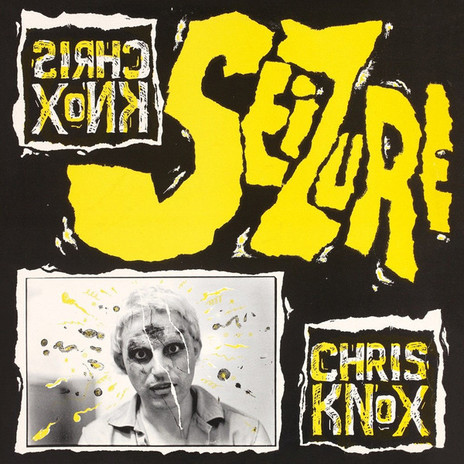

Chris Knox - Seizure (Flying Nun, 1989)

For that first overseas tour, I heard the European leg was all done in a station wagon.

Yeah. In fact, that first tour, our driver was Phil Morrison, who’s now a feature film director. He did the film Junebug just a wee while ago. So we’ve got a connection with someone who became more famous than us! It was very low rent, low key.

He did all the driving?

For that first tour, yeah, I think so.

Was that an impetus for your solo career kicking off more seriously? You’d already been playing solo a bit through the 80s.

A little bit. I’d often play Toy Love and Tall Dwarfs songs to keep things together because I only had about eight songs of my own, because most of the stuff from Guppies was not playable live really. But yeah, just before going overseas, Seizure had been released and ‘Not Given Lightly’ had been a very minor hit. It didn’t sell a hell of a lot, but it got into people’s psyches, and it was very easy to do live.

--

Coming up in part three: Chris Knox discusses his increasing musical output from 1990 onward and the time Green Day supported the Tall Dwarfs.