Introduction

In 1979 Terence Hogan was an Auckland-based writer and graphic artist involved in comics and music. He contributed to the comics periodical Strips, and designed two of the best-known record covers of the period: the AK79 compilation album, and the picture sleeve of Toy Love’s debut single ‘Rebel’ b/w ‘Squeeze’.

By day, he worked in promotions for WEA (NZ) Ltd, the local branch of the US multinational whose cash-cow was the soft-rock coming out of California. He managed to persuade his employer, WEA’s Tim Murdoch, to sign Toy Love, who had quickly made a nationwide reputation for iconoclastic live shows and biting songs that fused punk with pop.

Hogan became closely involved with Toy Love, and in 1980 after the band signed with Australian independent Deluxe – owned by Michael Browning, who managed AC/DC in its early years – it was suggested that Hogan accompany them to Sydney as a “personal manager” (alongside Doug Hood, whom he regarded as their true “street manager”). He would be paid a small retainer for his work, which involved promotion and acting as a conduit between the band and record label. That suited Hogan, for whom the band was never less than a passion. He writes, “I knew that for me the Toy Love-shaped hole left by their going to Australia would not be filled.”

The idea was that Toy Love would record an album while living in Sydney for a few months, then head to the UK, says Hogan. “The prospect of hitting London with an album and a few months’ worth of new songs in the bag not only fuelled the band’s eagerness to go ahead with this, it was the whole point.”

In January 2019, 40 years after Toy Love began its incendiary 20-month burst on the New Zealand music scene, Hogan published an epic account of his time with the band. A compelling read, Hogan’s Toy Love memoir is reflective, sober, and funny. It also works as a social history of Auckland music in the late 70s. But most often it is poignant, devoid of hype, and full of love for the band and its members: Alec Bathgate, Mike Dooley, Paul Kean, Chris Knox and Jane Walker.

In its entirety, Hogan’s memoir celebrates all that was exciting about Toy Love: their dramatic performances, their confronting, melodic songs, their achievements as New Zealand’s leading band of the post-punk period. AudioCulture is honoured to publish two excerpts from Hogan’s memoir, and has chosen passages that explain the difficulties encountered once the band left these shores. Below is an account of their frustrating, enervating time in Australia; a link leads to a description of how their only album was recorded in Sydney, to mixed response. These aspects of Toy Love’s career have always puzzled their fans back in New Zealand. The story begins with Hogan heading to Auckland airport with the band. The complete memoir can be read at Hogan’s website. – AudioCulture

--

Toy Love in Australia

I sold my Ford Consul to a local drummer, and took in some of the cheerful chaos of Toy Love’s farewell at the Windsor in Parnell on the Saturday afternoon, where the door money ended up on the bar. The next day I joined the band, Doug Hood, roadies Ian Dalziel and Chris Moody, Barbara Ward, Georgina Trayhorne and Carol Tippet (partners of Chris Knox, Alec and Doug respectively) and hopped on a flight to Sydney.

The band house in Sydney was at 82 Windsor Street, Paddington, just a few doors away from a corner pub called the Windsor Castle! The two-storeyed terrace was roomy enough in itself, but didn’t feel very commodious with a dozen of us living there. I ended up sharing a room with Chris and Barbara, which was unsatisfactory for all concerned. Fortunately, I could afford to pay a little rent and I urgently set about finding somewhere else to unroll my swag. I soon holed up in a small garret-like space a couple of floors above a band practice room off the bottom of Oxford Street, which would do for the duration.

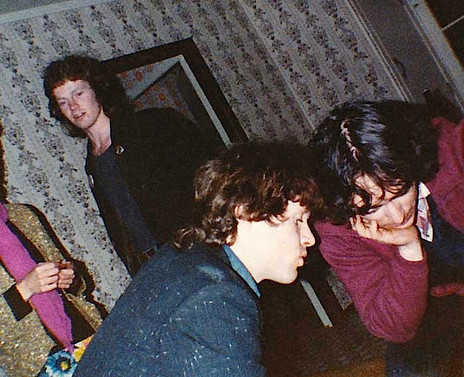

From left, Jane Walker, Mike Dooley, Chris Moody, and Doug Hood mooching around at Windsor St. - Carol Tippet

The practice room would later be used for the video of ‘Sheep’ on the Toy Love DVD. The other occupant was a seasoned Scottish roadie and sound man who knew the Sydney music scene. He worked with Toy Love regularly and it all appeared to go reasonably well, despite his insistence on playing the same Rose Tattoo track for every soundcheck, as Alec recalls. But the relationship ended badly when he seized Mike’s drum kit in lieu of money he believed he was owed when the band left Sydney. Mike had bought the kit from Jamie Jetson of The Idle Idols, and hadn’t finished paying for it. When he eventually returned to Sydney and left money with someone to be passed along to Jamie, the cash never reached her. Unsurprisingly, drugs were involved.

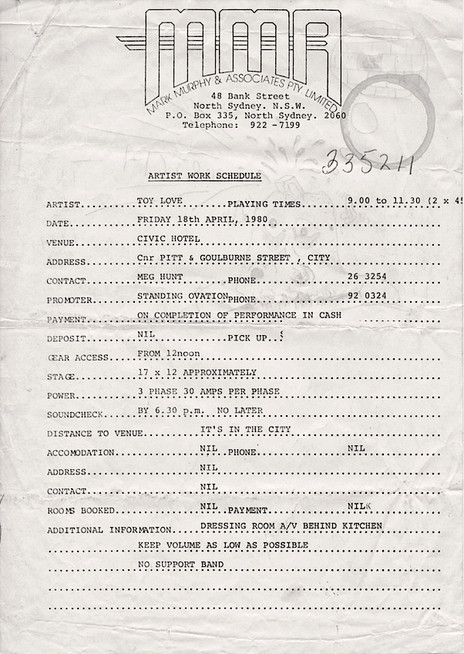

Michael Browning’s Deluxe Records label was housed in an office block in Bank Street, North Sydney, along with Mark Murphy and Associates who handled the bookings. This required us to regularly make the trek across the Harbour Bridge for meetings and pep talks. A trip made with some enthusiasm at first, but less so and in dwindling numbers as time went on.

Toy Love signing with WEA Records (NZ) and Deluxe (Australia), 1979: Alec Bathgate, Jane Walker, WEA's Tim Murdoch, Deluxe's Michael Browning, Paul Kean, Mike Dooley, WEA's Terence Hogan and Chris Knox - Chris Knox collection

Doug set to work tracking down one of the old red Post Office vans which were popular among the city’s bands, and found one that would have struggled to pass any vaguely diligent roadworthy test. Shortly afterwards, the van was found outside the band house one morning sitting up on bricks nicked from a nearby wall, with all four wheels missing. It was soon replaced by a similar van that managed to retain its wheels, which was useful.

Toy Love played their first Australian date on Tuesday, 11 March 1980, two days after arriving, at the Civic Hotel on the corner of Pitt and Goulburn Streets. They supported another Deluxe band, The Numbers, and the turn-out was good with plenty of expats and lots of enthusiasm in general. Chris came off the stage feeling confident, he’d enjoyed this first hit-out, and despite all the recent disruption and hassle I remember feeling similarly positive and looking forward to whatever Sydney had in store.

Booking sheet for the Civic, Friday, April 18th. Additional Information includes “Keep volume as low as possible” and “No support band”, although Alec records that Auckland band Proud Scum played too. - Chris Knox collection

The Civic Hotel, Sydney, where Toy Love had a residency of sorts.

The band hit the ground running and within one month had played 29 gigs and wasn’t slowing down. It only took a couple of weeks for Toy Love to be banned from two Sydney venues: the Sylvania Tavern (a suburban barn where a tiny crowd turned up) and Maroubra Seals RSL. Exactly what was done or said that put people’s noses out of joint is not clear to me to this day. There was mention of some swearing and a transgressive trouser episode that I must have missed. I’m more inclined to think that the good folk running these places just didn’t like Toy Love, their sound, their look, their audience, and didn’t want to deal with this stuff. Too strange and abrasive, and not nearly enough drinkers at the bar.

At a band meeting with Deluxe and the booking agents Michael said that he and the agency had talked over this business of being banned, and what sort of venues should be targeted in future. This was early on, so the room was fairly full. Someone from the agency mentioned a “so bad they’re good, kind of thing” as maybe a way to promote the band. There were some raised eyebrows and sidelong glances at this statement. Nobody said anything, and I had a slightly sinking feeling. In trying to build a following in this huge city which was already showing signs of resistance, were we relying on people who seemed to fundamentally misunderstand Toy Love, and had maybe already lost confidence in their decision? I knew it was too soon to be so negative but the thought did cross my mind. However, we never heard the “so bad they’re good” proposal again.

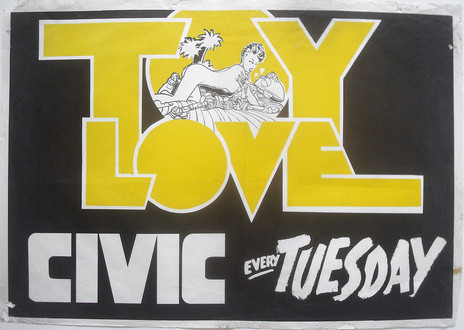

Poster for gigs at the Civic Hotel, Sydney. - Chris Knox collection

The Civic soon became a valuable semi-residency on Tuesdays and Fridays, while other regular venues included Chequers, Metropole, Stagedoor and the Astra in Bondi. I thought the Civic and a couple of the other inner city venues were okay, but there were far too many pointless gigs to pitiful crowds way out in the burbs. At some places the uninvolved patrons would just sit it out while the band played, and then get up for a bit of a dance when the disco started.

Typical of the attitude of some venues to Toy Love was the incident in a Blacktown club, described in John Dix’s book Stranded In Paradise, where the band were advised over the PA to not give up their day jobs. A pattern was established during these first few weeks. There’d be four or five gigs in a row that were often very sparsely attended and low on atmosphere and enthusiasm, and then there’d be a great night with a feverish crowd in a packed room. But the next few gigs would again be lukewarm at best, and it was difficult to feel that things really were building.

My friend Christine was by this stage living in Sydney, along with some Christchurch buddies who’d succumbed to their wanderlust and ended up in the Australian city where their favourite band was playing. She remembers Toy Love gigs where her little group made up a large portion of the crowd. One night I was walking down the steps from the street into a club where the clamour around the entrance looked promising, and a bunch of punkish kids pushed past me on their way to the door – one of them shouting “C’mon, don’t wanna miss Toy Love!”. The fact that I remember it well reflects how such a tiny moment can be a boost among the discouraging near-empty rooms that were so common at the beginning.

While visiting Sydney, WEA boss Tim Murdoch chose a club in William Street to check out the band for the only time during their stay in Australia. On the night there were just a handful of people milling around and Tim and I were up on a mezzanine looking down at the stage, where Toy Love were belting out a set for this meagre turnout as if the place was full to the rafters. I told Tim about a gig in another inner city room a couple of nights before that had been one of those very good ones, with both the band and a packed crowd in raging form. I don’t think he was convinced and he didn’t hang around for long.

Of course, it wasn’t all grim. Good times were had, birthdays celebrated, plenty of laughs and funny stuff … and those nights when the familiar Toy Love power and humour brought the room to life, thrusting all those great songs at an audience which was very much in the mood. Nights which approached the experience of playing to an eager crowd back home. I noticed a few familiar faces reappearing and one or two characters who seemed to be at almost every inner-city gig. Some people were getting it. Still, the number of sparsely filled rooms suggested that Sydney might have had only a certain level of acceptance for a band like Toy Love, and maybe that plateau had been reached fairly early on. It was a grind, and of course it was always going to be one. Bands doing it tough in a big new city is a rock’n’roll cliché, and Toy Love’s grind in Sydney fits right in there.

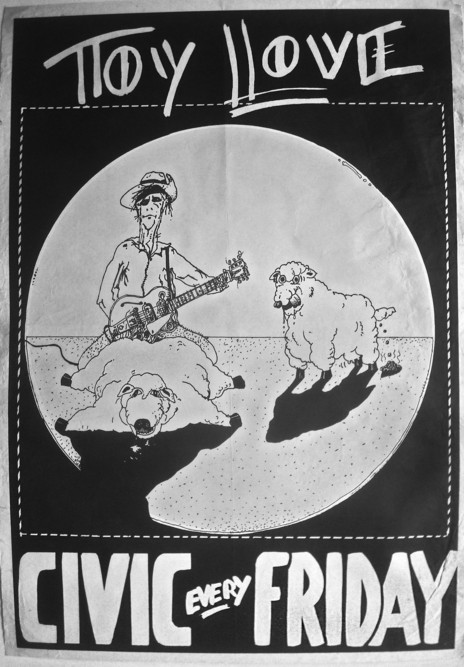

The agency called, there was a minor crisis. Doug, Ian and Chris Moody had been out on a poster run and, in their exuberance, plastered an otherwise pristine stone wall in the city with several of Alec’s “Civic every Friday” posters. The one with the guitar-playing digger in a slouch hat in sexual congress with a sheep while another sheep looks on, licking its lips. Now there had been a complaint and I assumed that, predictably, someone was offended and had made a fuss. “No,” said the caller, “they don’t have a problem with the poster itself. It’s just that the wall is private property and the posters have to come off, immediately”. There were no other posters pasted up there because the local bands knew it was off limits. So we all jumped in the van, raced down to the wall in question and started scratching them off. This scabrous poster did upset some people, but not to the point of anyone insisting something should be done about it.

Alec Bathgate's infamous “digger” poster.

At times the band’s – and particularly Chris’s – penchant for rubbishing Australia one way or another on stage and in interviews, has been cited as contributing to their problems in Sydney. I’ve never thought this was true in regards to promotion – if anything, the media loves spiky personalities and controversy. It’s also fair to say that Chris rubbished New Zealand in many respects just as consistently as he ever knocked Australia. In one interview he says that New Zealand and Australia both stink. He also said that they wanted to get to London, “which also stinks, only maybe it’s a nicer stink”. When in the mood, Chris could be an equal opportunity insulter with a pointed sense of humour and things were no different in Sydney. While there, I never met an Australian who seemed bothered by it.

Another band on Deluxe was the yet-to-be colossal INXS. We occasionally double-billed with them at places like Chequers and Stagedoor, and I particularly recall a daytime gig at Sydney University. They were a friendly lot who made a point of sticking their heads in the band room door to wish everyone good luck, and Michael Hutchence in particular would always watch Toy Love from the back of the room. Hutchence’s sinuous stage presence already had an obvious allure for many in their audience, and as a group they glowed with ambition. However, although I hardly saw any bands in Sydney that appealed to me, I just never thought that INXS were among the city’s most likely to go humungous – which shows what I know.

I did get to see a few Australian bands, mostly those on the same bill with Toy Love. I liked some more than others, but generally nobody jumped out at me in a way that made me want to seek them out on nights off. Bands with real personality and originality seemed to be thin on the ground, and that typical sound – with the bass guitar and kick-drum cranked right up and the other bits smeared over the top – was everywhere and horrible.

The Toy Love tin foil period at its height. - Carol Tippet

Deluxe released the first two singles as a four-track EP, distributed by RCA, with a cover featuring a Philip Peacocke photo taken in Auckland of the band messing about with some car doors. I know the record got some airplay on Sydney radio, particularly on 2JJ who had also played the first single, although I don’t recall hearing it other than during an interview that Chris and Jane did for 2JJ’s New Noise program with Pam Swain. I’ve still got the interview on a C90 cassette:

Pam Swain: Why did you come to Australia? “We just started making stacks of money in New Zealand so we came here and started losing stacks of money.”

Pam Swain: If you hadn’t left New Zealand, what would you be doing now? “Probably starting to get totally unpopular in New Zealand and thinking seriously about killing ourselves or getting jobs and going to England.”

When asked about whether he’d always been a writer, Chris says that he’d been writing songs at the piano since he was 14, “horrible wimpy things … but they always had nasty lyrics”. Talking about the records the band had made so far, he regrets their inexperience as a group in the recording studio, and the consequences. The second single especially, being recorded and mixed too quickly, while the guitar levels on ‘Sheep’ just don’t do it justice. Chris and Jane stress how different they sound live and mention that the booking agency in Sydney had to completely reassess their approach once they’d actually seen the band play. The interview was done 10 weeks into the Sydney period and among the quite reasonable questions and slightly strained humour, a certain frustration shows through.

I never once got up on stage with the band while they were playing, but there was that time at the Astra in Bondi. There was nobody on the dance floor in front of the stage where I was standing, unusually so because I preferred listening from the back of the room. As the chorus for ‘Sheep’ came around Chris suddenly jumped towards me with, I’m sure, a mischievous grin and stuck the microphone in my face. I took the hint and joined in the “I don’t know where I’m going to” refrain. For some reason I hung onto the mic and belted out the final verse and chorus with some relish, I must admit, and the band went right along with it. Back at the mixing desk a guy from the agency came up to me and said, “That was great mate. Bit of a surprise … didn’t know you were creative”. A couple of nights later at a different venue, Chris beckoned me over at about the same point in the song, but I waved him off. It was fun to do once, but I wasn’t interested in a regular spot.

French’s Tavern at 86 Oxford Street was another storied venue, with sticky carpets that had felt the tread of early Radio Birdman, The Birthday Party, and Hound Dog Taylor among many others, as well as a host of unsung outfits like Lubricated Goat and Real Fucking Idiots.

French's Tavern, Oxford Street, Sydney, 1970s.

Despite really disliking the place, downstairs at French’s is one of the very few Sydney rooms I have a clear picture of because Toy Love played there nine times. Always on Monday nights, and typically to a mix of gaunt and distracted Darlinghurst locals with a handful of cider drinkers and curious rock kids. For Toy Love, a double bill with Auckland band Proud Scum when they were in town was a highlight of those gigs.

Also popping in one night was journalist Clinton Walker, who must have seen the band photo with the suits taken at the ‘Squeeze’ video shoot. He was disappointed that they didn’t look as sharp as he was expecting when he went to review them for Tagg magazine, and calls them slobs. Whatever the deficiencies of the late set that he saw, his summing up of Toy Love as “following a formula” and “yet another bland pop band with little to say and less style”, suggests a determination to be unimpressed. Toy Love, bland? Mind you, Stuart Coupe had called them “energetic and tedious”, so there seemed to be a consensus among certain critics, puzzling as it is. Shane Nichols in Australian Rolling Stone was much more positive, saying that the music might at first seem abrasive and convoluted, but “a little exposure leads to a better appreciation of the richness behind that hard exterior”.

Hanging out at French’s on a Monday night wasn’t among my favourite things to do in Sydney, so I can sympathise with Walker on that level. While doing a little fact-checking on the venue I came across a post by Brian Wakefield who’d played upstairs there with the Layabouts around the same time. He notes that “after two years of stepping over mandied-out bodies sprawled on a stinking soggy carpet to get to the stage, we’d had enough”.

Still from an interview filmed at Windsor St., July 1980, and shown in NZ the following month.

So, you get the flavour. I was usually glad at the end of the night to go into the back office, pick up the $125 in cash and head home. Or maybe to that bare, nondescript bar upstairs in a Kings Cross backstreet, where we sometimes killed an hour or so with snooker and beers, before calling it quits. Now, what was that place called?

There’s a comment on YouTube, under one of the videos of Toy Love playing live in 1980, where somebody brags about seeing the band “at their peak before softening to appease the music companies and venues”. I don’t know when this softening and appeasement were supposed to have occurred, but it’s a claim I’ve seen elsewhere. There were venues where they might have been more interactive and unrestrained than at others, but that was the case throughout the band’s lifespan. And to be blunt, the bloodletting just wasn’t sustainable long-term. But they never lost their intensity or moderated how or what they played to appease anybody, despite having the plug pulled on them often enough by grumpy proprietors. Every decision they made, they made for their own reasons and on their own terms, and I don’t think anyone who saw them during the final New Zealand tour would feel that any softening was apparent. This doesn’t mean that as the “record company guy” I didn’t get the occasional word of advice or caution from well-meaning souls, which I ignored. Toy Love would have been a great band if I’d never seen or met them, and they didn’t need me to tell them how to go about things.

One little incident relevant to this does spring to mind. I would go over to the Deluxe office in North Sydney some weeks to hand over the money from the couple of venues that paid in cash and, early on, pick up the band’s pocket money. This might amount to $50 split amongst the band for a couple of weeks; so it started out pathetic and quickly dwindled to nothing. On one visit I was talking with Michael and someone else from the booking agency. By this time it was clear that both the label and agency were getting concerned about the slow uptake for the band in Sydney and, I assume, the sluggish income. I don’t think Michael himself was unduly worried about this and was prepared to be patient, but someone had been getting into his ear about where the “problem” might lie.

Toy Love: Paul Kean, Mike Dooley (rear), Jane Walker (front), Chris Knox and Alec Bathgate. - Philip Peacocke

Some people thought the band was hard to dance to, and that maybe a different drummer was an idea worth looking at. That was the gist of it. I sensed that Michael was choosing his words carefully in passing this idea along. So, also choosing my words carefully, I said that not only was that not a problem, but Mike’s drumming was crucial to Toy Love and in my opinion any pressure along those lines would not go down well. Michael asked if I thought it was worth him sounding out Chris about this idea. I said that it was, only because I could give an opinion which I believed reflected the band’s view, but maybe Chris should confirm that one way or the other. So I agreed to return to Deluxe with Chris later in the week, and although Michael preferred that Chris didn’t know what the meeting was about, I said it probably wouldn’t go like that.

A couple of days later on the way back over the bridge, I told Chris what had been said, the comments about Mike’s drumming, and what my response had been. I don’t clearly recall his reply, there might’ve been a “Huh!” Oddly enough, at the meeting nothing at all was said about Mike, the drumming, the line-up or anything else so related. I kept waiting for the subject to come up while various other things were discussed, but there was no hint of it that day or at any time afterwards. I did tell Michael that I’d mentioned the subject to Chris beforehand, but didn’t press him on why he’d dropped it altogether. My guess is that he knew that whatever the “problem” was, it wasn’t Mike.

Painted TV set, a spot, a black-light, and fluoro daubed bits and pieces on the backdrop. No expense spared. - Michael Green

Sydney living was hard on the pocket, despite every effort to do all the daily things on the cheap. I soon found that paying my rent, getting around the city as much as I needed to (there was a lot of walking), and keeping myself passably fed and watered, pretty much shredded my modest WEA retainer. My lasting gratitude goes to those friends whose occasional invitations to a meal would bring relief from toasted sandwiches on the run or yet another complimentary late-night curried rice in some crummy bar. I reminded myself that it was all a temporary situation, the life experience was surely worth it, and that the band was doing it at least as tough in Windsor St. Their situation was only made tolerable by a couple of their partners having found work in Sydney, which helped everyone keep body and soul together. As a “bonus”, where venues provided cheap meals as part of their liquor licence obligations, the band could sometimes indulge themselves at the trough of mince remaining unsold at night’s end.

I arrived at the band house one morning to the news that Chris had badly gashed his hand in an overnight altercation with a bedroom mirror: a Toy Love kind of episode. When I got to St Vincent’s Hospital and met up with Doug, there was some concern about what to do. Chris was actually in fine fettle and keen to make it to the gig at the Civic, and although the staff was set against the idea we were sure they could be brought round. I went to speak to the doctor who seemed to be in charge. He really didn’t want Chris to aggravate his injury by working that night. Trying to look as sensible and trustworthy as possible I told him that Chris was adamant he could do it, the gig was very important to us and that I would take personal responsibility for him … whatever the hell that meant. Maybe he could be bandaged in a way that would allow him to at least stand on stage, hold a microphone and perform with a minimum of risk to his hand.

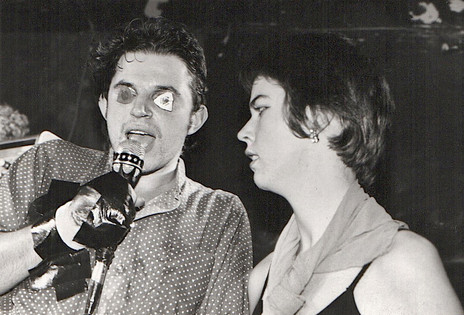

Chris Knox, all pick-eyed and bleeding subsequent to the mirror incident. Jane Walker looking concerned. Toy Love, Sydney. - Carol Tippet

Realising that Chris was going to perform despite his advice, the doctor consented. I’m not sure where the on-stage photo of Chris with his hand gaffer-taped to his chest was taken – it might be the Civic, although the bandage sure doesn’t look like a hospital job. There’s another shot of him at the EMI’s studio 301 which is testament to the care taken at some stage in swaddling his arm in a humungous bandage, to protect it when recording began for the Toy Love album the following week. A major ambition for all of them was finally being realised. [Read: Toy Love Make Toy Love, about recording the album.]

Chris Knox at EMI studio with bandaged arm. - Carol Tippet

On Saturday, June 28th, a lip-synched ‘Squeeze’ was filmed for TV’s Countdown music show, to be shown on the Sunday. Other bands that night included The Angels, INXS and Sherbs – and host Molly Meldrum came over to exchange pleasantries to Jane and I as we loitered by the stage. The highlight for me was Chris taking some change out of his pocket and handing it to the kids at the front of the crowd, thanking them for their enthusiasm.

‘Squeeze’ was repeated on Countdown a week later, but I don’t recall any mention of a spike in record sales, general interest or anything else following these broadcasts. Some people questioned the wisdom of doing a show like Countdown at all, as if there was a precious Toy Love image that needed to be protected. An image that might be blemished by appearing on a show that most people I knew who were in a band of any sort, watched anyway.

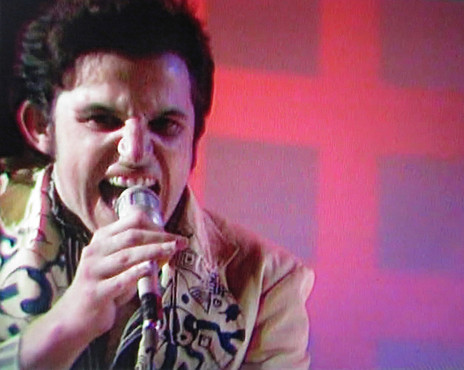

Chris Knox wearing Terence Hogan's jacket on Countdown.

Being Toy Love on tape or vinyl, TV, film, video, as real life or a cartoon … it was all out on the table, there was nothing to protect. Having said that, it is a peculiar moment. They are introduced by Daryl Braithwaite of Sherbert, who is clearly surprised that this outfit he’s never heard of should be mentioned in the same breath as Split Enz. The band has a rather removed attitude that leaves all the focus on Chris, who works the camera, venting about guilt, shame and self delusion. The Toy Love persona resists the showbiz ambience of Countdown to a degree, but doesn’t overcome it – three and a half minutes amongst the glitz and the warm pink glow, and they’re gone. I have no idea how it came across to anyone who’d never seen or heard them before.

Doug and I watched the All Blacks lose at the Sydney Cricket Ground before Toy Love left town for Melbourne the following day, playing the Prospect Hill Hotel on 15 July. By then I was back in New Zealand. Michael Browning had asked if I would help Auckland booking agency New Music Management set up a New Zealand tour that was due to begin at the Windsor on August 5, and start promotional work for the album.

Toy Love played five gigs in Melbourne before returning to Sydney for about a fortnight, then flew back to Auckland in the first week of August. Meanwhile I was back at WEA, having slotted into the role I’d left behind four months previously, as well as working on promoting the Toy Love album and liaising with NMM about the tour. It was good to be back in a familiar environment and I recall feeling upbeat and looking forward to the national tour, as I’d hardly travelled at all with the band in New Zealand. At the same time, I’d heard interesting things about Melbourne, including from Michael Browning who regarded it highly as a music town. I was curious about the place and regretted not being there with the band.

In the end, Melbourne remained probably the biggest “what if?” in the whole Toy Love in Australia story. Talking to the band in Auckland on their return, it was clear that Melbourne was much more receptive than Sydney, and audiences like those at St Kilda’s Crystal Ballroom – where they received their only Australian encore – had seemed to immediately grasp what they were about. Alec has suggested that they “would have had a completely different Australian experience” if they had been based in Melbourne. There’s no way of knowing how different things might have been, but it’s a speculation that was reinforced by my own experience. By mid-1981 I was living in Melbourne myself and the scene around the Crystal Ballroom, the Prince of Wales and the small clubs in Collingwood and the inner north, struck me as being a natural habitat for Toy Love in a way that Sydney seldom, if ever, did.

Toy Love's final gig in Australia. The band flew back to New Zealand the next day. Poster by Chris Knox. - Chris Knox collection

One summing up of Toy Love’s demise that I’ve read is that they went to break Australia, but Australia broke them. It has a nice symmetry but it’s far too simplistic. In the paragraph about Toy Love in his book, Michael Browning admits that “Unfortunately, Australia just wasn’t ready for them” – and the band’s slow progress in Sydney was disappointing in contrast to the enthusiasm they’d generated at home over months of touring. Initially this wasn’t seen as a problem in itself, because Sydney had been regarded as a chance to work hard in a different environment, record an album, write a bunch of songs, and move on.

Doug might have felt vindicated in his misgivings about going to Australia in the first place; he later recalled looking for change on the floors of nightclubs to buy chips after gigs, or dealing with the shit attitude towards support bands on the Sydney circuit – “your PA is turned down, you got three mics and two lights” – and don’t bother complaining.

The idea of “breaking Australia” had never come up either within the band or with the record company. As Chris said in an interview with The South Tonight in early 1980, “We’re only going to Australia so we can go to England”. But I think there was a growing suspicion that a perceived lack of acceptance in Sydney could jeopardise the plan they had committed to as a group, and that Australia wasn’t a guaranteed stepping stone to the UK anymore.

Yet, despite the negative mood that had developed, in those few weeks there was probably more progress than many people realised, including ourselves. Later reports suggested that a genuine groundswell was there to be built on, and a return to Melbourne especially would’ve been an interesting proposition. But the truth is that no one in the band was interested in building on an Australian groundswell.

--

Read: Toy Love make Toy Love about the recording of their album in Sydney.

--

This article is an excerpt from A Toy Love Story, Terence Hogan’s memoir of his time with Toy Love. The complete story can be read at his website.