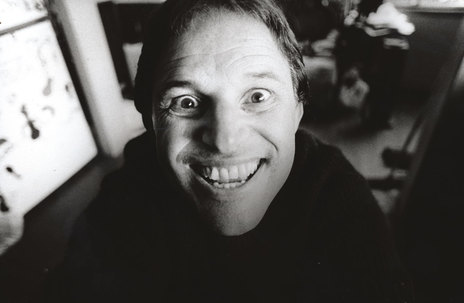

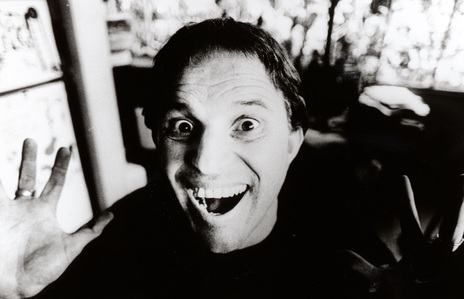

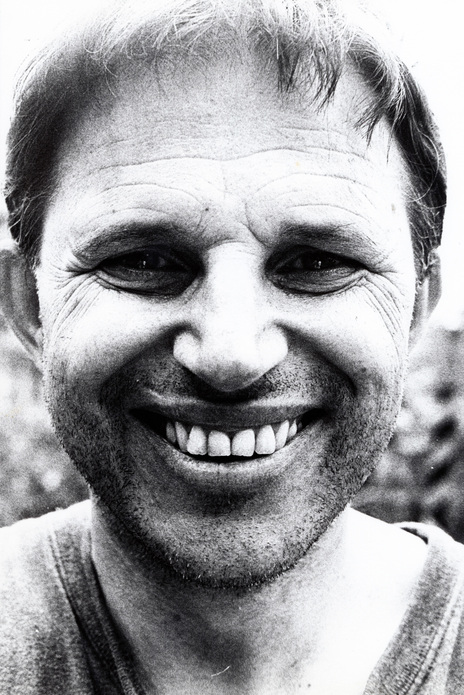

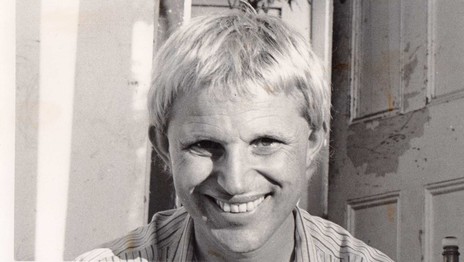

These days, Knox needs a caregiver, and hasn’t yet fully recovered the power of speech, but his face is still as expressive as ever. More so, actually, because he knows the face has to carry the signals.

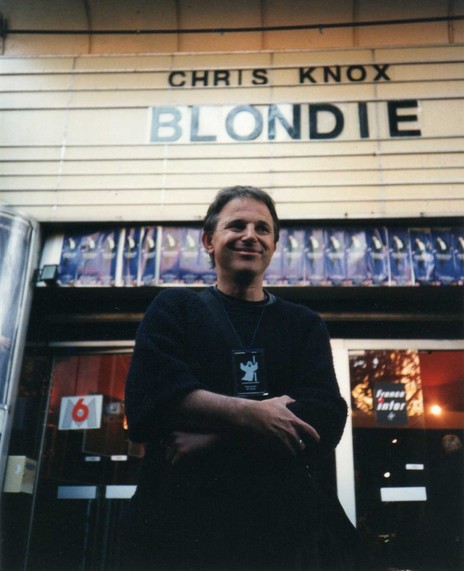

Yes, a radically changed Chris Knox greets the world, but he’s still here, even if he can’t get out there and sing, play, record, write, broadcast and animate like he used to. So this appreciation is no obituary, and it has warts in it, even if it’s not quite warts ‘n’ all, because Knox is the last person on earth who would ever want his idiosyncrasies smoothed over for public consumption.

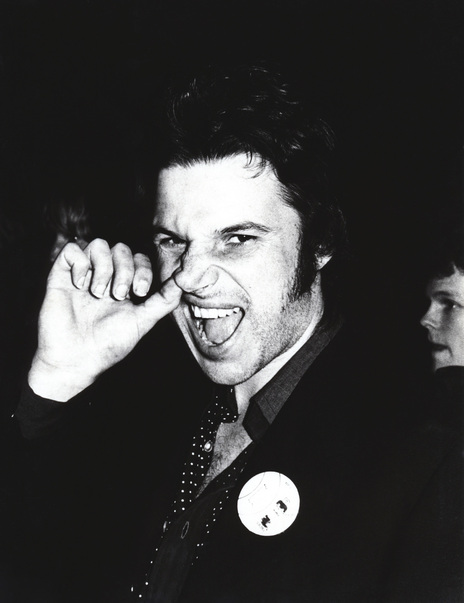

From that great revelation of punk rock on, he was the artwork, and he became a living embodiment of what he stood for.

Chris Knox, to paraphrase a line that Frank Zappa once said to me about his own music, is one heck of a thing to comprehend. He did so much, and his eclectic range of activities between his formative years in The Enemy through to his tragic stroke was so sustained that it’s hard to get your bearings. But there is one thing that runs right through the 32 years of his professional life: The unyielding, flinty integrity of Knox the man and everything he did.

In many ways, Knox was a typical New Zealand pragmatist, so from that great revelation of punk rock on, he was the artwork, and he became a living embodiment of what he stood for, a sometimes testy, often provocative advertisement for anti-pretension, another way of living, a new way of making music.

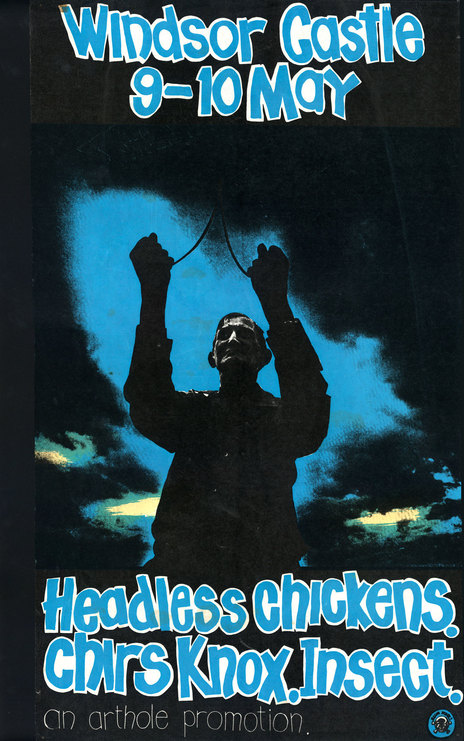

Punk Rock

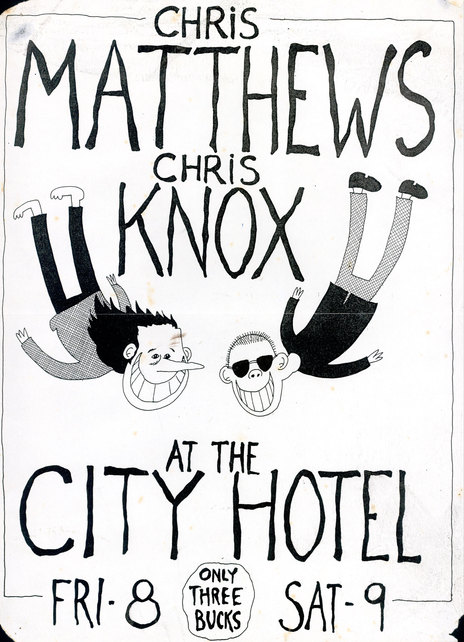

When punk rock exploded, Knox was already a good bit older than its target market, so he was able to absorb what it really stood for – do-it-yourself authenticity, not spiky hair and Dr Martens boots. The Enemy never made an album, but they influenced a generation of would-be punks, making Knox a punk godfather to the likes of schoolboy Shayne Carter, and dazzling former Enz man Phil Judd.

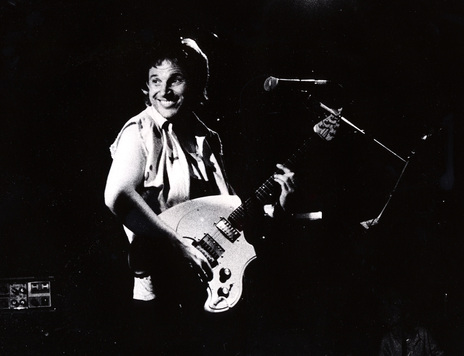

In 1977, Chris Knox was a self-harming Iggy Pop minus the abs and heroin habit, a dangerous, unpredictable Johnny Rotten without the stage management. And underneath the rock and roll rage, if you listened real hard, you could tune in to that hint of pure pop at its core.

And then, in 1978, came Toy Love, Knox’s second legendary band, and we’re not yet out of the decade of hippie festivals, enormous flares and the Donny & Marie Show. With Toy Love, Knox let his formative pop influences out of the bag. The group still had its punk mojo, but like The Swingers, the group Phil Judd formed when he realised he couldn’t get in on The Enemy’s action, Toy Love made razor-sharp, smart-funny, boisterous new wave pop that wowed audiences wherever it went.

The big studio experience proved frustrating, demoralising, depressing.

Except when it came time to make the big debut, financed by a multinational, the big studio experience proved frustrating, demoralising, depressing. This was a good thing, because if the group had accepted the status quo that they should just bend over and take it while the studio ‘professionals’ did the real work, then Knox may never have gotten angry and he may never have subsequently fomented a small revolution that would go on to change the world of music. Yes, really.

Home recording

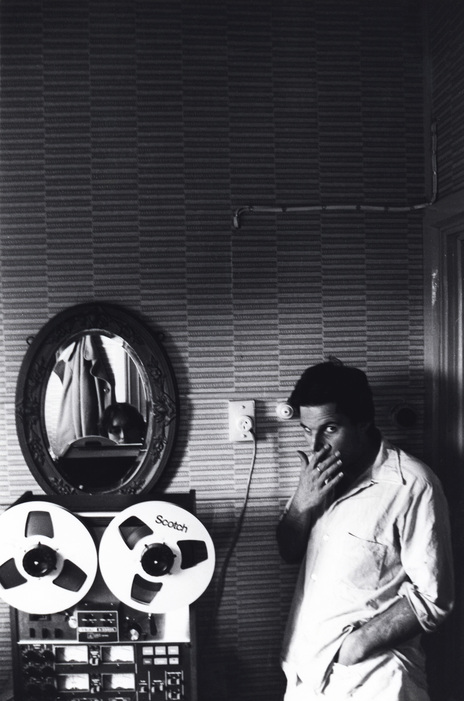

It’s hard to imagine in the 21st century, with every other musician working from their home studio, but in 1979 there was only one way to record an album: In the often oppressive environment of a "real" studio. It cost a bundle of cash, and an inexperienced group had to do everything the producer and engineer told them to do. It was an atrophied situation with the wrong hands holding all the power.

Knox – with the help of Doug Hood and a few others – changed all that, when he took a 4-track recorder down to the South Island to get their essence on the go. Roger Shepherd formed a record company around the results of those recordings, Flying Nun, and the rest is history.

Knox’s recordings of bands like The Stones, The Verlaines and The Clean revolutionised the local scene.

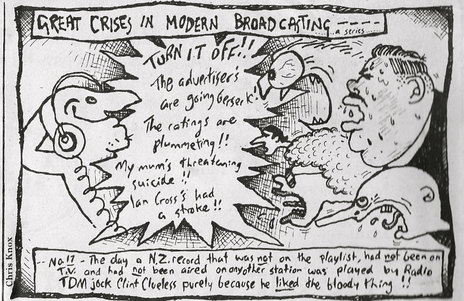

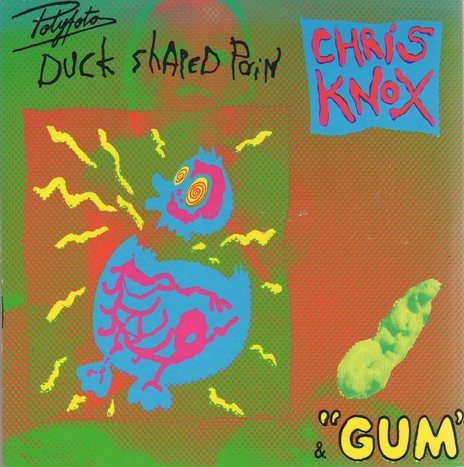

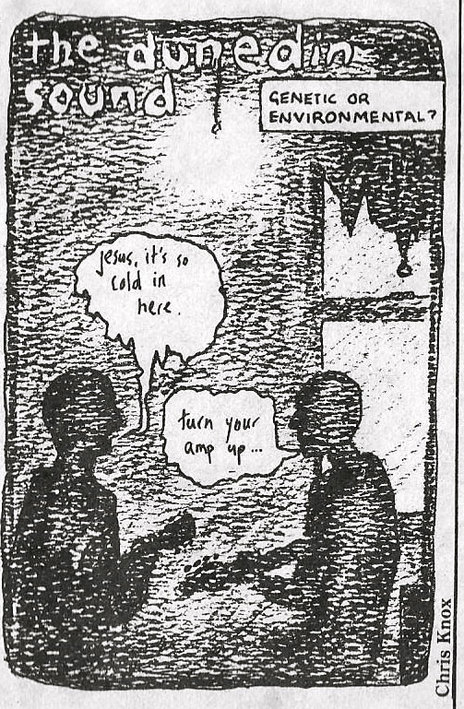

Rough as guts, sonically thin, but capturing the actual throes of real bands at chrysalis stage doing their thing in documentary fashion (or as Chris might have preferred, cinema vérité), Knox’s recordings of bands like The Stones, The Verlaines and The Clean revolutionised the local scene, and even though radio stations wouldn’t play them, they were popular as hell.

These records, and those he recorded with Alec Bathgate as the duo Tall Dwarfs, proved not only that there were bands and music of great quality down in NZ, but that rough-as-guts recordings could capture something the big, mainstream studios couldn’t. In time, this sound – later known as the lo-fi aesthetic – leeched out to Britain and America. In the former, groups like Flying Saucer Attack and Third Eye Foundation tuned in to the sonic degradation that resulted from off-the-cuff recordings, and in America a whole Knox-influenced scene began to revolve around groups like Smog, whose recordings were so degraded that the sonic character became a big part of what the band was projecting.

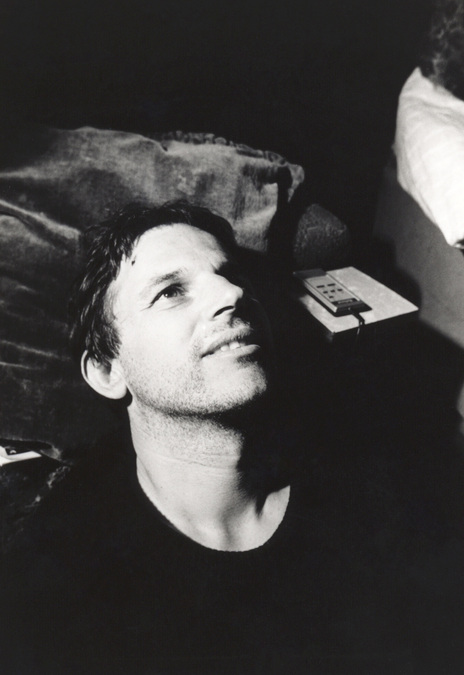

But here’s the thing: All this was happening without Knox’s participation. He had started the ball rolling. Meanwhile, he was busy at his new home in Grey Lynn, doing his own thing, flapping around – walking great distances - in his trade-marked jandals, starting a family, being a house husband, and being Chris Knox.

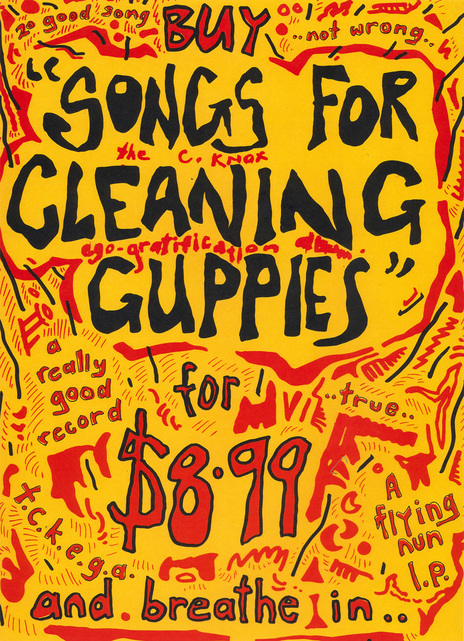

Chris Knox copped some flak for the so-called self-indulgence of solo albums like Songs For Cleaning Guppies (1983), and in 2003 for his Friend project (also known as Inaccuracies & Omissions). But so-called indulgence was part of Knox’s musical lineage: He had grown up loving The Beatles at their most indulgent, one of his all-time favourites being ‘Revolution Number 9’ from their self-titled double album (known as The White Album) from 1968. This epic track used collage and so-called musique concrete techniques created by 1950s composers like Pierre Schaeffer and Karlheinz Stockhausen, to spooky and compelling effect. In Knox’s language, who cares if it’s indulgent. As long as it’s not pretentious!

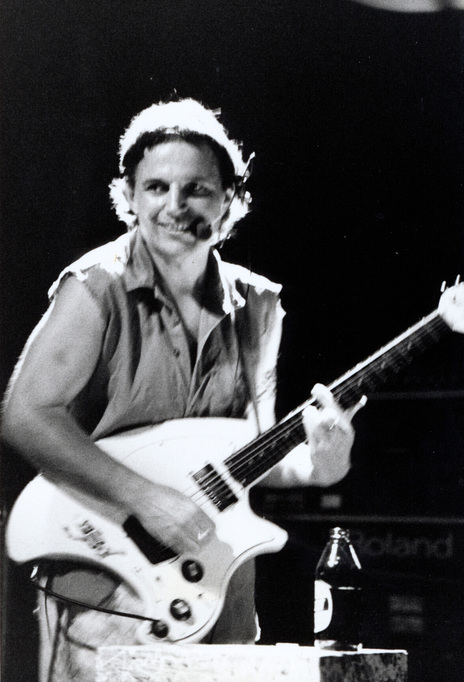

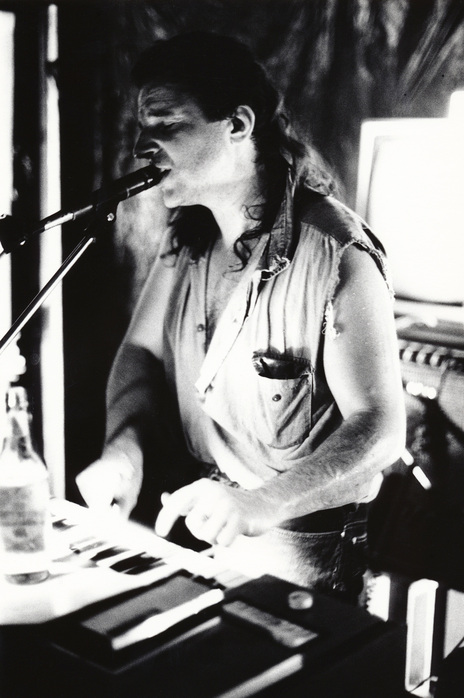

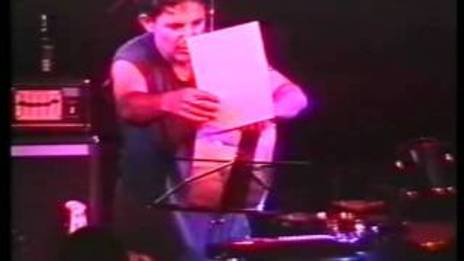

Knox was pretty landlocked during the 80s and the early 90s, and became such a regular fixture in Auckland that it was easy to take the guy for granted. It’s a problem in a small city. I used to joke about avoiding the Auckland University quadrangle, lest Chris Knox be yammering out yet another lunchtime set. Now, I wish I’d gone to more of them.

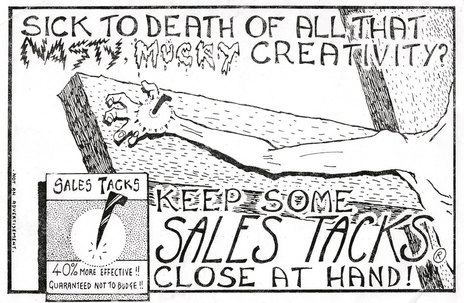

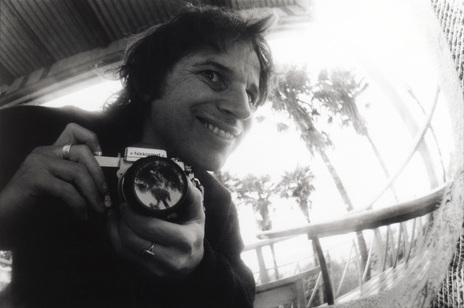

In reality, Chris Knox was a powerhouse of creativity and activity right through the 80s and 90s, always working away at a Tall Dwarfs or solo project, working on his comic art and brilliant stop-frame-animation video clips, appearing as a TV film reviewer and eventually arts show host. For a short while, he even reviewed albums in the pages of The Listener.

But aside from nourishing his own creative muse through which he fed his keen interest in horror movies (inspiration for Tall Dwarfs’ 1984 song ‘The Brain That Wouldn’t Die’), one of the less celebrated things about Chris Knox is his management of the Auckland end of the Flying Nun empire in the mid-1980s.

When I interviewed him in 1986, Knox was knee deep in a multiplicity of roles for Flying Nun, and worried about its future, because it had grown so fast, but obviously without the kind of administrative and financial base that a business would normally rely upon. For a while, it seemed that Flying Nun business had stopped Chris Knox The Artist in his tracks, but then a proper Auckland office was established in the city, with proper employees, and Chris was freed to do his own thing. That must have been a relief, even if it did create a demarcation line between artists and would-be alt-rock record execs.

In the 90s Knox spent a considerable period of time doing just that, careening about with a new generation that idolised him.

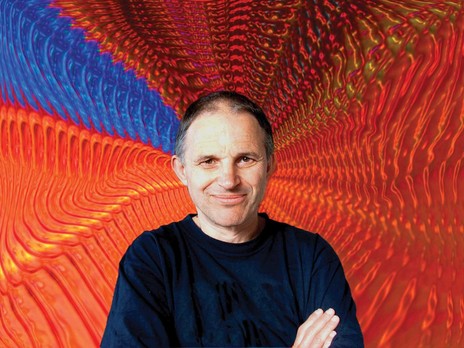

But just as well, because eventually those young Americans came calling, wanting him to tour the US of A, and in the 90s Knox spent a considerable period of time doing just that, careening about with a new generation that idolised him. That must have felt good.

In the same way that it must be galling for Phil Judd to get recognition for ‘Counting The Beat’ and little more, it must be galling for Chris Knox to be known as little more than the guy who wrote and sang ‘Not Given Lightly’ (No.13 on APRA’s list of Best New Zealand Songs Ever). It is, nevertheless, a remarkable song, and it shows what a remarkable vocalist he is.

But like I said way back at the beginning, it’s not just the quality of the work that makes Chris Knox special; it’s the fact that he applies the same integrity to everything he does. As a person, Chris has always been something of an agent provocateur, acting as a one-man bullshit detector. This stance can go badly wrong for those who don’t apply the same criteria to themselves as they do everyone else, but Knox always jandal-walked it as he talked it.

In 1997, I had dinner with Knox and violinist/filmmaker Tony Conrad, who had performed in an early version of the Velvet Underground, and the big-eyed sense of childlike fandom in Knox was palpable. That was cute. Later, Conrad screened one of his rare, controversial experimental films, Flicker, infamous for its strobing effects and carrying a warning about its potential to cause epileptic fits. Chris, who suffers from serious epilepsy, insisted on viewing the film, and I sat right behind him, worrying about what could happen. His insistence on subjecting himself to danger says something about the man. Not foolhardy, but determined to get out there and express his enthusiasm, to kick sand in the face of Mr Scared. Not Mr Risk-Averse. Not at all.

I’m hoping that maybe one of the mad scientists in the pop cult movies Chris loved so much will pop out of fiction and come up with a new way to rewire the brains of those who have suffered strokes, just so he can tell me what shit I wrote about him when he couldn’t talk for himself.