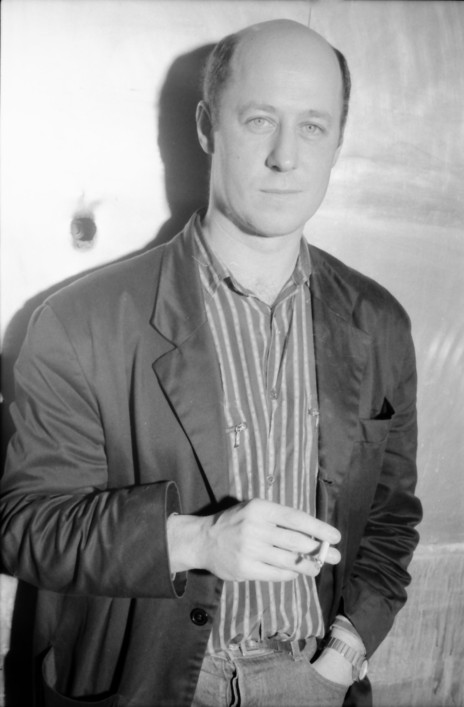

Simon Grigg

Since the mid 1970s there have been few areas of New Zealand popular music that haven’t felt the influence of Simon Grigg. At 21 years of age, he was managing an Auckland record store; soon he would also manage a pioneering punk band, then launch the first significant indie label since the early 1960s.

If playing a pivotal role in establishing Auckland dance clubs, and making ‘How Bizarre’ an international No.1 hit weren't achievements enough in the 80s and 90s, creating a online historical repository for New Zealand's popular music has ensured that the country's musical heritage will be remembered by generations.

Suburban Reptiles - Saturday Night Stay At Home (1978)

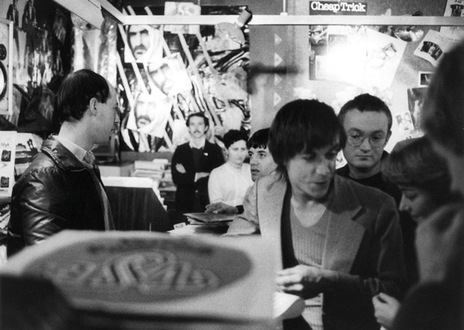

Simon Grigg, at right, ceremonially handing over the keys to the Parnell Taste Records store (the former Professor Longhair's) at 279 Parnell Road, to new manager Robert Nicholson in 1979

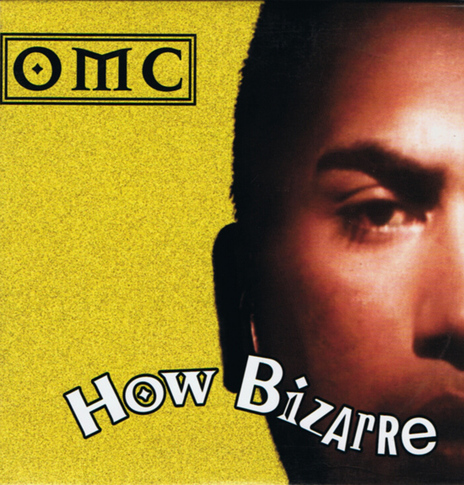

The 1995 cover for the 'How Bizarre' CD single.

Photo credit:

Conceived and directed by Alan Jansson and laid out by Gideon Keith.

OMC - How Bizarre (1996)

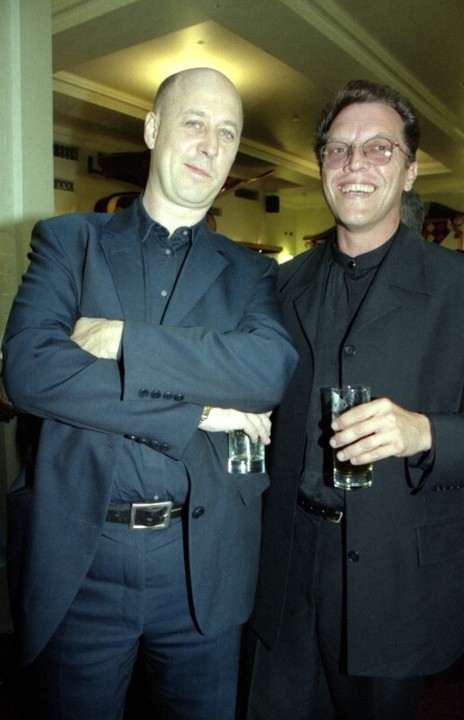

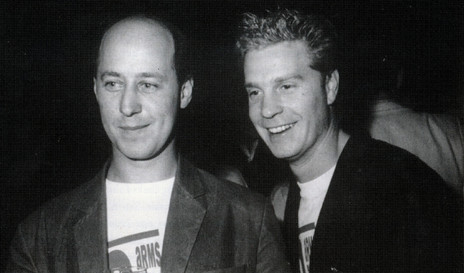

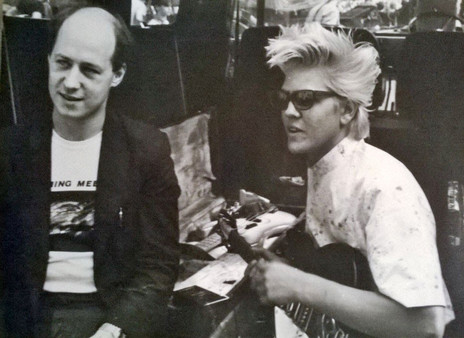

Simon Grigg and Rob Salmon, Beats Per Minute Show, BFM

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

Simon Grigg with Buster Stiggs (of Suburban Reptiles and Swingers fame), at the APRA Silver Scroll in 1998

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

Simon Grigg, Roger Shepherd and Doug Hood at the Apra Silver Scroll. Photograph taken at the Powerstation, Auckland, in the late 1980s by Murray Cammick

Photo credit:

Photo by Murray Cammick

The 1980 Roger Jarrett hand-inked design for the first Propeller logo

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

How Bizarre - The Story of an Otara Millionaire documentary (2014)

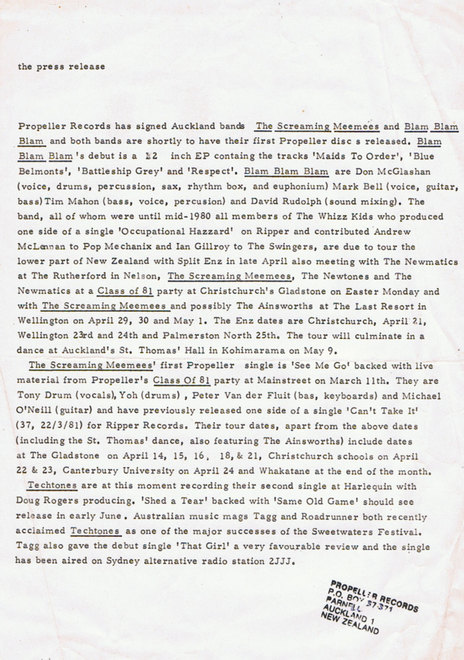

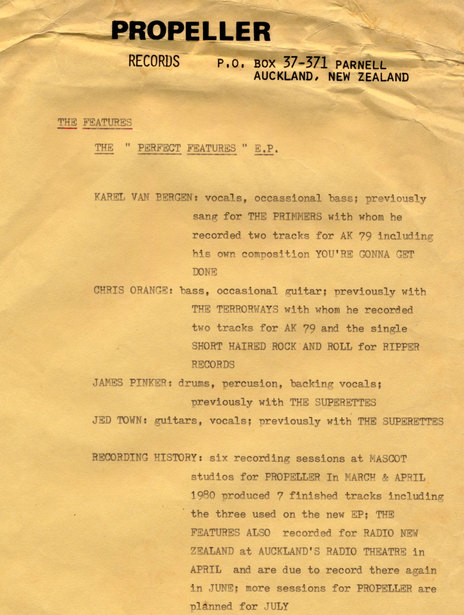

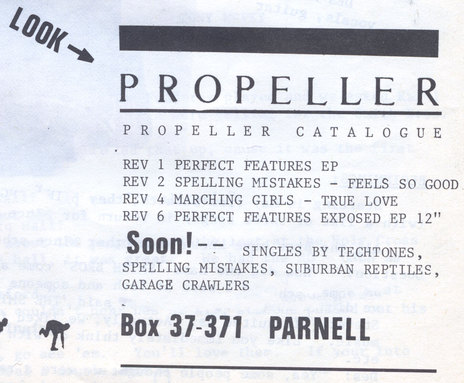

Propeller press release, April 1981. The Screaming Meemees single would not see release until July and the Techtones single remains unreleased.

The Screaming Meemees - See Me Go (1981)

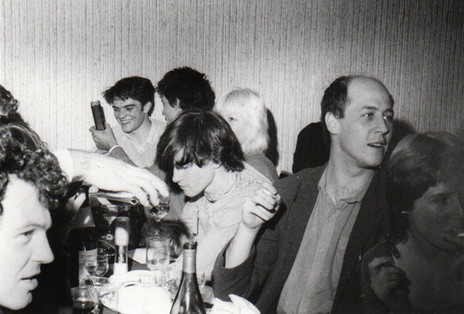

Don McGlashan, Paul Rose, The Newmatics' Syd Pasley, The Screaming Meemees' Tony Drumm, Syd's partner Angela, Simon Grigg and unknown, 1981. Taken at the NZ Music Awards, Logan Park, 1982, the year Grigg was given a special award for Outstanding Contribution to the New Music Industry.

Nathan Haines and Simon Grigg, Parnell, Auckland, 1995

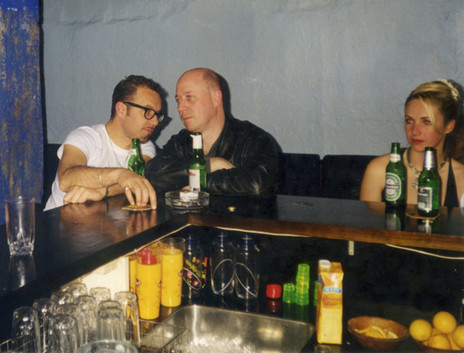

Simon Grigg in the early 1990s at Cause Celebre, the club he ran with Tom Sampson on Auckland's High Street

Photo credit:

Darryl Ward

Blam Blam Blam - There Is No Depression In New Zealand (1981)

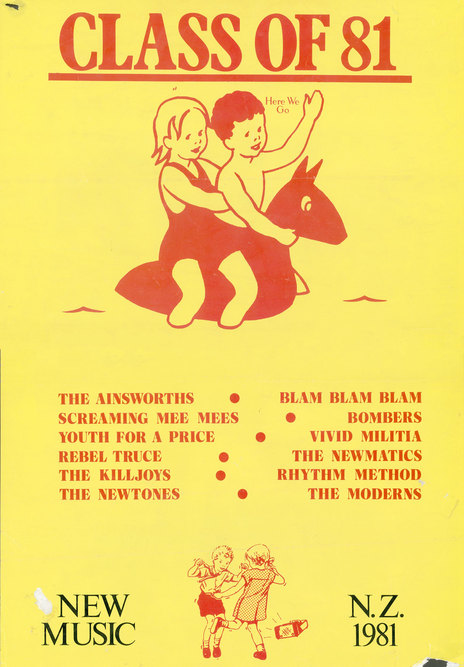

Poster for the March 1981 Class Of 81 compilation of new bands, designed by Terence Hogan

SImon Grigg and Mark Phillips at the launch of their Stimulant dance compilation Eight Arms to Hold You, at the Brat nightclub, Auckland, 1986. Photograph by Murray Cammick

Simon Grigg with Tim Mahon of Blam Blam Blam, on the ferry to Picton the morning after the violent Victoria University concert during the Screaming Blam-matic Roadshow, July 1981. Photo by Jenny Pullar

Photo credit:

Jenny Pullar

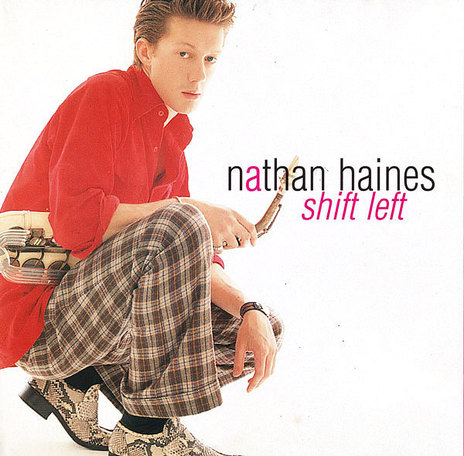

The second sleeve for Shift Left, December 1995.

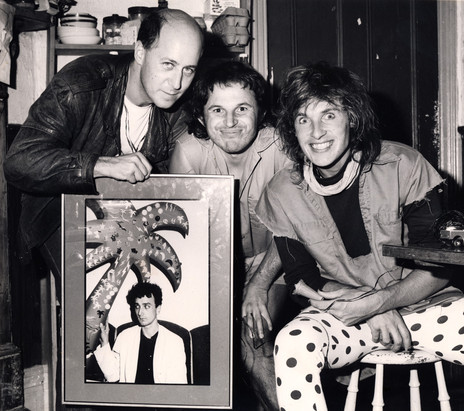

Simon Grigg, Chris Knox and Andrew Fagan, possibly taken in the 1990s for a Real Groove article. In the frame is Andrew Snoid

Photo credit:

Bryan Staff

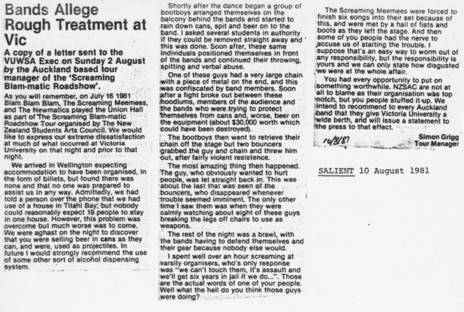

The manager of the Screaming Blam-matic Roadshow complains to Salient about the bands' rough treatment at Victoria University, August 1981

Platinum discs for OMC's second single Right On - Alan Jansson, Simon Grigg, Pauly Fuemana, at Hotel D'Vin, 1996

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

Michael O'Neill of the Screaming Meemees with Simon Grigg, Devonport 1982. Photo by Jim Abbott

Photo credit:

Jim Abbott

Simon Grigg and Peter van der Fluit of the Screaming Meemees, on the door at the North Shore Netball Club, 27 March 1981. Photo by Murray Cammick

Photo credit:

Murray Cammick

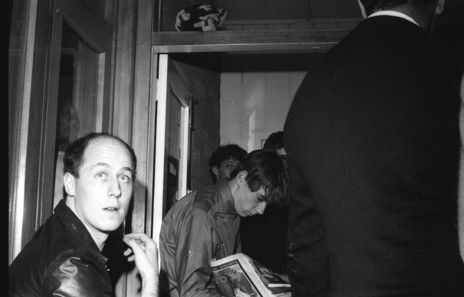

Iggy Pop at Taste Records, Auckland, 1979. David Herkt to Iggy's left. At the back wall, designer Terence Hogan (AK79, Class of 81, Toy Love etc.) Behind the counter is Simon Grigg

Photo credit:

Photo by Chris Slane

The original Propeller Records press release

Peter Urlich and Simon Grigg

Photo credit:

Photo by Michael Stuart.

Propeller advert in an Auckland fanzine, Loose Heads, November 1980

Anthony Ioasa with manager Simon Grigg (left), APRA Silver Scrolls, 1998

Simon Grigg, Pauly Fuemana, London, August 1996

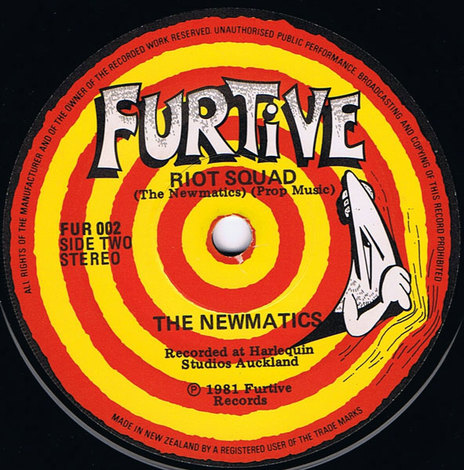

Furtive label

Photo credit:

Designed by Chris Knox.