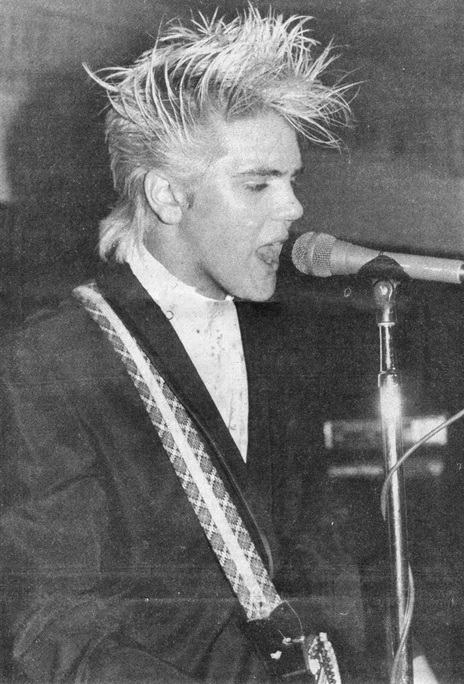

Michael O’Neill just laughed and went back to his scrubbing. Washing dishes out the back of Quays nightclub was a long way from feeling like a rock star.

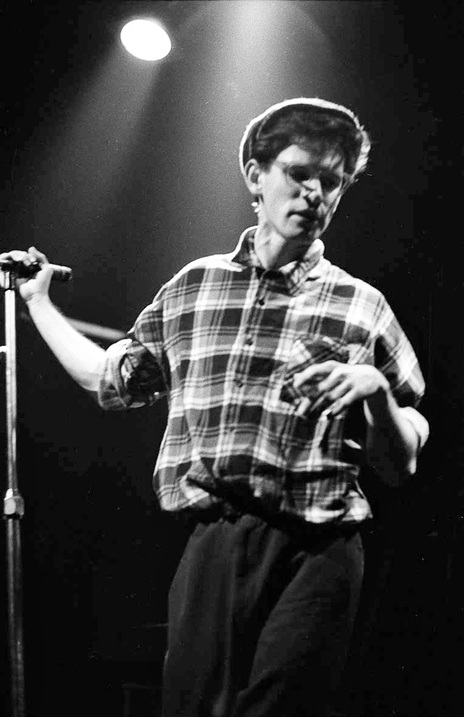

Only a few months earlier The Screaming Meemees had taken the 1983 Sweetwaters festival by storm. Their blinder of a set spotlit them as a band on the brink of greatness. It’s a memory anyone would hold dear, yet before their sweat had dried, they were looking at each other and thinking “Ah, fuck it.”

So, here he was, elbow deep in suds, earning his escape fund.

“And it turned out to be really good for me,’’ says O’Neill. “By the time I’d got to England I’d completely acclimatised, I’d left behind whatever bullshit I’d managed to blow up my arse. I had been a very serious young man who had totally bought into a particular aesthetic and played it quite well, but it was over.”

And he was barely 20. Which is totally punk, except for the bit about Tony Drumm’s aunty.

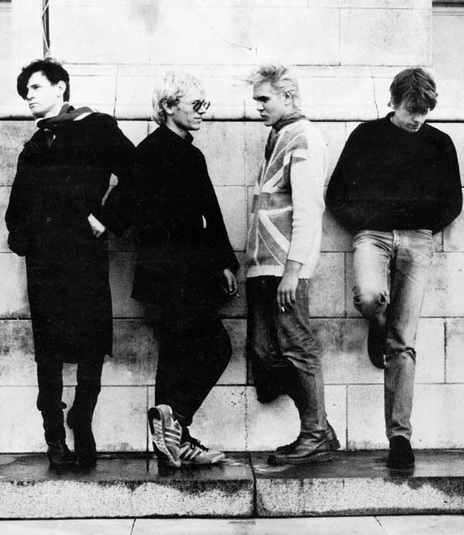

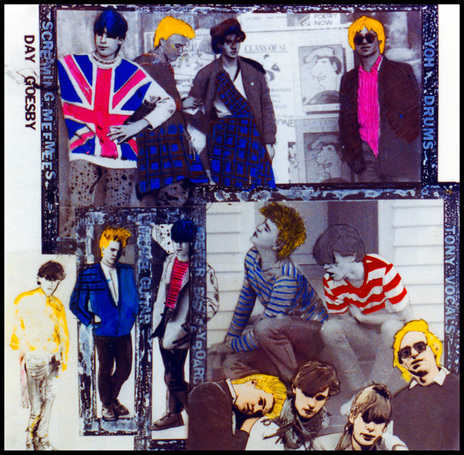

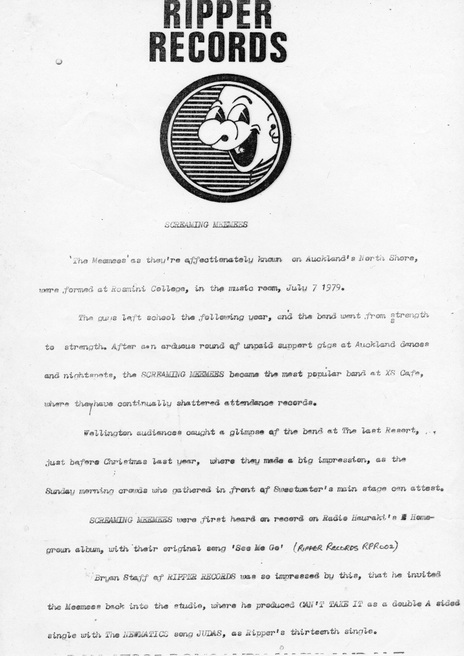

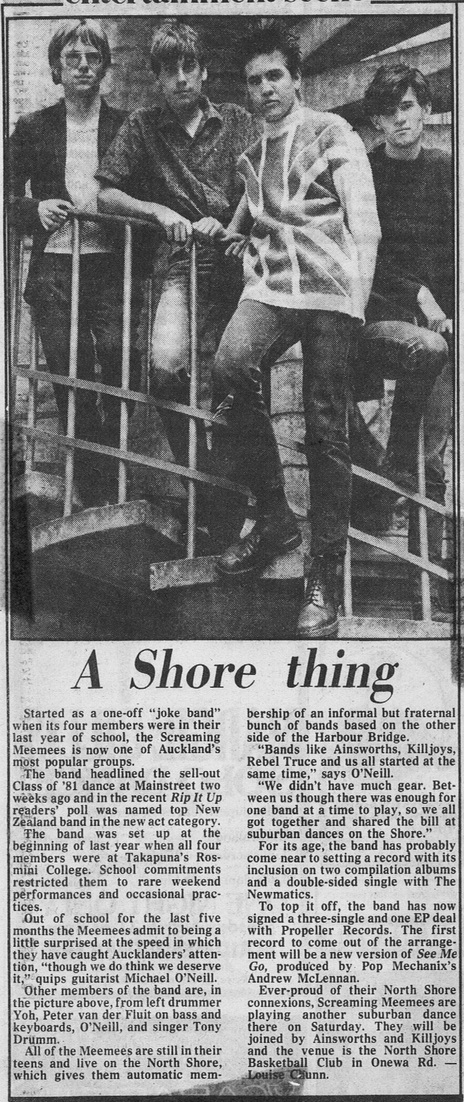

A seventh former, Drumm was one of the faces at Rosmini College on Auckland’s North Shore. Not that it was hard to stand out in a Catholic school devoted to rugby and packaging boys for university.

He was a savvy teen who, like other bored young Rosmini rebels such as Rowan Shedden (later with The Killjoys and The Dabs) and Nicolas Orange (brother of The Features’ Chris Orange), marked time in the school’s music room.

Drumm’s English aunt posted over a copy of the Sex Pistol’s Never Mind the Bollocks. He plugged into this new music straight away, says O’Neill. “Then he started buying Melody Maker, NME, all that.”

By the time a few other boys returned from UK holidays with Clash albums tucked under their arms, a micro punk revolution was well underway. Which was harder than it sounds. Even if the music mags were available, shipping meant they were at least three months old when they got here. Then any records they ordered would take another three months, meaning they were always more than six months behind.

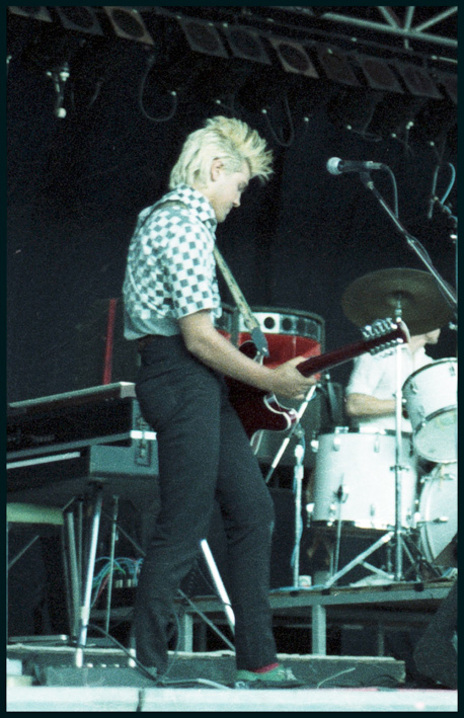

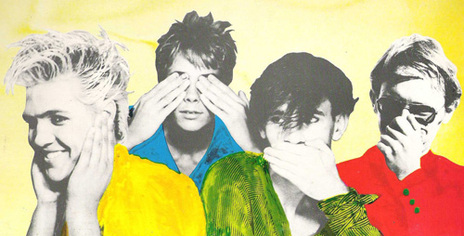

Looking the part was much easier. “Growing up with four sisters,” says O’Neill, “I’d become good [at sewing], so we’d hit the op shops and alter things ourselves ... I loved it, that whole thing of wanting something really badly but not being able to get it is fantastically creative, your mind fills in all the gaps.”

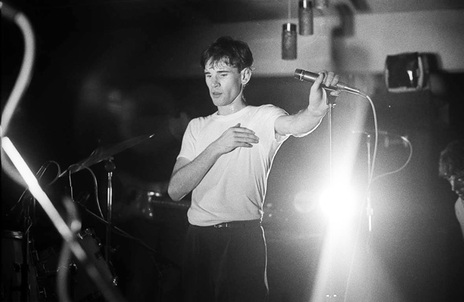

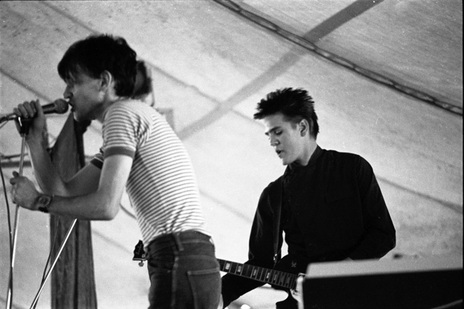

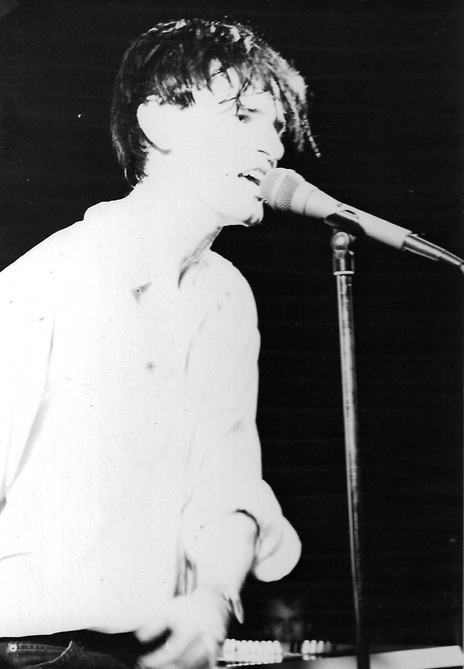

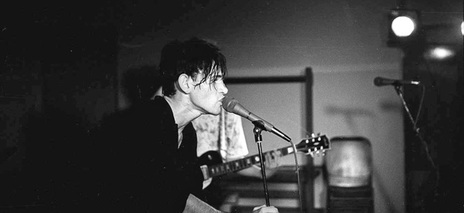

A school talent quest was Drumm’s chance to rark everyone up. From the start, it was clear this was his band and he’d be fronting it. But he couldn’t do it alone.

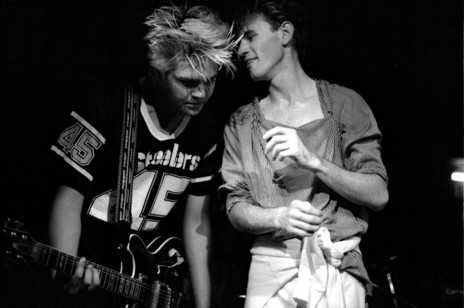

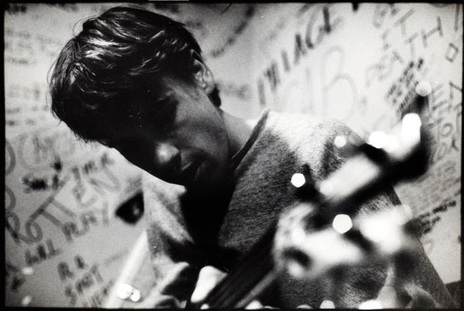

O’Neill was only in fifth form, and learning rhythm guitar from his brother Paul as they played along to his 1960s records in their bedroom. Paul had even converted a guitar so he could play it left-handed, Ziggy Stardust style.

Drumm wanted his best mate Hilary Hunt (later with The Ainsworths) on bass until it became clear that O’Neill’s classmate Peter van der Fluit would be a better option – he’d only played violin, but they had the same number of strings so how hard could it be?

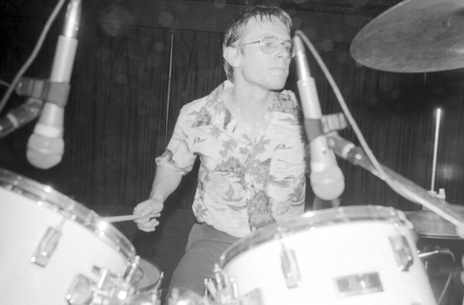

After recruiting the school orchestra’s drummer, Laurence Landwer-Johan, universally known as Yoh, they worked up versions The Rezillos’ ‘Somebody’s Going to get Their Head Kicked In Tonight’ and The Undertones’ ‘Teenage Kicks’, only for the freshly minted Screaming Meemees to come second to some kid playing ‘Classical Gas’.

“We loved it,” says O’Neill, “all of it, and we started practising every week at school.’’

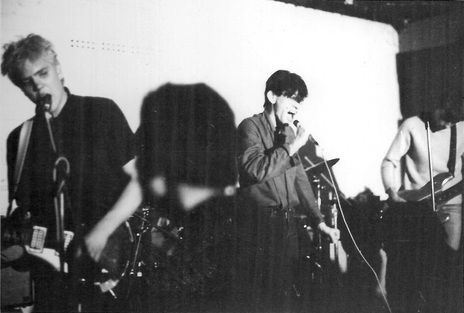

The Meemees scored a support slot at Squeeze, an unlicensed venue on Fanshawe St near the CBD and waterfront.

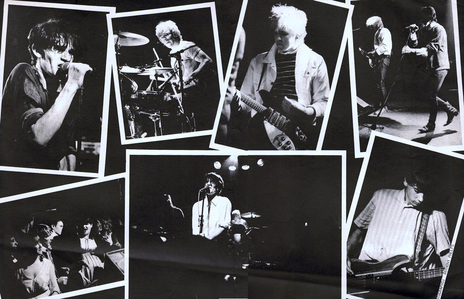

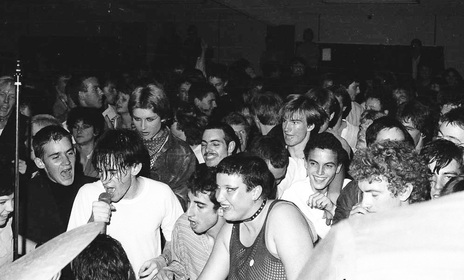

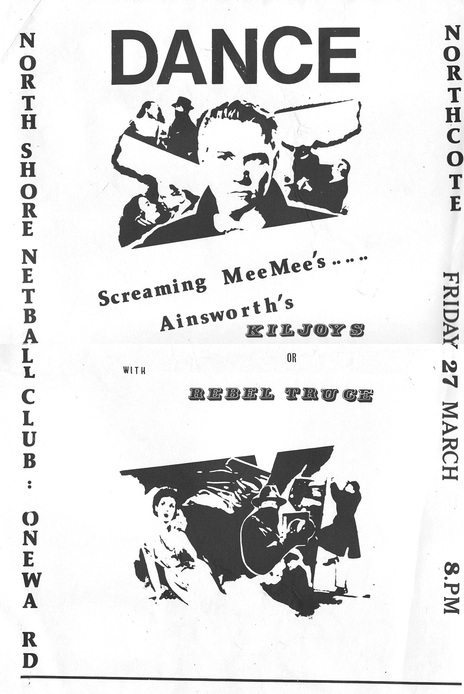

Their timing was ideal as Auckland’s live scene in 1980 was extremely active, if a little prone to skinheads. After developing their own flat-out brand of spiky pop at all-ages gigs, the Meemees scored a support slot at Squeeze, an unlicensed venue on Fanshawe St near the CBD and waterfront. Crossing the bridge was a big deal to everyone and venues quickly learned that when you got the Meemees you got a chunk of the North Shore’s youth as well.

“That made things much easier for us,” says O’Neill, “we always had great support.” (Sometimes from unexpected quarters: that first gig would never have happened if Th’ Dudes frontman, Peter Urlich, hadn’t handed over a set of bass strings.)

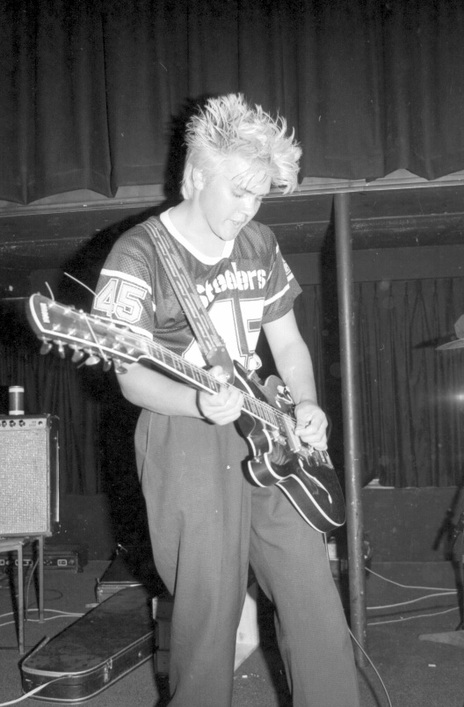

The decision to play originals was simple; writing was easier than working out someone else’s chords. Drumm would decide on a theme, then O’Neill would kick off a riff and they’d jam until something worked. Songs would be finished on stage, or totally reinvented. Yoh had a habit of forgetting how they went.

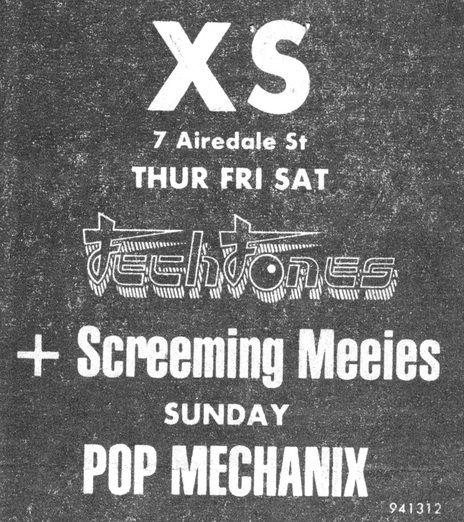

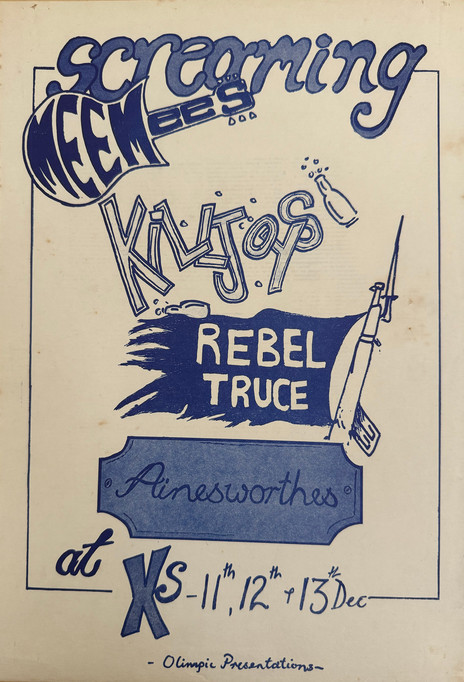

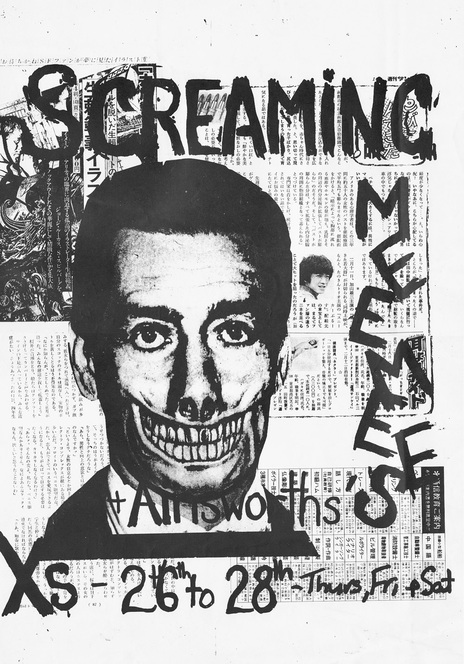

The band soon moved to other venues such as XS Cafe and Island of Real, all heady stuff for schoolboys.

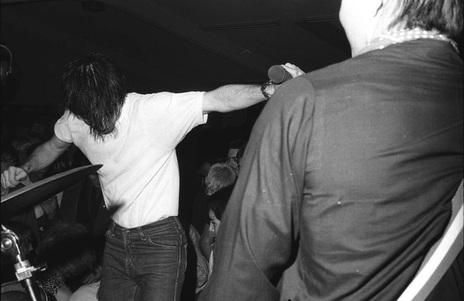

“It was just dangerous,” says van der Fluit, “we were physically scared every time we played, but it was also so outrageous and so much fun. The place was crawling with kids, on the stage, all over the speakers, it was madness and we‘d be shitting ourselves and hugely excited at the same time.’’

That wasn’t his only worry. As far as his mum, an Italian of fearsome repute, knew, he was swotting at Mike’s place. “I’d have to sneak my bass out the window before leaving.”

The next stop was Yoh’s home above the Mairangi Park Tavern. He’d shimmy down a drainpipe to escape, which was a great plan except for the times he forgot his glasses.

“We thought we were so bloody clever,’’ says O’Neill, “until Pete’s mum saw the review in the paper."

“We thought we were so bloody clever,’’ says O’Neill, “until Pete’s mum saw the review in the paper. That got him a severe clip round the ear.”

It wasn’t a fight they were going to win so their parents eventually settled for the assurance – and as long as they were home by 10.30pm – that Mike and Pete would look after each other.

“We didn’t tell them the skinheads wanted to kill us,’’ says van der Fluit. “Those gigs, the atmosphere was just brooding, always on the point of erupting, but the danger wasn’t so much the playing, it was the getting in and getting out again, that’s when they’d get us.”

Their sense of exposure became all too real when a fan was greviously injured as the Meemees were playing at Highbury RSA on the Shore, but things settled down once the skins realised the band brought girls with them, lots of them. Now there was novelty.

The Ainsworths' Adam Holt recalls "It cast a terrible pall over the scene and It sort of marked the end of the boot boy era. The bands started to break up and we spent more time at clubs than gigs - it seemed safer and a bit more joyous."

Even so, O’Neill remembers one night, when he was walking to a gig in his brand new cherry red Dr Martens boots, a skinhead tipped him upside down.

“He was tapping my head against the footpath – I remember being worried about my hair – but I wasn’t giving my boots up. They were bloody expensive and they’d taken six months to get here.”

It didn’t seem to matter that they were only size 8 1/2: “He said he’d wear them as earrings and told me to stop curling my toes ... at that point in the negotiation I realised that if I protested any more I was going to get another hiding. I played in my socks.”

It was a price worth paying. The band were playing regularly, up to four times a week, a rate increasingly reflected in their declining school attendance. It eventually cost them their University Entrance accreditation.

“We didn’t care, we were so earnestly serious about the music,’’ says O’Neill, “it was everything, our weekly buzz, our social life, and very quickly we made a conscious decision, as 16-year-olds who knew everything, to be a real band. We were all chin out, chest out, like we knew exactly what we’re doing when we didn’t have any idea at all.”

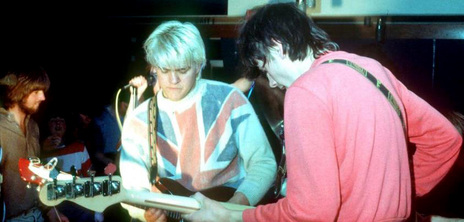

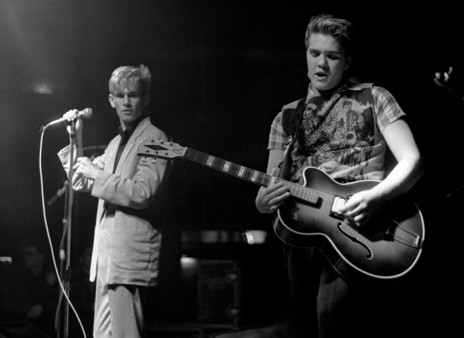

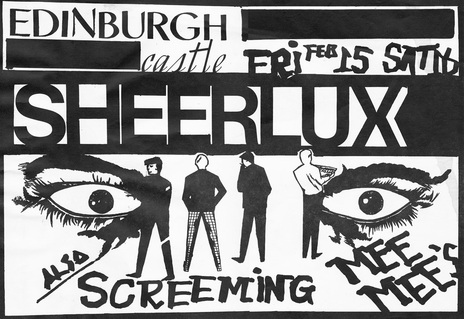

That began to change in late 1980 with the offer of a three-month slot supporting The Swingers, who were breaking in a new set at the Liberty Stage, above the Edinburgh Castle on Symonds St.

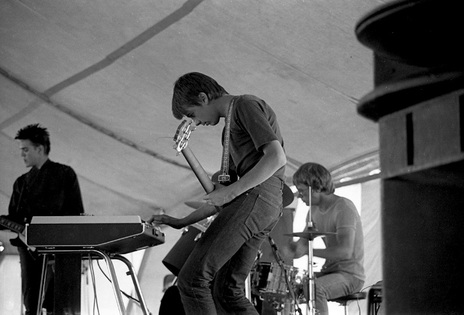

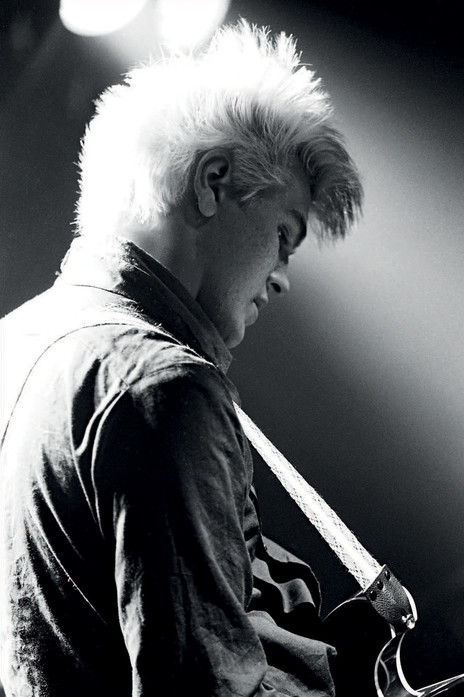

“That took us from a school band to The Screaming Meemees,” says O’Neill. “Watching someone like Phil Judd, who had such control over his gear and worked the stage the way he did, that was the first time we got to engage with really good musicians. They could have just ignored us, they saw how nervous and green we were, and we were full of stupid questions, but they took us under their wings.”

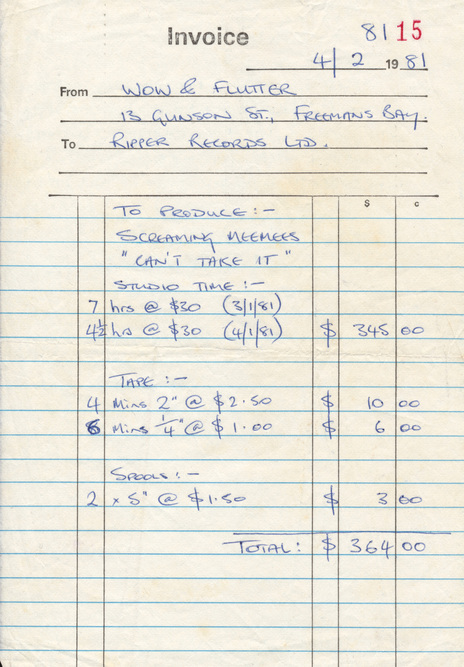

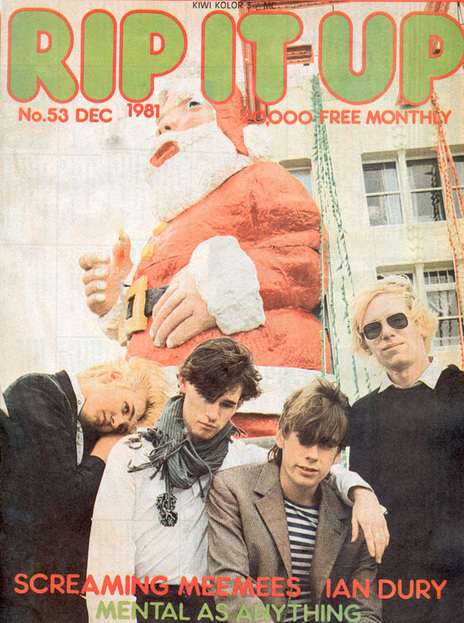

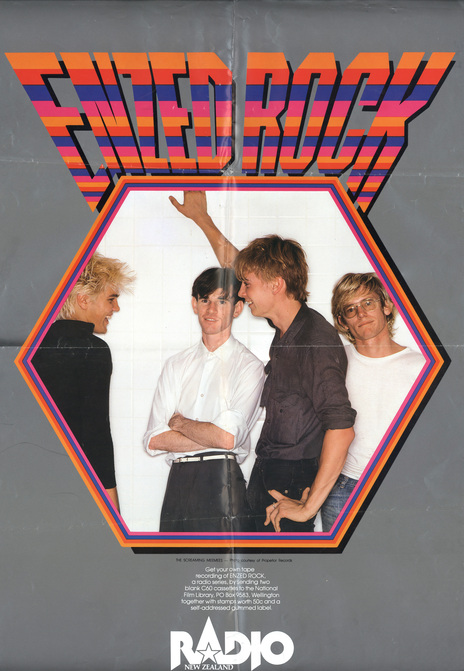

They had their first studio experience when Ripper Records owner Bryan Staff recorded ‘Can’t Take It’ for a double A-side single with The Newmatics’ ‘Judas’ (it later became the theme to teen music show Droppa Kulcha). It entered the lower regions of the Top 40 in April 1981, but by then the band had moved on.

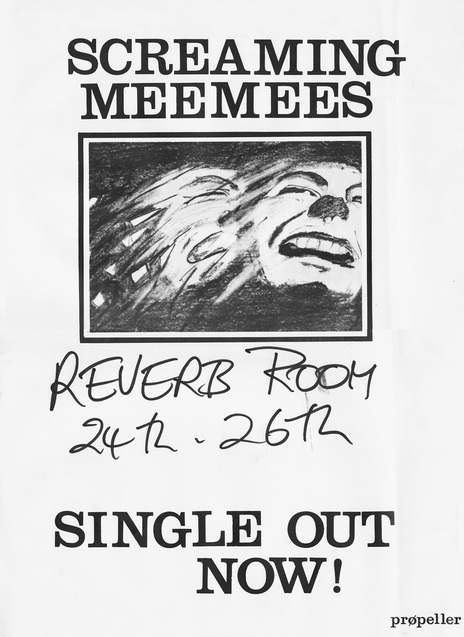

They were approached by Simon Grigg to sign to his Propeller label, who featured a demo version of ‘All Dressed Up’ on his seminal Class of 81 compilation. A further demo of ‘See Me Go’ ended up on a compilation from Ripper Records and Radio Hauraki.

Grigg’s association with the band rapidly grew to where he reluctantly became their manager.

If choosing live favourite ‘See Me Go’ as their first single was easy, matching the spirit of the original demo wasn’t.

“We needed someone who could say, ‘This is how it works, this is what can happen,’ ” says O’Neill, “and, well, Simon looked older, because he was balding I guess, so everyone took what he said seriously. It was a total shock when we found out he wasn’t that much older than us and he’d been making it up as he went along.”

If choosing live favourite ‘See Me Go’ as their first single was easy, matching the spirit of the original demo wasn’t. Multiple versions were recorded at Harlequin Studio with Pop Mechanix vocalist Andrew Snoid (AKA Andrew McLennan) as producer.

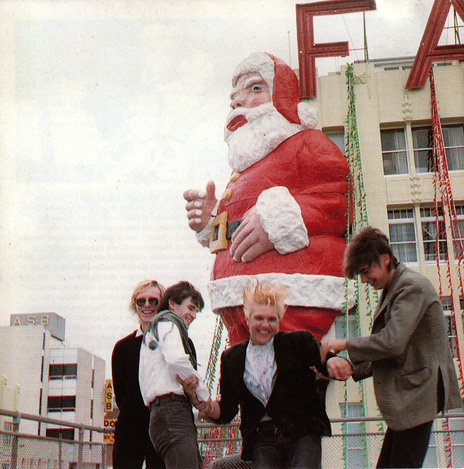

Then, after the buzz kill of school exams, they headed off on tour, the first time any of them had been away from their parents. As they were the youngest touring band in the country, Grigg was forced to become as much a surrogate parent as he was manager.

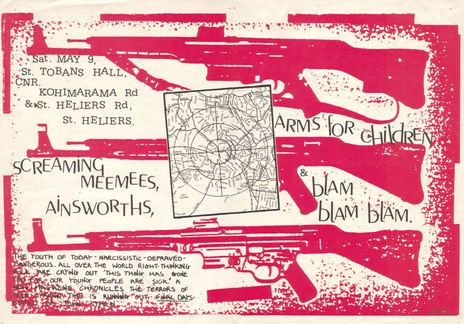

Then in July 1981, with the buzz around the group building, they joined the Screaming Blam-matic tour, a Propeller Records showcase featuring the Meemees, Blam Blam Blam and The Newmatics. Their itinerary dropped them into the mayhem of the Springbok Rugby Tour.

Being part Māori, O’Neill instinctively opposed the tour going ahead, but other than that, he hadn’t given it much thought. “I don’t think any of us were radicals or anything like that,’’ says O’Neill, “we were too young, and really, we were only out there playing for ourselves anyway. But everyone expected us to share their political leanings and I don’t think we had any ... we were more interested in looking up at the stars, we were literally in awe of New Zealand.”

They were in Christchurch when the ‘See Me Go’ test pressings finally arrived. They were leapt upon and then binned just as quickly.

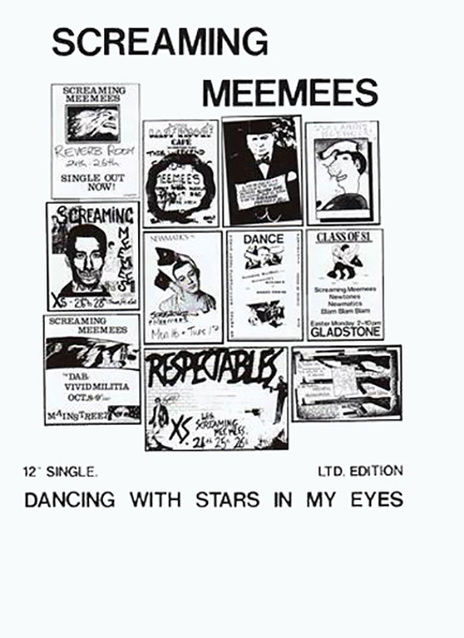

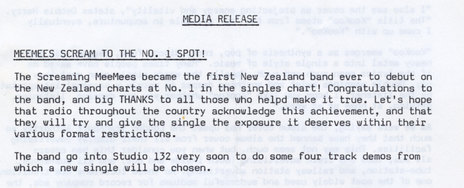

A marketing manager at distributor Festival Records had taken it upon himself to remix the track on his own, leading to disaster. Grigg had no choice but to stop the pressing and reinstate the correct version which, upon release, went gangbusters. The 500 limited release 12-inch sold out within 24 hours, with another all the 7-inch copies pressed sold by the end of the week. It was then deleted from the catalogue by Grigg.

“Had we been older,” says van der Fluit, “we might have been more impressed. I think we said ‘whatever’.”

“We were supposed to be punk” says O’Neill, “outside the establishment, outside everything ... but really we didn’t have any idea what it meant, I think our first thought was that it might mean we could play in proper venues ... so it really didn’t seem like a big deal.”

Their swift success didn’t curry favour with some of the industry’s older hands either, who dismissed their achievement, to their faces, as a fluke.

But they found a true fan in Prince Tui Teka. The Meemees were frocked up and in a belligerent mood at the New Zealand Music Awards (they were named Best New Band) when the big man walked over.

“What are you guys rebelling against?” he asked as he grabbed a chair.

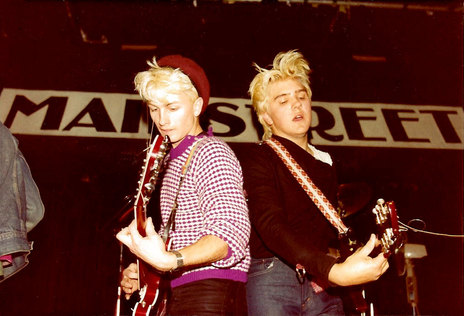

“He got us completely,’’ says O’Neill. “You ask me now who our biggest supporter was, it was that amazing man, a legend. He really stood up for us, and who would have thought? A guy like that ... I mean he was a total showman, so he saw our outfits as costumes, he got the energy.” Even Dalvanius Prime checked the Meemees out at Mainstreet on his say-so.

Tui Teka’s approval also cast a veil of protection over the band wherever they appeared, especially in tiny North Island towns like Manaia, near Hawera. It looked like the entire town had packed into the town hall, mostly, the band thought, to gawk at the weirdos. But they won over a new set of fans by allowing the local kids to bash about on their gear once the gig was over.

Curiosity was a common reaction. The Meemees were relaxing in a bar in Invercargill when a local got on the phone to tell his wife about what he’d seen.

“You’ve got to come down darl, they look like freaks ...” he said before leaning over to offer a quick, “hey, no offence fullas” and then going back to amazing his missus.

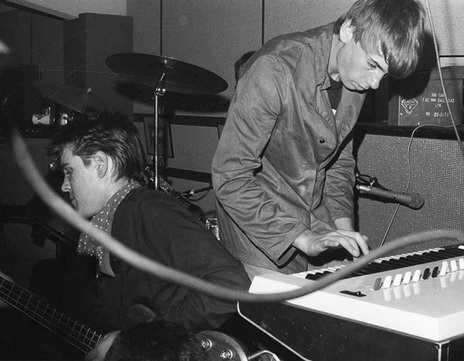

But as much as they enjoyed the travel, the daily grind of touring wore them down and they settled on playing bigger gigs less often, in turn opening up time for an album.

The sessions quickly became an ongoing party, which was great fun unless you were funding them.

Anyone expecting them to simply record the songs that had made them one of the biggest bands in the land didn’t know the Meemees. “We got that a lot when it came out,’’ says O’Neill. “Where are the classics? I don’t think it was a conscious decision, we never sat down and talked about anything before doing it, but it felt exciting writing songs that were unexpected. We had this mindset of ‘this can’t last forever, so make the most of it.’ Success happens to other people and we weren’t feeling all that successful ourselves, we just loved writing new stuff, like it became our drug. Out with the old."

The sessions quickly became an ongoing party, which was great fun unless you were funding them. After calculating they needed to sell about 10,000 copies just to break even, an unheard of number for a local indie release, Grigg finally cracked the whip. But optimism was high when the first single ‘Sunday Boys’ went to No.1 in Auckland, and 11 nationally.

“That was U2,” says O’Neill, “I’ll admit that, and it wasn’t even finished it when we first played it. We had a verse and no chorus, so we played that for about five minutes with Tony mucking around and the audience loved it. That was how we did things really.”

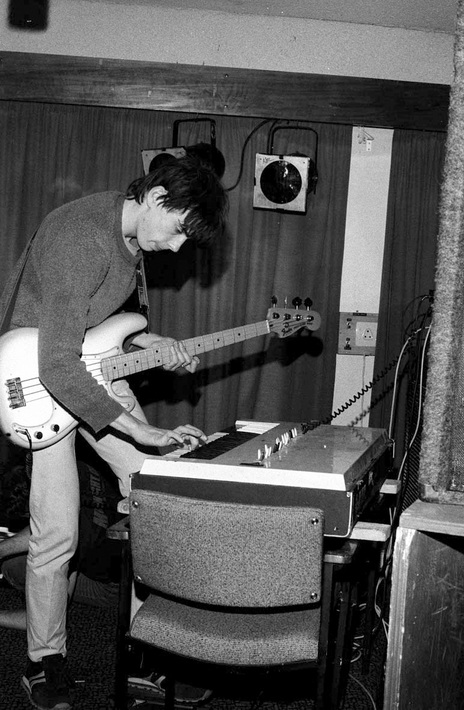

But, if ‘Sunday Boys’ distilled their stock in trade of poppy sing-alongs, tracks like ‘Days Goes By’, ‘F is for Fear’ and ‘Dali’s Moustache’ – propelled by van der Fluit’s rapidly improving bass playing – were all about the funkier edge of English post-punk such as Rip, Rig and Panic and Pigbag. They sounded completely different to the band that had recorded ‘See Me Go’, which was barely a year old.

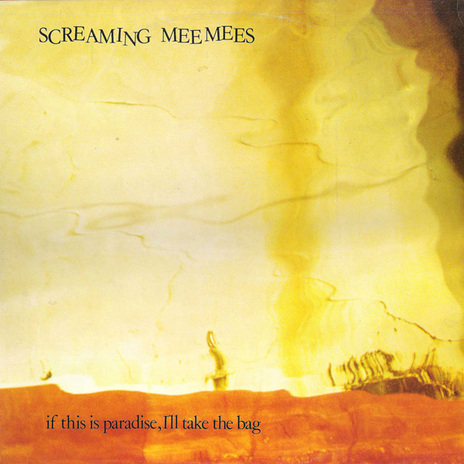

Released in 1982, If This is Paradise, I’ll Take the Bag charted at No.15, but it left Propeller deep in debt.

Released in 1982, If This is Paradise, I’ll Take the Bag charted at No.8, eventually going gold.

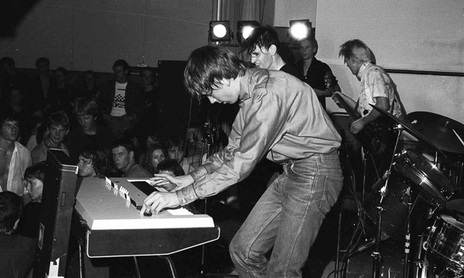

It all seemed to be worth it when they took the stage for the 1983 Sweetwaters festival. It was their third appearance. In 1981 they played at 10.30am to a crowd laying in their sleeping bags, in 1982 they were moved to 5pm, then by 1983 they were given a prime 8pm slot, in between INXS and the Psychedelic Furs.

“I remember standing on stage as the sunset,” says van der Fluit, “and this farm bike, silhouetted with a dog chasing along behind, was moving over the hills. Just amazing ...”

The crowd was onside from the moment Drumm announced the news from the Black Caps-Australia cricket one-dayer. Which didn’t stop the show from being the usual tightrope walk. “It was always a 50/ 50 chance that we’d play well,’’ says van der Fluit. “It created a bit of anxiety because we never knew what would happen and we were never good with setlists, Tony was just great at reading a crowd, at any moment he’d segue from what we were playing into Sinatra or some other ridiculous tangent.”

On this day, it worked to perfection.

“It confirmed emotionally and musically that we were on the right path,” says O’Neill. “We had something unique that could work with a stadium-sized crowd and I’d say anyone there who hadn’t heard us before would have walked away thinking we were pretty bloody good.”

So, what happened afterwards?

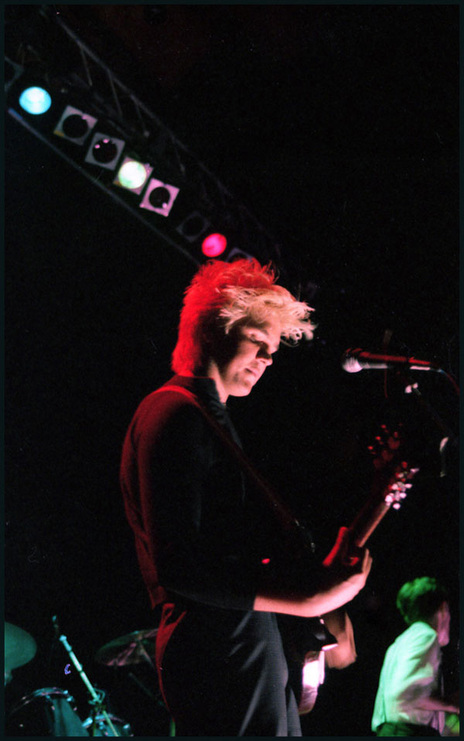

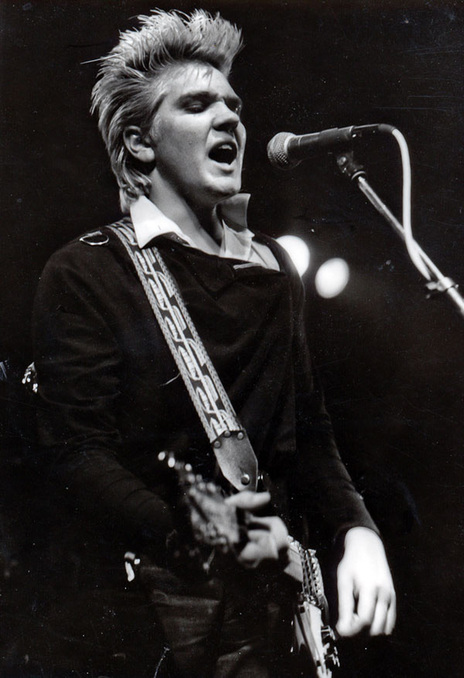

Memories vary, but by now O’Neill was only one excuse away from packing it in. He’d already walked once while recording their final 12” single, ‘Stars in My Eyes’, a track inspired by UK band ABC and possibly their finest recorded moment.

The guitarist was tired and things between he and Drumm had been difficult since the singer had broken up with his girlfriend, who happened to be O'Neill's sister. “That was a disaster, and I didn’t really want to see any of it.”

The shows broke the venue’s attendance records with queues stretching down Queen St.

There was a bit of guilt in the mix as well as he’d promised his father, a police superintendent, that he’d look out for his sisters. On top of that, his 26-year-old brother, Paul, had died after drug issues landed him in jail. “He’d given music to me in the first place, what a wonderful gift to give someone.”

“So that was an interesting time for me, but more than anything we had all changed, bands do that. We didn’t break up for one reason, there were lots of them. I had this realisation that I enjoyed creating more than performing and it hadn’t occurred to me before that I even had that choice. It was odd though, because outside of the band we didn’t have many outlets for discussing these things. Even if we didn’t feel it, people looked at us as successful and thought that meant we must have it all together as well ... after Paul died I didn’t want anything to do with music for a while, I wanted to get away. We’d given it the best three years we could have and it had felt really important the whole time, but it was over. I guess I retired at 19.”

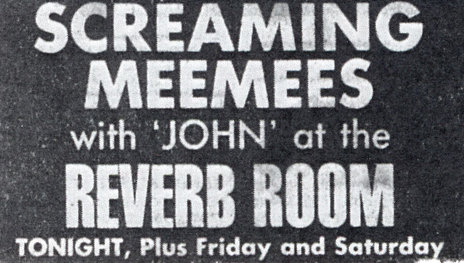

Breaking up wasn’t that easy, not when bills needed paying, and Grigg cajoled them into two fundraising shows at Mainstreet.

“I really didn’t want to play,’’ says O’Neill. “But, in the end, and as pathetic as it sounds, I said I’d do it if he gave me his Lady Penelope Dinky car.”

The shows broke the venue’s attendance records with queues stretching down Queen St. The Meemees last appeared together at O’Neill’s first wedding, and that was it. From beginning to end they shared three hugely formative years and, says O’Neill, they will never go back.

“Back then being in a band was taboo, it was seen as something quite nasty, and that only made it more fun. Now being in a band is part of the third form syllabus, which, to me, defeats the whole purpose of rock and roll. If we’d always been professional musicians then it might be different, but we weren’t, we really loved the aesthetic and I think we achieved what we set out to achieve. Then we grew up.”

--

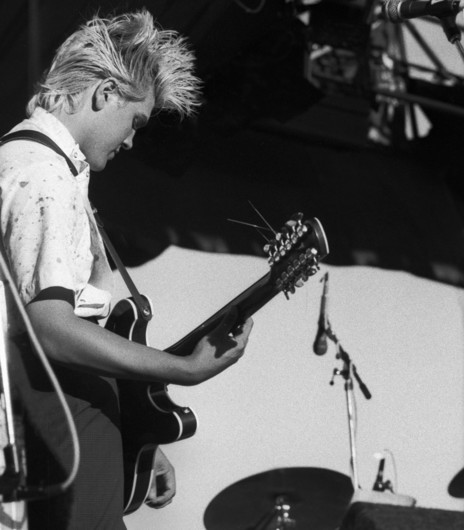

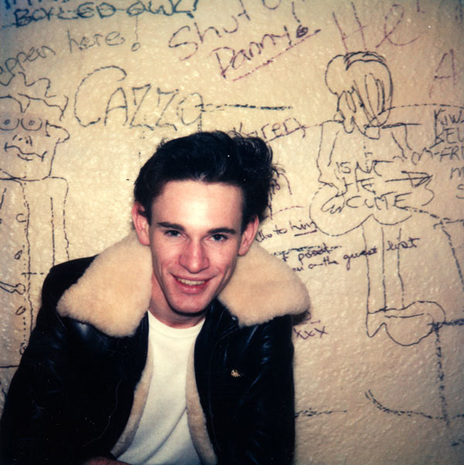

Michael O’Neill died, of cancer, on 4 December 2025. His friend Simon Grigg – who released the Screaming Meemees on the Propeller label – wrote, “While the entire band, in large part, defined an era in New Zealand music, it was guitarist Michael who was the band's heart and soul and a major reason why thousands queued to see them. Their second single, ‘See Me Go’, was the very first local record (album or single) to enter the New Zealand charts at No.1, and the band still held the record for the biggest crowd ever at Auckland’s Mainstreet when it closed.

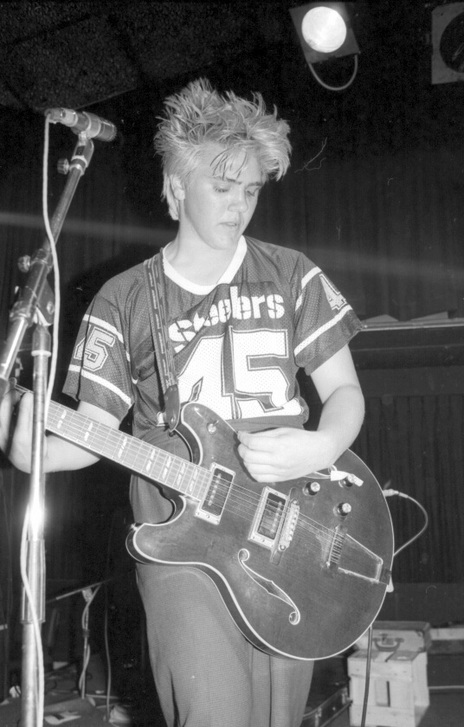

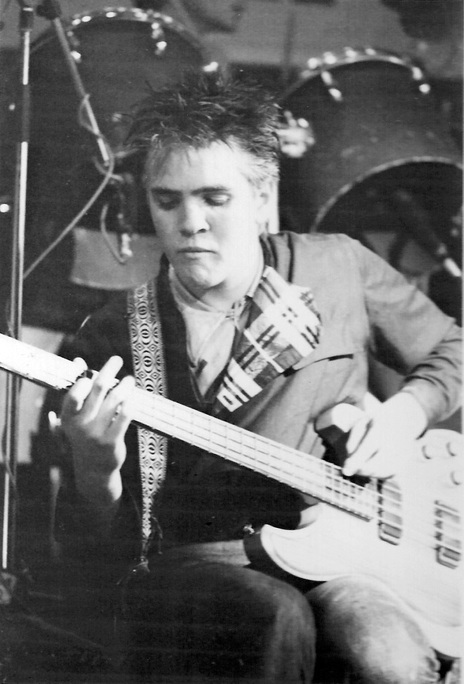

“But it was much more than that. The band’s music spoke to a generation, and a big part of that was Mike, the sounds he co-wrote with the others and played on that trademark cherry-red Rickenbacker.

“After the band split in 1983, Mike moved into clothing design, and his Cutter of Newton clothing brand was ubiquitous in inner-city Auckland later that decade. However, his first love was always music, and he returned in 1989 with the gorgeous guitar-pop of These Wilding Ways, and in the 1990s, he founded Liquid Recording Studio with Peter van der Fluit from the Meemees. His studio work was everywhere over the next couple of decades.”