From modest but potent beginnings – see part one, Film Music Aotearoa, 1930s-1960s – the 1970s saw local audiences start to become more interested in New Zealand-made film.

Sleeping Dogs ushered in a new era of film-making, and the emergence of an experimental film scene spawned a director/composer dream team and a noteworthy film controversy.

Electronics began to infiltrate New Zealand’s film scores, and major players of the Aotearoa music scene made contributions to soundtracks and scores. Blerta members in particular were all over film, and Blerta pianist John Charles turned his hand to composition, creating the first of his many scores.

These are some key moments of 1970s New Zealand film music. (With a few exceptions, this overview concentrates on music written specifically for films – scores – rather than pre-existing songs.)

An early climax in Hugh Macdonald's This is New Zealand. To watch this excerpt, go to New Zealand On Screen.

Scenic sensorium

For the impact of its music, mention should be made of Hugh Macdonald’s This is New Zealand (1970), a promotional sensorium made for Expo 70 held in Osaka, Japan. Over 350,000 New Zealanders saw it on its homecoming theatrical release, and few would have left without an increased awareness of soundtracks. The music was the star as much as the scenery, especially a breath-taking aerial shot of Aoraki/Mt Cook to the Karelia Suite by Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. Also on the soundtrack was music by The Acme Sausage Company (Geoff Murphy and some future members of Blerta), The Avengers, and the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band.

Debut film score of Blerta pianist

The score of the TV movie The God Boy (1976) – directed by Murray Reece and based on the book by New Zealand author Ian Cross – is significant, as it was composer John Charles’s first significant project. Charles became better-known for his collaborations with director Geoff Murphy; as well as being a member of Blerta, Charles created scores for Murphy’s seminal New Zealand films, which they would begin working on a few years later.

The God Boy, a coming-of-age psychodrama set in small-town 1950s New Zealand, was made to mark TVNZ’s first 25 years and was the first feature-length project created for New Zealand television. Charles’s soundtrack was performed by members of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, conducted by William Southgate.

As well as orchestral music with great melodies, Charles also makes effective use of non-standard instrumental effects. A recurring rising and falling, sliding string motif depicts and amplifies 13-year-old Jimmy’s inner tension between his strict Catholic upbringing and his all-too-earthly personal troubles.

Early use of electronic music in a New Zealand film

David Blyth’s 13-minute experimental short film Circadian Rhythms (1976) was an early example of the use of electronics in a New Zealand score, though the music wasn’t written especially for the film. ‘Horizons’ by Ross Harris was originally composed in 1974 to accompany a mural by New Zealand painter and fellow-composer, Michael Smither. Harris created ‘Horizons’ on equipment in the Electronic Music Studio at Wellington’s Victoria University. He studied electronic composition with Douglas Lilburn, who set up the studio in the mid 60s after realising the possibilities of electronics in contemporary classical music. At this time, electronics had been used for decades by European and US art-music composers and Lilburn wanted the technology available to New Zealand composers as well.

Overseas, electronics had found its way into the scores of films to great effect since the early days of sound. The otherworldly colour and texture added by electronics was especially suited to sci-fi film scores, often blended with acoustic instruments.

• Watch Circadian Rhythms at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Blyth’s short psychosexual drama, Circadian Rhythms, was more surrealist than sci-fi, influenced by both J. G. Ballard’s novel Crash (1973) and Dali and Buñuel’s surrealist film Un Chien Andalou (1929). Harris’s electroacoustic composition ‘Horizons’ contrasts percussive, industrial pulses with washes of electroacoustically processed field recordings of the natural world and was an inspired choice to accompany and enhance Blyth’s dark, dream-like, sometimes orgiastic images. Kiwi Pacific Records released ‘Horizons’ as a commercial recording in 1977.

Higher Trails

Although the bulk of its music was by Americans, the unforgettable use of John Hanlon’s song ‘Higher Trails’ in Michael Firth’s documentary Off The Edge (1976), deserves a special mention. The song was released on Hanlon’s 1975 album Higher Trails, and received a prominent placement in Off The Edge’s beautifully shot climax. The film was described as “Michael Firth’s ode to the exhilaration of adventuring on the spine of the Southern Alps.” Whether late 70s viewers saw the film at the cinema or, as one climbing enthusiast fondly recalls, “sitting amongst a bunch of mouldy climbers late one night in the back room of the Mt Cook visitors’ centre,” many warmly remember Hanlon’s song soaring over the film’s finale as the two adventurers launch off the mountain’s edge on skis and hang gliders.

Hanlon’s words and uplifting music were such a perfect accompaniment to the men gliding above snow-covered slopes, it’s difficult to believe the song wasn’t made to order. The song became an intrinsic part of putting the film together and the scene was edited around it. On his blog, in 2022, Hanlon wrote, “I knew Mike Firth [the] producer/director who made the movie and Jeff and Blair the Canadian hang-gliding skiers who featured in it. As the film was coming together so was my song. I suggested I had the perfect song for the movie and it proved to be true.”

The creation of the rest of the film’s music was taken off-shore. The carefree and tuneful instrumental score, filled with folky acoustic guitar, flute, synths and wah-wah pedal-infused electric guitar, sounds exactly as you might think if someone said, “1970s stock-production music for a ski movie”. In the best possible way. The score was created by American composers Richard Clements (Laverne and Shirley, The Six Million Dollar Man) and Richard Degray. Off The Edge was nominated for best documentary feature at the 1977 Academy Awards.

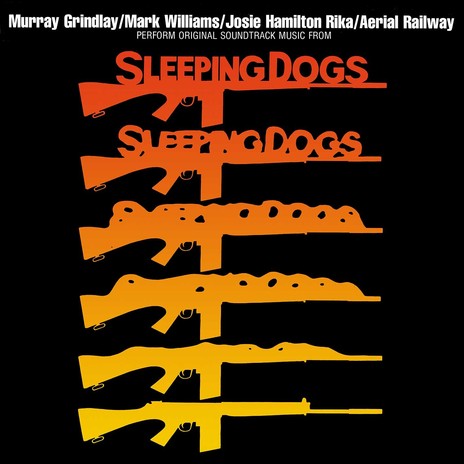

Sleeping Dogs soundtrack (EMI, 1977). Arrangements were by Murray Grindlay, Dave Calder, and Matthew Brown.

New Zealand film finally gets a piece of the action

When Roger Donaldson’s Sleeping Dogs hit the screens in 1977 it drew eager movie-goers into cinemas. The groundbreaking action thriller, based on C K Stead’s novel Smith’s Dream, “almost single-handedly crested a climate of acceptance within the country for a Kiwi film industry.” (Jonathan Dowling, Evening Post, 27 Feb 1988)

The film’s soundtrack was a mixture of especially composed country- or gospel-inspired pop songs and an instrumental score. Three songs were composed by singer-songwriter Murray Grindlay, and two songs (‘Sleeping Dogs’ and ‘Going To Coromandel’) were written by Waikato-raised David Calder of the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band. Calder also composed the bulk of the instrumental score. As well as Grindlay, the songs were performed by Mark Williams, Josie Rika, and Auckland pop group Ariel Railway.

Incidental music is used sparsely but effectively throughout Sleeping Dogs. Frenetic jazz-tinged piano (often accompanied by driving low strings) recurs throughout the film to move the action forward as Smith, played by Sam Neill, becomes unwittingly involved in the nation’s violent civil war despite doing everything he can to avoid it.

The Sleeping Dogs soundtrack, released by EMI in 1977, included the film’s songs, and just one instrumental piece from the score: ‘Smith’s Theme’ for oboe and piano. This was composed for the film by pianist Matthew Brown in partnership with New Zealand Symphony Orchestra oboist, Ron Webb.

Sleeping Dogs heralded a new wave of New Zealand cinema and paved the way for many more local filmmakers and composers to get their creations out into the world.

Folk-tinged soundtrack receives international award

1977 saw Tony Williams direct his first feature film. Solo was a romance about a hitchhiker and the pilot of a fire-patrol plane, set in a country town and infused with counterculture ideas of the time.

In the intervening years since his experimental short The Sound of Seeing, Williams had become one of the main creative forces behind Pacific Films, tirelessly directing television programmes and commercials. After his stint at Pacific, he directed the memorable Crunchie Bar “Great Train Robbery” ad with frequent collaborator, Murray Grindlay.

Dave Fraser, photographed by K E Niven, 1967. Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-215042-F

For Solo, Williams brought in multi-instrumentalist Dave Fraser as one of the film’s three composers; he had been the drummer in the Nick Smith Trio who performed in The Sound of Seeing in the 1960s. Fraser described his film work as a natural extension of his diverse jazz and pop career. Solo was his first feature film project as composer, and he shared the role with folk musicians Marion Arts and Robbie Lavën, members of Waikato band The Red Hot Peppers.

Solo’s folk-tinged score went on to win the 1978 Asian Film Festival’s “Merlion Award for Most Outstanding Music”. The soundtrack was released by EMI that same year. Fraser went on to compose the music for Beyond Reasonable Doubt (1980).

Blerta’s missing link

Although Dave Fraser hadn’t been a student at Wellington’s Victoria University, he was part of its Jazz Club, where his friends included Blerta members Geoff Murphy, Bruno Lawrence and John Charles.

When Blerta created its first feature film, Wild Man in 1977, Fraser was one of the many musicians who contributed to the Blerta-composed and -performed soundtrack. Other performers included the film’s main actor Bruno Lawrence on percussion and vocals, John Charles on piano, Beaver on vocals, and director Geoff Murphy on vocals and trumpet.

Wild Man has been described, by NZ On Screen, as “the missing link between 1970s musical legends Blerta, and the burgeoning of Blerta trumpeter Geoff Murphy as a director whose talents knew few bounds.”

Blerta’s colourful, energetic score is a fundamental element of the zany tale of West Coast pioneer con men. The music effortlessly finds the sweet spot somewhere between experimental, accessible, and comedic.

The band’s second and final album, released in 1976, was also called Wild Man and featured music from the Television One series Blerta out of which the film originally sprung.

A director/composer dream team

David Blyth’s controversial Angel Mine (1978) was another film born out of New Zealand’s small but potent underground filmmaking scene of the 70s. It is one of just a handful of New Zealand experimental feature films to win mainstream release.

Similar obsessions and influences that Blyth explored in his previous short, Circadian Rhythms, were also channelled into Angel Mine, his low-budget first feature. It is an explicit, experimental psychodrama about marriage exploring, as NZ On Screen says, “ideas of consumerism, sexuality, the media, and taboo-breaking”.

Use of music is incredibly important to Blyth and for Angel Mine he teamed up with composer Mark Nicholas. The subversive subject matter and unique aesthetic of the film – part punk, part Luis Buñuel-style surrealism – demanded a special kind of soundtrack. Nicholas delivered a constantly shifting, often dreamlike score which sits seamlessly alongside contributions from New Zealand bands Suburban Reptiles and Charisma.

The way Angel Mine’s score flicks between music for classical instruments, pop-oriented instruments and solo piano contributes much to the film’s mercurial atmospheres and moods.

The piano cues, played by Peter Kerin, make up a large part of the score, from the glittering liquid layers in the surreal opening sequence, to wallpaper music and laid-back lounge for TV ad-like fantasy sequences, and percussive prepared piano, fed through wobbly modulation effects when things get darker. Although the piano music often enters the realm of tongue-in-cheek parody, it is often also genuinely beautiful.

Orchestral parts of the score are played by the Auckland Youth Orchestra. Many members wouldn’t have been old enough to even see the film, with its R18 rating.

No New Zealand film before Angel Mine had caused so much controversy and on its release the Censor’s certificate came with the additional warning “contains punk cult material”. Angel Mine became the first of many feature film collaborations on which David Blyth and Mark Nicholas worked their magic. It was the first film to be funded by the newly established New Zealand Film Commission. This new source of funding created many more opportunities for New Zealand filmmakers and composers into the 1980s and beyond.

--

Read more: Film Music Aotearoa, part 1: The 1930s-1960s

Read more: Film Music Aotearoa, part 2: The Early 80s

Read more: Film Music Aotearoa, part 4: The Late 80s

Read more: New Zealand popular music at the movies – 1964 to 2014

--

Ryan Smith is a Wellington-based freelance writer and composer whose articles and radio features have largely focused on music, including film scores. By day he produces Sound Lounge for RNZ Concert (a contemporary classical/experimental music show with an emphasis on Aotearoa’s composers and performers) and presents ambient music show, New Music Dreams.

--

Bibliography

New Zealand Film Music in Focus, Riette Ferreira, University of Auckland thesis, 2012

New Zealand Film: An Illustrated History, edited by Diane Pivac with Frank Stark and Lawrence McDonald, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2011

New Zealand Film 1912-1996, Helen Martin and Sam Edwards, Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1997.

A History of The New Zealand Fiction Feature Film, Bruce Babington, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2007.

[The impact of Sleeping Dogs], Jonathan Dowling, Evening Post, 27 February 1988

Also see the AudioCulture page New Zealand popular music at the movies – 1964 to 2014