It’s a rare and oddly disturbing case of collective amnesia. During the middle part of the 1970s, John Hanlon was as much a part of the popular-cultural scenery as the annual telethon or the Goodnight Kiwi, but for some 40 years on, few remembered him. It was as if John Hanlon never happened, although in more recent times we have rediscovered this seminal and very influential songwriter.

We never were good at documenting, discussing, archiving and writing about and remembering figures from our pantheon of pop. And of course, that’s partly what AudioCulture is all about: redressing this lamentable situation. But John Hanlon is an extreme example, his records were not for many years available or re-released after that move to Australia, and his name and songs were left off those interminable lists and compilations of great New Zealand treasures.

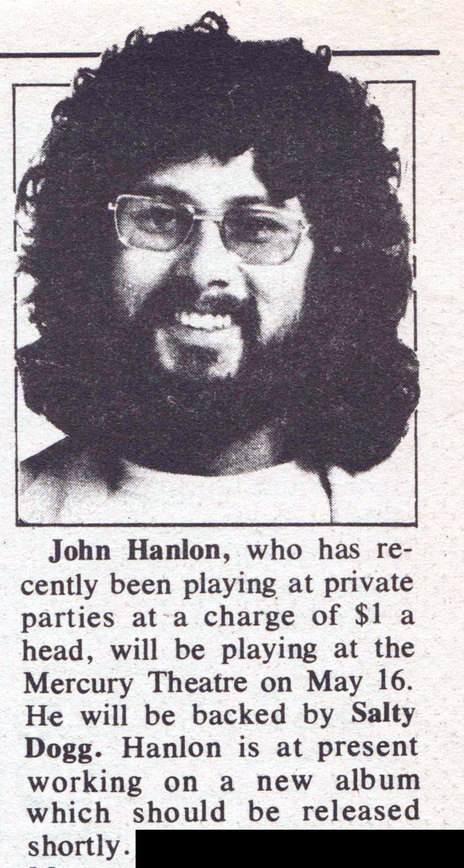

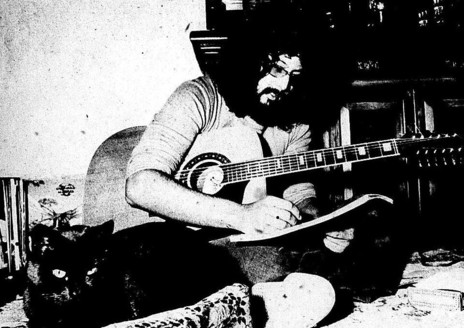

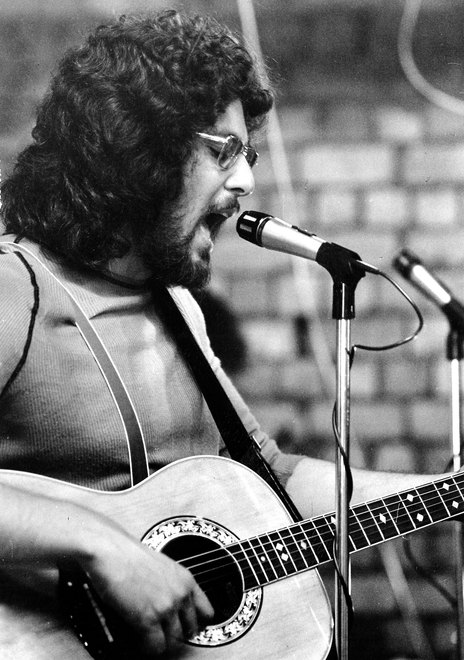

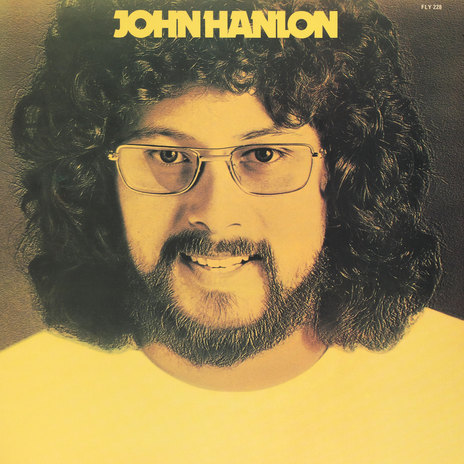

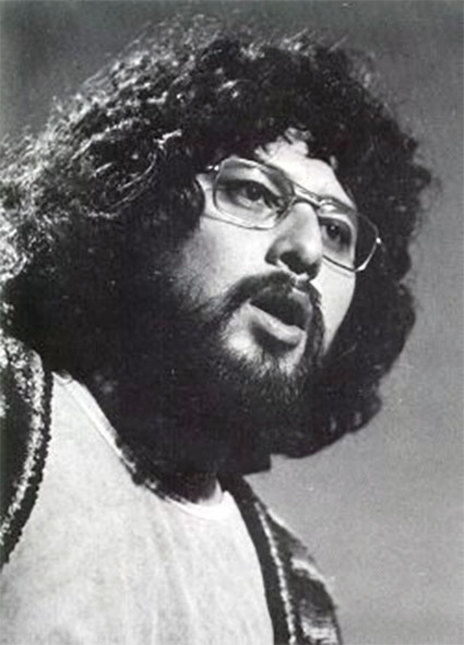

When I meet John Hanlon for an epic interview in an alcove at an Auckland café, the amnesia is reinforced. He looks nothing like the hairy John Hanlon that sang and strummed his way through the 1970s. Gone are the curly mop, the carefully cultivated beard and moustache, and those trademark “square eye” glasses, replaced with a bright-eyed, clean-shaven, smart and surprisingly youthful 64-year-old. He could have been an imposter, except for the razor-sharp memory and detailed reminiscences, dotted with expletives and a refreshing candour.

Clearly, walking away from NZ’s claustrophobic music scene when he did and making a killing in advertising saved him from a much worse fate: the damaging toll on health and sanity so many of our legacy musicians have faced through years of living on the breadline.

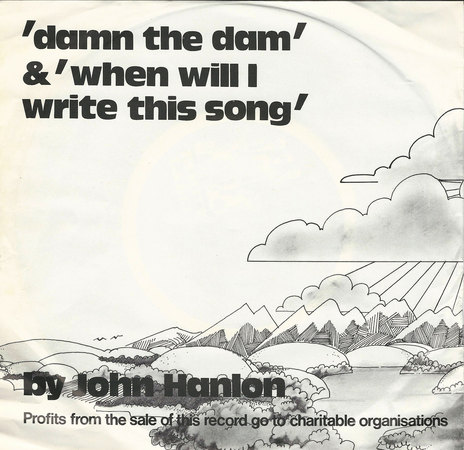

Later, when I listen to the just-released After The Dam Broke, the first authorised reissue of Hanlon’s hits, my amnesia retreats, and I find myself humming along to songs I haven’t heard since the mid-1970s. Even more amazingly, the second disc of later, lesser-known material (some previously unreleased, others released independently in Australia) show a similar propensity with words that hook you and melodies that stick like superglue. And most of it is effortlessly better than the maddeningly catchy jingle that everyone remembers, ‘Damn The Dam’, with songs that could easily have found homes on records by internationally recognised mainstream singer-songwriters such as John Denver or Neil Diamond or Gordon Lightfoot, Jackson Browne or even early Tom Waits.

Born in Malaysia of a New Zealand dad and a Chinese mum, Hanlon was a self-confessed boarding school kid. “I came to New Zealand when I was three months old, went away when I was four, came back when I was eight, went away when I was 10 and came back when I was 15,” says Hanlon. “So I went back and forth, and spent three years in a boarding school in Western Australia, didn’t see my parents from one year to the other, and when I came back here I was socially inept and terrified of girls.”

As a shy teen, Hanlon hid away in his bedroom writing songs, but it was years before he revealed to the world what he was toiling away on. “Even years later, when a journalist asked my mum if she knew her son was a songwriter, she rather embarrassingly said ‘Oh no, we used to know that he spent a lot of time in his bedroom doing a lot of jing and jang.’ And I said to my Mum, ‘You have no idea how that could be interpreted!’”

‘Damn The Dam’ became the unofficial anthem of the then nascent environmental movement, and along the way, something of a millstone around Hanlon’s neck.

Like millions of other budding songwriters in the 1960s, Hanlon was inspired by The Beatles, and rather than writing his own songs, started out to learn theirs. “So I decided that I would learn to play Beatles songs, but what I found was that I was both pathologically shy and rather musically inept, and I just couldn’t learn. I just couldn’t. But I found that when I strummed a chord, tunes came out. The reason my songs are all so melodic is because I can’t write music. I just remember the tune.”

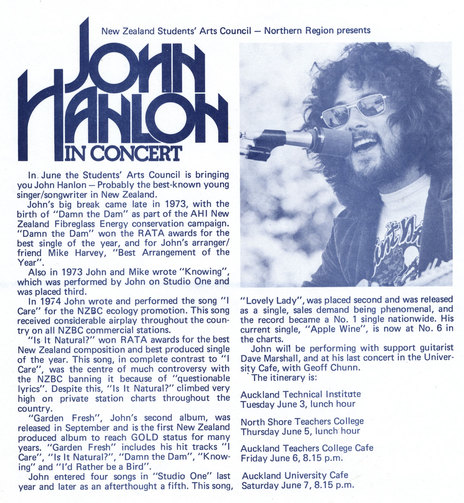

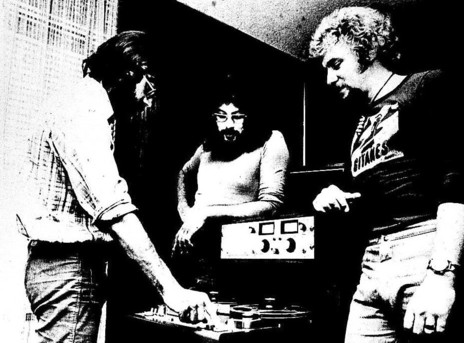

His discovery was more a twist of fate than anything. As a young advertising copywriter, Hanlon freelanced at weekends in Hamilton, and it was there that he was pushed into performing to an informal late-night gathering in 1973. Afterwards, a man who said he owned a recording studio in Auckland approached him. It was Bruce Barton, owner of Mascot studio, who subsequently booked time for Hanlon to get demos of his tunes down on tape.

“At the end of the week of recording we had this huge pancake of tape, about 40 songs – I remember it was four boxes of tape. And on the strength of that I bought a reel-to-reel tape deck so that I could listen to myself, and I seriously thought that was [the beginning and end of] my recording career.”

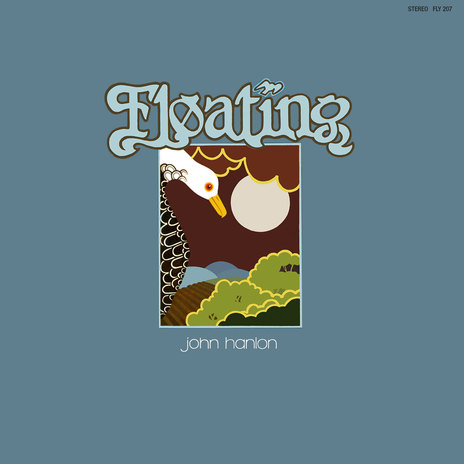

Except that a few months later, he got a call from Tim Murdoch, later of WEA Records, who at this point ran the Family Records label for Pye New Zealand. Murdoch signed Hanlon to an unprecedented three album contract, and recorded his first album Floating, which caused nary a ripple.

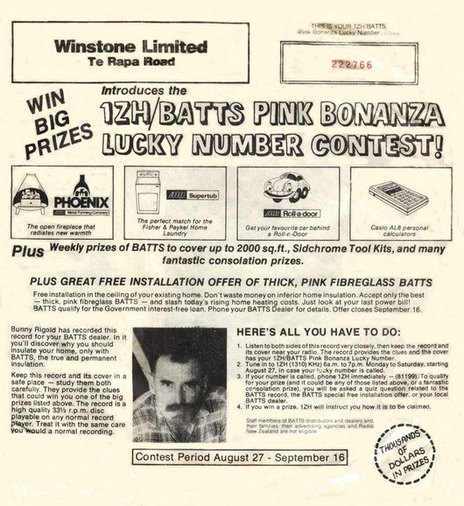

It was ‘Damn The Dam’ a year later – written as a radio jingle for Pink Batts to lobby the government for housing insulation regulations – that proved his big breakthrough. Later adopted by the Save The Manapouri campaign, ‘Damn The Dam’ became the unofficial anthem of the then nascent environmental movement, and along the way, something of a millstone around Hanlon’s neck.

“Where people think of me as being a protest singer and standing up for various things,” says Hanlon, “the reality was that I was just voicing what a lot of people were thinking. But I was never anti-American, or anti-commerce. I was anti-nuclear. People ask me now how I feel about ‘Damn The Dam’ and I say ‘look, you called me on your mobile, and you’re taking notes on your computer, and you’ve probably got an iPod, and we’re actually using far more electricity than we did before. It’s got to come from somewhere. There’s an environmental impact with whatever you do.’”

“My best environmental song was not ‘Damn The Dam’, it was ‘I Care’, which talks about the fact that we talk about shit and we don’t do anything about it. I even allude to what we now know as climate change.”

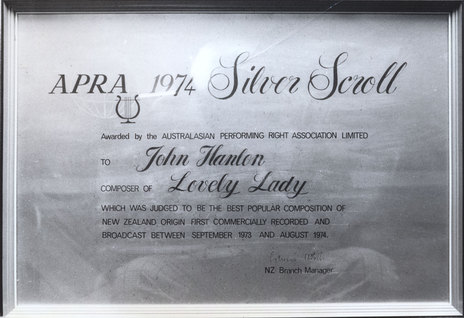

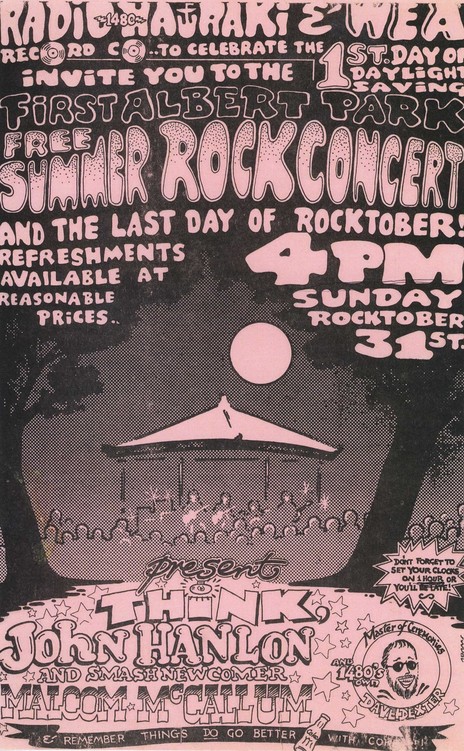

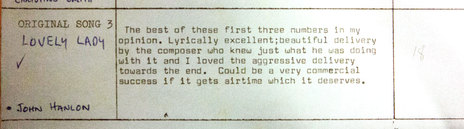

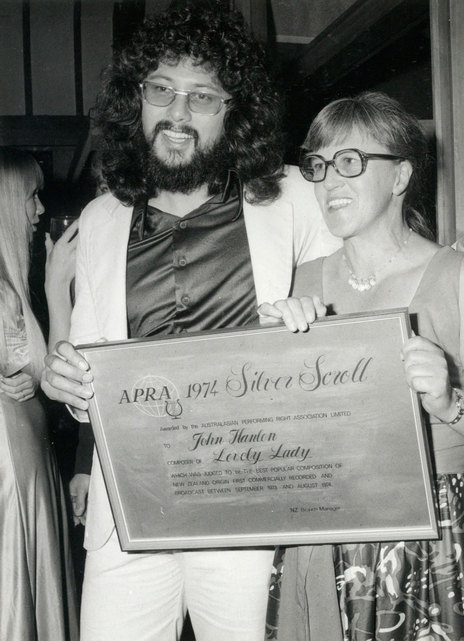

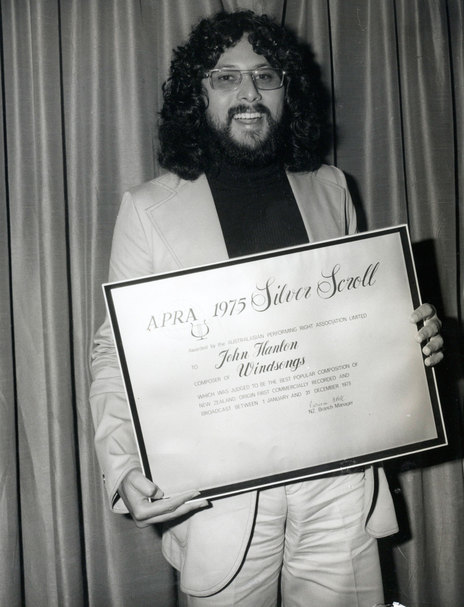

From 1973 to 1976, Hanlon became a household name, with more hits and awards than any other NZ singer-songwriter, winning Songwriter Of The Year three times in a row at the RATA music awards, and APRA Silver Scroll awards for ‘Lovely Lady’ and the terrific progressive-folk of ‘Wind Songs’. During those years, Hanlon’s albums were chart perennials, and in 1975 with ‘Lovely Lady’ he finally cranked up his first and only No.1 smash hit.

Hanlon’s albums were chart perennials, and in 1975 with ‘Lovely Lady’ he finally cranked up his first and only No.1 smash hit.

Yet for all the success, Hanlon struggled working within the bureaucratic and censorial constraints of the government-controlled television and radio monopoly, and two of his songs were banned: ‘Is It Natural?’ for an innocuous reference to a "randy schoolboy", and ‘Crazy Woman’ for its documentarian description of a drunk prostitute attempting to solicit a priest. In real life, she said, “You could do with a root!” In Hanlon’s inoffensive song, “she offered her services to a Catholic priest, he blushed and walked away.”

From the start, his relationship with the powers that be in the entertainment department of state television was rocky.

“I ended up being very grumpy because there was only one TV channel, and I could only go on TV if I agreed to sing and dance. Do I look like a singing and dancing guy? How do you sing and dance to ‘Damn The Dam’? I pissed off (influential producer) Kevan Moore because I wanted to sit on a stool to sing my song. I was terrified to even be there. If you upset them you were gone, and I’m trying to be a songwriter in that environment. But you were expected to toe the line, and I’m just not a toe the line kind of guy.”

The claustrophobia was reinforced when he found out that his attempts to break into international markets were being sabotaged by his own record company.

“I’m getting offers from all around the world. The head of PolyGram A&R came to see me in Ireland. ‘We’re going to make you famous, blah-de-blah’. But my record company owned my contract.”

Hanlon’s record company, Pye, wanted a bigger slice of the pie than anyone was willing to pay. “And of course the international record companies said ‘get stuffed!’”

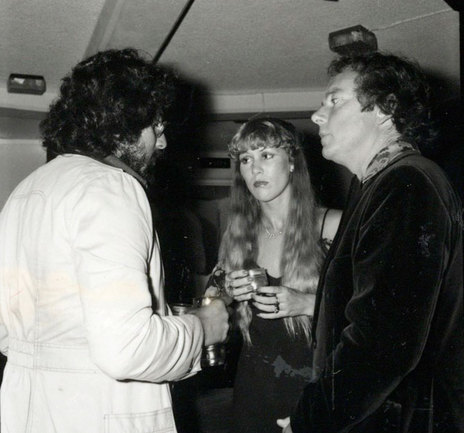

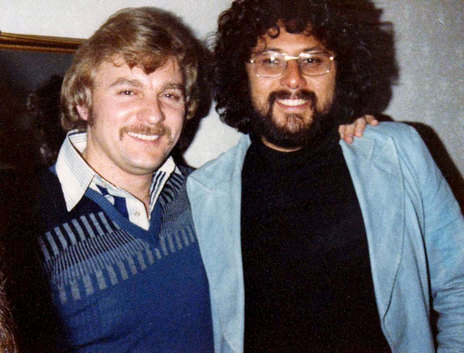

His friends on the scene in Auckland at the time included members of Hello Sailor and The Human Instinct, while rock and roll trouper Tommy Adderley proved something of a mentor. But in a way, these personal/professional associations just proved a point: “I was doing a different thing.” While Hanlon was a huge fan of heavy rock bands like Cream, the songs that came out of his mouth when he sang in that instantly identifiable, Robin Gibb vibrato with a layer of sandpaper voice were closer in spirit to one of his other big influences, Donovan. The inevitability of being one of a few heart-on-sleeve singer-songwriter types in NZ was a sense of separation.

And as he became more successful, Hanlon also felt like a hit machine spewing out the same songs night after night.

“My audience changed. I’d gone from this really interesting, alert audience, to people who came to hear the hits and see the guy. And I wasn’t that guy. There was of course a backstory, which was that the woman I loved, the woman I was now married to, hated this whole thing of we could never go out anywhere.”

Originally, the plan was to temporarily step back into his advertising career, and keep chipping away at the songwriting. He never stopped writing new songs, occasionally recording them through the 1980s and 1990s, but by then his stellar career in advertising had taken over, and in Sydney, he was in a much more creatively tolerant arena than the one he had experienced in New Zealand.

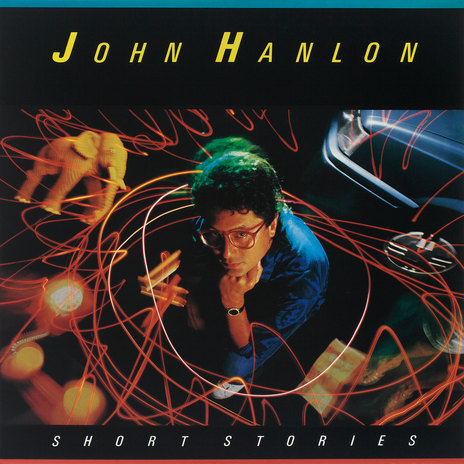

After knocking it on the head, he released just one album in the next decade, Short Stories (1988), hilariously made available only on that then-doomed format, vinyl, just as compact discs had become the dominant medium. Sadly, quality songs were swamped by a typically artificial, tinny 1980s production, and his dulcet tones were hidden in the mix. Few New Zealanders heard it.

Hanlon has self-released several new albums in the past five years, since his official retirement from the halcyon world of advertising. Sampled on the second disc of the career-spanning compilation, After The Dam Broke, these songs are as strong as any from the 1970s, and just as memorable, although the voice has now taken on an almost Tom Waits gruffness with the passing of years. After The Dam Broke also disinters some real finds from Hanlon’s NZ years.

“Some lady from Warner wrote to me saying ‘I’m delighted to tell you that we’ve found the master tapes’. Even better, the guy that rescued them found two songs that were never released – that couldn’t fit on the original vinyl.”

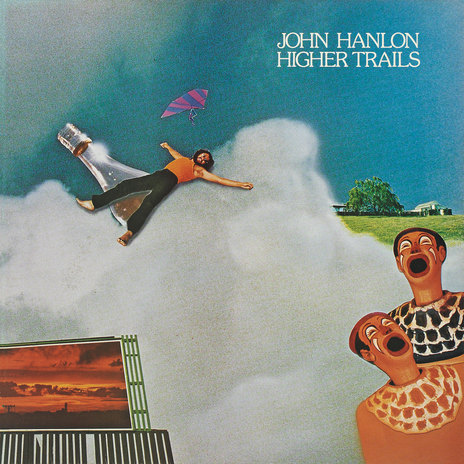

Hanlon says that when listening through the master tapes, he realised that his hit album Higher Trails “is probably as good a production as anything in the world at the time.” And he’s right – it’s a gorgeous example of mainstream singer-songwriting matched to expert arrangements and the very best session players. He worked with the likes of arranger/producers Mike Harvey and Bruce Lynch, and musicians like Martin Winch, Dave Marshall, Billy Kristian, Frank Gibson Jr, Red McKelvie, Dave MacRae and many other local notables.

And then there’s Hanlon’s last and chronically overlooked NZ album Use Your Eyes, with its sparse but utterly gorgeous songs. “My last album is very quiet, there’s a lot of guitar playing and only one other instrument. Beautifully produced but very sparse. I was sitting up at Stebbings with the original producer and engineer and they cried. It was great to hear the stuff.”

Hanlon says that he hopes the remastered double disc compilation will redress the neglect he’s faced in NZ over the years. “If people listen and go away and think ‘I don’t like his music’, then there’s nothing I can do about it. But I think what will definitely come out of it is that I’m a good songwriter. Whether you like me or not, I haven’t finished yet.”

–

In 2014 John Hanlon moved back to New Zealand where he continues to write and record. His catalogue is now widely available.