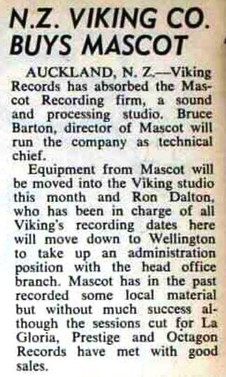

The debut single from Terry Dean and the Nitebeats, backed with Your Mamma's Outta Town, released on Bruce Barton's Mascot label in 1964

It was never Auckland’s top-ranking recording studio, its equipment was almost always dated and throughout most of its quarter-century lifespan its sparse surroundings were chilly in winter and sweltering in summer. But Mascot Recording Studios is fondly remembered by most musicians who passed through its doors.

Drummer Bruce King remembers it clearly. “There was a concrete floor, no carpet, no sound baffling. I’d have my shirt off, sweating, although they eventually put in a fibreglass drum booth and a fan in the roof. The curtains were mismatched and the audio screens were on wobbly wheels but you didn’t have to worry about knocking things over, you didn’t have Margaret Stebbing emptying ashtrays in the middle of a session. It felt like home, really.”

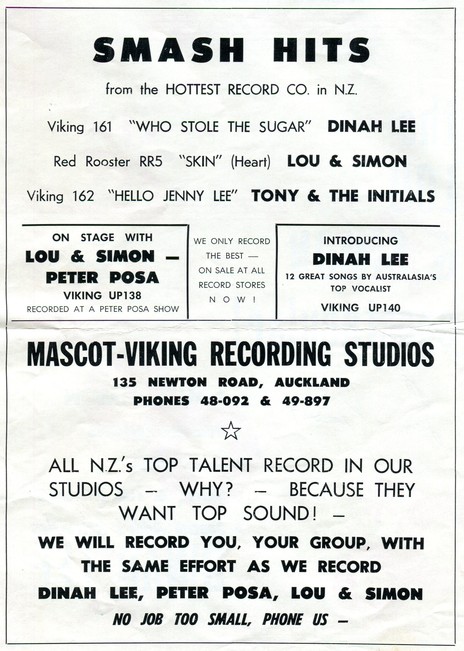

Advertisement for Viking Records and Mascot Recording Studio, from the 1961 Showtime Spectacular tour programme. - Chris Bourke collection

The beginnings of the Mascot Recording Studio can be traced to Bruce Barton’s Auckland Wireless Services, housed at the Pacific Building on the corner of Auckland’s Queen and Wellesley Streets. The site had already played a large role in the development of New Zealand’s recording history – brothers Eldred and Phil Stebbing built their first studio on the premises in 1950, selling it to former Tanza employees Fred Green and Tony Hall in 1953; it was here where Johnny Devlin made most of his early recordings for Prestige Records.

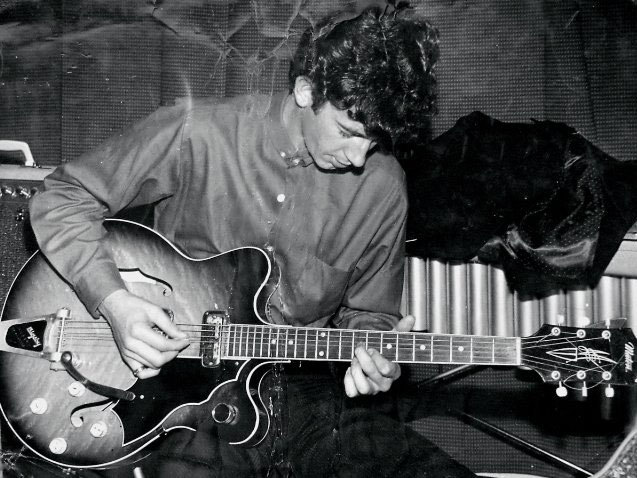

Errol Timbers recording in the Mascot Studios, Pacific Building (now demolished) on the corner of Queen and Wellesley Streets, Auckland

Radio engineer and recording enthusiast Bruce Barton began leasing the studio from Green and Hall in 1959, recording Vince Callaher, Ricky May, Kahu Pineaha, Clyde Scott, The Sheratons and Terry Dean and The Nitebeats, later rebranding the operation as Mascot Recording Studio and in 1962 launching his own Mascot record label, distributed by Viking Records. Among the early acts released on Mascot were folk trio The Convairs, Terry Dean and the Nitebeats, the Fenders (from Hamilton), New Plymouth duo The Lambert Twins, and female pop singers The Kittens.

An early release on the Mascot label: New Plymouth vocal duo The Lambert Twins, backed by The Rexettes, 1962

The Mascot equipment was patchy at best – in 1960, following a fire at Radio 1ZA’s studio, Barton purchased the fire-damaged equipment and although not ideally suited to the recording process, this equipment served Mascot throughout the decade.

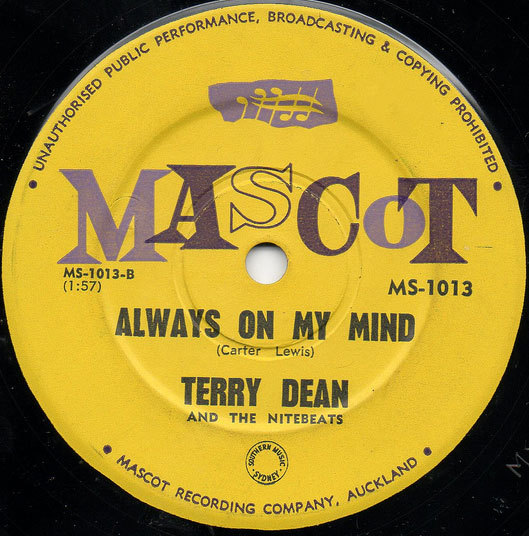

In 1963 Mascot had a brief spell at the Dilworth Building at the bottom of Queen Street before Barton accepted an offer from Viking Records’ Ron Dalton to install the equipment at the Viking Studio on Newton Road. In February 1964, Viking Records bought he Mascot Recording firm, retaining Barton as technical chief.

Billboard magazine announces Viking has bought Mascot studio, 9 May 1964

Over the next two years the Viking Studio produced some of the era’s most enduring recordings, mostly produced by Dalton and engineered by Barton. Max Merritt and The Meteors was the house band and recorded artists included the Meteors, Tommy Adderley, Bill & Boyd, Dinah Lee and Peter Posa. When the Meteors crossed the Tasman at the end of 1964, Jimmie Sloggett was retained as musical director, producing The Keil Isles, Ray Columbus and others.

When Viking closed the studio in 1966 Barton moved his equipment to the nearby Eden Terrace premises. 34 Charlotte Street, leased and later purchased by Barton, served as Mascot Recording Studio through to its closure in 1991. The building also housed a sister company, Barton Sound Systems; although ownership has changed twice since, the company name still survives.

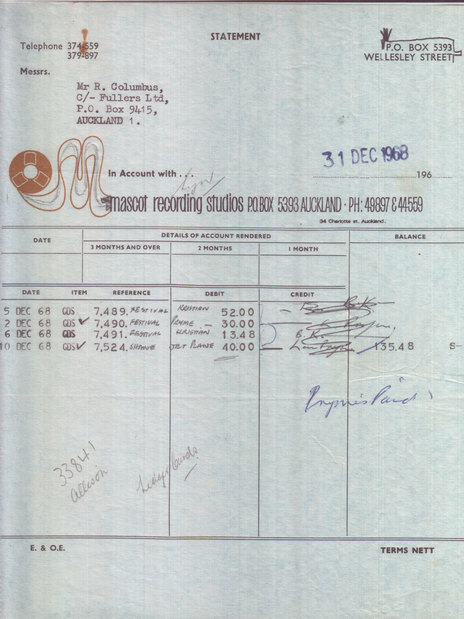

A 1968 invoice for recording from Mascot Studios. Each of these amounts represents a single, recorded in one day. - Phil Warren collection

In 1968 Barton recruited engineer Dave Ormrod, who later acquired the PA company. “I helped build the studio for a twenty percent share,” Ormrod remembers. “It was just a shed, a workshop built by a plumber, a stinking hot place. We didn’t have the funds to go multi-track so it was all one-take, one mistake and we’d have to redo the whole number again, which pissed the musicians off.”

Despite its sub-standard equipment, Mascot proved to be a popular studio. Ray Columbus, Allison Durbin, Sandy Edmonds and The Chicks recorded there; the esteemed Jimmie Sloggett was on call as musical arranger and saxophonist, and backing musicians might include Bob Paris and Billy Kristian. “I was in the studio so much I kept my kit there permanently,” drummer Bruce King remembers.

In 1970 the NZBC launched a new weekly pop music television show, Happen Inn. In a bid to curtail costs, it was decided that the pre-recorded tracks should be produced outside the NZBC’s limited Auckland facilities. Mascot got the contract and throughout the early-mid 1970s the studio survived with its television work.

Larry Elliott spent two years from 1970 to 1972 as studio engineer: “Mascot was always laid back, not the best gear in town but good people, always happy and helpful, a good atmosphere, a pleasant place to be. It was Happen Inn during the week and other recording sessions some evenings and most weekends. Human Instinct’s Pins In It and Larry Morris’ 5.55am are two albums that I recall. There was also a lot of jingles work.”

Gary Potts, who replaced Elliot in 1972, says, “When I arrived there were two studios, the main production studio and the smaller studio set aside for jingles and commercials. Television work carried the studio. On Monday we recorded the rhythm section and strings. On Tuesday I worked on rough mixes for vocal and rehearsal tapes. Wednesday evening, 7pm to 11pm, we recorded vocals and backing vocals, and on Thursday we mixed down to mono and shipped to the TV people. On weekends we’d record bands – The Rumour and Salty Dogg recorded albums there, and Dragon’s first recordings were at Mascot. On one occasion we carted all the equipment down to His Majesty’s Theatre for a live John Rowles album (1975’s Live Back Home).”

The Dragon recordings were a result of Marc Hunter working a deal with Bruce Barton, pottering around the studio in return for recording time. Bruce King remembers his presence: “He was a tall gangly bloke who didn’t seem to want to do a thing, smoking around the studio, not really hands-on with it.”

By the time of Potts’ arrival, little had changed: “It was all ex-radio equipment, all valve gear, a radio mixer. It wasn’t the most modern gear for the era. Bruce and I patched it up and even later the equipment wasn’t the best around. Eldred was always ahead of the game, the first off the block. The Mascot building was primitive, very few doors had hinges, very basic furniture, and there was unfinished woodwork, no air conditioning, which was punishing in summer. But the musos liked Mascot because of the loose atmosphere; they could relax and unwind without fear of their cigarette ash or having to take their shoes off. At Stebbings the musos had to take their shoes off. Mind you, Stebbings had carpet. And air conditioning.”

One of Mascot’s greatest successes was John Hanlon, famously discovered by Barton after he saw the young singer-songwriter singing at a private party in 1971. Hanlon went on to an illustrious career, becoming a household name.

Sadly, Bruce Barton missed most of it, passing suddenly in 1973. He was one of the most popular figures in NZ music. “We all loved Bruce,” Jimmie Sloggett says, “and we missed him terribly after he died. He was a beautiful man, easy to work with.” Words echoed by Bruce King: “He would chat to everyone, as opposed to Eldred, who rarely said a word even if you were working alongside him. Bruce Barton was such a lovely man, short and chubby, relaxed and friendly, and so supportive to everybody.”

Barton’s widow, Muriel, managed Mascot over the coming years although, increasingly, it was Gary Potts and Dave Ormrod who took care of the nuts and bolts. During Potts’s tenure there was a shift in client focus. “The ad agencies would do the rounds for jingles work and all the main studios had phases of being busy but it became increasingly competitive so it was decided to concentrate on the television work, hiring the studios at the weekends for bands at a very competitive rate.”

Happen Inn finished in 1973 but the recordings for Sing!, a strictly middle-of-the-road television series, were all produced at Mascot. Musical director for both programmes was Bernie Allen. Potts says, “Whenever Bernie introduced me, he’d say, ‘Gary and I spend more time together than we do with our respective wives!’ Which was actually true. I left in 1976; after three years of working 50-60 hours a week, I was exhausted and needed a break.”

At the end of 1976, in further attempts at budget control, the newly-branded Television New Zealand pulled the plug on outside contracts. Mascot, having already turned its back on jingles, now had no television assignments and its 8-track studio couldn’t compete with Stebbing’s 16-track facilities across town. There were commercial recordings (notably, Living Force’s self-titled album on Atlantic, and Larry Morris’ Reputation Don’t Matter Anymore, on Parlophone) but Mascot was mostly used by bands as a demo studio.

In 1978, during a recording session, Larry Morris and Hugh Lynn were told by Muriel Barton that the studio might be available for purchase. A deal was done, payments to be drip-fed, and final ownership was still to be determined when Lynn and Morris acrimoniously ended their friendship and business arrangement. Hugh Lynn was to, if not exactly steer the ship, dictate Mascot policy in the coming years.

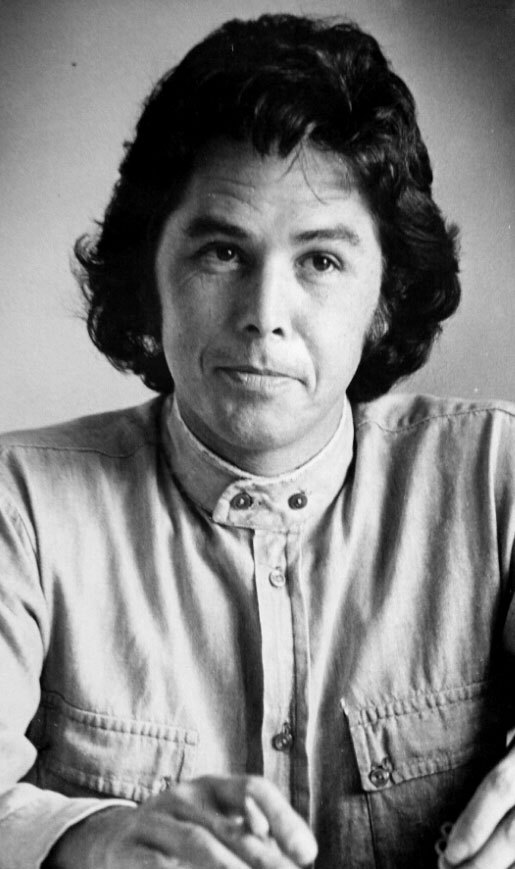

Hugh Lynn in the mid-70s

While all of the above had been going down, this growth of an industry, Hugh Lynn had been playing his own part, and in his own way. He’d had an involvement with entertainment for his entire life: the son of a renowned dance teacher, Da Katipa, and a dancer of note himself, he had given rock’n’roll demonstrations at the Auckland Town Hall, appeared on C’mon, introduced the bands at The Top 20, briefly managed Max Merritt & The Meteors and The La De Da’s, and owned and co-owned Auckland nightclubs. Since 1975 he had been British promoter Paul Dainty’s New Zealand agent, following failed tenures by Phil Warren and Stewart Macpherson.

There were other business interests, other associations – health studios, T-shirt stores, the country’s largest security company, Eden Security. He drove flash fast cars and rode big bikes, hung out with the Hells Angels and studied martial arts.

Brent Hayward humorously tells of his experience at Mascot Studios in 1980. “Gerard [Carr] was unhappy because I said, ‘bro, we haven’t actually got the money.’ He said, ‘Don’t you know this is Hugh Lynn’s place? He’ll want to bust someone’s legs.”

Whatever the reputation and perception of Hugh Lynn, he was about to go through some radical lifestyle changes. The Larry Morris-Hugh Lynn partnership ended badly but for a while, in lieu of any ad agency jobs, Mascot served as a base for Shotgun, Morris’ all-star band. A single, ‘Taste of the Devil’, came out of it but little else before the split in February 1980.

Lynn says, “I had little understanding about the recording process so I left that to Doug Jane, who kept the studio running, and we had people passing through like [engineers] Victor Grbic and Gerard Carr and Phil Yule. Bands sent me demos on a pretty consistent basis. I always felt that I had a feel for a song’s hit potential, I mean back in the Top 20 days, and I enjoyed that side of it.”

Lynn had inherited Doug Jane, whose Mascot connection went back two years, and it was Jane who adapted and modified the existing equipment and installed the 16-track equipment. No sooner had the upgrade been completed than Stebbings announced the arrival of their 24-track equipment.

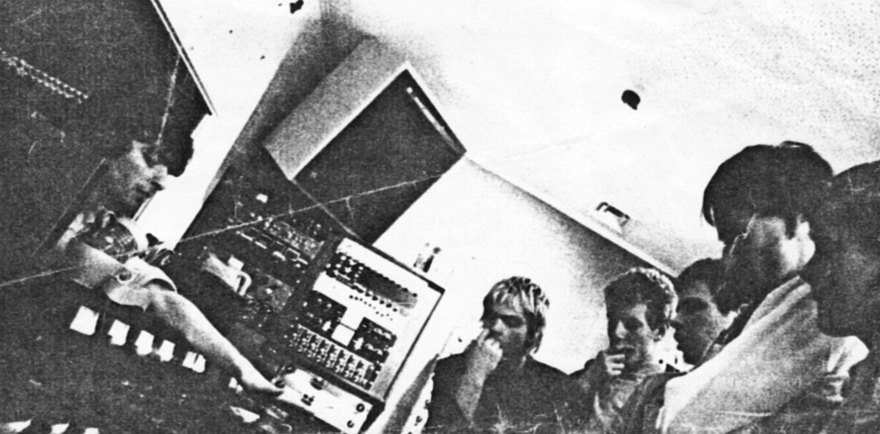

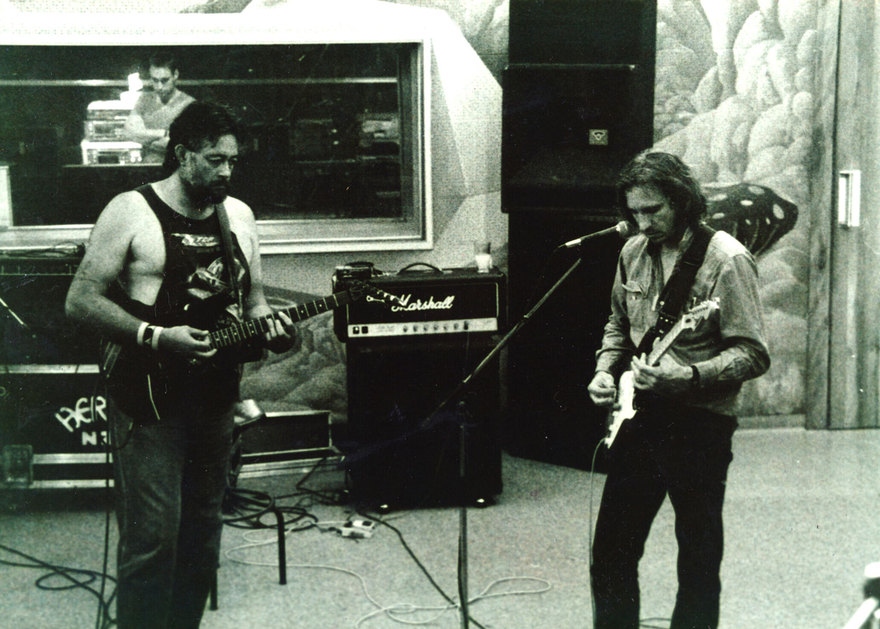

Mascot Studios, May 1980 - Steve Crane, Chris Orange, Karel Van Bergen, Simon Alexander, Jed Town, unknown. - Photo by Jonathan Tidball

By 1981 the competition in Auckland for those advertising agency assignments had stiffened – Harlequin and Mandrill Studios were also in the mix – and Mascot didn’t get a look in. It did, however, become the studio of choice for many of the new wave bands – during a return visit to New Zealand, Dave Russell produced demos of The Scavengers and Toy Love; The Swingers’ first recordings were made at Mascot; The Spelling Mistakes’ ‘Feel So Good’ (produced by Fane Flaws) was a Top 40 hit and helped launch Propeller Records; Penknife Glides’ ‘Laugh or Cry’ / ‘Taking The Weight Off’ (produced by Alastair Riddell) was the first release on Lynn’s fledgling label, Warrior Records. But Mascot Studios largely served as a base for Herbs.

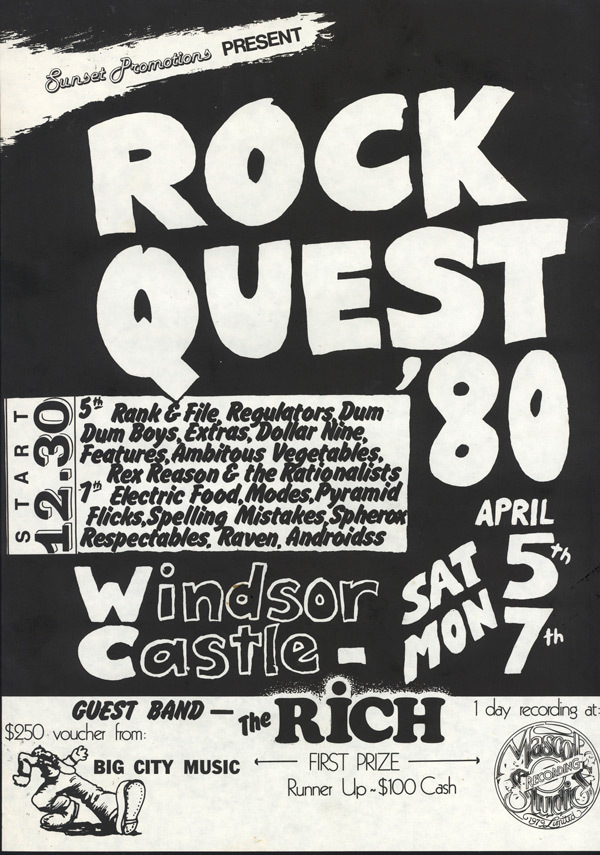

The April 1980 Rock Quest '80. The Spelling Mistakes won and used the recording time at Mascot to record their debut single Feel So Good. - Simon Grigg collection

Bruce King, for whom Mascot had long served as a second home, says, “Once Hugh got in there it became Herbs’ studio, a very ethnic cartel for the whānau.” Lynn concurs: “There was a perception that it was Herbs’ headquarters and I suppose it was. Guys from the ad agencies would come for a meeting and get freaked out, all these big Māori guys hanging around the foyer; they thought it was a gang in residence.”

Herbs had come to Lynn’s attention through their manager, Will ‘Ilolahia, a founder-member of the Polynesian Panthers, who did much to politicise Hugh Lynn. Herbs themselves, who Lynn was soon managing, did the rest. By his admission, Hugh Lynn became a “born again Māori” and this change was to have a profound effect on Māori acts throughout the 1980s, Mascot recording Billy T James, Diatribe, Prince Tui Teka and, above all, Herbs.

In 1983 Billy Karaitiana returned to New Zealand after 10 years overseas. In London he had gained some studio experience, producing demos by Larry Morris, amongst others. Although they’d been acquainted since the 1960s, it was mutual friend Tommy Ferguson who suggested that Karaitiana take the helm at Mascot, to replace departing studio manager Bob Jackson.

“It was 8-track when I arrived,” Karaitiana recalls, “in the process of being upgraded to 16-track. Doug Jane was getting it happening. The equipment was really old, the desk was from previous days. I think Phil Yule loved that desk!”

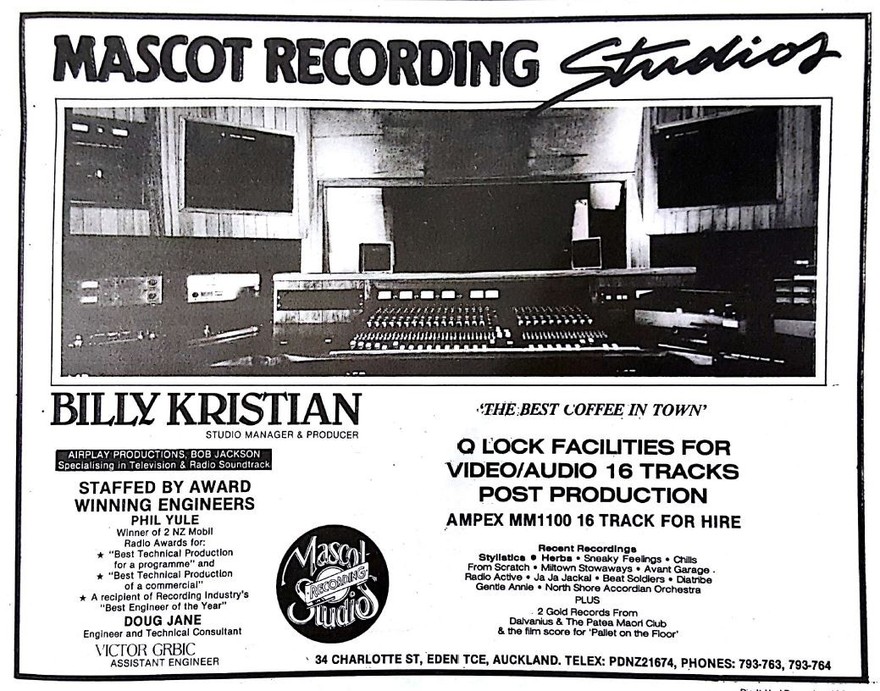

Advertisement for Mascot Recording Studios, December 1984. Among their clients, Herbs, the Patea Maori Club, and the North Shore Accordion Orchestra

Karaitiana was studio manager for five years, producing two Herbs albums, Long Ago and Sensitive To A Smile. He left to start his own home studio, Muscle Music, in 1987. Looking back, Kristian says, “Although I would occasionally work with other bands – like Daggy & The Dickheads, the Lounge Lizards was another, Rotorua band – I looked at Mascot as Herbs’ studio. We were in there almost every day. Herbs needed someone to bring them together, they needed organising. They were big guys, not easy to handle, but gentle guys, all of them. We had a good relationship between us.

“Herbs would put feels together and I would help them find it. Well they’d do it themselves anyway. They’d sit on a riff for half an hour, going through all the feels. I felt lucky to have been able to work with Herbs, and at Mascot, it was a learning curve. It was cheaper than other studios. It was somewhere to go if you had no bucks. It was good for bands.”

Herbs may have taken up most of Karaitiana’s time as studio manager/producer but the engineers who passed through Mascot in the 1980s – Gerard Carr, Steve Crane, Doug Jane, Victor Gbric, Phil Yule – worked with a myriad of acts – from Penknife Glides to The Verlaines. Phil Yule remembers Macot being very popular with “the stage two Flying Nun bands, who’d come out of the bedroom, leaving the 4-track behind to brave it in the 16-track world.” The Chills, Sneaky Feelings, Tall Dwarfs and The Verlaines all recorded at Mascot.

In 1989 a regular presence at the studio was Joe Walsh, the Eagle himself. Walsh had met Lynn and Herbs at a Greenpeace concert and, at WEA Records head Tim Murdoch’s behest, Walsh spent six months in New Zealand, touring with Herbs and producing their third full-length album, Homegrown.

Hugh Lynn says, “Joe needed to get away from the environment he was in, and I think he liked New Zealand and working at Mascot with Herbs because it was like stepping back to his early days. In retrospect, it was the wrong move, his sound wasn’t suitable to what Herbs was about.”

The Joe Walsh/Herbs tour and the ensuing Homegrown album were both financial failures and there were further setbacks, resulting in bankruptcy and the closure of Mascot Recording Studio.

Herbs' Dilworth Karaka with Joe Walsh, Mascot Studios, April 1989 - Photo by Graham Hooper

Looking back, Lynn says, “When we went 16-track, Eldred Stebbing upped the ante with a 24-track studio. The decision to install our own 24-track was premature and I believe that we could have kept the studio going with the 16-track, catering to the Māori music industry and with those acts – the Flying Nun bands, for instance – who didn’t require a state-of-the-art recording facility.”

The Mascot building still stands at 34 Charlotte Street, dwarfed by the high rise buildings surrounding it, housing other businesses with no regard for the history it contains – almost the entire Herbs catalogue but also Allison Durbin’s ‘I Have Loved Me A Man’, John Hanlon’s ‘Damn The Dam’, The Chills’ ‘Doledrums’, The Verlaines’ Doomsday’ ...