Well before the deadly words “mission statement” ever crossed a corporate executive’s lips, New Zealand’s first independent record label made its purpose very clear. The name Tanza stood for “To Assist New Zealand Artists” – and that’s exactly what the label did when it was founded in the late 1940s. New Zealand music was its raison d’être, and to emphasise this, Tanza’s label design featured a tui, one of the country’s most tuneful native birds.

Starting with ‘Blue Smoke’ in June 1949, and finishing with The Keil Isles’ ‘Sea Cruise’ a decade later, Tanza released about 300 two-sided 78s, a couple of dozen 45rpm singles, five EPs and three albums. Well over 1,000 recordings were made in its studio in Wellington and in the Astor studio in Auckland, as well as scores of private recordings and pressings. The music ranged from Hawaiian-style pop to rock’n’roll, taking in country & western, jazz, classical, instrumentals, novelty and sweet vocals along the way.

Tanza was a subsidiary of Radio Corporation of NZ, a publicly owned Wellington manufacturing company founded in 1932 by William Marks, a Russian émigré. As its name implies, Radio Corp made radios and later radiograms, selling them in its own chain of stores around the country, the Columbus Radio Centres, and in other retail outlets. Their showcase product was the Columbus valve radio, housed in moulded veneer walnut cabinets.

When selling gramophones it helps to also sell records to play on them, and the difficulty of getting those records is what led to the creation of Tanza. For the first half of the 20th century the New Zealand record industry was dominated by His Master’s Voice (NZ) Ltd, a subsidiary of the large British firm. In New Zealand HMV had a virtual monopoly with distribution rights to the vast majority of the best UK and US labels. Their discs were imported, from the Northern Hemisphere or – after 1926 – from the HMV/ EMI pressing plant at Homebush, Sydney.

Marks died in October 1946. He never wanted the Columbus Radio Centres to sell anything other than radios, radiograms and their accessories, so with his death the company was able to explore fresh ideas. Executives at Radio Corp – among them, Marks’s son Alex, and the production manager Fred Green – could see the potential and energy of the company. Among the new areas in which they considered diversifying was the idea of making recordings. The clientele would be weddings, parties, race meetings and advertisements. It was advertisements for radio that provided the studio’s income: the agencies wanted pre-recorded ads, rather than having the radio announcers read them out. It is estimated that Tanza made over 4200 advertisments for advertising agencies.

The Columbus Radio Centre in Victoria Ave, Wanganui, 1945

What forced Radio Corp’s hand to enter the record business was HMV, which had its own retail stores selling everything from gramophones to fridges and toasters – as well as records. Radio Corp – which would eventually open 33 Columbus stores around the country – wanted to stock discs alongside their own radiograms. At first, HMV allowed this in only two stores, in the towns without an HMV branch or distributor: Dannevirke and New Plymouth.

Auckland, 1949: musicians who regularly recorded for Tanza, in a 1YA radio studio. From left: Wally Ransom, Mavis Rivers, Nancy Harrie, Mark Kahi and George Campbell.

Once a week in Wellington from 1947 a young Radio Corp employee called John Shears would walk along Wakefield Street to HMV, to collect the box of 78s destined to Dannevirke and New Plymouth. These discs were shipped from the EMI pressing plant in Sydney. In mid-1948 Shears was called into the office of the Alfred Wyness, the formidable managing director of HMV since 1931.

Wyness told him: “There are no records.” At first Shears didn’t understand – was the boat late? No, HMV had decided to refuse to supply Radio Corp with its order of 30 discs each week. “There won’t be any more,” said Wyness.

When Shears got back to Radio Corp and reported what had happened, his boss, Bart Fortune, called in other executives and got Shears to repeat the story. “This was the gauntlet being thrown down,” Shears recalled to me in 2006. “I suspect that’s when the decision was being made that we would press records, not just be a recording studio.”

Green had worked at Radio Corp since 1938 and at the end of the war was the production manager (during the war they had stopped making radios and instead manufactured items for the war effort). He travelled to Britain in 1946 to hire staff and source raw materials. The following year Radio Corp employed Stan Dallas, a 21-year-old sound engineer at 2ZB, to design a studio in an old foundry at 262 Wakefield Street, which backed onto their premises at 80 Courtenay Place.

Dallas designed and built the studio and recording equipment based on the Broadcasting facilities he used in his day job (where he was still employed: he was moonlighting for Radio Corp). For about three months Dallas and the Radio Corp staff experimented with all the techniques needed in the process from recording to manufacture. Once the Bakelite department had finished work and the press had cooled down, they tried pressing discs, getting the temperature and settings right, and then usually trying to press one test disc a night. This went on for about three months.

Green went to Sydney and bought some second-hand record presses; these were shipped to New Zealand as well as dozens of boxes of “biscuit” – rectangular pieces of shellac to use on the presses. “Our early experiments were amazing,” said Dallas. “We had about one hundred 12-inch vinylite advertising discs as a base material. I would make an acetate and Fred [Green] and I would make a copper stamper. We would fit the stamper into a Bakelite press, pre-heat the old advertising disc in an oven, transfer it to the press and reform it to whatever I had recorded.”

Six months after the recording of Blue Smoke, the National Film Unit recreated the occasion for a newsreel to screen in the week the disc was released in June 1949. The trio of white-coated Tanza staff is, from left, John Shears, Tony Hall and Stan Dallas. Leaning over at left, in shirtsleeves, is Bart Fortune, label manager and creator of the name Tanza.

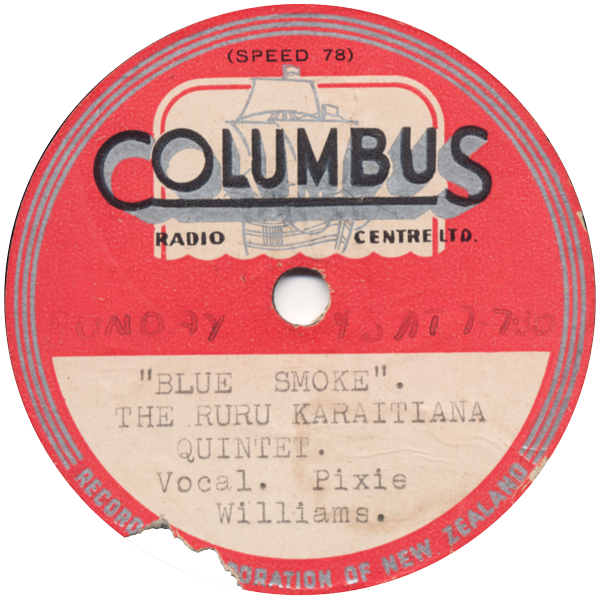

In October 1948 an advertisement appeared in the NZ Listener saying the Columbus Recording Centre was open for business. This was the month in which the “Ruru Karaitiana Quintette” made its famous recording of ‘Blue Smoke’, with Pixie Williams singing accompanied by Jim Carter’s dance band. Williams often spoke of the recording sessions being interrupted by a noisy refrigerator – something that Shears disputes. “I can’t remember that at all,” he says.

“The reason it took some time was (a) the musicians weren’t happy with what they were doing, (b) we were learning how to get the best balance to get what we reckoned was the best sound, and (c) to get the best levels. Because our biggest difficulty in those days was getting sufficient level on to a disc, so it would play back on what were mostly mechanical gramophone players, not electric ones. There are a whole series of technical reasons why it’s difficult to get the level you’re looking for in a pressing.” The first discs actually pressed and released by Radio Corp were Australian recordings on the Tempo label.

The man who had the idea to call the label Tanza was Bart Fortune, sales and promotion manager at Radio Corp, inspired by Joseph Schmidt’s 1948 pop song ‘La Danza’ and adapting it with his strong sense of cultural nationalism.

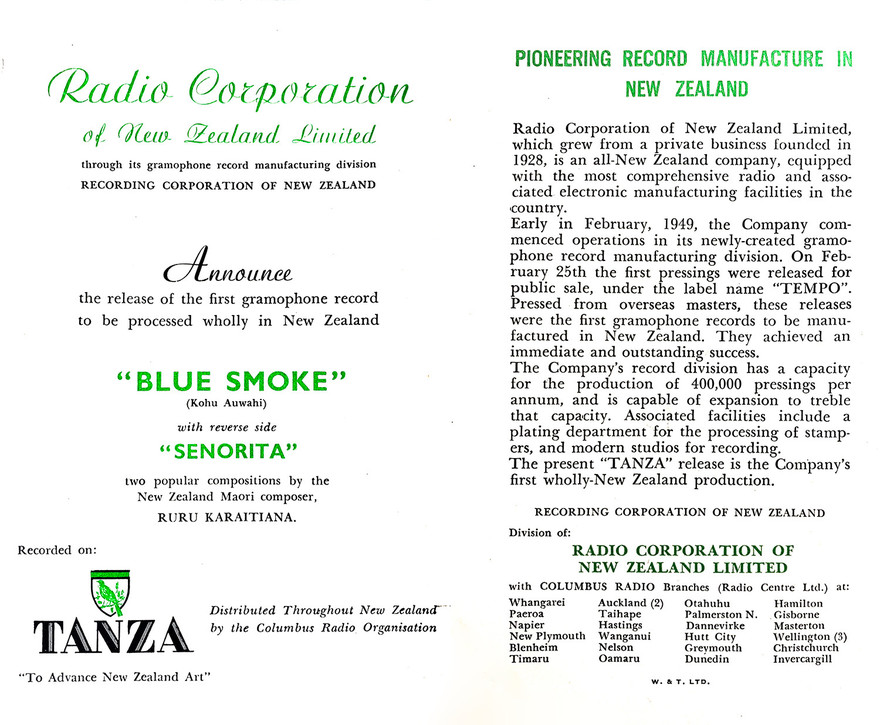

A 1949 brochure that was included with the first pressing of Blue Smoke. It describes the new company - TANZA - and its mission. The brochure defines TANZA as standing for "To Advance New Zealand Art". By 1950, this had become "To Assist New Zealand Artists". - Archive of NZ Music, Alexander Turnbull Library

Inside the 1949 Tanza brochure that came with Blue Smoke, it describes what the coloured record labels on the discs signify. Green is for popular music by New Zealand artists, red for works by New Zealand composers, and blue for New Zealand artists performing works by international artists. - Archive of NZ Music, Alexander Turnbull Library

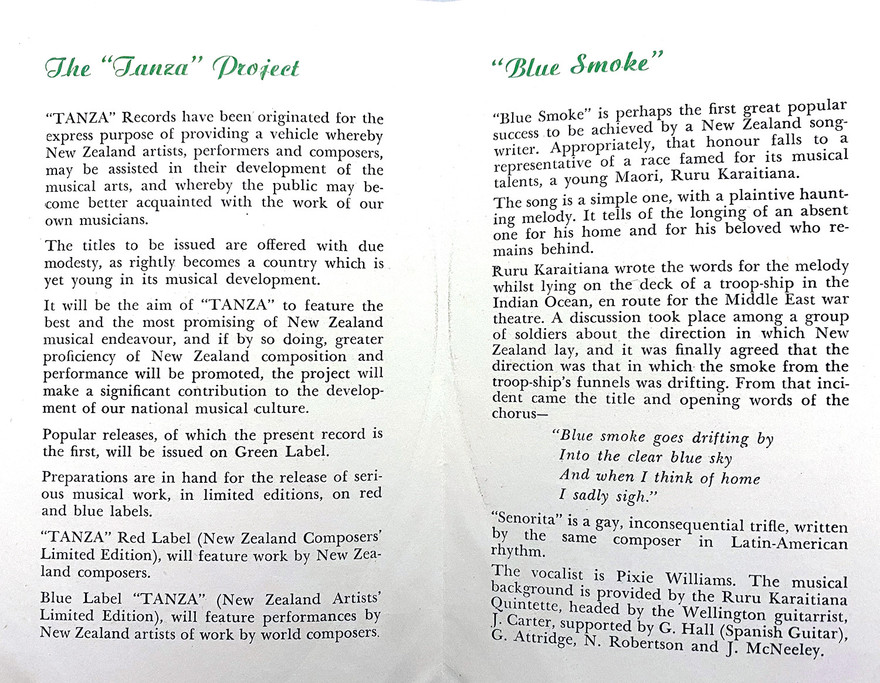

The sheet music to the second Tanza release, Paekakariki by Bill Crowe and His Orchestra

The follow-up to ‘Blue Smoke’, Tanza #2, was another New Zealand original. ‘Paekakariki’ was sung by its composer, Ken Avery, in a style that suggests Noël Coward in the shade of a pohutukawa. The disc is credited to Bill Crowe and His Orchestra – a local dance band that included Jim Carter on guitar. (More entrepreneurial than musical, drummer/ bandleader Crowe kept one tradition of jazz alive through his work managing a long-running Wellington brothel.)

The Tumbleweeds with Tex Morton, Dunedin, 1950. From left: Bill Ditchfield, Tex Morton, Cole Wilson, Sister Dorrie, Nola Hewitt and Colin McCrorie. - Colin McCrorie Collection

An early foray into mobile recording came in 1950, when Tanza bought a Magnacorder tape machine from a US Marine based at the American Embassy. Very new technology, the Magnacorder was far from portable. But it was so precious that when Dallas and Shears travelled by plane to Dunedin to record The Tumbleweeds, they strapped the Magnacorder into a seat of its own. On the way back they taped Christchurch band leader Martin Winiata and his glamorous singer Coral Cummins – using just one microphone. “We were able to get Western Electric cardoid microphones, which did us nicely for a long time,” Dallas told Gordon Spittle in 1992. “They’re still a popular microphone.”

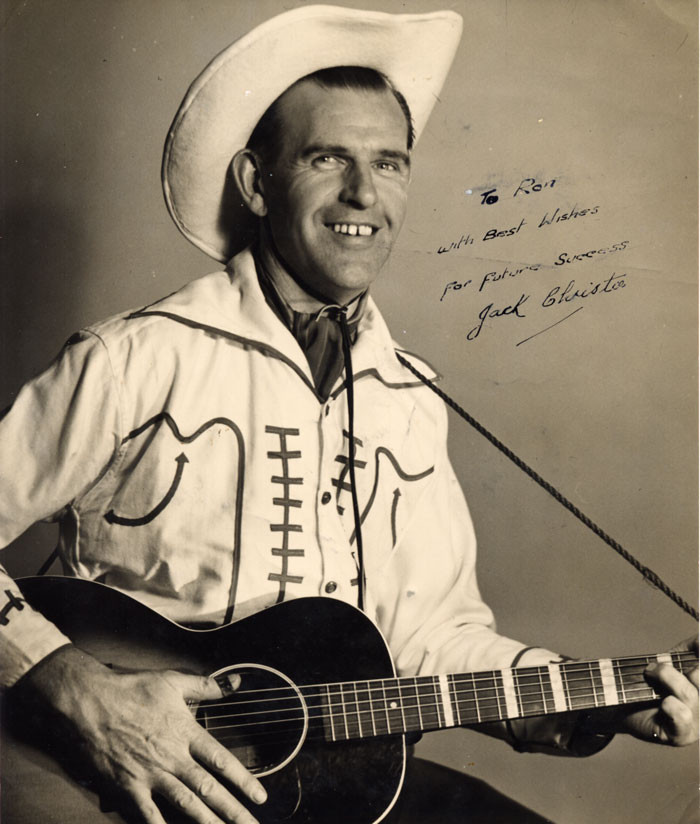

Yodeller Jack Christie released eleven 78s on Tanza between 1950 and 1952 - Ron Haywood collection

The Tumbleweeds discs proved to be the label’s biggest sellers – about 100,000 said Dallas, whereas ‘Blue Smoke’ sold about 50,000. Among the other acts recorded and released by Tanza in its earliest days were Gerry Hall’s Novelty Strings (Hall was the guitarist on ‘Blue Smoke’), and the country yodeller Jack Christie (who at some point worked in the Radio Corp warehouse).

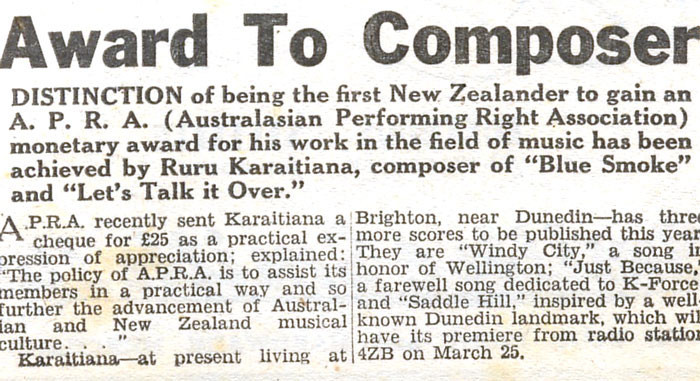

In 1951 APRA paid Ruru Karaitiana £25 for Blue Smoke, the first New Zealander to be thus paid

Dallas was keen to push the boundaries. In 1949, emulating Parlophone’s mobile recordings of Ana Hato in the late 1920s, Dallas travelled to Rotorua and recorded Deane Waretini with Pepo Heretaunga and the Arawa Concert Party. However the quality of the mobile equipment wasn’t good enough, so the singers travelled to the Wellington studio and recorded ‘Po Atarau’ (‘Now is the Hour’) and ‘Hoki Hoki Tonu Mai’. With local recordings, said Dallas, “My neck was on the line every time because I had to make some money for Radio Corp. They weren’t interested in testing.”

Gerry Hall’s Novelty Strings in 1950

An early Tanza recording featured Henry Rudolph’s Harmony Serenaders, with crooner John Hoskins accompanied by a choir of sopranos and a string section led by Alex Lindsay. Other groups included the Tawharau Quintet, a five-part Māori harmony group from Otaki; the Bula Quintette, formed from the crew of a visiting Fijian merchant ship; and the Kiwi Concert Party with a powerful recording of the swing standard ‘Sunshine Cake’. Tanza also recorded brass bands and classical music, including two songs by Douglas Lilburn, ‘A Summer Afternoon’ and ‘Willow Song’ (from his incidental music to Othello), performed by soprano Gabrielle Phillips.

In 1950 Radio Corp secured the rights to press and release Capitol records in New Zealand – one was Nat “King” Cole’s ‘Too Young’, banned by Broadcasting – and the pressing plant staff worked in 12-hour shifts to fulfil the demand before Christmas.

Among the many curiosities in Tanza’s catalogue is 1953’s ‘Misty Moon’, a song composed and performed by George Fraser. By day, Fraser worked at Broadcasting; by night he was an aspirant spy for the Special Branch, studying music at university and joining left-wing groups, staying vigilant about possible pinkos. Eventually, his minder in the spy service told him to “lay off the music”: light pop was “too petit-bourgeois” for someone pretending to be Communist, and could make his comrades suspicious. “Folk songs are okay because they are into that, but not that sentimental American stuff.” While ‘Misty Moon’ received some airplay, its lasting value is that it provides a flipside for ‘Salad Bowl’ – an original by Wellington multi-instrumentalist Bill Hoffmeister, and one of his few recordings.

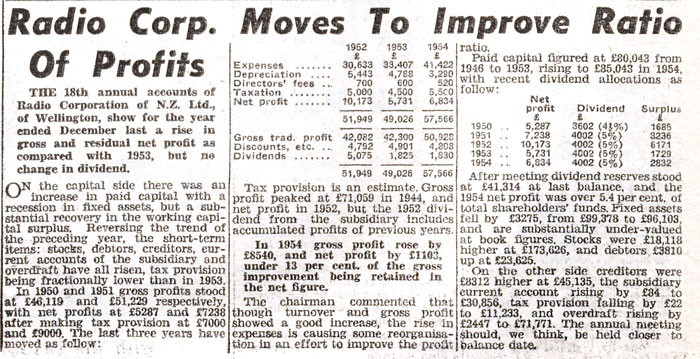

The financial report for Radio Corp. as reported in the New Zealand Truth, August 1955

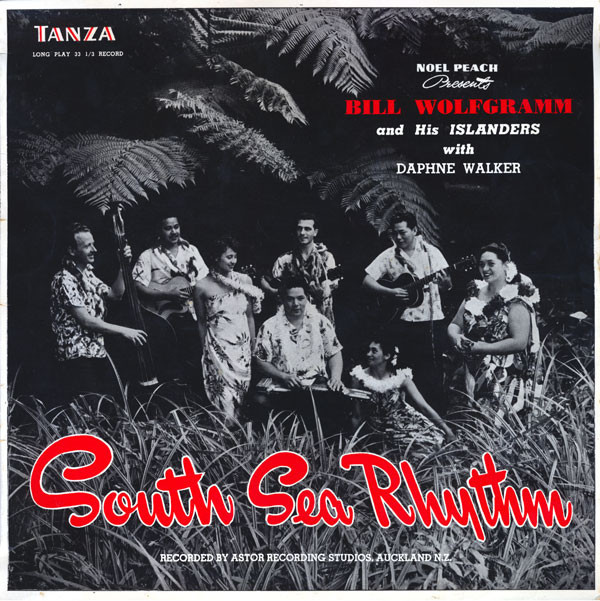

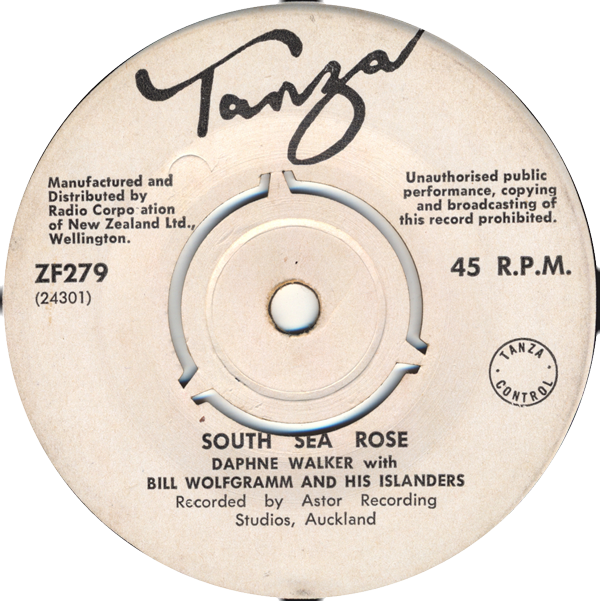

At the same time that the Wellington studio acquired its tape recorder, so did the Auckland engineer Noel Peach, who supplied material to Tanza. These Auckland recordings, made at his Astor studio in Shortland Street, quickly dominated the Tanza catalogue, with acts such as Mavis Rivers, the Astor Dixie Boys, the Knaves, Pat McMinn, Lee Humphreys, Daphne Walker and Nancy Harrie.

Noel and Vida Peach, 1950. The caption says they are testing "apparatus for making phonograph records - the first such firm in Auckland. Opportunities? Lots of them!" - 8 O'Clock, Auckland, 5 August 1950

In 1956, Peach’s recordings with Bill Wolfgramm and His Islanders became New Zealand’s first LP, the 10-inch South Sea Rhythm, released by Tanza.

The 1956 10-inch LP South Sea Rhythm, by Bill Wolfgramm and his Islanders with Daphne Walker (Tanza).

It was at Astor in 1956 that one of Tanza’s biggest hits was recorded, ‘Opo the Crazy Dolphin’: an affectionate novelty song about Opo, the famous friendly dolphin at Opononi Beach. Written by jazz pianist Crombie Murdoch – at the suggestion of Noel Peach – and sung by Pat McMinn, Bill Langford and the Stardusters, the disc had just been recorded when Opo mysteriously died. Unlike record companies of today, Tanza briefly hesitated before releasing the disc, wondering if it was in good taste. Tanza A&R man Murdoch Riley recalled calling Peach and saying “What do we do now?” Peach said, “We’ve spent the money recording it, now let’s put it out and hope for the best.” They sold 10,000 in the first week, all the company could produce. Stan Dallas joked, “If Opo had lived for another bloody week, we would have sold 20,000.”

By 1956, though, Tanza was winding down. This, despite having Bill Haley’s version of ‘Rock Around the Clock’ – to the chagrin of HMV – and also the rights to RCA, just as Elvis Presley was breaking through. Rock’n’roll was too new to be seen as the future money spinner. Radio Corp lost the lucrative Capitol franchise in 1955, and it was Nat “King” Cole himself – a director of the US label – who told Fortune the bad news when he arrived at Whenuapai airport for his concert in Auckland. He then said hello to Fortune’s arch-rival, Alfred Wyness, head of HMV, whose parent company EMI had just bought Capitol.

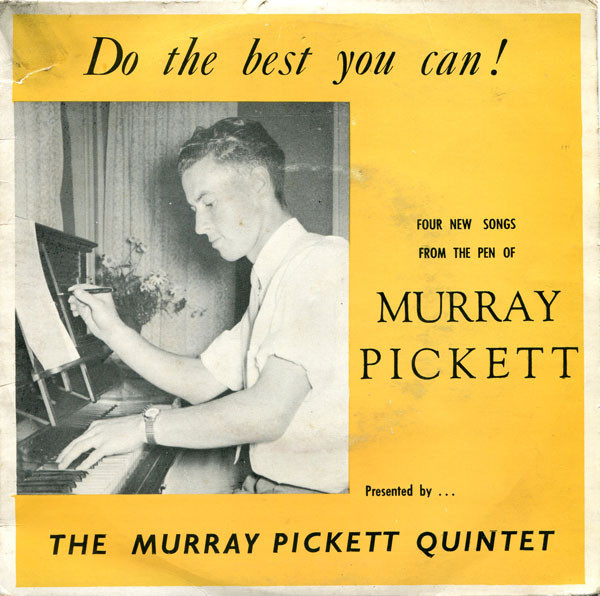

Murray Pickett Quintet's Do The Best You Can was the first 7-inch EP released by Tanza, in 1957

Dallas said there were so many releases coming in from the US, Australia and England, that the company just “could not compete … old Noel Peach was blowing against thunder.” Riley points to poor management at Radio Corp: by this stage there was little commitment to local recording or their pioneering label. “They wanted products for their shops. The number one priority was to sell the radiograms, and with the radiograms you needed something to play on them, that was the idea of the record company. Where the product came from – if it was very popular, very good – but it wasn’t the key point as far as Radio Corp was concerned, it was just a sideline.

“The record side was an adjunct, and a very sensible one really. But they had got into a bit of difficulty with it because of the quality. [Eventually it was determined that Wellington’s water made for inferior pressings during this period.] So much stuff was being sent back to Tanza. My job was really to stir it all up and get it going again, which I think I did. But of course I had this huge advantage of RCA.” The access to RCA releases came through AWA Australia, which had a large shareholding in Radio Corp.

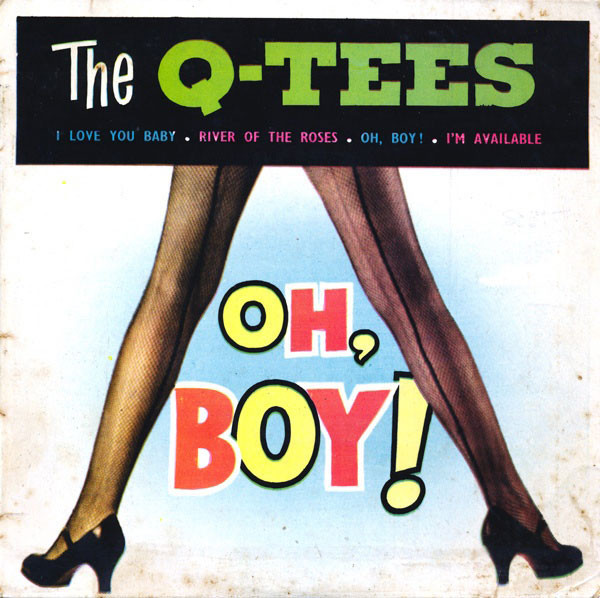

Palmerston North band The Q-Tees 1958 EP on Tanza

The artists Peach recorded in Auckland sold well, but the Tanza management of the mid-1950s insisted on supplying too many copies of releases – local and overseas – to the radio stores around the country. “What disgusted me was this policy of pushing product into shops when they didn’t need that many copies,” recalled Riley. “This was the thing, ‘We’ve pressed that many, and we send them out to the shops, it keeps the presses working’. Of course I was able to divert a bit when RCA came along, I needed the press capacity for those releases.

“There were times between contracts when Radio Corp had practically no product. When I came along the choice was, did I want the RCA or the Columbia agency? And I plumped for RCA which was a good thing because we got Elvis Presley.”

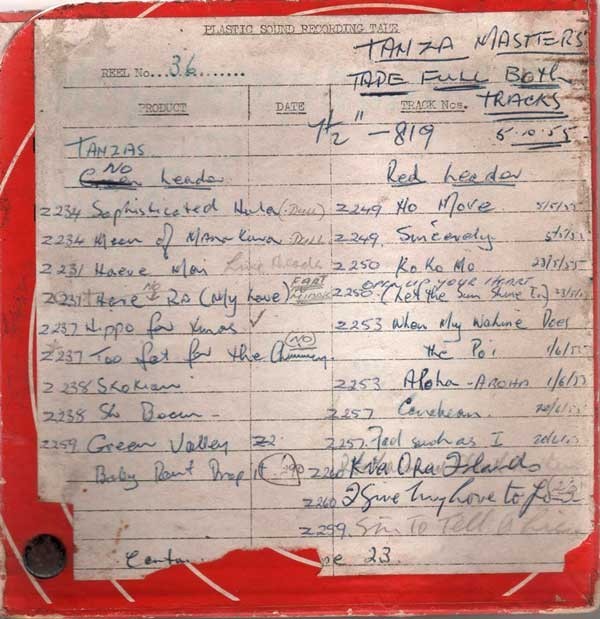

A 1955 Tanza tape masters box - Chris Bourke collection

Riley left out of frustration. “The problem [with Radio Corp] was they had financial difficulties and everything was falling apart as far as the shops were concerned. They were selling radiograms, but the whole administration wasn’t good enough. They weren’t profitable, they weren’t making money. I wasn’t able to develop the RCA label as it should have been. I was restricted because of finances. I could see that I could only do better on my own. And that was a bit of a struggle. I took a job at the Lamphouse.” Riley would soon launch Viking Records, one of New Zealand’s leading independent labels of the 1960s.

The Blue Smoke acetate

By 1960 Tanza had ceased to operate. The last 78rpm release on Tanza was 1958’s ‘Swingin’ Shepherd Blues’ by the Garth Young Trio, and the last 45rpm single was in 1959: the Keil Isles with ‘Sea Cruise’. Tanza’s third 10-inch LP was also its last – Ron Boyce at the Hammond Organ (1956), and there was only one 12-inch LP, National Band of New Zealand’s For the Bandsmen (release date unknown). There were also five 45rpm EPs released between 1957 and 1959: the Murray Pickett Quintet with their piano originals, two vocal rock’n’roll discs by the Q-Tees, Les Cleveland with New Zealand folk songs, and finally The Keil Isles with more rock’n’roll covers.

The Keil Isles' first EP, released on Tanza in 1959

In 1958 Radio Corp made a net loss of £16,000 – and there were import restrictions placed on records and other finished goods at that time. “So that’s about when they fell apart , they were actually taken over,” said Shears, who had left the company in 1953. Between 1958 and 1960 the majority of shares in Radio Corp were transferred to Pye. It remained a shell company until 1980, when winding up began. In 1982 the Pye companies were absorbed into Philips Electrical Industries Ltd, their parent company, and Radio Corp was finally wound up in December 1983.

As the first local independent label, Tanza was crucial to the development of the New Zealand recording industry. Following the publication of a Tanza discography by archivist Dennis Huggard in 1994, and the championing of the label’s recordings by broadcaster Jim Sutton, to a small number of collectors the discs became sought after again. In the 2000s much of Tanza’s catalogue was reissued by budget labels on CD.

Complete Tanza discography

Discogs has an incomplete Tanza discography, poorly ordered and dated. Much more useful is the complete Tanza discography, compiled by Dennis Huggard, which was made available online by the National Library of NZ in 2018. At this link, click on the words Book 1 TANZA Cat.DOC and it will download.

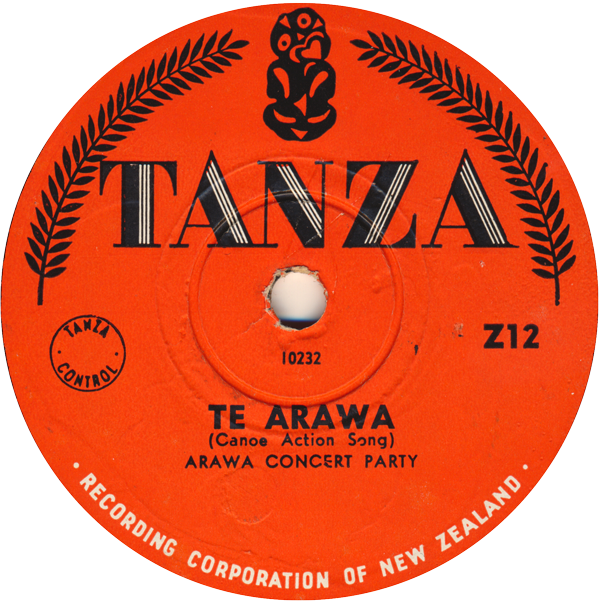

The Tanza 78 labels

The very first and most common Tanza label

The "Tiki" label is the rarest of Tanza labels, appearing on only a couple of releases

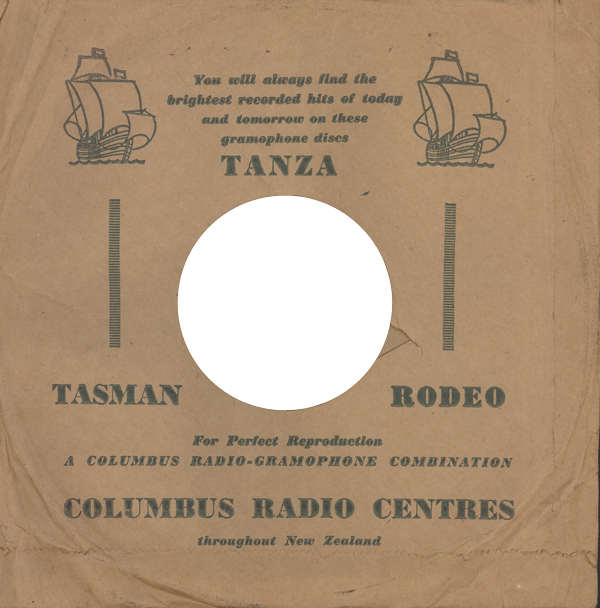

Tasman was one of three local labels used to issue recordings licensed from offshore, the other being Tempo and Rodeo

The Tanza vinyl labels

The first Tanza 7-inch label

The second Tanza 7-inch label

The final 7-inch label

The LP label

The Tanza bags

These were manufactured by the Wellington Paper Bag Company in Tory St.

The 78rpm bag was used throughout Tanza's lifetime

The first 7-inch single bag

The second and final 7-inch bag

The Tanza 78 releases were issued as follows:

1949 ended with Z15

1950 ended with Z50

1951 ended with between Z81 to Z89

1952 ended with Z157

1953 ended with Z209

1954 ended with Z232

1955 ended with Z275

1956 to 1959 Z276 to Z316

(research courtesy of Donald McLeod)

–

- Thanks to John Shears, Dennis Huggard and Gordon Spittle

Link to RNZ: The innovative company that changed radio in New Zealand