Sadly, Judd’s group The Swingers were unable to find a winning sequel to that smash hit, and they would be swiftly written off as one hit wonders, along with other momentary new wave novelties like The Motels (‘Total Control’) and The Knack (‘My Sharona’). More than 30 years later, it still seems wrong that the group faltered so quickly and subsequently came to such an undignified and ignominious end. There are just too many ‘what ifs’ to contemplate.

At least the home audience knew the truth: far from a one-song act, The Swingers had since its formation in early 1979 built up a formidable reputation as a flinty live act that refused to play anything but its own compelling and original material. It’s just that somehow, and rapidly, just around the time the trio should have been at its peak, the wheels were coming off; and that nobody seemed to notice it was happening.

But let’s go back even further in time (cue the disorientating wavy signal fluctuations on a groovy old black and white TV set to signal ‘backwards time travel’).

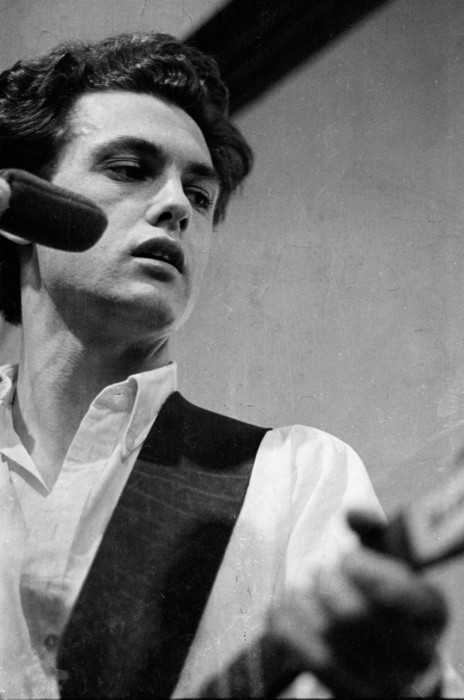

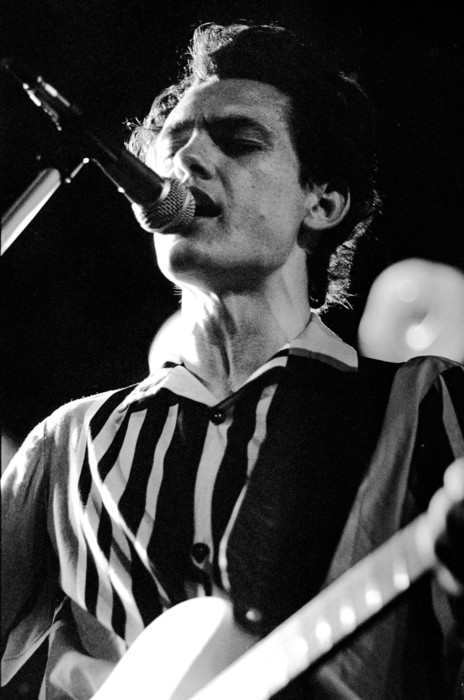

There’s probably no more enigmatic, eccentric, troubled or controversial figure to have come out of NZ pop than Phil Judd.

There’s probably no more enigmatic figure to have come out of NZ pop than Phil Judd, who was born in Hastings in Hawke's Bay, but whose musical journey starts in Auckland in 1971, when studying visual arts at Elam. It was there he met Tim Finn and Noel Crombie, and that association in the fullness of time begat Split Enz.

Even as Split Enz was really finding its feet in the mid-70s, Phil Judd was the voice of paranoia, anticipating by nearly a decade the post-punk Goth movement typified by groups like Bauhaus with his neurotic horror-vocals on songs like ‘Under The Wheel’ and ‘Spellbound’. Even though the group’s first album (Mental Notes) was saturated with proggy time signatures and Genesis Mellotrons, listening to the album now it sounds as if Judd was just waiting for punk to explode, and if you listen carefully, there are even hints of a latent pop sensibility that was to flower with The Swingers. It’s a long way from the centre-right pop the Finns propagated down the line.

Having ditched Enz in London in 1977, rejoined and ditched them again in 1978, Judd had announced his disenchantment with the music scene and his intention to explore a career in painting when he was lured into the tumult of Auckland’s exploding punk scene, expressing his love for Chris Knox’s band The Enemy and producing, then briefly joining, the Suburban Reptiles. In fact, he can be seen furtively slashing away at his guitar on the video of their ‘Saturday Night Stay At Home’, a high point of NZ punk singles.

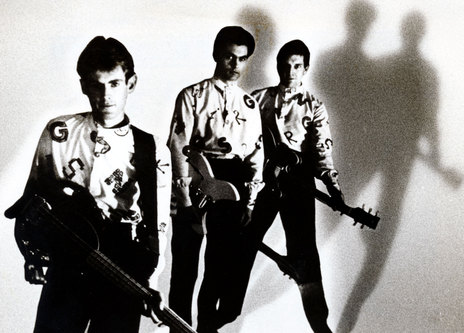

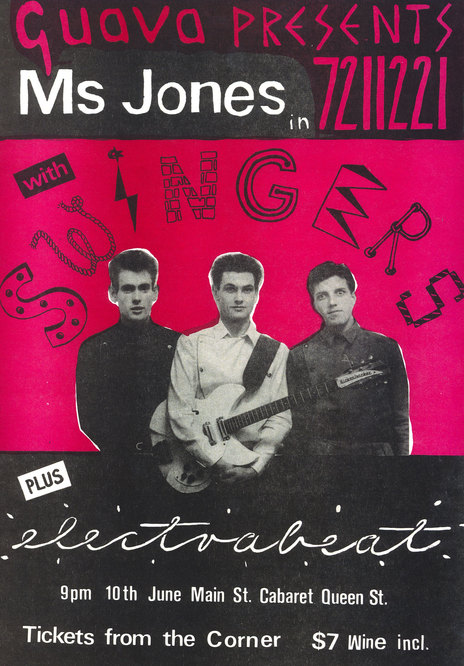

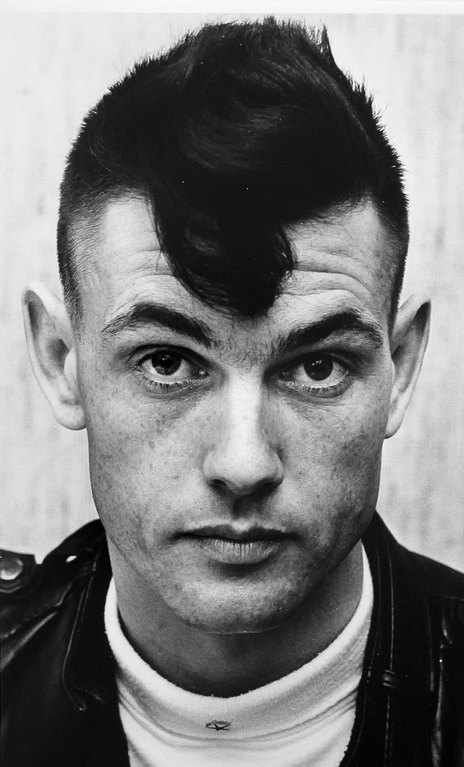

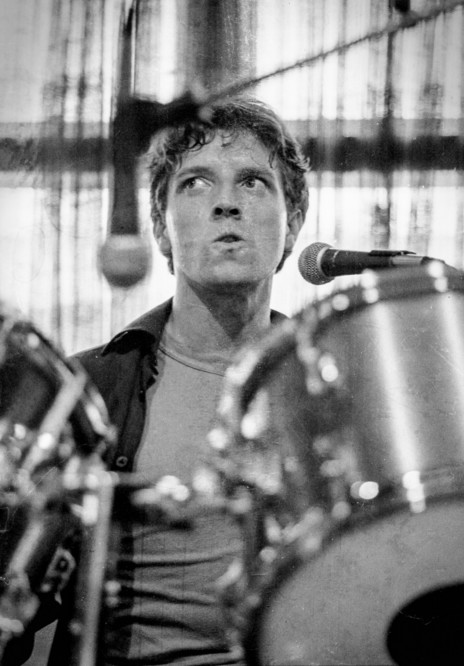

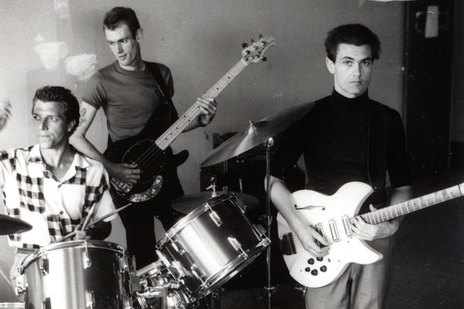

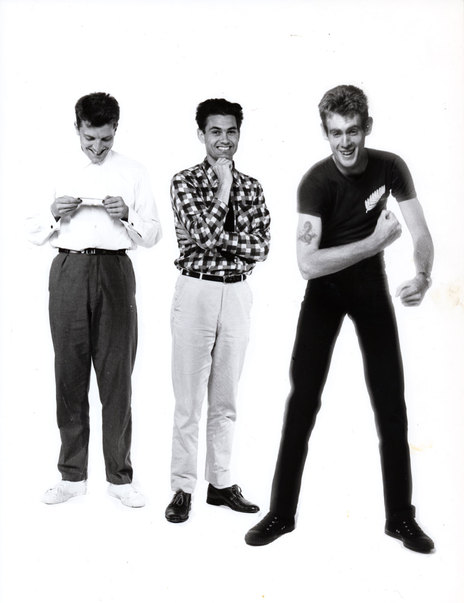

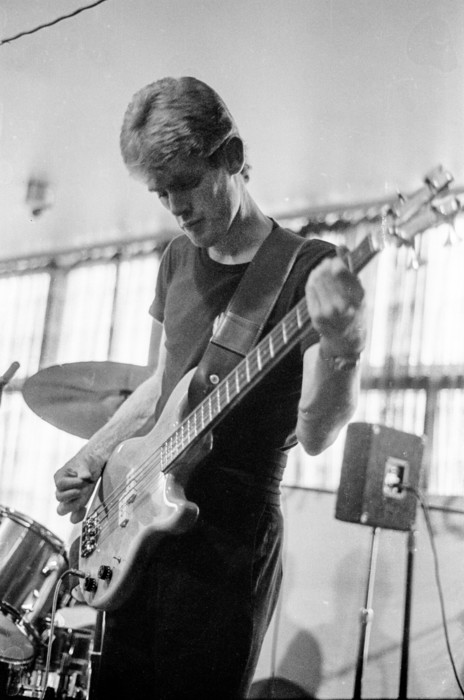

Then, the seemingly impossible happened: In March 1979 Phil Judd formed The Swingers from the ashes of the Suburban Reptiles, recruiting his old Hastings school chum Buster Stiggs (aka Mark Hough) and Bones Hillman (aka Wayne Stevens) to form the perfect pop trio.

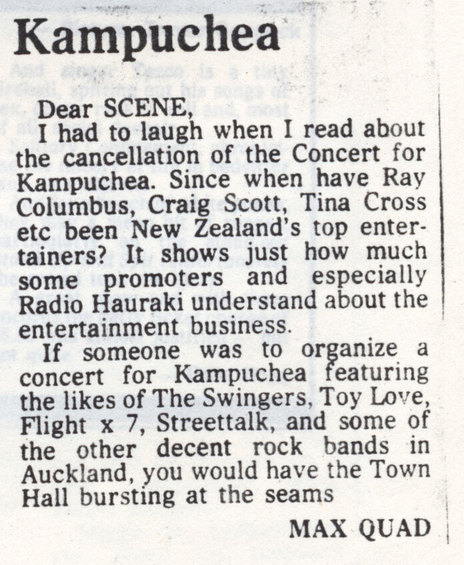

Although the punk movement had begun to revitalise the local scene, the lows of just a few years previous were still impacting on the industry and the general public, audiences generally felt that local bands were inferior to overseas acts, and they were supposed to show their subservience by obediently performing cover versions of international hits. The Swingers – possibly taking their cue from Split Enz – refused to play anything other than their own material. The reception to previously unheard material was patchy, with only eight people turning up to see them in Timaru on a Saturday night, and a dozen or so in Wellington. You really get a sense of the shock of witnessing an all-original local band from a story in the Otago Daily Times on December 12, 1979, written about the group’s second tour: “There are no cover versions with The Swingers – you either learn to enjoy their style of music or you leave.”

The group’s live debut after five months of intensive rehearsal was as support to Split Enz, where they were resoundly ignored by audiences.

The group’s live debut after five months of intensive rehearsal was as support to Split Enz, where they were resoundingly ignored by audiences, treated like scum by the roadies, and given terrible sound mixes. The upshot, however, was a two-month residency at a small Symonds Street venue, Liberty Stage, which built an audience and led to regular gigs around the traps, and a couple of national tours.

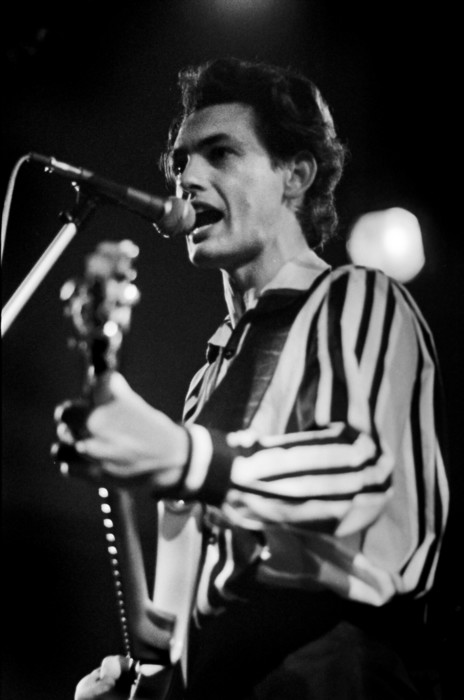

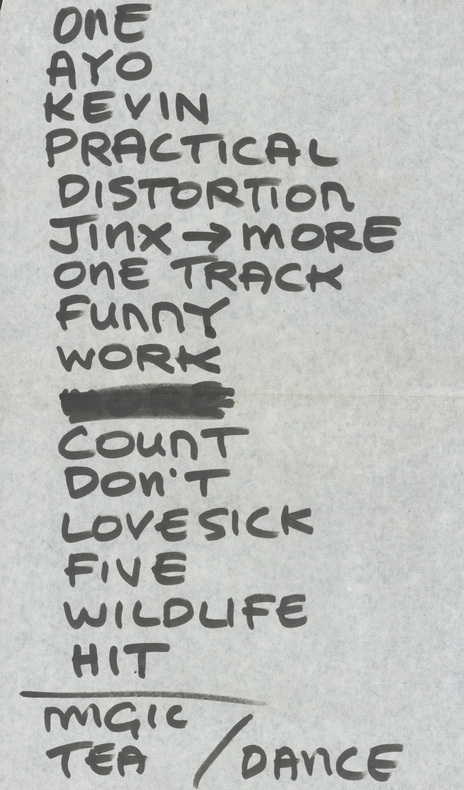

Their set list was full of hard-driving post-punk songs that somehow avoided cliché. Lean and tight and relying on the rhythmic interplay of just the three musicians and Judd’s caustic, incomparable vocal signature, the songs were full of sing-along choruses, but also took the piss out of sing-along choruses. With The Swingers, nothing was what it seemed, and like the smartest pop songs from earlier generations, there was always an element of self-satire, and self-awareness, that separated them from the dumb bluster of the pub-rock new wavers.

Unfortunately, however, right from the start there were signs of Phil Judd’s less sunny side, and temperamental character traits that would often see good work undone. Former Split Enz bassist Mike Chunn has noted that Judd was not given to idle conversation, and uncomfortable in social situations. “He was not a social character. He had difficulty being gregarious. I was Mr Agorophobic and he was Mr Antisocial.”

NZ music historian John Dix wrote that in The Swingers’ live performances, Judd had no rapport with the audience, and would turn his back on the crowd between songs, leaving it up to Buster to muster some banter from the drum stool. While The Swingers were considered a strong live proposition and were particularly popular in Christchurch, it wasn’t for the act or the stage presence, but for the sheer quality of the songs and energy of the performances.

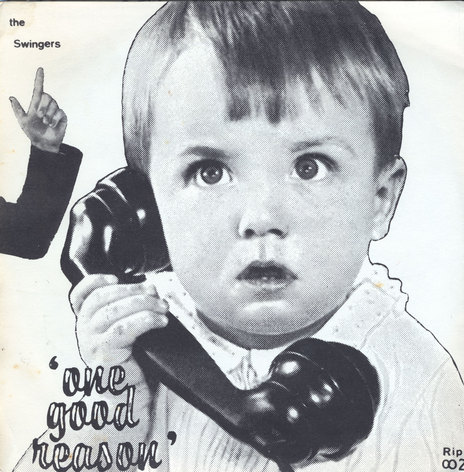

They returned to the studio with Mike Chunn in the producer’s chair to record ‘One Good Reason’, released on the independent Ripper label.

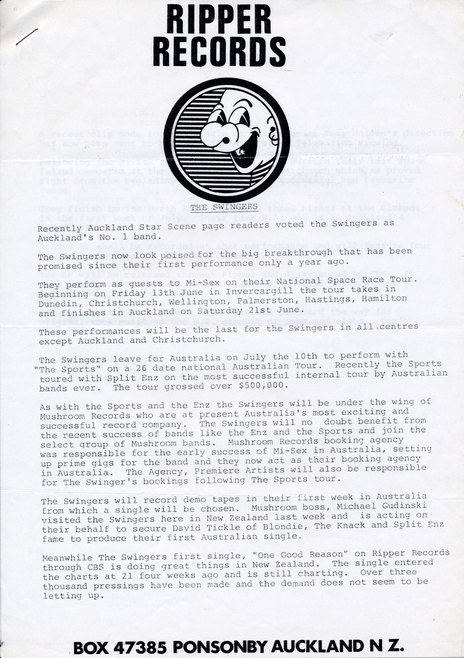

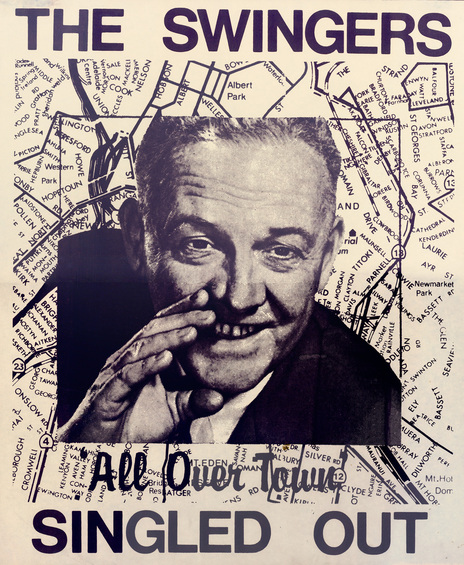

Early on, the trio recorded a bunch of demos at Mascot Studio from their selection of 20 original songs; test runs that have never officially seen the light of day. A matter of months later, they returned to the studio with Mike Chunn in the producer’s chair to record ‘One Good Reason’, released on the independent Ripper label (with distribution through CBS). It made a respectable No.19 on the local charts in April 1980, a humble achievement that hardly reflects the legendary status this song still holds amongst NZ pop music aficionados.

Time itself would get stuck on spin cycle from this moment on for The Swingers, who had begun to receive the advances of Australian Mushroom Records head honcho Michael Gudinski. Shortly thereafter, in July 1980, they headed off to Melbourne, where in an unlikely match they played support to dull Aussie rock band Sports, and began working with English producer/engineer David Tickle, who had successfully rejuvenated Split Enz’s ailing career the year before.

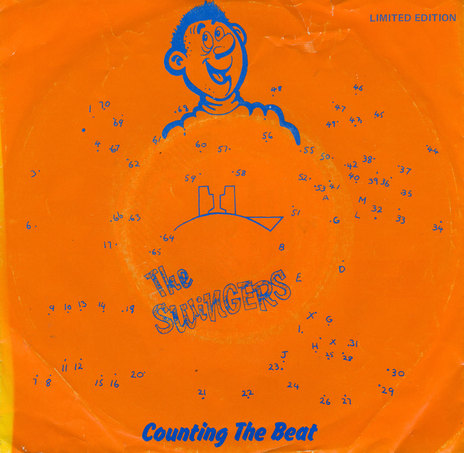

The result was a re-recording of ‘One Good Reason’ and the song that would come to define them – and become the millstone around their necks – ‘Counting The Beat’. They can’t have known it, but before that giant hit was even released, they had sewn the seeds of their destruction. Recorded in July 1980, a final mix of the song was ready in November, but it didn’t get the green light until January 1981. The rest is history.

But in the interim, Judd and Hillman had struggled to survive in a grotty Fitzroy St flat while Stiggs had lived in comparative luxury with Neil Finn and Noel Crombie, resulting in the drummer’s estrangement and quick-fire expulsion. While Stiggs got a job in successful Aussie band The Models the day he left The Swingers, Ian Gilroy – who had been Bruno Lawrence’s replacement in The Crocodiles – joined The Swingers just in time for sessions for their debut album. All the other unreleased songs that Kiwi audiences had learned to love were dropped and brand new material worked up for the album. But while ‘Counting The Beat’ was a phenomenon all on its own, attempts at follow-up hits were failures.

In the online comments section of Simon Sweetman’s 2009 interview with Phil Judd, Buster Stiggs proved that enmity is still alive and seething. “Juddzy and I had known each other since high school and were a great team,” he wrote. “The magic we produced in our two years of songwriting was mostly put in the bin by Juddzy who chose to write a new batch of songs for The Swingers album. The only regret I have with The Swingers is that all those initial great songs were never recorded properly, and were not on The Swingers album – ‘All Over Town’, ‘The Jinx’, ‘Over The Teacups’, ‘Baby’, ‘Shoana’, ‘Work Here’, ‘Louisa’. These were the songs that established The Swingers as the most popular band in NZ. They were tried and proven on pub audiences and then they were ditched for the album. In effect, that two years of blood, sweat and toil getting that original repertoire together was for nothing. An album with those songs would have made more of an impact than the songs Juddzy hastily put together for The Swingers album. They sounded like the rhythm track was a drum machine – there was no band vibe or energy. Too bad too sad.”

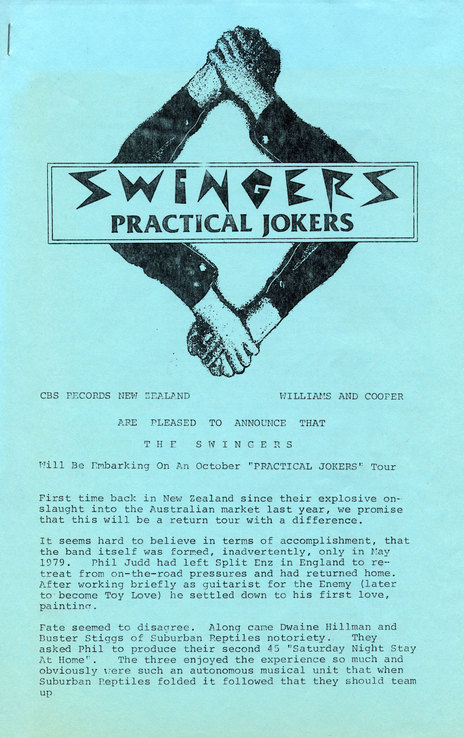

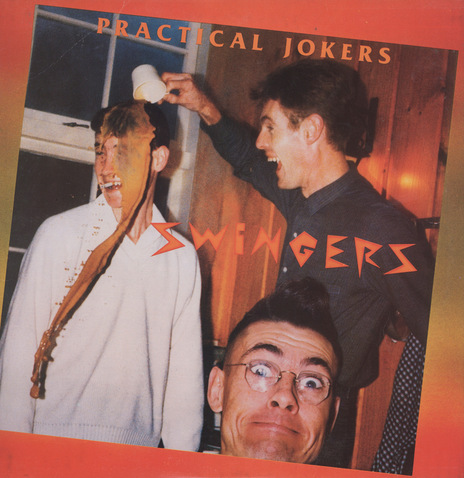

After the spectacular success of ‘Counting The Beat’ (released January 19, 1981) the group performed around Australia, but everybody just wanted to hear the hit. By the time ‘It Ain’t What You Dance, It’s The Way You Dance It’ rolled out in June, the magic was gone, with dismal sales in Australia and moderate success in NZ. A third single, ‘One Track Mind’, hardly did any better. The Practical Jokers album received mixed reviews and sold only moderately, and when the group toured NZ later in the year, they seemed road-weary and sullen, despite an uncommonly great PA and stage dressing. I saw them at Wellington’s St James theatre, where they failed to engage the audience, appeared to have attained an Aussie rock thud, and the audience constantly trickled towards the exits throughout the performance.

By the end of that year, Andrew Snoid/McLennan (Whizz Kids, Pop Mechanix, Coconut Rough) had been recruited on vocals and keyboards, a bizarre decision that totally changed the group’s sound and inevitably led to Judd firing the whole band and ending the saga of The Swingers in May 1982.

The sad story of The Swingers ends there, although ‘Counting The Beat’ re-emerged as the soundtrack to a TV ad in the 90s, and in 2001, the song would be voted in an all-time fourth placing in a list of ‘Best New Zealand Songs Ever’.

Meanwhile, Judd’s fascinating odyssey continues, with many fans acclaiming him as our lost music genius (or NZ’s very own Syd Barrett). Like the international success that Kiwis expected of Hello Sailor and Straitjacket Fits, the failure of The Swingers to take on the world remains one of our most perplexing non-events.

The cultural legacy of The Swingers? Surely, they were New Zealand’s smartest, most singular pop band of the era. And underneath the hooks and the taut rhythms and the strangely vulnerable whine of Judd’s vocals was enough pure pop psychosis to make a thesis out of.

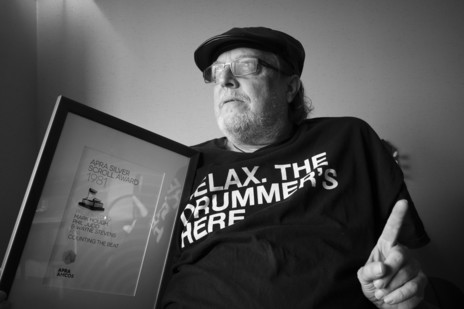

After a long struggle with ill health, Buster Stiggs died on 7 January 2018, and Bones Hillman passed away at his home in Milwaukee on 7 November 2020. Phil Judd, on his Facebook page, wrote: “Me old bandmate Bones Hillman (Swingers/Midnight Oil) has passed away today. A great guy and wonderfully intuitive bass player. The Swingers’ band practices and gigs were the highlight of my musical life. Jamming was heaven ... whenever I’d start playing some ad-lib twaddle they’d both click instantly ... it was wild! Compared to Split Enz where everything had been slow and laboured, Bones and Buster were never without energy and boundless enthusiasm.”