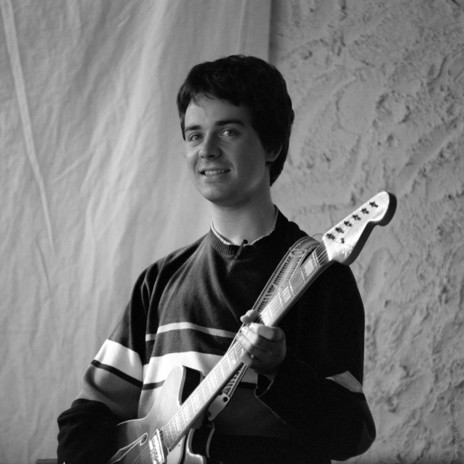

Martin Phillipps, taken in London, probably Bonnington Square, Lambeth, 1985 - Terry Moore

Jane Dodd

I met Martin in the beginning of 1972 (no, that’s not a typo) at George Street Normal School. It was a teacher-training school, and our particular class was a model of a country school with many years and ages. As there were just six of us in Standard 3 we got to know each other well. But it was at high school in our mid-teens that we became really close buddies. We both played guitar and loved music, although our tastes were quite different, and we argued a lot. I remember the day after Devo were first on New Zealand tele. I said they’d be a flash in the pan – he was lit up!

Model 1a, George Street School, Dunedin, 1972. Martin Phillipps top row, second from left; Jane Dodd middle row, fourth from left. - Courtesy of Jane Dodd

Late 1979 Martin asked me if I’d join The Same playing bass. I was initially reluctant because I really wanted to play guitar, but also desperately wanted to be in a band. We played a few self-organised gigs at community halls, the Logan Park High School formal, supported Toy Love at the Captain Cook, and entered the Downtown Tavern Talent Quest (none of us yet old enough to be in the Tavern). We got called back the next week for the finals as the judges “just loved our energy!” We didn’t win.

The Same played a few covers, quite badly (‘Surfin’ Bird’, ‘Where Did Our Love Go’, ‘Waiting for the Man’ …) but a proto-songsmith was also emerging. The Same morphed into the Chills in late 1980 and the songs got smarter. It was glorious and exciting to experience.

Martin was an early car owner. We went on several adventures. Once, he, Peter Gutteridge, and I went to Te Anau for a night. When we got there (staying at someone’s crib) we found there was no bedding. So the three of us slept all together between two mattresses. Chills sandwich!

Jane Dodd, a member of The Chills and The Verlaines, went to intermediate and high school with Martin Phillipps

The Same play Logan Park High School formal in 1980. Martin Phillipps, Craig Baird (obscured), Jane Dodd, Rachel Phillipps. - Courtesy of Jane Dodd

John Dix

I met Martin Phillipps in August 1980, a month after his 17th birthday. Toy Love was playing three nights at Dunedin’s Captain Cook Tavern, followed by a Sunday afternoon under-age rage at the Concert Chamber, with several local rising bands, including The Clean and Shayne Carter’s Bored Games. Marty was peeved that his group, The Same, had been overlooked.

Targeting Chris Knox as the person most likely, he arrived at the band house every day after school, pestering Chris and anyone else to get on the bill. His persistence paid off. Later that year, he changed the band’s name to The Chills.

We were almost neighbours for a spell, he in Dunedin, me in Queenstown. He played my QT club three times. The first occasion was a shambolic audio-video experiment, punters left in droves. The second time, solo, he played nothing but new material, not what the paying public wanted. The third time was Pay Back, a three-night dry-run for a forthcoming tour supporting Split Enz, with full band and Chills hits in the mix.

I must confess that I didn’t recognise Martin’s musical talent during The Same’s 1980 performance, but I soon caught up. Eighteen months later I produced a radio history of New Zealand rock’n’roll. To end the series, looking ahead, I chose The Chills’ ‘Kaleidoscope World’ from the just-released Dunedin Double EP, one of only three Martin Phillipps songs then recorded. This, I maintained, was the future of Kiwi Rock. I still reckon I chose well.

What a career, what a legacy. New Musical Express once opined that ‘Leather Jacket’ featured “the last great rock’n’roll riff”. Great song but the song I regard highest is ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’, exquisite melody, intriguing lyrics, a near-perfect slice of pop,.

Martin once told me “None of the Chills’ songs sound as good on record as they do in my head.” That may be but this will have to do and, hey, it sounds just fine, Marty. Thanks for the music, Martin Phillipps, thank you for your resilience and self belief, you have left behind a remarkable catalogue of endearing gems.

Hei whakamaharatanga mo te hoa pai …

John Dix wrote the seminal New Zealand rock’n’roll history Stranded in Paradise

Martin Phillipps and Francisca Griffin. - Courtesy Francisca Griffin

Francisca Griffin

I met Martin in early 1982 when my partner Martyn [Bull] auditioned to replace Alan Haig on drums; he passed that audition and The Chills phase whatever was born. Intensive practise commenced and off they went on tour in the newly purchased Chills van, with a big tin full of brownies I’d baked for the trip – no, not that kind – which was a good thing coz they ate them all before they’d even reached the Chills bridge!

‘Pink Frost’ was recorded at the end of that tour in Auckland by Terry, Martyn, and Martin, the pared-down next phase of The Chills (my favourite). He and Terry [Moore] came to our wedding in Masterton in December 1982. Terry, my Dad for the day, and Martin best man. Both looked resplendent in rented 70s suits, Martin’s was blue of course!

In 1983 after Martyn died, Martin – after much considering, in which he so graciously included me – decided to change the name of his band to A Wrinkle in Time. That didn’t last – because it was always The Chills, wasn’t it? Martin brought me a copy of Secret Box before it was released, he wanted me to have a copy because Martyn is on it. He was quite thoughtful that way, making sure to include me when he could.

Martin, the forever fragile boy in a man’s body had a singular, some might say obsessive, idea of where he wanted his music to go. I think he did spectacularly well at it, despite all the falters he had along his way. He’ll be cheering on the music makers of Dunners forever now. Aroha nui e hoa.

Francisca Griffin (Look Blue Go Purple) is an Ōtepoti Dunedin musician

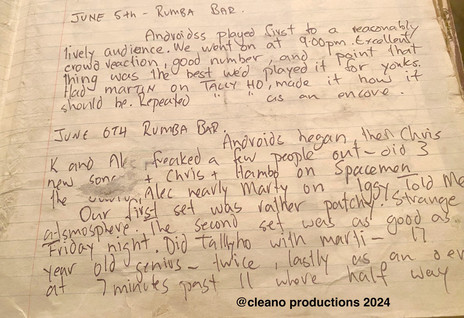

The Clean diary, mentioning 17-year-old Martin Phillipps - The Clean

Richard Langston

Thank God they invented guitars. Without one, Martin Phillipps might have struggled to ever set foot on a stage. He was that shy. In his early days he felt inadequate as a performer and envied those who carried it off with gusto. But Martin could write songs and had better muscianship than many of his contemporaries who were inspired by punk. There’s an entry in The Clean diary when they play the Rumba Bar in 1981 and Martin plays keyboards – “Did Tallyho with Marti – the 17-year-old genuis” [sic].

He never knew about that entry until I told him about it earlier this year. He was chuffed, and modest enough to still appreciate it. No matter all the awards and accolades his work had earned him, the opinions of his fellow Dunedin songwriters were what mattered at the centre of him. A few years ago, when I asked the Australian musician, Robert Forster, to sign a copy of his book about life in The Go-Betweens to Martin, he inscribed a note saying he thought of ‘Pink Frost’ as New Zealand’s national anthem. It might be a bit broody for the gold-medal ceremony at the Olympics, but it certainly spoke of our whenua, our seas, and our weather.

He wrote the song ‘Submarine Bells’ when he was 26 or 27, realising every beautiful sound and thought in his mind and body. The next time you hear someone say he wrote jangle-pop, remind them he could write orchestral pop of that calibre.

My favourite memory of Martin is of him in the 80s coming to visit us at the house where we produced the fanzine Garage in Dunedin. He arrived in his new pride and joy – a maroon vintage Rover – flush with his first success in the UK and bristling with the brilliance of his songwriting road ahead. There’s a photo of him standing beside it, dressed in a baseball cap and day-glo surf shorts. I’m not sure if he’s thinking of going for a round of golf or mind-surfing to the Beach Boys.

People could underestimate his droll sense of humour. But never his good heart. We could hear the symphonic sound of that in his songs.

Richard Langston, a journalist and broadcaster, edited Garage in the 1980s

Martin Phillipps and his Rover. - Courtesy of the Phillipps family

Terry Moore

In the early 1980s the Regent Theatre in Dunedin rented out to bands its old, dilapidated office spaces on the upper floor of the main building that faced the Octagon. Bored Games had a room at the same time as The Chills had one just across the corridor. The place was not soundproof, so you could hear everyone and at times it was a cacophony.

At some point I was in The Chills practice room listening to them play ‘Silhouette’, Green Eyed Owl’, and other songs from that era. Afterwards Martin suggested we get together one afternoon; we did not know each other well at the time.

We met in the Bored Games’ practice room one dreary Dunedin afternoon, accompanied by some beer. After some time chatting while we plugged in, tuned up, sipped, and tweaked amps, we connected quickly talking about music we liked. Syd Barrett – check, Beach Boys – check, Buzzcocks – check, etc, etc. The Venn diagram was heavily overlapping!

Once we were set up, we were still chatting and unclear on what we would play together. Martin said he had a new song that he was working on for the Chills. I said, let’s hear it! Martin started playing it. It was melodic, strummed, but also had intricate picking on transitions. It was an embryonic ‘Rolling Moon’ verse (no lyrics at this point). It sounded too folksy for my tastes, so I tried some counterpoint with what, in my mind, was reggae-derived “bass and space.” We played around with it for a good hour, or until the beers kicked in!

From this formative engagement we bonded, and I subsequently joined The Chills with full belief in the project, and later my flatmate Martyn Bull joined the mix. What happened over the next 10+ years was a source of both frustration and jubilation. Martin had a singular focus and a sole purpose in his life. That is almost religious in nature. There was friction I and others experienced, but I love Martin, I truly do, and always will. I hope that his vast reservoir of wonderful songs will somehow get out into the world and be recognised for the amazing life-long artistry that Martin pursued.

Terry Moore, now based in New York, was bass player with The Chills during the 1980s

Martin Phillipps during the Looney Tour, at the White Hart New Plymouth, during sound check. Photo by Terry Moore

The Chills, 1985 - Alan Haig, Peter Allison, Terry Moore, Martin Phillipps

Peter Allison

In 1983 a job ad in Roy Colbert’s Dunedin record store changed my life. “Keyboards player wanted.” For a below-average pianist who had struggled through childhood lessons, it seemed like a golden opportunity. I went to an audition with an intense young man named Martin Phillipps and his cool bandmates, Terry Moore and Martyn Bull.

Little did I know that The Chills would evolve into one of New Zealand’s most iconic bands, or that Martin would join the pantheon of great singer-songwriters.

But it was clear even then that Martin was a musical genius. So much imagination, so many songs. The next three years were a huge adventure. Playing the excellent early Chills catalogue (‘Kaleidoscope World’, ‘Rolling Moon’, ‘Pink Frost’, ‘Night of Chill Blue’, ‘Oncoming Day’, and many others), moving to Auckland (the Windsor Castle and Gluepot among regular gigs), recording ‘Doledrums’ and The Lost EP, touring the country several times then heading off on the band’s first overseas trip to the UK, where we played gigs in London and Brighton and recorded a John Peel session and ‘I Love My Leather Jacket’.

The Chills, in a mid-80s publicity shot (L-R): Alan Haig, Terry Moore, Peter Allison and Martin Phillipps

It wasn’t always easy – three of us left the band on our return – but Martin’s vision and drive never wavered. He rebuilt The Chills and moved on to bigger and brighter things: extensive European and American tours, and critically-acclaimed albums. He came close but was desperately unlucky not to crack the international big time as he so richly deserved.

Enough has been said about Martin’s difficulties in holding the band together, and its many line-up changes. What was remarkable was his perseverance and resilience. While most former Chills – and indeed, most Dunedin Sound alumni – moved into other fields, Martin kept the flame burning, despite trials, tribulations and health issues, all the way into his 60s. It’s worth noting that the band’s most recent line-up has spanned nearly two decades, and that in 2024 Martin was working on an album of unreleased early songs which he hoped to tour later in the year. Still loving his kaleidoscope world, right to the end.

RIP, Martin. Gone too soon, but his songs will live forever.

Peter Allison played keyboards for The Chills from 1983 to 1986

The Chills in Berlin, c.1987. From left: Caroline Easther, Martin Phillipps, Andrew Todd, Justin Harwood. - Caroline Easther collection

Caroline Easther

Holland, mid-February 1987

We’ve stopped the van for gas and unfamiliar candy bars. Our manager Craig Taylor has taken off the engine cover to check the oil. Martin has found the engine cover and is holding it up in front of himself and lurching around the forecourt being a robot.

Now: July 2024

My friend Alan calls, the day after we’ve heard Martin has died, and we meet up for a coffee. Alan had been there in 1987, changed strings at London gigs, hung out. We’d slept together on the floors and sofas of whoever would have us. Such kindness. It often seemed surreal then, and we just wanted to check we weren’t dreaming now, I think. To reassure each other. To remember. “Fill your head with alcohol, comic books and drugs,” Alan said as he sat down.

I love drumming. I loved playing that song. A labyrinth of chords. So clever. Such energy. Then I watched The Triumph and Tragedy of Martin Phillipps and there he was. For 23 years people had asked me what Martin was like, how was he to work with. And now I could answer. He did a lot of business in his head. He was not always a great communicator. He was unique and vulnerable, and at his best when up to his neck in music stuff. I had to stop myself grizzling about how tough it was in London, being left to fend for ourselves, broke and homeless. It wasn’t his fault. We can’t be all things and Martin at centre could only deal with so much on top of the music. I know it surprised and upset him when he realised how difficult it had been for us, his band, at times.

We didn’t talk together much. I knew I liked and admired him and his songs, his music, his ideas. I was very ignorant about music back then, so we didn’t have much in common. He was very funny. I was a bit uptight. Struggling a bit, while realising I was having the adventure of a lifetime. It’d be different now. I think we’d laugh a lot more. I’m so glad to have been a part of The Chills’ story.

“This is the way. This is the only way for me.”

Caroline Easther played drums for The Chills and Let’s Planet during the 80s

Craig Taylor

My introduction to the Chills came via Dean Allen, who was on a visit to London from Dunedin in late 1984. I awoke to a loud, aggressive doorknocking. Upon answering the door I was brushed aside with a demand for directions to my turntable. A 7" single of ‘Pink Frost’ was produced and played at full volume on repeat a dozen times, before starting on the B-side. This was not of the Dunedin music scene I had left behind some five years earlier. So began my infatuation with The Chills and love affair with Flying Nun. What a rollercoaster it was about to become.

Over the following years, I was lucky enough to become involved with The Chills and the label. We toured the world playing countless shows from Oslo to Invercargill and everywhere in between. Martin was always a pleasure to work with, through the good and the difficult times. Through lineup changes, adversity, and the sheer physical grind that is the nature of touring. He was always positive, genuine and generous with his time for everyone he encountered on his journey. He never lost his childlike enthusiasm and wonder at life. His wonderful gift of songwriting never diminished and his legacy is immense. I am proud to have been a part of his story in some small way.

Craig Taylor managed The Chills in the UK, where he promoted Flying Nun acts

The Chills and friends in the band room, somewhere in the Netherlands, 1987. Taken on timer by Simon Alexander. Back row: Andrew Frengley, Lisa Coleman, Simon Alexander, Justin Harwood. Centre row: Martin Phillipps, Kate Tattersfield, Craig Taylor, Caroline Easther. Russell Brown is at the front. - Martin Aston

Colin Hogg

I wear my leather jacket like a great big hug

Radiating charm – a living cloak of luck

It’s the only concrete link with an absent friend

It’s a symbol I can wear till we meet again

Or, even harder to hear now:

No way

No way will I give in to the oncoming day

The oncoming day!

I’m not one for exclamation marks, but Martin Phillipps sure knew when to use one there. He was, as they say, one out of the box, in his case, the rather dark and dour boxful of Flying Nun bands. While everyone else was muttering darkly, or, more alarmingly, not muttering at all, Marty was the smile in the room, the dreamer, the eternal child-adult who truly believed in the power of music, in the holy quest for the perfect pop song.

He made a few of those and he paid a price, of course. The critical delight that greeted The Chills and persisted here and around the music-loving world through the decades was never matched with earthly rewards. Martin often struggled just to exist. But, despite that and the famously ever-evolving line-up of The Chills, he never seemed to stop believing.

Or stop making music that was utterly original, naïve, marvellous, sad and happy, sometimes both at the same time, and not quite like anything else, which is the trick of course.

But, in the end, perhaps there were just too many oncoming days.

Colin Hogg is a music journalist, author, and television writer-producer

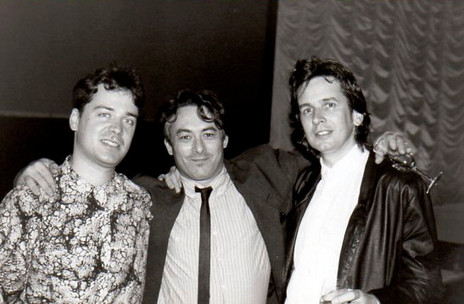

Martin Phillipps, Doug Hood and Colin Hogg

Doug Hood and Jack Oliver-Hood

We are still coming to terms with Martin’s death. To Doug he was a treasured friend, sadly gone too soon. They went through some amazing times together, touring and recording in the 80s and early 90s. Even after all the time that has passed, we saw Martin at the Powerstation back in May 2021 and he was as amazing as ever. To Jack, he was Uncle Marty, a warm and kind godfather. Jack’s first memory of music is hearing ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’ and being completely transfixed. Martin will be terribly missed.

Doug Hood and Jack Oliver-Hood: what didn’t Doug do for The Chills? Jack is his son

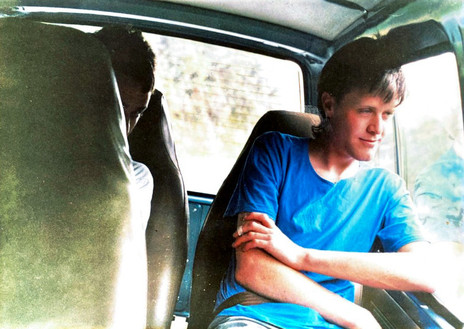

Martin Phillipps and Andre Upston on the tour bus, North Island, early 1987. - Caroline Easther

Andre Upston

The loss is impossible to articulate.

As a performer, Martin was kind of like The Incredible Hulk. It’s a cheesy analogy, but that is truly how I felt. I watched in awe while also recording The Chills live personally and a couple of times professionally, from 1985 all the way through to 2019. Martin was so quiet off-stage, almost introverted, but when the mighty Chills machine roared into life on-stage, he was a man transformed, a man possessed. It was almost as if he was way more comfortable enveloped by that beautiful wall of melancholy volume on-stage, than he was anywhere else.

Martin’s generosity

Years before Secret Box came out, he borrowed two cassette players and dubbed and then sent me two 90-minute cassettes with the best of the Same and Chills recordings he had collected. With that amazing treasure trove of audio were pages of hand-written notes, describing in detail why that particular version (of mostly unreleased songs) had been chosen … it must have taken him ages!

1987 (I was 20)

When the band found out I was going to bus around the North Island to catch every show, they invited me to become part of the road-crew. I managed to dent the roller-door of the rental truck on the very first night.

When that same line-up returned from a huge European tour, Martin brought back for me these super-rare, white-label test-pressings and flexi-discs of various Chills songs. Who else would do that?

An RNZ session

One time at the Helen Young Studio, Martin came in with only a Casio keyboard and a dictaphone (his 4-track had broken down). On the dictaphone were about 20, extremely lo-fi, individually recorded vocal ideas that would hopefully form the piece of music he wanted to assemble over the next couple of days. Layering multiple keyboard passes one-by-one, this piece of music only Martin imagined would work together, became ‘Autumn Testament 20’, eventually released on the Baxter album in 2000.

Thanks for everything Martin. You welcomed me into your amazing world. Through those incredible songs, myself and anyone else who is lucky enough to be drawn into their orbit, never has to leave.

Andre Upston is an Auckland-based recording engineer who works at RNZ

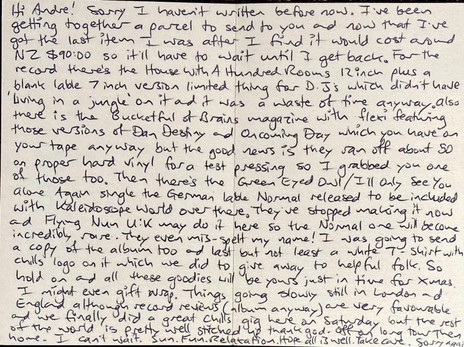

Martin's card from Europe, 1987. - Andre Upston

Stuart Page

I drove to Dunedin in September 1983 to stay with some musician friends who had rented a house at Broad Bay where they were extracting psychedelic alkaloids from South American cacti that they were growing. One day after imbibing said potion, we drove off to Taiaroa Head to explore the World War Two tunnels. I remember Martin being particularly “devilish” – leaping out of doorways and frightening the hell out of us in the dark. He had devised a technique whereby you held down the gas pedal on your Bic Flic lighter and ran the flint wheel down the wall of the tunnel, creating an amazing jet of sparking fire, which to our already heightened senses seemed totally magical!

Martin Phillipps and Stevie McCabe at the Crown Hotel, Dunedin, 22 May 2015. - Photo by Stuart Page

Later in the week at the Empire Hotel, we encountered two teenagers with guitars about to play, and no drummer. I quickly occupied the vacant throne, and before you know it the AXEMEN were born. The following night at another show, Marty became visibly infatuated with Stevie McCabe’s songwriting and performance, dancing and shouting out right up by the stage. Of course, Stevie soaked up all this attention from someone he very much respected himself. This mutual attraction continued for decades, Marty attended every AXEMEN show if he was in town. I’d receive a very polite message requesting his name be added to the door list. Martin would arrive very early, and we’d all sit around drinking a few beers, and discuss songs, and everything else.

In 2017 after a change in plans I discovered that I wouldn’t be in Christchurch to see Martin open for Aldous Harding, and the Auckland show at the Civic had sold out. I contacted Marty and he arranged for me to attend the show. In the end a close friend of mine had a spare ticket right up front, so I was able to enjoy Martin’s solo set, and Aldous’s performance, in a very close, intimate setting – that was the last time I saw Marty perform.

Stuart Page is a musician (AXEMEN), photographer, and filmmaker

Graeme Humphreys

Graeme Humphreys and Martin Phillipps at the Empire Hotel, Dunedin, Nunfest 96. - Photo by Natasha Griffiths

Graeme Humphreys on his first encounter with music of The Chills: “I remember where I was. It was a lunchtime in 1981 when a brooding aching gentle thrum from bFM’s quad speakers at Auckland University made everything around me stop. It was immediately very important. It was Dr Who, Syd Barrett and Prokofiev all at once, yet greater than the sum of those parts. It was The Chills’ ‘Satin Doll’. I’m still seriously stirred when I hear the bit where that song gathers up its gear and marches. Years later I’d be in a band in the same van and had the privilege to see Martin up close. He was so gifted sometimes he’d glow in the dark, as I recall, vibrating blue-green with glistening gilded edges.”

Graeme Humphreys is a musician (Able Tasmans, Humphreys and Keen) and broadcaster

--