The records discussed in this two-part article (read part one here) fall very much into the Popular Music bag. They’re “authentic” only in the sense they were made by mainly Polynesian men and women during the mid-late twentieth century.

Do the tracks collectively represent Polynesian culture? No, but I believe they are – as cultural historian David Mellor coined – “little narratives”. Looking at, listening to and talking about them might be one way to understand more about Aotearoa and the wider Pacific’s cultural history, both good and bad.

I first came across the records in second-hand stores, surprised by their ubiquity and the LPs’ unusual visual presentations. After listening, I understood that the sounds were a fusion, an on-going collaboration across three decades that brought Polynesians, Māori and Pākehā together for the purposes of entertainment. That still strikes me as a positive achievement. Others may disagree.

But that’s the problem/beauty with art. Once it’s free and in the wild, geeky enthusiasts like me tend to engage with it and insist on asking daft questions like: “What’s this all about then?” If no answers are forthcoming then you do your best to piece together a few of the “little narratives” until they cohere. What you get is just a slightly longer narrative but it’s never the whole story.

Trio Samos, left to right: Eddie Eves, Bill Speman, Bedivere Eves, in the NZBC studios in Shortland Street, Auckland, c. 1963. - Photo by Alton Francis, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints 02522.

In these pieces and other articles I’ve written for AudioCulture I’ve touched on aspects of colonialisation, misogyny and tourism-related exploitation. They were an insidious presence when these records were being made and tragically they are an insidious presence now as new music is being created.

But jumping out of the grooves of these old LPs are enthusiasm, skill and beauty – and, to me, those are attributes worth celebrating.

--

The Samoan Surf Riders – ‘Mauga Ole Tatuolo’

The Samoan Surf Riders - Let Me Hear You Whisper (Octagon/Viking, 1964)

There’s a fair amount of affection for the Samoan Surf Riders, and when their records come up in music conversations they tend to evoke a nostalgic reverence.

A lovely 2018 article by Graham Reid (based on an interview with the late Horst Stunzner – a member of a 1964 Surf Riders line-up) gives some fascinating context and family background but doesn’t completely explain their somewhat convoluted history.

Here’s what we know, sort of: The Samoan Surf Riders (backed by Bill Sevesi and his Islanders) began their recording life in 1961 with the Viking LP Aloha Samoa. It is, I think, their best album but frustratingly remains unavailable in the digital domain. The line-up at this point was Malu Natapu, Rudy and Hugo Spemann and Eddie Eves.

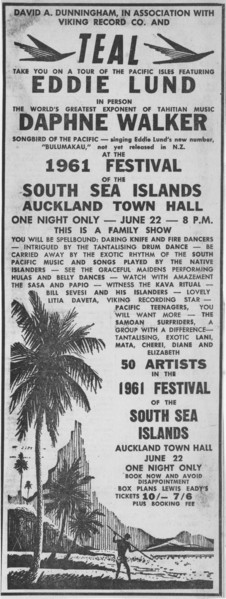

An advertisement for Eddie Lund and Daphne Walker headlining at the Festival of the South Seas Islands, Auckland Town Hall, 22 June 1961. Promoted by Dave Dunningham in association with Viking Records and TEAL airlines, the show included The Samoan Surf Riders and Bill Sevesi and His Islanders. - Dave Dunningham Collection

The group’s photograph on the back cover of Aloha Samoa however, actually shows Bedivere Eves rather than brother Eddie. Bill Spemann Jr (Rudy and Hugo’s nephew) recently confirmed to me that Bedivere was indeed involved with the Samoan Surf Riders during these early years.

Winter 1961 saw the group performing in Eddie Lund’s Festival of the South Seas at the Auckland Town Hall. The Auckland Star reviewer was impressed, calling them “… a group of singers almost in the Kingston Trio class.” High praise indeed in the pre-Beatles era.

After the release, in late 1961, of a live recording of the South Seas show, two new Samoan Surf Rider studio tracks appear on the 1962 The Beat of the Pacific album. Also that year, Viking went back and mined four tracks from the Aloha Samoa LP and released them on an EP titled Goin’ Samoan.

It’s around this point that Eddie Eves and his brother Bedivere left the Surf Riders to form the Trio Samos with Rudy and Hugo’s cousin Bill Spemann. Malu Natapu also split and – accompanied by Bill Sevesi and friends – made the excellent 1963 LP Samoa – Authentic Sounds Authentic Songs for Viking.

By the time of Horst Stunzner’s involvement on the 1964 swan song ‘Let Me Hear You Whisper’, the Samoan Surf Riders sound had developed with some tracks taking on a more pronounced old-timey barbershop flavour.

The atypical ‘Mauga Ole Tatuolo’ is a song I rather like for its guitar style (redolent of Merle Travis) playing a cyclical riff that lodges in your brain just as tenaciously as the Samoan Surf Riders wonderfully evocative name.

The Samoan Surf Riders – ‘Mauga Ole Atuolo’ (1964)

Samoan Surf Riders – Let Me Hear You Whisper

Samoan Surf Riders – ‘Tosa Sua Oe’

Samoan Surf Riders – ‘Minoi Minoi’

Malu and the Samoan Planters – Samoa: Authentic Sounds Authentic Songs

The Korolevu Beach Serenaders – ‘Biau Mai’

Korolevu Beach Serenaders Present (Salem, 1973)

Playing sweet songs by a tropical lagoon as palms sway against the rising moon. It would seem to be the perfect gig, no?

Life as a musician in a resort or hotel band may not be as it first appears. If you’re from an out-in-the-sticks village with a tourist resort as your neighbour it’s probable that you, or other family members, will be in some way employed by that resort.

Hospitality requires a lot of grunt and before seeing to the guests’ evening hula dancing and fire-walks there’s a good deal of not so glamorous cleaning, cooking, bartending, gardening and maintenance to attend to. Hotshot ukulele player you may well be but there are still bills to pay, so needs, as they say, must.

By the time the bossa-tinged ‘Biau Mai’ was recorded and pressed to vinyl on the 1973 LP The Korolevu Beach Serenaders Present the band had already been around for more than 10 years. Maybe by then they’d achieved a level of fame that meant they were spared the grittier side of the tourist trade?

I hope so. They were great musicians with a splendid set-list of traditional Fijian songs, pop tunes, latin-esque curios like ‘Biau Mai’ and – that staple of the hotel band – risqué novelty numbers for tourists teetering on the edge of sunstroke and cocktail-primed for sauciness.

(Altogether now) “The higher the mountain the cooler the breeze/ E lei ka lei lei/ The younger the couple the tighter the squeeze/ E lei ka lei lei…”

While the album is presently not available to download or stream, the 1976 Ode LP The Korolevu Beach Serenaders Sing Songs From Around The Pacific is on Spotify.

The Adi Cakobau School Girls’ Choir – ‘Lia E’

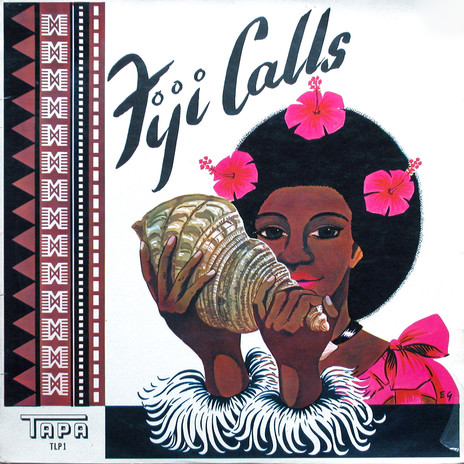

Fiji Calls (Viking/Tapa, 1961)

Hukarere Māori Club – ‘Hoea Mai Ngā Waka’

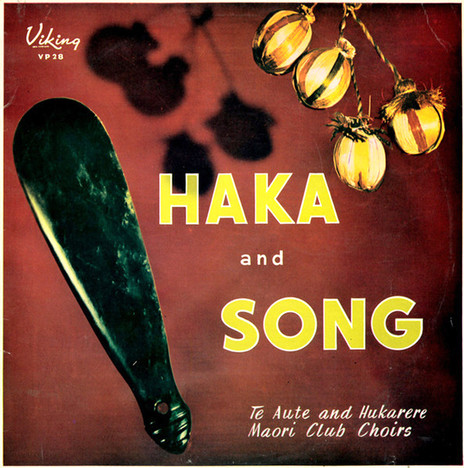

Te Aute and Hukarere Māori Club - Haka and Song (Viking, 1960)

The young girl who announces ‘Lia E’ would be into her late seventies by now. I wonder if she still remembers recording the song all those years ago?

The time her younger self imagined in Fiji, “before the white man”, was, by 1961, already 300 years gone. I suspect though that the point of her announcement was less to do with temporal accuracy and more of a (very) subtle reproach to the successive waves of interlopers with their depressingly familiar baggage of guns, alcohol, and disease.

But once the youthful voices of the Adi Cakobau Girls School start their ‘Meke’ chant they cast a spell so mesmeric that, for a few brief moments, you are transported to a place empty of men, white or otherwise, and – via the magic of magnetic tape – privy to the breath, thought and feeling of young women singing, outside of time, simply being themselves.

Along with those voices captured by the microphone on ‘Lia E’ there are chirping crickets and the suggestion of a sea breeze blowing through the classroom. Such accidental ambience is one of the pleasures of field recordings, sometimes even the point.

That’s not the case though with the sound of the Hukarere Māori Club, as recorded by Ivan Tidswell in 1960. On ‘Hoea Mai Ngā Waka’ the girls’ poi are purposefully placed in the mix-space usually allocated to percussion, creating a pillow-soft texture of the most delicate swirls and tap-tap-tapping over which their bright voices soar.

It’s such a gorgeous tune but unattributed on the record label (and all subsequent digital iterations) so its origins and authorship remain mysterious. It sounds early 20th century, European in its structure, but the Te Reo lyrics and exquisite poi work elevate it to something far more sophisticated than a translated hymn.

Like ‘Lia E’ the Hukarere Girls’ song has the power to transport, to carry the listener into a space where something hopeful can still be felt, and, by extension, possibly even achieved. In times as chaotic as these, we’d do well to take heed of the Hukarere Girls College’s motto: “Kia Ū Ki Te Pai – Cleave to that which is good”.

Availability: The Adi Cakobau Girls School Choir’s ‘Lia E’ is not available to stream or download, but their LP Voices of Fiji is on Spotify.

The Hukarere Girls’ ‘Hoea Mai Ngā Waka’ is on Spotify in great sound from the original tapes.

Will Crummer and the Royal Rarotongans – ‘Ko Koe Okotai Te Tumu’

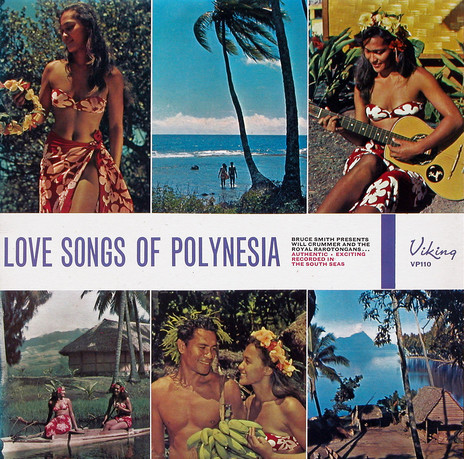

Will Crummer and the Royal Rarotongans - Love Songs of Polynesia (Viking, 1963)

Will Crummer’s first appearance on long-playing record was 1962’s Cook Island Magic. Accompanied by his “Sea Stars” the album sticks to a formula used by Viking on a number of its other Polynesian LPs: a mix of traditional drumming tracks, reinterpretations of older Island numbers and a few newly minted songs.

Standouts are the chugging down-home-jug-band sound of ‘Aiai’ and Will singing sweetly on ‘Uuna Koe’. There’s a little hesitancy in some of the performances, with arrangements occasionally rough around the edges, but all in all it’s a typical debut with young musicians accommodating a recording process that was less about artistic expression and more about the expedient turnover of usable takes.

What then, one wonders, happened between Cook Island Magic and the following year’s Love Songs Of Polynesia? I pose the question because from the very first notes of the song ‘Topiri’ on side one of the 1963 record the vibe is completely different; energy levels are immediately more intense and there’s a commitment only hinted at on the debut.

Prior to the recording sessions ukulele player Charlie Napa and lead guitarist Colin Tai were brought into Will’s group (now called the Royal Rarotongans). Napa’s briskly precise strumming style is very distinctive so it’s possible this additional texture helped invigorate proceedings. But Will is also singing with more purpose and confidence.

Two tracks in particular stand out.

‘Ko Koe Okotai Te Tumu’ and ‘Ine Ine’ had both been previously collated on the Cook Island field recordings of Harry Napa (released by Viking on the 1962 LP Moments In Rarotonga). Sonically the recordings on the compilation are primitive but these two songs – as performed for Napa by Teata Makirere – are superb.

‘Ine Ine’ is a little marvel of a tune, its melody dipping and descending when you expect it to rise yet its effect still wonderfully uplifting. Makirere’s voice has a poise and delicacy that’s quite special. Whatever happened to this guy?

But then you play the Royal Rarotongan’s version of ‘Ine Ine’ and straight away – with a call and response – Will is right there, the smoothness and power of his voice electrifying. The band are right there too, tight as tight can be, propelled by a pulsing pa’u drum.

As Will dips deep, Charlie Napa and a guitarist (Colin Tai? Takai Rahiti?) mesh in a tightly locked groove that is just utterly and relentlessly funky. It’s amazing, one of the great recordings of (checks notes again just to be absolutely sure) 1963! Who else, anywhere, was making music that sounded like this?

On ‘Ko Koe Okotai Te Tumu’ the Royal Rarotongans join Will in close vocal harmony and there’s a palpable sense of solidarity. While they play it’s possible to imagine Will Crummer as the navigator, guiding the band – his crew and their canoe – through the topography of the music.

The technical quality of his singing is a wonder – small inflections like the modulation of a note on the end of the line “Kiaku E Ine …” – but it’s never decorative or frivolous. Everything he does is purely in service to the song.

And as you’re listening you understand that Will’s knowledge of the music’s currents and lyrical tides is total. So much so that, with the song resolving, you relax, entranced by his craft and control, knowing now that the navigator with the ocean-deep voice is going to bring you safely through the reef, across the lagoon and all the way up to the beach without even getting your feet wet.

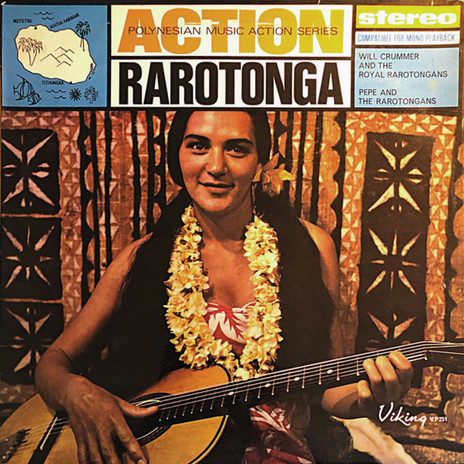

Will Crummer / Pepe and the Rarotongans - Action Rarotonga (Viking)

(Availability: The full LP, Love Songs of Polynesia is available to stream/download from Spotify but unfortunately the source tape has been processed with a horrible fake stereo effect. The best way to hear ‘Ine Ine’ is on the digital LP Action Rarotonga where it appears in great sound – albeit it with reverb, possibly added during tape copying in the late 60s – and is available from Spotify and Apple. The Harry Napa recordings released as Moments In Rarotonga are also available to stream and download.)

Love Songs of Polynesia

Action Rarotonga

Pepe and the Rarotongans – ‘Vas Mai Te Akau’/’E Tiare’ (‘Beyond The Reef’)

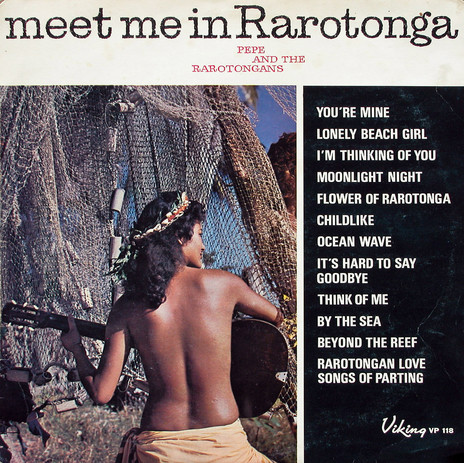

Pepe and The Rarotongans - Meet Me In Rarotonga (Viking, 1963)

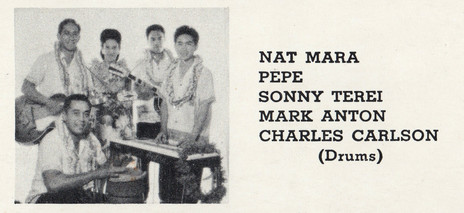

The story goes that Pepe got her first break when asked to step in and replace a no-show vocalist on one of (her husband) Sonny Terrei’s recording sessions.

I believe it: Pepe’s beguiling voice has an unaffected quality, not exactly amateur but almost as if you’re listening in at a private party. It’s the perfect fit for a track I’ve long obsessed over, the quietly sublime ‘Beyond The Reef’.

Written by Canadian-born Jack Pitman (who had been posted to Honolulu in 1943 to build US military infrastructure) the song was first recorded in 1949 by Napua Stevens for the Bell label of Hawaii.

Stevens was a charismatic young singer at Waikiki’s Moana Hotel and with her languorous voice and arresting beauty Pitman struck gold. Getting heavy airtime on the wildly popular radio programme Hawaii Calls – broadcast across the Pacific, Australasia, North America and, via armed forces radio, further into Europe and the Middle East – the record soon had sales of over 3.5 million copies.

In short order Bing Crosby and Alfred Apaka scored with the song too and Pitman’s success was sealed. Over the next few years he would write a string of big sellers in the Hapa Haole genre (Hawaiian-style songs written by non-native speakers) but never again turned out anything quite as good as ‘Beyond the Reef’.

For me the definitive recording remains the one by Napua Stevens. I’ve tried to find a cover that surpasses it but it’s a song she fully inhabits, conveying a core truth that possibly even Jack Pitman didn’t consciously intend.

(Whilst certainly not making fools of themselves, the big guns that had a crack at it – Bing Crosby, Elvis Presley, Andy Williams – crucially fail to grasp its starkly unsentimental bones. Emoting and trilling only obscures the songs fatalistic theme; also they’re men and the lyric’s mise en scène strikes me as a frame best suited for a female protagonist.)

Within the song’s first verse the narrator’s dread is revealed: “Beyond the reef/ Where the sea is dark and cold/ My love is far away/ and our dreams grow old”. Then comes her doubt – “Will he remember me/ Will he forget?” – and by the time she’s singing of flowers, cast to the trade winds (and by metaphorical extension being borne away on the ocean), the intimations are, indeed, worrying.

It’s the “dark and cold” line that always gets me though, for its fleeting glimpse of the void – a suggestion extremely rare in popular song of this period.

(You may think I’m reading too much into this, somehow implying that Pitman had been busy poring over his Carl Jung. He hadn’t, of course, but he was a smart guy – a Royal Academician and Browns scholar – and the song’s conception in the shadow of an unspeakably destructive war cannot be discounted in having shaped its symbolism.)

Pepe and the Rarotongans.

Of all the cover versions I’ve heard, only Pepe and the Rarotongans comes close to the original. Wisely the group match the song’s 1949 tempo, laying back to let Pepe carefully fashion each word, enunciating against their sparse instrumentation.

Does the fact that Pepe sings it in Cook Island Māori render my ramblings about the English lyric pointless? I don’t think so. In 1962 the song was the title of a big-selling New Zealand LP featuring Daphne Walker’s interpretation and her version is out there – on CD and streaming – so for comparison the English lyric is readily accessible.

But even if you come to Pepe’s cover with no prior knowledge of ‘Beyond The Reef’’ (and unable to speak te reo o te Kūki Āirani) it’s still possible to surrender to the songs distinctive mood and accept that music this sad and beautiful can be understood beyond any language.

Pepe and the Rarotongans – Meet Me in Rarotonga

Will Crummer – ‘Vas Mai Te Akau’ (renamed ‘E Tiare’)

Napua Stevens – ‘Beyond the Reef’, 1949

--